Reader's Choice

Blitz

By Brian Eggert |

Blitz feels like the natural outcome of Steve McQueen’s recent work. The writer-director’s five-film Small Axe series from 2020 about the Black experience in Britain and his four-hour documentary Occupied City (2023) about Amsterdam under Nazi rule feed into this account of London during the Blitzkrieg of 1940. The sweeping World War II drama also shares more than a few notes with Steven Spielberg’s 1987 adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun. Both follow a child separated from his parents through a harrowing and decidedly Dickensian wartime experience, narrowly surviving death while witnessing the most generous and darkest aspects of humanity in a series of episodic encounters. All the while, McQueen portrays an authentic, racially diverse London, not the whitewashed version that has been typical in so many war films about this era. He acknowledges that, despite other films portraying the Blitz as a time when London came together, bigotry remains even in the harshest of times. It’s a timely message, and it’s contained within an accomplished, if somewhat narratively slight film.

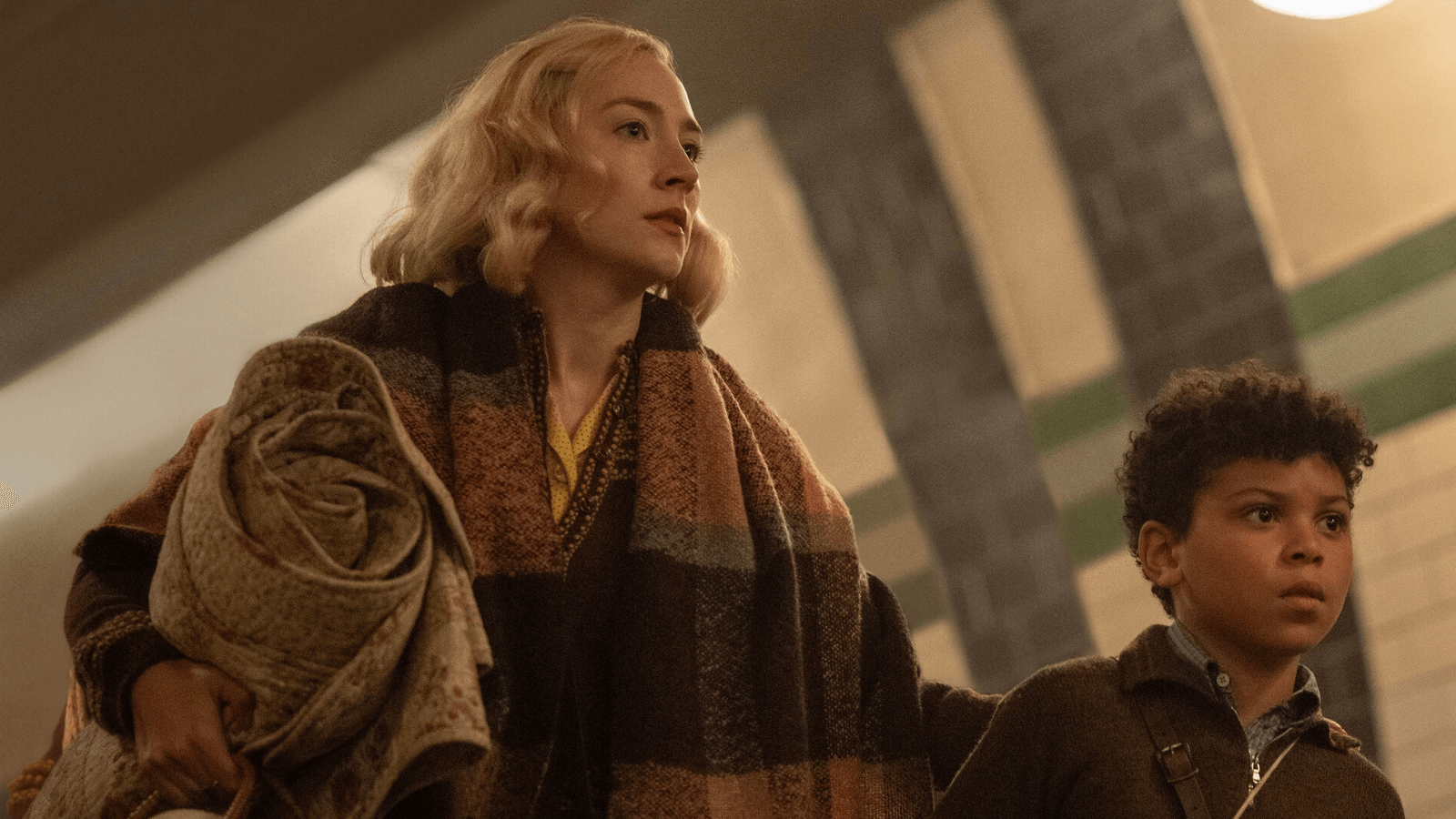

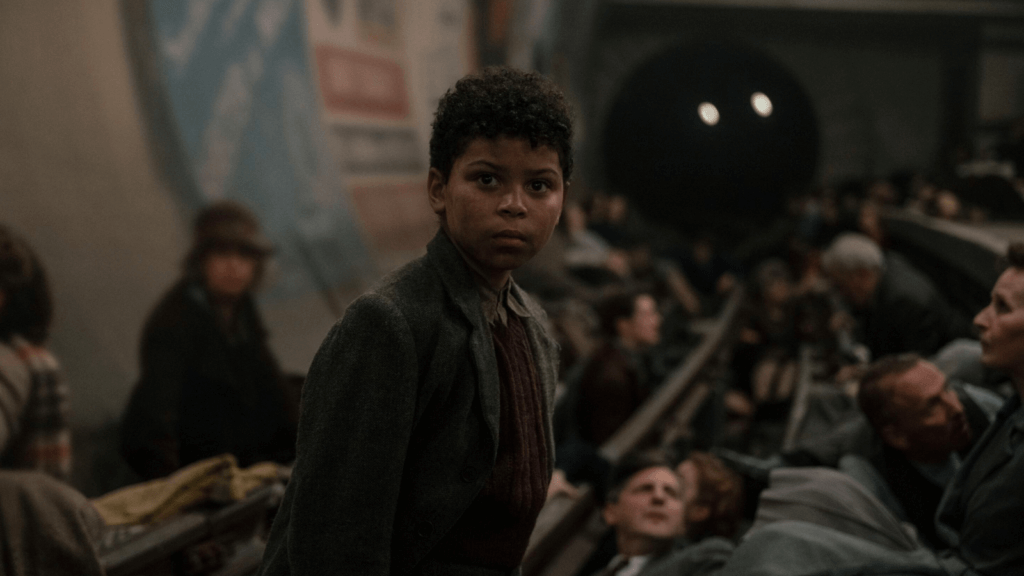

Blitz opens with titles establishing the historical context in September 1940. Then it settles on the 9-year-old George (Elliott Heffernan), whose single mother, Rita (Saoirse Ronan), arranges for him to be part of Operation Pied Piper—an effort to move over a million people, mostly children, out of London to keep them safe from the Nazi bombing raids. Bitter toward his mother for sending him away, George leaps off the train several miles outside London. The rest of the film charts his adventure back home. His encounters feel straight out of Oliver Twist; even his cat’s name is Ollie. On his journey, George encounters a trio of children his age who have the same idea of escaping. He also faces intolerant bullies but resolves they are “all talk and no trousers.” One night, a kindly Nigerian-born air raid warden helps George overcome his shame about being Black—the boy’s father, hailing from Granada, was deported after an encounter with racist police officers. But there’s also a crass Fagin-esque character, Albert (Stephen Graham), whose derangement and relationship with his coddling mother, Beryl (Kathy Burke), recall the mother-son dynamic in White Heat (1949). Albert forces George into a club full of fresh corpses in one disturbing scene that shows how apathetic and opportunistic people can be during wartime.

While mainly focused on George, Blitz also tracks Rita’s search for him, delving into her memories of George’s father and idyllic scenes at the piano with her father (Paul Weller, musician from The Jam and The Style Council). After learning the officials have lost track of her child, Rita joins an independent humanitarian movement to give people affected by the bombings a place to stay. It’s run by Mickey (Leigh Gill), who has been accused of being a communist for his willingness to help others. After citing biblical verse (“Do unto others as you would have others do unto you”), Mickey wonders if Jesus was a Red. After all, the British government has limited civilians’ access to the Underground, turning crowds of desperate people away to fend for themselves. Average Londoners, too, behave with cruelty toward people of color, regardless of whether they’re all targeted by the same Nazi threat. Part of George’s trek home involves realizing that British culture marginalizes Black people. McQueen beautifully captures George’s loss of innocence in a moment when a puppet show entertains a group of children, but he can no longer enjoy such childish things. He’s seen too much.

Still, Blitz struggles for air, as though McQueen and editor Peter Sciberras had been pressured to deliver a two-hour film. Produced in part by Apple Studios and given a limited theatrical release, followed by a home on the AppleTV+ app, the film may have suffered from pressure given the underwhelming box-office performance of the company’s longer-running productions from last year. By all accounts, Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon and Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, both long movies, failed to earn back their hefty budgets for Apple, and doubtlessly, the extended runtimes were blamed by those in charge. It’s worth speculating whether McQueen was bound by some limitation to his film’s length. At times, his choice to omit specific details feels like an intentional denial of information. One memorable cut goes from a dazzling, ritzy nightspot to a bird’s-eye view of a bomber and a resulting explosion seen from above the clouds, suggesting the club has been destroyed. It’s an elegant solution that doesn’t dwell on violence for entertainment value, as many war films do. Elsewhere, the editing feels rushed and dramatically curtailed, particularly in the final scene. Distractingly, McQueen achieves no meaningful closure for the family cat, while Harris Dickinson’s role as Rita’s potential love interest feels conspicuously trimmed.

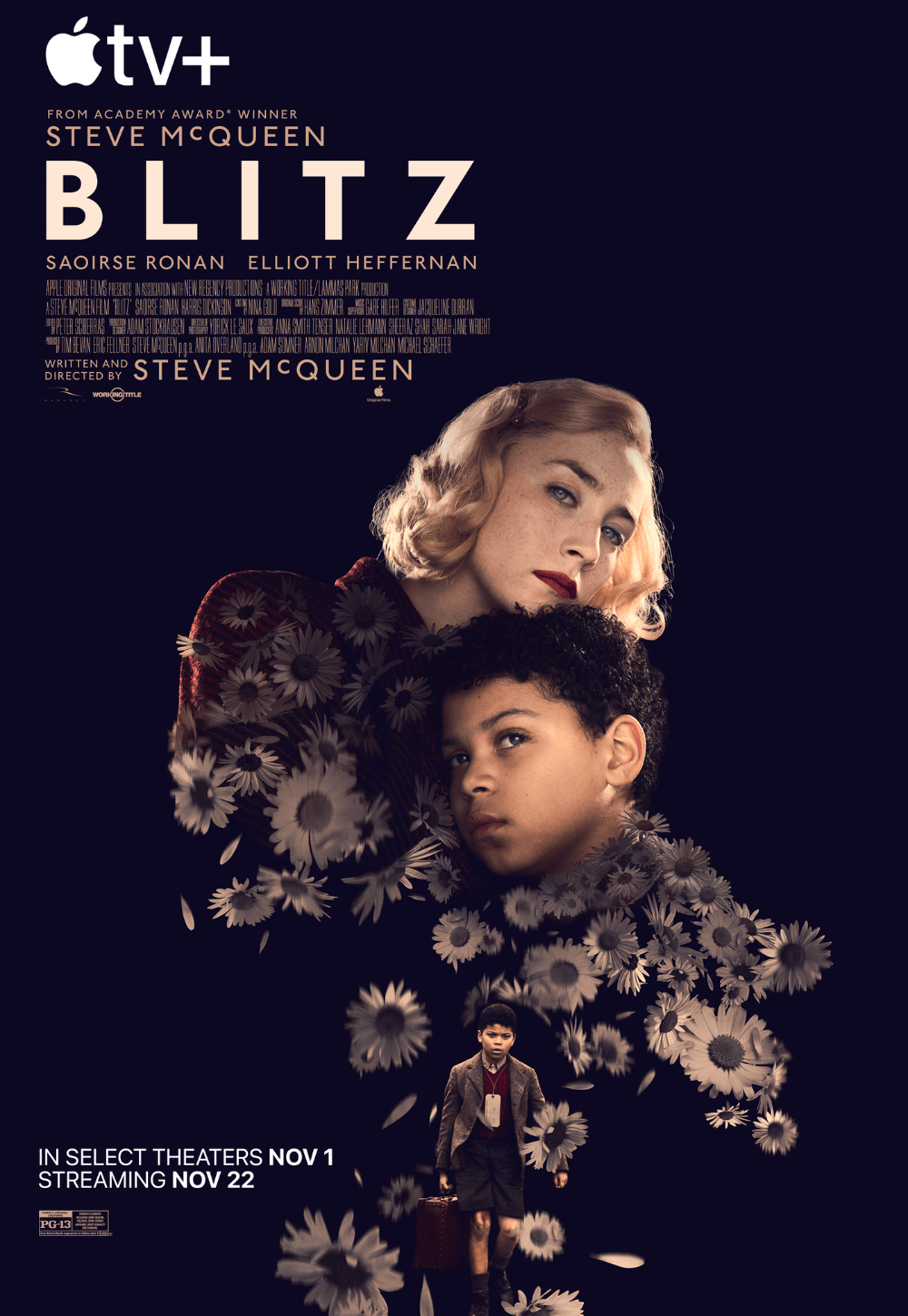

An experimenter at his core, McQueen approaches Blitz with sometimes abstract visual flourishes, far removed from the more classical depictions of this chapter in British history, such as John Boorman’s Hope and Glory (1987). McQueen and Yorick Le Saux, one of today’s best cinematographers, create evocative imagery that resists the usual visual tropes of World War II dramas. Blitz periodically shows a field of daisies in a shot that rattles and shakes until it blurs. George and his mother appear on the movie poster, covered in daisies like the May Queen from Midsommar (2019). Though McQueen never explicitly explains his flower imagery, it’s not difficult to extract some meaning about human fragility in a harsh world. Another sequence starts with the camera close to the water at night, racing at the speed of a bomber so fast that the up-close image resembles TV static. The shot pulls back to reveal airplane shadows on the dark surface, racing toward London. Yet, McQueen is not above large set pieces, such as a breathless flooding sequence set in the Tube or George’s narrow maneuvering in a massive fire.

In the end, Blitz is less about the equalizing effect of war than an honest look at the alternating selfishness and selflessness it brings out. The treatment recalls Spike Lee’s war film Miracle at St. Anna (2008), which reminds us that, even when fighting Nazis, racism was prevalent among American soldiers. McQueen’s storytelling is no less evocative for its familiarity, especially given its germane themes. Over-accented by a pointed string score from Hans Zimmer, Blitz has the occasional quality of a manipulative drama. This can feel at odds with the film’s deglamorized and unromantic portrait of wartime solidarity. McQueen seems to confront how past filmmakers have depicted such experiences in cinema, embracing how Dickens and Spielberg blend unfortunate realities with the dramatic need for a happy ending. In that sense, Blitz not only brings Empire of the Sun to mind but also channels Spielberg’s War of the Worlds (2005) in its focus on a single family during chaotic, world-changing events. McQueen brings a similar immediacy to his filmmaking, which gives way to a cinematic sentimentality; this may dilute Blitz’s impact or provide just the punctuation needed to move an audience to tears.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on November 12, 2024.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review