The Running Man

By Brian Eggert |

Among the countless movie dystopias, few feel more plausible than the one portrayed in The Running Man. It’s a far cry from the scorched post-apocalyptic wasteland of the Mad Max series. The world-building feels more natural and less contingent on the far-fetched global infertility crisis in Children of Men (2006). The scenario resists the fanciful, storybook-like future of robotics and cityscapes in A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). And there’s no inkling of H.G. Wells’ symbolism in The Time Machine (1960, 2002), where the working class turns into subterranean underdwellers; however, given the recent trend of billionaire bunkers, the super-rich may become the Morlocks of our future. In any case, Edgar Wright’s new version of The Running Man presents a chilling reflection of today’s extreme socioeconomic divide, so much so that watching the movie, it registers less as science fiction and more as a future that’s not all that different from today. The rich are richer, the poor are poorer, but one thing hasn’t changed: those with wealth and power continue to exploit those without it.

Wright and co-writer Michael Bacall (Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, 2010) adapt Stephen King’s 1982 book The Running Man, originally credited to his edgier pen name, Richard Bachman. The story involves a twisted game show, where desperate contestants could earn a fortune by surviving for 30 days, while the participating public scrambles to earn a hefty reward by ousting its players to the show’s lethal hunters. Although adapted for the screen once before in 1987, with Arnold Schwarzenegger starring in a splashy, cartoonish action movie that retained little of the book’s nihilism or commentary, the new version closely follows the original text. Of course, the filmmakers cannot help but wink at the earlier version. Schwarzenegger appears on the future’s bill for one hundred “new bucks,” and a few details from the earlier movie, such as a sled drop into the game, are replicated here. But mostly, it’s a faithful translation of King’s book, thrillingly so.

Glen Powell stars as Ben Richards, a blue-collar stiff with a wife, Sheila (Jayme Lawson), and a sickly baby they cannot afford to treat. Ben has been blacklisted by the corporation—referred to as the “Network”—that seems to own everything, including the U.S. government, preventing him from getting work. These early scenes of Ben’s domestic situation couldn’t be more timely or resonant, with The Running Man debuting as Republicans plan to remove healthcare benefits from millions of Americans and raise premiums for millions more to astronomical, unrealistic degrees. Desperate, Ben resolves to subject himself to one of the many exploitative shows run by the Network, hoping to become a contestant on a lower-risk show to earn a few hundred bucks to save his child. However, his short temper and history of losing dangerous jobs for insubordination make him the perfect candidate for the titular show (the intake rep calls him “the angriest man ever to apply to our shows”). It’s the Network’s most popular chunk of propaganda from which no one survives. But even if Ben lasts just a week, he could secure a payday for his just-surviving wife and child that would set them up for life.

The show is a spectacle of death televised on the government’s free propaganda station—its name, taken from the book, is a homonym for the streaming service Freevee. Hosted by the flashy Bobby T (Colman Domingo, a delight), the game sets its three players loose with just 12 hours to run and hide before the hunt. Unlike the 1987 version, there’s no gameshow arena; the whole country becomes a colosseum for what the Network’s cap-toothed exec, Dan Killian (Josh Brolin), describes as modern-day gladiatorial games. There’s no talk of alliances between Ben and his fellow players, the reckless Laughlin (Katy O’Brian) and hilariously dopey Jansky (Martin Herlihy), all of whom must periodically record and submit supposedly untraceable video updates for the show. After their initial half-day grace period, the chase begins. The game show’s hunters, led by the masked McCone (Lee Pace)—“Who fight for real freedom,” says Bobby T, in one of his many American exceptionalist maxims—rely on viewer feedback to locate the runners. To encourage viewer participation, the show offers a financial reward to the largely impoverished population if they inform on the runners, meaning anyone and everyone could be a threat.

It doesn’t take long for Ben to discover the Network is playing a rigged game for maximum viewership, compliance, and control. He learns from some helpers in the underground—William H. Macy’s fake ID and weapons dealer, Daniel Ezra’s online conspiracy theorist, and Michael Cera’s justly paranoid revolutionary—that Killian and company have manipulated every aspect of their show, the outcome included. Those untraceable tapes? They’re trackable. Worse still, “DNA sniffers” on street lamps can detect anyone, anywhere. Floating “rover cams” capture the action for the home viewers. Deep fakes control the narrative. And Christian casinos keep the masses poor and dependent on the government and media. All of this means Ben remains cornered and fueled by anger, determined to burn down the Network. Powell commits to the part, portraying a volatile but sympathetic hothead whose presence is merely two-dimensional, but it’s the kind of blunt-force hero this material requires. My only complaint is that Powell should probably hit the gym more often. (I jest. His shirtless scenes made me want to put down my box of Milk Duds, but I didn’t.)

As the title suggests, The Running Man is a movie of chases and places, racing from one action set piece to another with a frenzied speed that left me exhausted after the 133-minute runtime. The paranoid, surveillance-logged world recalls that of Minority Report (2002) at times, with cameras and advertising everywhere (Liquid Death, anyone?), along with an infrastructure designed to close in on any dissenter. Wright, who’s no stranger to hyper-stylized action, orchestrates dazzling sequences, including a breathless chase in a veteran apartment complex and another inside a booby-trapped house that puts Kevin McCallister’s efforts to shame. Editor Paul Machliss sometimes resorts to overly quick editing to convey chaos, but the action is mostly cohesive and clear. Between the sharp cinematography by Chung-hoon Chung—who shot Wright’s last film, Last Night in Soho (2021), as well as several Park Chan-wook features—and the superb VFX that convincingly realize this Orwellian future throughout, Wright delivers a movie that could be watched as a pure adrenaline rush. Its remarks on the class divide only enrich its sheer entertainment value.

As for The Running Man’s place in Wright’s filmography, it doesn’t reach the heights of his Cornetto Trilogy—Shaun of the Dead (2004), Hot Fuzz (2007), and The World’s End (2011)—but it’s a testament to the bravura showmanship the filmmaker can bring to established material. I preferred this to his last couple of features. Wright and Bacall adhere closely to the book’s plot, with a few understandable deviations along the way. For instance, they reconsider King’s fatalistic original ending, because, I assume, they rightly predicted it would play in poor taste to post-9/11 audiences. Instead, they devise a galvanizing alternative that relies less on King’s characteristic Bachman cynicism and more on fulfilling Ben’s promise as “The Initiator”—a revolutionary force that incites people to recognize how they’ve been exploited and to fight back. While I prefer King’s ending for its absolutism, the one conceived for this $100 million Hollywood production is no less radical. It’s rare to see commercial cinema taking such a firebrand stance, as opposed to the usual offend-no-one mode of blockbuster movies.

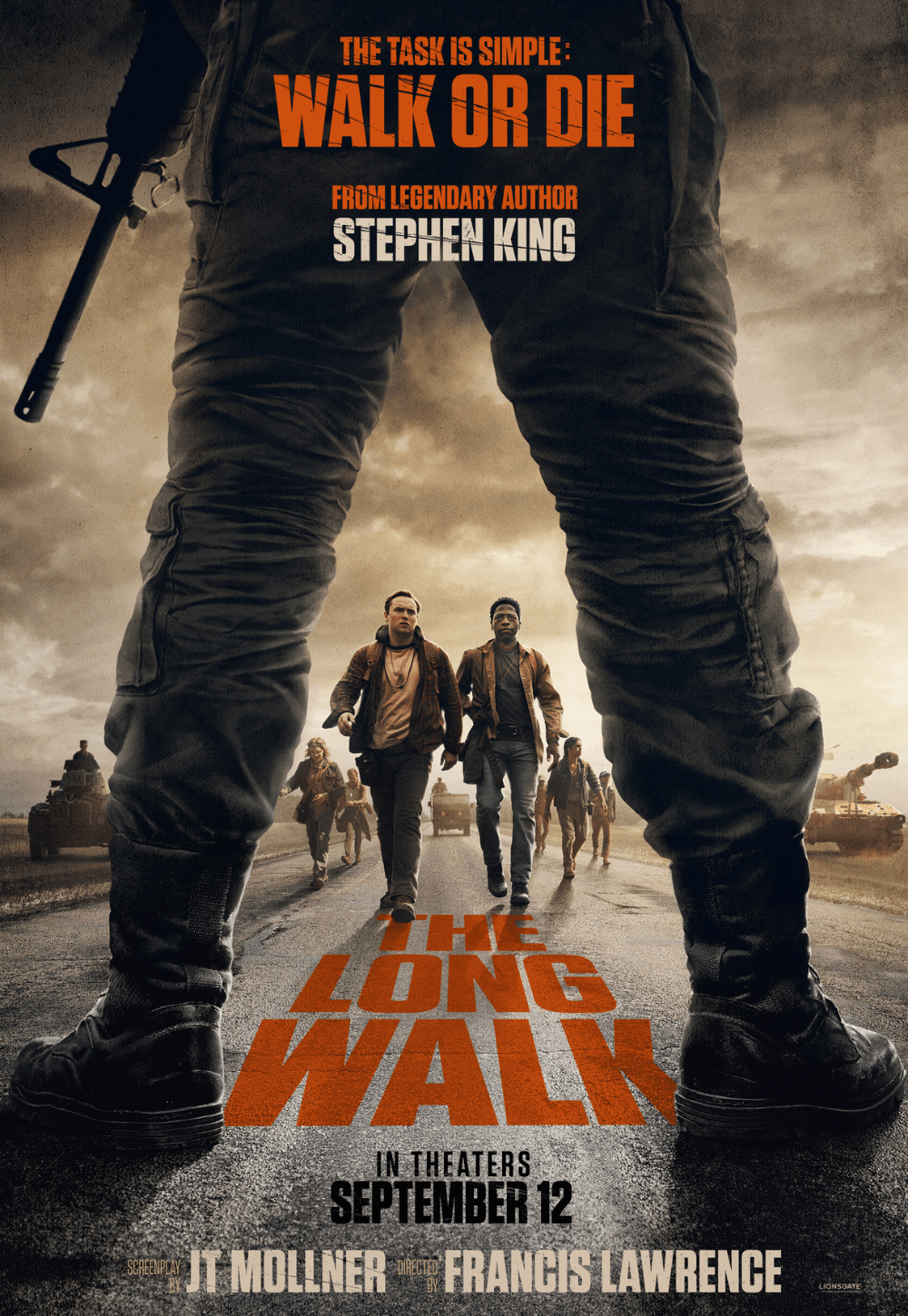

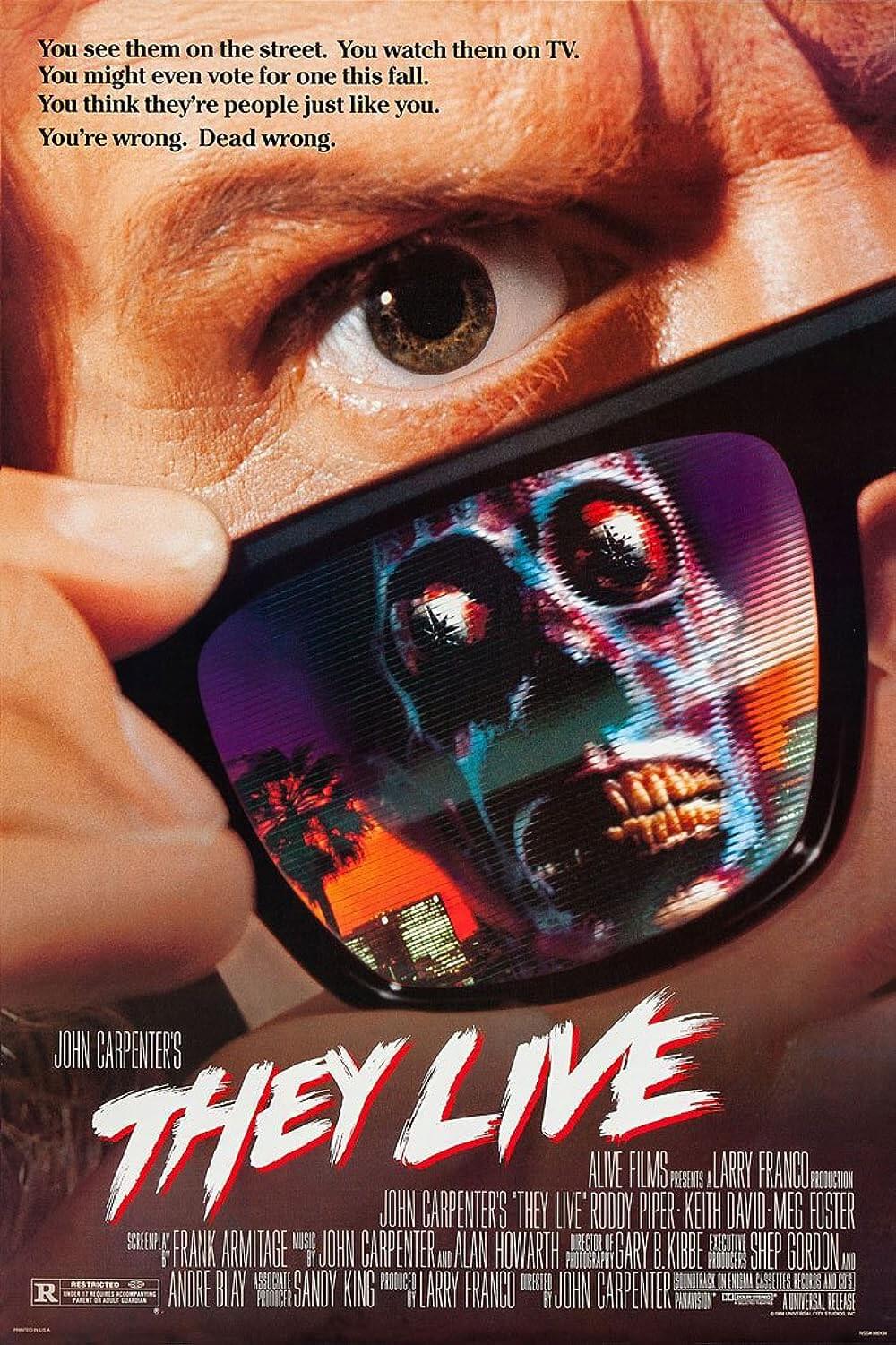

Of course, there have been many movies about game shows or entertainment as propaganda, from Battle Royale (2000) to the excellent Hunger Games series, which boasts comparable ideas. For the best of them, look no further than this year’s The Long Walk, a similarly themed King adaptation about a government that employs a merciless spectacle to turn its people into willing participants in their own oppression. And while The Long Walk is a superior, albeit far bleaker film, The Running Man imparts an almost identical message in a more accessible package. This is an angry film. Not since John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) has there been such a brutal yet exciting look at how the powerful exploit the masses.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review