War of the Worlds

By Brian Eggert |

In Steven Spielberg’s science fiction, War of the Worlds remains something of an oddity. Its outlook on the prospect of human-alien interaction is bleak and stands as an antithesis to the director’s optimistic aliens in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, and even those alien-like robots at the end of A.I. Artificial Intelligence. And while it contains similar misgivings about technology as Spielberg’s Jurassic Park and Minority Report, it holds none of their purist fascination with the “science” of the story (aliens, heat-rays, and subterranean tripods are all very deadly). As a translation of H.G. Wells’ seminal alien invasion tale, the film moves the action from England to the United States and, while modernizing the source material, allows Spielberg to deliver a spectacle of alien destruction that, on the surface, sets aside his family-friendly label. But the adaptation maintains many of the original text’s most controvertible, arguably convenient flourishes so that, in spite of the film’s global cataclysm incited by world-conquering aliens, its epic scope remains centralized on a single family’s experiences during the takeover, and, therefore, it’s every bit as intimate as one would expect from Steven Spielberg.

Spielberg’s film follows the long tradition of Wells’ seminal book and its many adaptations by standing as a reflection of scientific, social, or political events germane to its place in history. With his book, Wells had anticipated the end of the Victorian era and the worst potential dangers in the coming century where science and technology would rule supreme. Later adaptations only solidified that notion. In 1938, as radio listeners tuned-in to hear the usual rumblings of war in Europe with Hitler’s rise, Orson Welles sent half of New England’s listeners running for the hills with his legendarily realistic radio broadcast. Later, producer George Pal and director Byron Haskin made an effects-laden spectacular in their 1953 adaptation, The War of the Worlds, a film that played on the Red Scare and hoped for divine intervention. And Spielberg’s 2005 film, written by David Koepp and Josh Friedman, channeled 9/11 and consciously incorporated parallels to the then-current Iraq War still fresh in viewers’ minds. When one of the characters sees destruction all around her, aliens don’t enter her mind; she immediately asks, “Is it the terrorists!?” Skies fill with clouds as robotic machines topple entire cities, but Spielberg finds poignant moments of humanity in familiar images—such as a father running with his daughter in his arms, both covered in ash—images not unfamiliar for those versed in 9/11 (or any catastrophe’s) news footage.

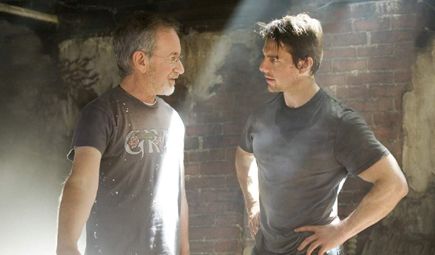

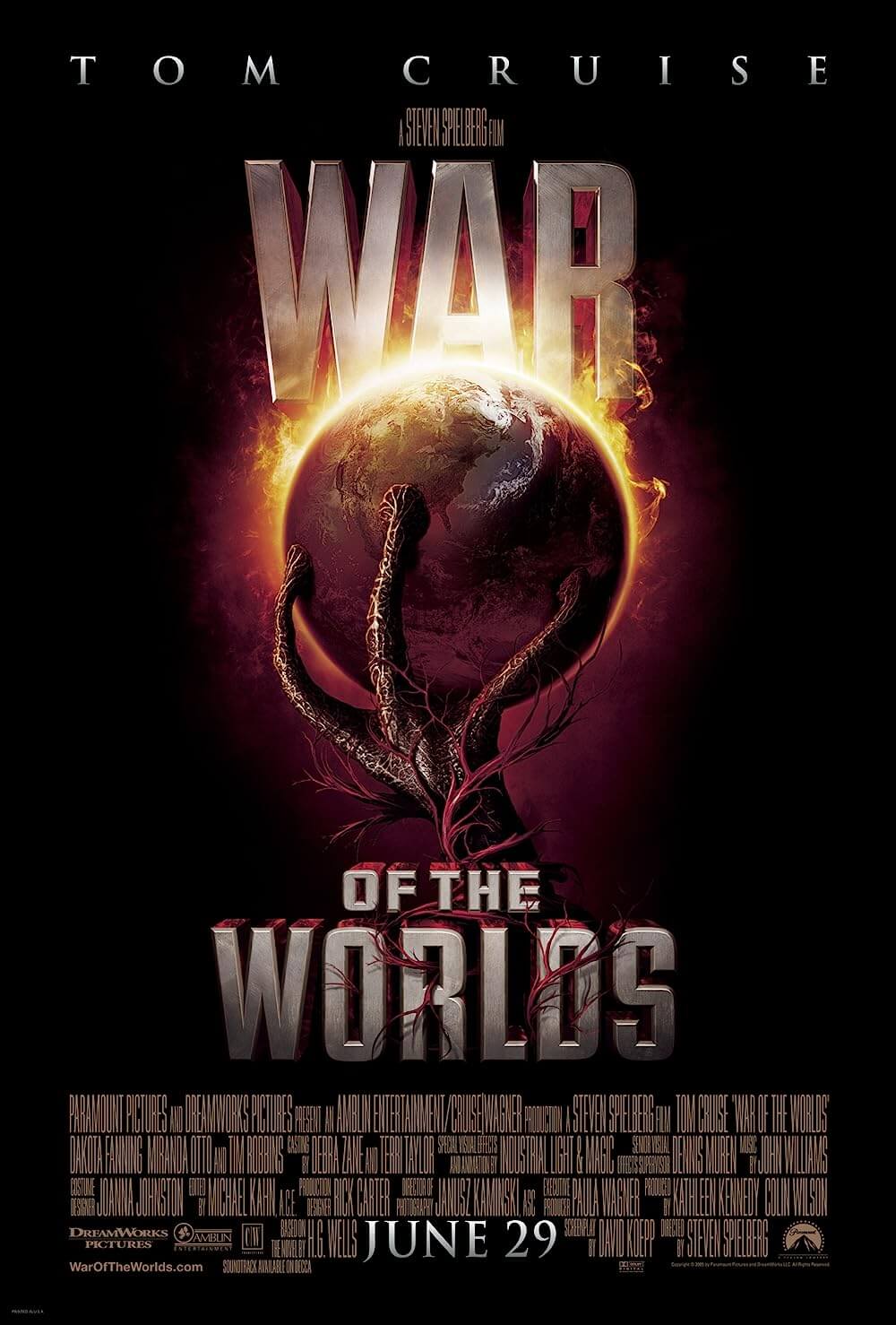

Its release was accompanied by a marketing campaign to match the larger-than-life collaboration between Hollywood’s most bankable director and its most popular star, Tom Cruise. The two had already worked together on Minority Report in 2002, but the global scale here was far more enormous. Millions were spent to produce and market the picture, and the posters showcased colossal letters that recalled the fonts from such past epics as Ben-Hur (1959) and King of Kings (1961). Six months before the film’s release, analysts predicted it would be the year’s biggest hit (it was fourth) and perhaps Spielberg’s largest earner—it’s certainly among his largest budgets. But just a few weeks before its Independence Day weekend opening on June 29, 2005, Cruise appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show, jumped for love on Oprah’s couch, and became something of a laughing stock in the public eye. His erratic behavior was vaguely attributed to his association with the unpopular Church of Scientology. Cruise’s promotional interviews centered on his newfound love with future ex-wife Katie Holmes, and the film itself was lost in the discussions. Some would argue that the public had grown weary of Cruise and, despite War of the Worlds’ stateside box-office take of $200 million, the film would have done better without the increasingly skewed perception of its star.

Its release was accompanied by a marketing campaign to match the larger-than-life collaboration between Hollywood’s most bankable director and its most popular star, Tom Cruise. The two had already worked together on Minority Report in 2002, but the global scale here was far more enormous. Millions were spent to produce and market the picture, and the posters showcased colossal letters that recalled the fonts from such past epics as Ben-Hur (1959) and King of Kings (1961). Six months before the film’s release, analysts predicted it would be the year’s biggest hit (it was fourth) and perhaps Spielberg’s largest earner—it’s certainly among his largest budgets. But just a few weeks before its Independence Day weekend opening on June 29, 2005, Cruise appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show, jumped for love on Oprah’s couch, and became something of a laughing stock in the public eye. His erratic behavior was vaguely attributed to his association with the unpopular Church of Scientology. Cruise’s promotional interviews centered on his newfound love with future ex-wife Katie Holmes, and the film itself was lost in the discussions. Some would argue that the public had grown weary of Cruise and, despite War of the Worlds’ stateside box-office take of $200 million, the film would have done better without the increasingly skewed perception of its star.

At any rate, critical responses were equally circumscribed and seldom passionate, their assessments lost in the special FX, visceral nature, and sheer size of the experience over the characters and their emotional underpinnings, which is, oddly enough, what makes War of the Worlds far more lasting than any version before it. Andrew Sarris argued, “Overall, the film is too lacking in feeling to provide a recognizably human experience.” On the flipside, other critics expected a film of broader worldly scope as the title implies and felt the spectacle was lost in the entrenched humanity. Referring to the way the film avoids a typical blockbuster formula and does not require its heroes to save the day, the critic in The New York Post wrote, “This disappointing War of the Worlds limps to a conclusion that mercifully ensures there will not be a sequel.” Indeed, the film’s sci-fi logic and large-scale exhibition were less Spielberg’s concern next to his desire to create a familiar, iconographic atmosphere that the audience could not ignore on an emotional level. After all, Roland Emmerich had already made a worldwide alien invasion movie with Independence Day (1996), a film about blowing up monuments the world over. Spielberg’s film reminds us that amid the global horrors are personal stories about individuals.

Perhaps Morgan Freeman’s off-screen bookend narration feels somewhat misplaced here, then. His voice of authority suggests something big is on the horizon. It opens the film and tells us aliens have watched our planet with envy and made plans, and at the end explains how the invading race is wiped out by ordinary microscopic Earth organisms to which humans are immune. In between Freeman’s grand observations, New Jersey divorcé Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise, in his most natural of performances) takes his rebellious son Robbie (Justin Chatwin) and anxious daughter Rachel (Dakota Fanning, excellent) from his ex-wife (Miranda Otto) for the weekend, and his rocky parent-child interactions continue even after an unearthly storm looms overhead. Near his disheveled bachelor pad, lightning strikes the same spot again and again, and suddenly all electricity from batteries to city power goes out, killed by an electromagnetic pulse. All at once, there’s a rumbling from under the city street surface at the lightning’s point of impact, and then the ground caves in, and from inside emerges a tripod—a three-legged robotic machine armed with heat-rays that reduce its victims to ash. Rattled, unequipped as a parent, and unsure what to do, Ray gathers his children, who take no comfort from their unnerved-but-trying father. Ray finds the last working automobile in his neighborhood and, with children in tow, sets out to find his ex. But crossing a displaced countryside wrought with tripod attacks, an airliner crash, geared-up military forces, and panicky masses primes Ray into a protective father mode.

Perhaps Morgan Freeman’s off-screen bookend narration feels somewhat misplaced here, then. His voice of authority suggests something big is on the horizon. It opens the film and tells us aliens have watched our planet with envy and made plans, and at the end explains how the invading race is wiped out by ordinary microscopic Earth organisms to which humans are immune. In between Freeman’s grand observations, New Jersey divorcé Ray Ferrier (Tom Cruise, in his most natural of performances) takes his rebellious son Robbie (Justin Chatwin) and anxious daughter Rachel (Dakota Fanning, excellent) from his ex-wife (Miranda Otto) for the weekend, and his rocky parent-child interactions continue even after an unearthly storm looms overhead. Near his disheveled bachelor pad, lightning strikes the same spot again and again, and suddenly all electricity from batteries to city power goes out, killed by an electromagnetic pulse. All at once, there’s a rumbling from under the city street surface at the lightning’s point of impact, and then the ground caves in, and from inside emerges a tripod—a three-legged robotic machine armed with heat-rays that reduce its victims to ash. Rattled, unequipped as a parent, and unsure what to do, Ray gathers his children, who take no comfort from their unnerved-but-trying father. Ray finds the last working automobile in his neighborhood and, with children in tow, sets out to find his ex. But crossing a displaced countryside wrought with tripod attacks, an airliner crash, geared-up military forces, and panicky masses primes Ray into a protective father mode.

Along with Cruise’s damaged public profile in 2005, the film’s minor plot holes led to an underestimation of War of the Worlds. Even today, those searching for sci-fi logic in a film about a family’s survival question why a bystander is spotted recording the tripod on his digital camcorder after the aliens’ electromagnetic pulse zapped all electronics (but then, as viewers, we only assume the electromagnetic pulse; there is no scientist or resident expert in the film to explain what’s going on—we have to feel our way through it). Other debatably inconsequential plot holes occur, making it so the film may not stand up to microscopically close inspection, but such analyses overlook the sheer energy with which Spielberg has assembled his production—another driving force behind War of the Worlds. In that regard, the film has much in common with Jurassic Park, whereby captivating human characters run from a towering, deathly force, all delivered with great cinematic bravado. And within this nonstop scenario, Spielberg orchestrates moments of pure filmmaking that remain spectacular upon repeated viewings. Consider the deceptively simple sequence where Ray and his children navigate through stalled traffic in a minivan. Cinematographer Janusz Kaminski’s camera movements bob and weave passed stopped cars and hordes of stranded drivers, the frame whooshing in and out of the van thanks to CGI, circulating around what in another filmmaker’s hands might’ve been a dull sequence filmed entirely inside a car. Beyond moments where Spielberg echoes 9/11 imagery, he also makes incredible use of the tripods’ imposing stature. They tower over crowds or move through cities with vast, slow steps that implant them in the viewer’s memory as iconographic cinema—shots best described as epic and ambitious.

But War of the Worlds is at its best when Spielberg breaks the massive scope to explore themes of family amid the frightened mob mentality prevalent throughout the film. There’s a microcosmic sequence where Tim Robbins appears as a paranoid survivalist named Harlan who makes deranged plans for a rebellion in the cellar of an old farmhouse, the scene serving as a metaphor for the entire picture. Harlan’s behavior incites Ray to blossom into a full-fledged protector after they narrowly avoid the alien equivalent to a fiberscope, and then an alien survey team. Ray is forced to fight and kill Harlan in fear that his loud ranting will alert the aliens. Cruise is excellent in these scenes and delivers a complete growth of character in his performance, emphasizing the film’s overarching theme of human bonding during and after a massive catastrophe (reflecting post-9/11 patriotism). Moreover, Cruise’s role is uncommon in Spielberg’s filmography, in that the director’s films usually concern families or children with absent father figures. Here, as in Minority Report, Cruise represents a deeply flawed father who, through the course of the film, restores some shattered levels of balance to his family. Even after Robbie seemingly dies in a wave of fire when he abandons Ray and Rachel to fight aliens with the U.S. Army, the film reunites Robbie in what some consider an all-too-convenient conclusion. Then again, this plot detail is drawn directly from Wells, who reunited the book’s narrator-protagonist with his presumed-dead wife by the last pages.

But War of the Worlds is at its best when Spielberg breaks the massive scope to explore themes of family amid the frightened mob mentality prevalent throughout the film. There’s a microcosmic sequence where Tim Robbins appears as a paranoid survivalist named Harlan who makes deranged plans for a rebellion in the cellar of an old farmhouse, the scene serving as a metaphor for the entire picture. Harlan’s behavior incites Ray to blossom into a full-fledged protector after they narrowly avoid the alien equivalent to a fiberscope, and then an alien survey team. Ray is forced to fight and kill Harlan in fear that his loud ranting will alert the aliens. Cruise is excellent in these scenes and delivers a complete growth of character in his performance, emphasizing the film’s overarching theme of human bonding during and after a massive catastrophe (reflecting post-9/11 patriotism). Moreover, Cruise’s role is uncommon in Spielberg’s filmography, in that the director’s films usually concern families or children with absent father figures. Here, as in Minority Report, Cruise represents a deeply flawed father who, through the course of the film, restores some shattered levels of balance to his family. Even after Robbie seemingly dies in a wave of fire when he abandons Ray and Rachel to fight aliens with the U.S. Army, the film reunites Robbie in what some consider an all-too-convenient conclusion. Then again, this plot detail is drawn directly from Wells, who reunited the book’s narrator-protagonist with his presumed-dead wife by the last pages.

American audiences accustomed to blockbusters of mass destruction in 2005 felt War of the Worlds was a letdown and wasn’t the crowd-pleasing, popcorn-munching, no-brainer that Independence Day was. Then again, it’s worth noting that the critics at France’s Cahiers du cinéma, usually ahead of the curve, put the film on their top ten list for the year—a curious choice for any film that’s just another blockbuster. Of course, no Spielberg film operates on one level alone, and this film is certainly no exception. Had the film’s marketing campaign not suggested another kind of film (of Roland Emmerich ilk) and focused instead on the deeply human struggle at its center, War of the Worlds may have been perceived differently. But Spielberg avoids grotesque cutaways to Paris burning, Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer toppling over, or the White House exploding; his imagery is more affecting and invariably human, and his focus on a single family amid a worldwide conflict would inspire the narrative structures of later blockbusters such as World War Z and 2014’s Godzilla. Highly influential, ever innovative, and full of emotion and slick formal trickery, the film lives up to the precise definition of what “Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds” should be.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review