The Definitives

They Live

Essay by Brian Eggert |

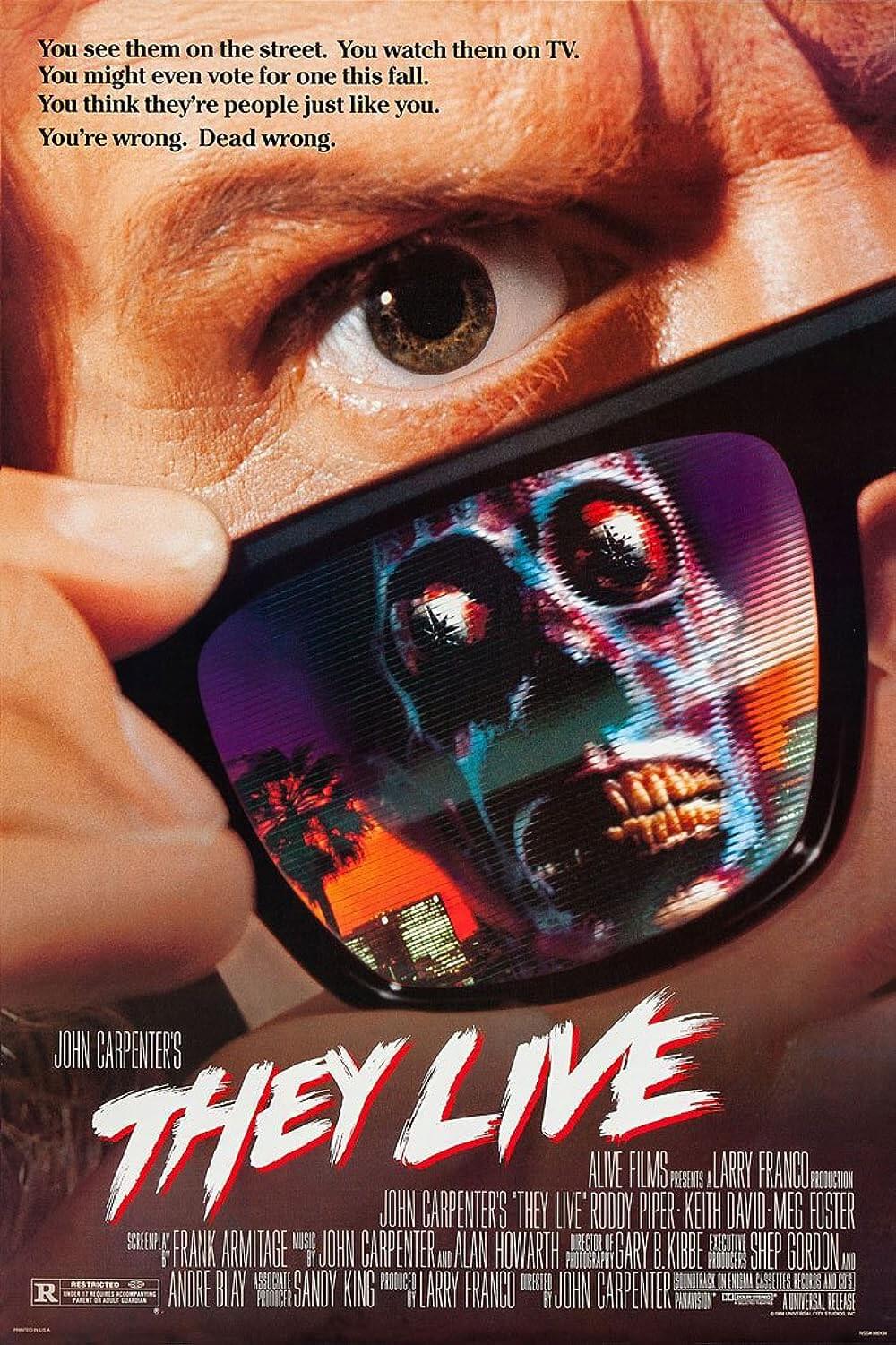

“It figures it would be somethin’ like this,” says the hero of John Carpenter’s They Live. Nada, a homeless man named after the Spanish word for “nothing,” has just discovered an alien conspiracy. When he looks through special sunglasses, he sees in black-and-white that a ruling class of alien politicians, entertainers, and super-rich have subjugated American society, turning the sleeping middle-class into a culture of enslaved consumer drones. In part a rousing act of filmic rebellion against Reagan-era and capitalist ideologies, in part a pastiche of classic science-fiction and Western tropes, They Live is pure Carpenter and a quintessential cult classic. The title alone suggests an Us versus Them theme for the viewer, creating an association that links our alien overlords with a class of capitalists, politicians, mass media institutions, and popular culture—and by association, strengthens the countercultural ambitions of the film. Indeed, They Live contains all the requisite traits of a cult classic, beginning with its overriding sense of defiance, directed in large part toward systems of authority. But then, the film’s cultisms extend to the film’s cheesy dialogue; excessive violence; grisly alien flesh that looks like a skinned human; inter-dimensional travel; classic genre film nostalgia; omnipresent B-movie badness; and a seven-and-a-half-minute street fight, complete with body slams and a piledriver. And lest we forget, the presence of pro-wrestler Roddy Piper.

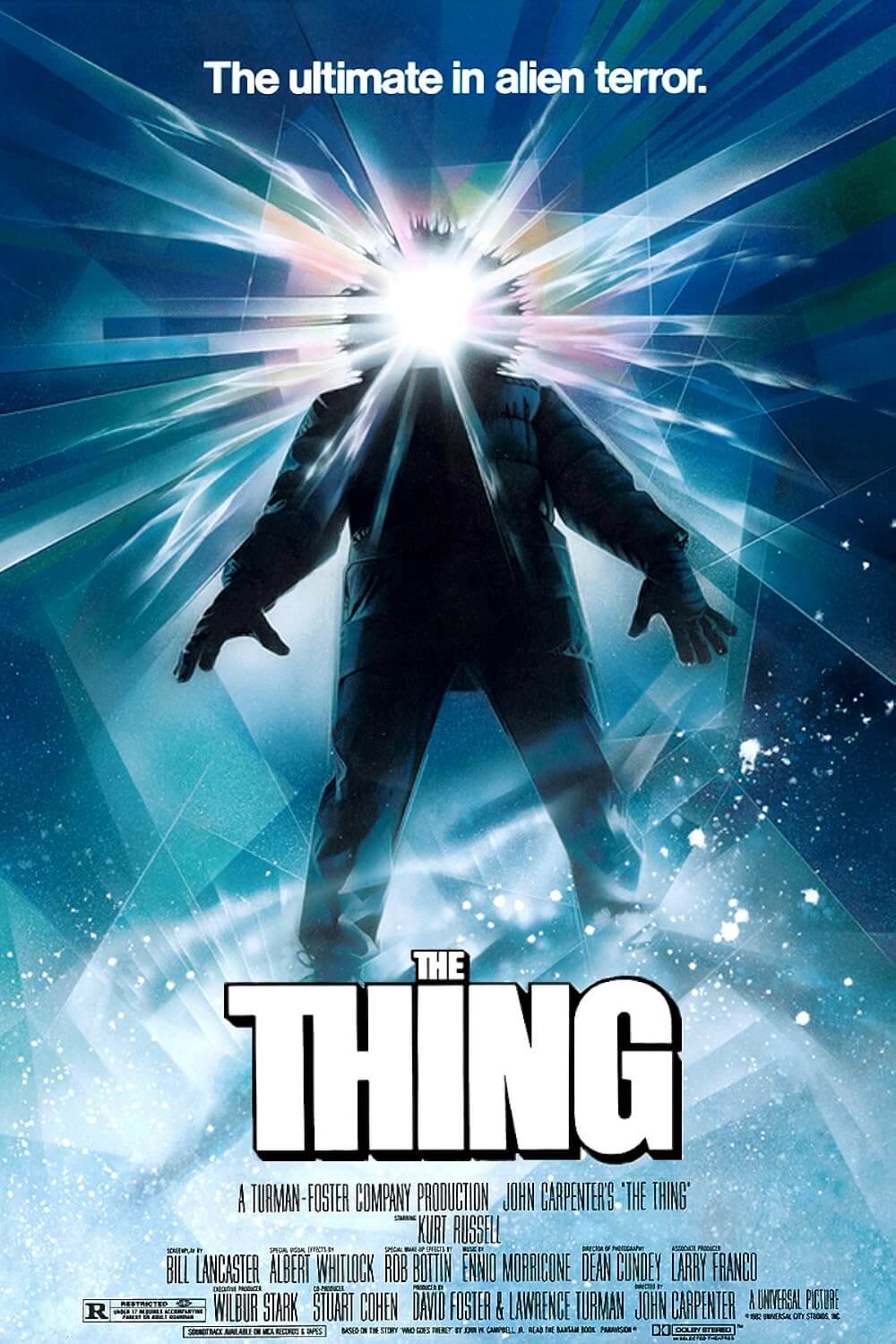

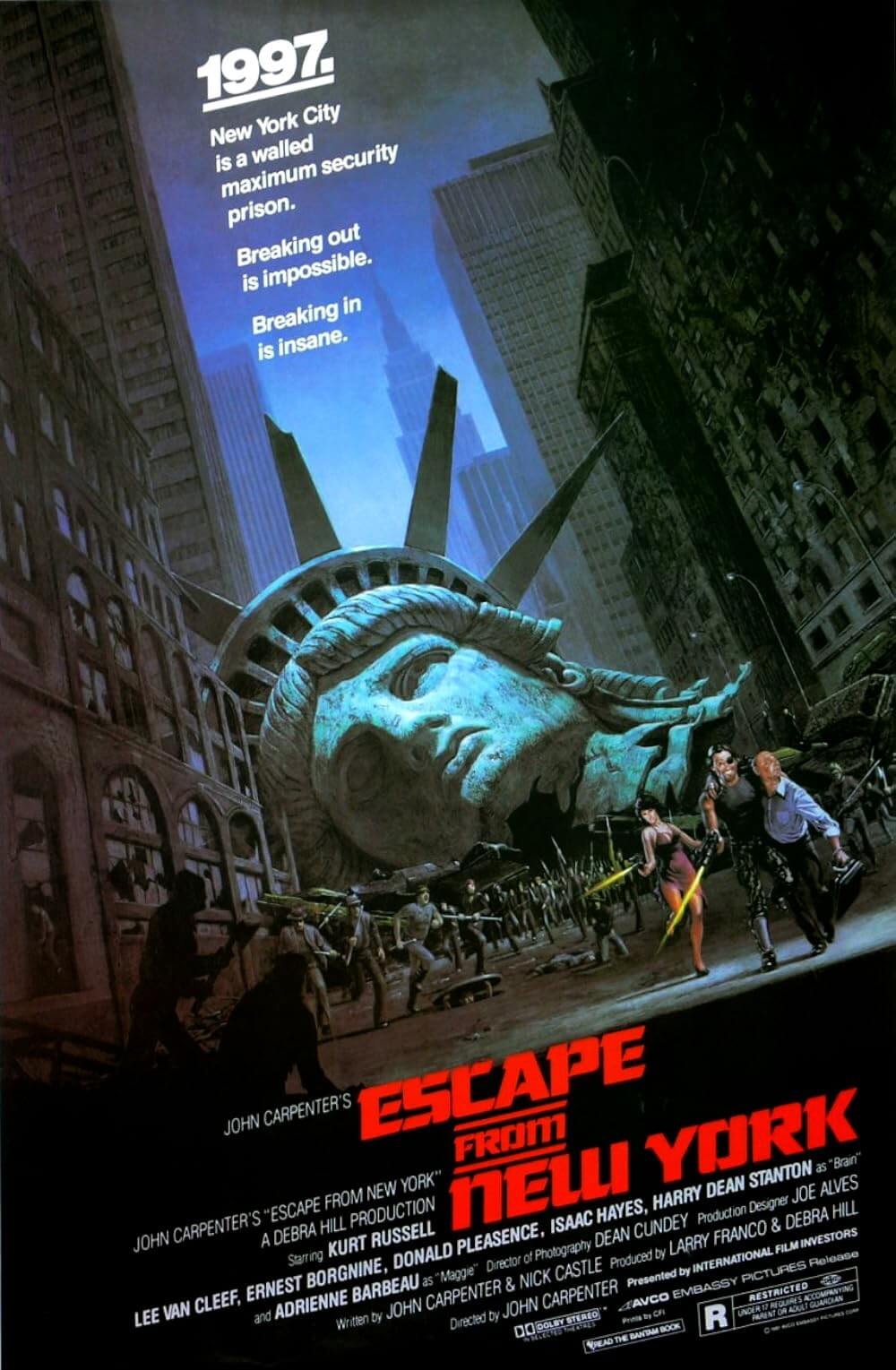

A film brimming with outrage, They Live could only come from a distinct, auteurist voice. John Carpenter often serves as producer, writer, editor, and composer of his films—most of which are preceded by “John Carpenter’s,” a rare distinction granted to just a few filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock. How fitting, as his sensibilities draw from classical modes of filmmaking. He maintains a penchant for monster movies, the Westerns of Howard Hawks, classic science-fiction like It Came from Outer Space (1953), and the horror writings of H.P. Lovecraft—material from which Carpenter seems to have drawn his themes and film grammar, committing him to the world of cult filmmaking. Having learned the trade at University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts in the late 1960s, Carpenter soon dropped out to make short films—he won an Academy Award for Best Live-Action Short for his 1970 film The Resurrection of Broncho Billy—and his first feature, Dark Star (1974). Carpenter went on to direct other cult classics such as Halloween (1979), The Fog (1980), Escape from New York (1981), The Thing (1982), Big Trouble in Little China (1986), and In the Mouth of Madness (1994). But no film more than They Live captures his blend of cult aesthetics, classic Hollywood influence, and sheer rage against the American Way of the 1980s.

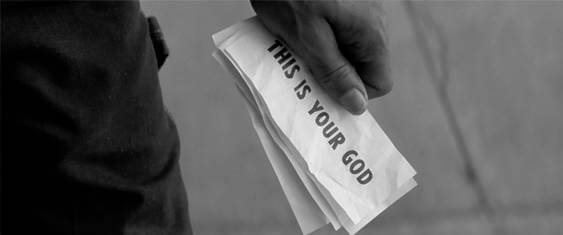

Set to Carpenter’s blues theme composed alongside Alan Howarth, the deliberately paced opening finds Nada wandering into Los Angeles in search for work. After striking out at the unemployment office, he gets an off-the-books job at a construction site, where he befriends Frank (Keith David), a fellow homeless man. They take shelter at a shantytown community called Justiceville, where Nada notices a group conspiring in a nearby church, talking about trying to break through signals on TV. Soon enough, police come with bulldozers to wipe out Justiceville, beating and arresting many of its inhabitants. Although Nada escapes, he returns to investigate the church and finds a pair of sunglasses made by the Justiceville conspirators. When Nada puts on the sunglasses, he sees in black-and-white. The glasses reveal the real world all around him: He looks at ads and billboards through the glasses and sees subliminal messages like OBEY, MARRY AND REPRODUCE, STAY ASLEEP, and CONSUME. At the same time, when he looks at well-to-do people, he sees aliens in disguise—aliens who control everything. He snaps, arms himself, and announces his rebellion: “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass. And I’m all out of bubblegum.”

Set to Carpenter’s blues theme composed alongside Alan Howarth, the deliberately paced opening finds Nada wandering into Los Angeles in search for work. After striking out at the unemployment office, he gets an off-the-books job at a construction site, where he befriends Frank (Keith David), a fellow homeless man. They take shelter at a shantytown community called Justiceville, where Nada notices a group conspiring in a nearby church, talking about trying to break through signals on TV. Soon enough, police come with bulldozers to wipe out Justiceville, beating and arresting many of its inhabitants. Although Nada escapes, he returns to investigate the church and finds a pair of sunglasses made by the Justiceville conspirators. When Nada puts on the sunglasses, he sees in black-and-white. The glasses reveal the real world all around him: He looks at ads and billboards through the glasses and sees subliminal messages like OBEY, MARRY AND REPRODUCE, STAY ASLEEP, and CONSUME. At the same time, when he looks at well-to-do people, he sees aliens in disguise—aliens who control everything. He snaps, arms himself, and announces his rebellion: “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass. And I’m all out of bubblegum.”

Not long after identifying Nada as “one that can see,” the aliens try to convert him to their cause, promising fame and fortune in exchange for complicity. He rebuffs their offer and escapes by kidnapping a cable TV executive named Holly (Meg Foster). While trying to convince her of an alien conspiracy, she eventually thumps him on the head and frees herself. Alone again, Nada seeks out Frank for help. After a brutal alleyway fistfight, Nada convinces Frank to try on the glasses. Frank sees what Nada sees—aliens, everywhere—so they join an underground rebellion, led by a Justiceville organizer (Peter Jason). To Nada’s surprise, Holly shows up at a rebellion meeting. Just then, the aliens raid the meeting. Only Nada and Frank escape the raid, using alien tech that transports them to the alien underground—a place they explore courtesy of a guided tour by a bum-turned-social-elite (George “Buck” Flowers). Seeing an advanced network of tunnels, inter-dimensional transporters, and media control, Nada and Frank learn the aliens are actually the super-rich and powerful, and many people sell-out to help them without much fuss. Nada and Frank launch an affront raid on the cable TV station and destroy the satellite dish emitting the signal that hides the aliens. Though Nada and Frank die in the process, betrayed by Holly, they stop the alien signal. Every concealed message and alien is now visible to everyone.

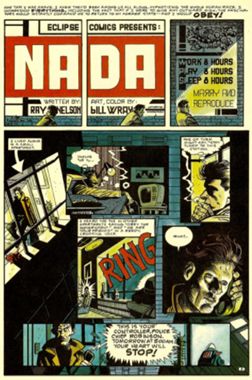

Carpenter was inspired to make They Live after reading “Nada,” an eight-page story in Eclipse Comics’ Alien Encounters, based on Ray Nelson’s short story “Eight O’Clock in the Morning,” originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in the 1960s. “Nada” spoke to Carpenter’s disgust over the commercialist culture and selfishness of the Reagan political regime, so he purchased the rights to both the short story and the comic book. Alive Films, an independent production company designed to give Carpenter creative carte blanche and final cut, as long as the film was completed within its narrow budgetary constraints of just over $3 million, handled the production. Universal Studios handled the distribution. He credited his screenplay to the name “Frank Armitage,” a reference to H.P. Lovecraft’s 1928 short story “The Dunwich Horror,” about a scientist who fights against a hidden force controlling the world. Nevertheless, the studio was unconvinced with Carpenter’s draft. A Universal executive questioned why the aliens were not, say, turning poor people into food as in Soylent Green (1973). When Carpenter explained that he wanted the aliens to be after “our business,” the executive replied “Where’s the threat in that! We all sell out every day.” Carpenter used that very line in the film, maintaining the integrity of his vision and capitalist critique.

Carpenter was inspired to make They Live after reading “Nada,” an eight-page story in Eclipse Comics’ Alien Encounters, based on Ray Nelson’s short story “Eight O’Clock in the Morning,” originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in the 1960s. “Nada” spoke to Carpenter’s disgust over the commercialist culture and selfishness of the Reagan political regime, so he purchased the rights to both the short story and the comic book. Alive Films, an independent production company designed to give Carpenter creative carte blanche and final cut, as long as the film was completed within its narrow budgetary constraints of just over $3 million, handled the production. Universal Studios handled the distribution. He credited his screenplay to the name “Frank Armitage,” a reference to H.P. Lovecraft’s 1928 short story “The Dunwich Horror,” about a scientist who fights against a hidden force controlling the world. Nevertheless, the studio was unconvinced with Carpenter’s draft. A Universal executive questioned why the aliens were not, say, turning poor people into food as in Soylent Green (1973). When Carpenter explained that he wanted the aliens to be after “our business,” the executive replied “Where’s the threat in that! We all sell out every day.” Carpenter used that very line in the film, maintaining the integrity of his vision and capitalist critique.

They Live’s greatest claims to its cult status reside in its transgressive nature, how it undermines authority in the political, social, and cultural realms. While still in production, Carpenter described the film as a “wake-up call” in a 1988 interview with Starlog magazine, citing the corruption and greed of the Regan presidency as his launchpad. He later told interviewer Gilles Boulenger, “I got fed up with being told over and over again that it was so beneficial to be a consumer. We are no longer producing anything in the United States. We are just consuming and eating our way through… It was just starting to outrage me.” A shrinking middle-class, racial injustice, and widespread homelessness prevailed in the 1980s, signaled by voodoo economics that kept the upper echelon rich, as well as the emergence of a drone-like MTV viewing culture. At a 2015 repertory screening, Carpenter told the audience, “A lot of the ideals that I grew up with were under assault, and something called a yuppie came into existence, and they just wanted money. And so by the late ’80s, I’d had enough, and I decided I had to make a statement.”

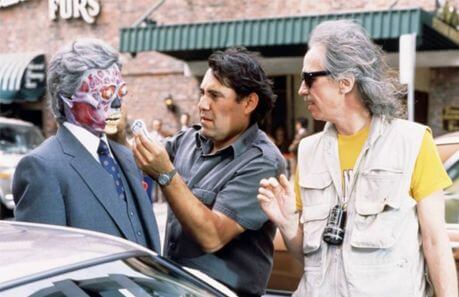

The shoot lasted eight weeks between March and April of 1988, filming on location in and around downtown Los Angeles, in areas where Carpenter had lived years earlier. The homelessness had only gotten worse in the interim. Knowing he had a limited budget, Carpenter wrote for fewer locations and focused on making a cheaper film. Sandy King, Carpenter’s wife, designed the look of the aliens; meanwhile, the director also convinced the film’s fight choreographer, Jeff Imada, to double as most of the aliens in a cost-cutting measure. Cinematographer Gary B. Kibbe, who shot most of Carpenter’s mid-to-late career efforts, used color film stock rather than more expensive black-and-white celluloid, and then he drained the color to create the appearance of monochrome—even so, Los Angeles’ smog-ridden sky provided a grim backdrop in the otherwise colorful world. And despite shooting an alien invasion film in downtown L.A., Carpenter remarked that passers-by seemed unconcerned about the alien subliminal messaging on a magazine stand set: “People who didn’t see the cameras walked by on the street. They literally paid no attention when the covers said ‘OBEY.’ They looked for a moment, and moved right on. We had a big sign on a building which said ‘CONFORM.’ People glanced up at it, and didn’t give it a second thought. It was hard to believe.”

The shoot lasted eight weeks between March and April of 1988, filming on location in and around downtown Los Angeles, in areas where Carpenter had lived years earlier. The homelessness had only gotten worse in the interim. Knowing he had a limited budget, Carpenter wrote for fewer locations and focused on making a cheaper film. Sandy King, Carpenter’s wife, designed the look of the aliens; meanwhile, the director also convinced the film’s fight choreographer, Jeff Imada, to double as most of the aliens in a cost-cutting measure. Cinematographer Gary B. Kibbe, who shot most of Carpenter’s mid-to-late career efforts, used color film stock rather than more expensive black-and-white celluloid, and then he drained the color to create the appearance of monochrome—even so, Los Angeles’ smog-ridden sky provided a grim backdrop in the otherwise colorful world. And despite shooting an alien invasion film in downtown L.A., Carpenter remarked that passers-by seemed unconcerned about the alien subliminal messaging on a magazine stand set: “People who didn’t see the cameras walked by on the street. They literally paid no attention when the covers said ‘OBEY.’ They looked for a moment, and moved right on. We had a big sign on a building which said ‘CONFORM.’ People glanced up at it, and didn’t give it a second thought. It was hard to believe.”

Most critics censured the film and cited its cheap-looking quality and thematic obviousness. Richard Harrington of the Washington Post called the material “so old it ought to be carbon-dated… You don’t have to get deep down to realize [Carpenter] hasn’t a clue what do with [his commentary], or the talent to bring it to life”. Indeed, many critical appraisals noted aspects of the film’s production; Janet Maslin of The New York Times cites its “B-movie bluntness.” The film was favored more in the pages of genre and cult fandom magazines, such as Cinefantastique, whose critic called it “A consummate, oddly exciting vision of Orwellian thought control.” The film topped two weeks of slow box-office performance, earning $13 million over its $3 million budget; but then, as actor Keith David noted, “It must’ve pissed someone off,” because it strangely disappeared from theaters altogether. Timed to release just before Election Day in 1988, They Live left people to wonder if George H.W. Bush or his running mate Dan Quayle were aliens. After all, the film’s themes and rumored suppression cannot help but raise the viewer’s suspicions about their government, a seemingly vital notion for any film to achieve cult classic status.

Along with cultishness comes an inherent level of badness, which They Live remains aware of and seems to celebrate. For instance, the unapologetic quality of the makeup proves laughable at times, especially in color, where it’s apparent that the alien colors of red and blue have been merely painted on an actor’s skin. Though in black-and-white the aliens, with their silvery orb-shaped eyes, look striking, we may nonetheless wonder how they articulate with their lack of lips and a mouth that moves like an actor wearing a rubber mask à la The Planet of the Apes (1968)—because that’s exactly how the effect was achieved. By the same token, the film’s plot also has a touch of badness: Its plot holes reflect a decidedly American exceptionalist take, suggesting that a single satellite dish atop a U.S. cable network could somehow brainwash the entire planet. For instance, were people in India affected by this takeover, and if so, will the destruction of a single satellite dish somehow ensure their liberation? Did the aliens, who have inter-dimensional transportation technology, not have the foresight to put a backup plan in place? Perhaps most absurd is the ending—that delightfully trashy last shot of a couple having sex, when the woman on top realizes for the first time that her significant other is an alien. “What’s the matter, baby?” he says, in a shameless moment.

Along with cultishness comes an inherent level of badness, which They Live remains aware of and seems to celebrate. For instance, the unapologetic quality of the makeup proves laughable at times, especially in color, where it’s apparent that the alien colors of red and blue have been merely painted on an actor’s skin. Though in black-and-white the aliens, with their silvery orb-shaped eyes, look striking, we may nonetheless wonder how they articulate with their lack of lips and a mouth that moves like an actor wearing a rubber mask à la The Planet of the Apes (1968)—because that’s exactly how the effect was achieved. By the same token, the film’s plot also has a touch of badness: Its plot holes reflect a decidedly American exceptionalist take, suggesting that a single satellite dish atop a U.S. cable network could somehow brainwash the entire planet. For instance, were people in India affected by this takeover, and if so, will the destruction of a single satellite dish somehow ensure their liberation? Did the aliens, who have inter-dimensional transportation technology, not have the foresight to put a backup plan in place? Perhaps most absurd is the ending—that delightfully trashy last shot of a couple having sex, when the woman on top realizes for the first time that her significant other is an alien. “What’s the matter, baby?” he says, in a shameless moment.

They Live’s leading man and his ability to carry out the famous alleyway fight sequence represent an alternative form of badness altogether. Carpenter designed the extended fight as an “ode to professional wrestling,” modeling the confrontation on the one between John Wayne and Victor McLaglen in John Ford’s 1952 picture The Quiet Man. Pro-wrestling achieved a cult status among adolescent boys and boyish adults in the 1980s. Roderick Toombs, best known as “Rowdy” Roddy Piper (1954-2015), served as a pro-wrestler in the WWF, coming to prominence in the 1980s alongside other icons of the cult sport, such as Andre the Giant, Hulk Hogan, Randy “the Macho Man” Savage, and King Kong Bundy. Along with “Rowdy” Roddy Piper’s experience as a pro-wrestler, David had a boxing background, which meant fight choreographer Jeff Imada could arrange a fight that looked incredibly real, despite its laughable length and use of pile drivers. But rather than just seven-and-a-half-minutes of two men beating on each other—a winking concept in itself—the sequence has a story. It follows Nada trying to convince Frank to believe him, saying things like “Either put on these glasses, or start eatin’ that trash can.” Frank tries to mind his own business, “Not this year.” Nada’s eventual victory turns the fight sequence into more than just violence, but a point-of-no-return in the larger narrative—Nada has convinced someone to believe him.

Nada is another in a long line of the director’s working-class heroes, such as the blue-collar scientists in The Thing or trucker Jack Burton in Big Trouble in Little China. Piper gives a low-key performance at first, as when Nada expresses his hope for America, saying, “I deliver a hard day’s work for my money. I just want the chance. It’ll come. I believe in America. I follow the rules. Everybody’s got their own hard times these days.” His optimism lasts until aliens show up. Then he goes into wrestling mode. His appeal as a film hero is without question. But regardless of Piper’s time as a homeless person and undoubtable connection to Nada, Carpenter was unaware of that when he cast the wrestler-turned-actor; rather, Carpenter met Piper at WrestleMania III and appreciated his everyman quality. Piper’s appeal, and much of the film’s, marks a cult phenomenon for the same reasons outlandish violence and over-the-top behavior make professional wrestling a cult phenomenon. (Ironically, wrestling’s popularity at the time maintained a gross, hyperbolic view of the body, an attitude that rewarded big hair and the bulging muscles of Rambo and Arnold Schwarzenegger—Piper had them both with his mullet and burly physique. Then again, Piper’s presence in They Live is hardly as contrary as, say, Brat Pitt’s presence in Fight Club.)

Nada is another in a long line of the director’s working-class heroes, such as the blue-collar scientists in The Thing or trucker Jack Burton in Big Trouble in Little China. Piper gives a low-key performance at first, as when Nada expresses his hope for America, saying, “I deliver a hard day’s work for my money. I just want the chance. It’ll come. I believe in America. I follow the rules. Everybody’s got their own hard times these days.” His optimism lasts until aliens show up. Then he goes into wrestling mode. His appeal as a film hero is without question. But regardless of Piper’s time as a homeless person and undoubtable connection to Nada, Carpenter was unaware of that when he cast the wrestler-turned-actor; rather, Carpenter met Piper at WrestleMania III and appreciated his everyman quality. Piper’s appeal, and much of the film’s, marks a cult phenomenon for the same reasons outlandish violence and over-the-top behavior make professional wrestling a cult phenomenon. (Ironically, wrestling’s popularity at the time maintained a gross, hyperbolic view of the body, an attitude that rewarded big hair and the bulging muscles of Rambo and Arnold Schwarzenegger—Piper had them both with his mullet and burly physique. Then again, Piper’s presence in They Live is hardly as contrary as, say, Brat Pitt’s presence in Fight Club.)

However cultish They Live may appear, the film has a classical Hollywood style, such as Carpenter’s frequent use of medium and master shots that isolate characters in their world. Carpenter isn’t interested in new tech here; he’s interested in throwbacks, whether they reflect the modern world or simply gratify his affection for Golden Age cinema. Consider his nods to the Western alone. Nada occupies the Western trope of the outsider who moseys into town, discovers something very off, and then tries to set things right—a theme found in films like My Darling Clementine (1946) and Shane (1953). Similarly, a scene where Nada stands in the church doorway mirrors a shot from John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) in which John Wayne looks outside from the darkened interior. As with many Carpenter films, the director also borrows a Hawksian trope, consecrated in Rio Bravo (1958), in which men band together against a superior force. A similar theme prevails in Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, and Ghosts of Mars (2000). And while Nada’s name recalls Clint Eastwood’s “Man with No Name” in Sergio Leone’s trilogy, Carpenter borrows more from classical Western influences, as opposed to the ironic sensibilities of Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns.

Alongside They Live’s classical Western influences, Carpenter draws from science-fiction of the 1950s. His use of black-and-white harkens back to the era of filmmaking to which Carpenter pays homage, resulting in a film that, in its colorless scenes, appears very much like a classic sci-fi yarn (most of the film’s visual effects, such as the black-and-white billboards, were achieved with old-fashioned techniques such as matte paintings and stop-motion sequences). Classical science-fiction tropes found alien intruders promising liberation through slavery. Films such as It Came from Outer Space, Invaders from Mars (1953), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, 1978), and Village of the Damned (1960, which Carpenter remade in 1995) contain aliens that take over the minds of human beings and promise a better world through their control and the human race’s subservience. Aliens from the fifties were symbols for Communist intruders who threatened America’s sense of personal freedom and free enterprise capitalism that had come to define the country’s values.

Alongside They Live’s classical Western influences, Carpenter draws from science-fiction of the 1950s. His use of black-and-white harkens back to the era of filmmaking to which Carpenter pays homage, resulting in a film that, in its colorless scenes, appears very much like a classic sci-fi yarn (most of the film’s visual effects, such as the black-and-white billboards, were achieved with old-fashioned techniques such as matte paintings and stop-motion sequences). Classical science-fiction tropes found alien intruders promising liberation through slavery. Films such as It Came from Outer Space, Invaders from Mars (1953), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956, 1978), and Village of the Damned (1960, which Carpenter remade in 1995) contain aliens that take over the minds of human beings and promise a better world through their control and the human race’s subservience. Aliens from the fifties were symbols for Communist intruders who threatened America’s sense of personal freedom and free enterprise capitalism that had come to define the country’s values.

Meanwhile, many of those so-called Communist intruders were simply blacklisted and scapegoated Americans with an alternative point of view, many of them ousted by friends or colleagues to groups like the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). They Live considers the worst enemy not the aliens who have pulled the veil over our eyes, but collaborators in the “Human Power Elite” who sell out the human race for a piece of the “better life.” The Justiceville drifter played by Flowers willingly joins the aliens and, during his not-very-thoughtful guided tour of alien headquarters for Nada and Frank, argues his side: “It’s business, that’s all it is. What’s wrong with having it good for a change? You can have a little taste of that good life too. Now, I know you want it. Hell, everybody does… We all sell out every day. Might as well be on the winning team.” The worst of them is Holly, who goes back-and-forth between the rebels and aliens, using hints of seduction and deception to infiltrate the rebels and expose them. The only thing worse than waking up to an alien invasion is realizing your fellow human being was helping you stay asleep. At this, Carpenter seems to offer his response through Frank earlier in the film, “Maybe they’ve always been with us… Maybe they love it… seeing us hate each other, watching us kill each other off, feeding on our own cold fucking hearts.”

To be sure, They Live remains emblematic of a countercultural rebellion—hence the name of Nada’s “Hoffman lenses” suggesting an influence from either Albert Hoffman, the Swiss chemist and discoverer of LSD, or Abbie Hoffman, the anarchist and social rebel. Nada even describes the experience of wearing Hoffman lenses “like a drug.” After taking that drug, he sees clear beyond the veil. In reality, that veil represents what philosopher Louis Althusser called an Ideological State Apparatus—an institution such as the mass media, which reinforces capitalist ideologies and secures ideological rule “through repression.” The overriding power of these Apparatuses manufactures consent among the “sleeping middle class,” as a rebel scientist call them. Take how most people in They Live just want to improve their lives with riches. The film features television commercials attesting to their desire to be a TV celebrity because, “I never grow old, and I never die.” The film’s other faux commercials advertise ornately long nails, new cars, and “divine excess” in all forms. “We are their cattle. We are being bred for slavery,” the scientist proclaims. Carpenter saw around him a self-obsessed consumer culture addicted to escape—an America that seemed to get its values and culture from television, and he sought to rebel against it.

To be sure, They Live remains emblematic of a countercultural rebellion—hence the name of Nada’s “Hoffman lenses” suggesting an influence from either Albert Hoffman, the Swiss chemist and discoverer of LSD, or Abbie Hoffman, the anarchist and social rebel. Nada even describes the experience of wearing Hoffman lenses “like a drug.” After taking that drug, he sees clear beyond the veil. In reality, that veil represents what philosopher Louis Althusser called an Ideological State Apparatus—an institution such as the mass media, which reinforces capitalist ideologies and secures ideological rule “through repression.” The overriding power of these Apparatuses manufactures consent among the “sleeping middle class,” as a rebel scientist call them. Take how most people in They Live just want to improve their lives with riches. The film features television commercials attesting to their desire to be a TV celebrity because, “I never grow old, and I never die.” The film’s other faux commercials advertise ornately long nails, new cars, and “divine excess” in all forms. “We are their cattle. We are being bred for slavery,” the scientist proclaims. Carpenter saw around him a self-obsessed consumer culture addicted to escape—an America that seemed to get its values and culture from television, and he sought to rebel against it.

Carpenter’s outrage represents an anti-establishment, arguably Marxist theme, as the estrangement of the proletariat leads to their rebellion. The impending rebellion is evident from the first scenes, when Nada looks for work and finds the food stamp program has been canceled due to a computer error, and his unemployment officer, growing impatient, says there’s no work for him. Similarly, Frank seems to embody an angered class of working homeless who can maintain a job, but nevertheless, he does not earn enough to support his family in Detroit. He notes the hypocrisy of a capitalist society, saying, “Do what you can to get ahead, but I’m going to do my best to blow you away.” Frank questions how notions of helping your fellow man or prosperity for everyone can exist in a world of free enterprise and competition. Frank’s point of view, and indeed Carpenter’s, could be seen as Marxist in nature for how they see an inequality and inhumanity in the socioeconomic order of classes. “They close one more factory we should take a sledgehammer to one of their fancy fuckin foreign cars,” Frank says. Carpenter’s views, Marxist or not (he maintains they are not), remain in conflict with contemporary American culture, and therefore are decidedly cultish.

They Live also condemns crimes of racial and social injustices perpetuated by the elitist alien race. Gentrification and race play conspicuous thematic roles in the film, as the aliens hide behind an exclusively white capitalist culture. By contrast, the poor neighborhoods consist of multi-ethnic backgrounds steeped in socioeconomic deficiencies. Their shantytown community, ironically called Justiceville, sits across the street from a Spanish-style church dwarfed by the surrounding concrete jungle of downtown Los Angeles. Eventually, Justiceville receives a treatment of bulldozers and armored (all white) police to clear the area, in part to weed out those who conspire against the alien overlords, in part to make way for more sterile structures of the super-rich (an sequence that eerily foretells the Rodney King beating as they club the blind preacher to death). At one point, Frank tells Nada to leave him alone, that he has a job and wants to keep it. “I’m walking a white line all the time. I don’t bother nobody. Nobody bothers me. You Better start doin’ the same,” and then Nada replies, “White line’s in the middle of the road. That’s the worst place to drive.” This exchange may reference “The Color Line,” Frederick Douglass’ 1881 essay about racial segregation in the U.S., and suggests Nada’s sympathy for Frank’s racial marginalization.

They Live also condemns crimes of racial and social injustices perpetuated by the elitist alien race. Gentrification and race play conspicuous thematic roles in the film, as the aliens hide behind an exclusively white capitalist culture. By contrast, the poor neighborhoods consist of multi-ethnic backgrounds steeped in socioeconomic deficiencies. Their shantytown community, ironically called Justiceville, sits across the street from a Spanish-style church dwarfed by the surrounding concrete jungle of downtown Los Angeles. Eventually, Justiceville receives a treatment of bulldozers and armored (all white) police to clear the area, in part to weed out those who conspire against the alien overlords, in part to make way for more sterile structures of the super-rich (an sequence that eerily foretells the Rodney King beating as they club the blind preacher to death). At one point, Frank tells Nada to leave him alone, that he has a job and wants to keep it. “I’m walking a white line all the time. I don’t bother nobody. Nobody bothers me. You Better start doin’ the same,” and then Nada replies, “White line’s in the middle of the road. That’s the worst place to drive.” This exchange may reference “The Color Line,” Frederick Douglass’ 1881 essay about racial segregation in the U.S., and suggests Nada’s sympathy for Frank’s racial marginalization.

Carpenter’s thorough upheaval rallies against politics, economic institutions, mass media culture, and racial injustices, but in a larger sense, he hopes to shake his audience out of their indifference. Apathy runs rampant in American culture; from sociopolitical issues to environmental breakdown, The System keeps us comfortable to keep apathy alive and well. Social media, television, and movies, and the broad multi-demographic appeal across these diversions, keep everyone too busy to bother complaining in any substantial way. It’s enough to fill out an online petition to stop this or that political atrocity, and then click back to the latest celebrity news item. In a world where nothing makes sense to a lot of Americans, a film like They Live presents an intriguing and relevant escapist concept: those driven by money and power, who celebrate celebrity and wealth, who ignore environmental warning signs that will inevitably result in a warmer climate, may as well be aliens trying to secure control and adjust the climate for their needs. As a result, the film’s “sleep” metaphor remains profound and appropriate. Subliminal signs read “Stay Asleep” and crosswalks send out a hidden frequency telling us to “Sleep.” The rebel scientists attempt to break through the alien signals, warning in their scrambled television message, “They are dismantling the sleeping middle class. More and more people are becoming poor.” But upon seeing the scientist’s warning, those watching get a headache and change the channel. It’s a sad day indeed when the crazed, blind street preacher offers the best assessment of American culture—“Our owners” run everything.

Carpenter suggests people have become victims; The Powers That Be have shaped their senses in a complicit state of sleep, unconscious and open to suggestion like a voodoo zombie. With perceptions skewed by some clandestine force, only Hoffman lenses clarify and rouse their user from their slumber, transferring the user into a conscious state. Carpenter’s vision for the truth represents a time informed by Classic Hollywood values—before Reaganomics outweighed more classical, romantic motivations, like doing good within the community or enforcing justice for all. Therefore, Carpenter’s truth appears in black-and-white, a decidedly cinematic conception of reality that harkens back to The Wizard of Oz in 1938. Both They Live and The Wizard of Oz consider sleep to be an entry point into an artificial fantasy world, a brash and glitzy place that circumvents the harsher truths of reality. Putting on the glasses in They Live filters out the artifice bolstered by the alien ruling class. Philosopher and Lacanian psychoanalyst Slavoj Žižek remarked on the significance of the glasses in his film The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2012), saying the glasses “function like a critique of ideology. They allow you to see the real message beneath all the propaganda, glitz, posters and so on… You see the dictatorship in democracy, the invisible order which sustains your apparent freedom.” In another way, the idea of colorization reflects an unfortunate trend of the period. Ted Turner had purchased the classic Hollywood catalogue of studios like Warner Bros., MGM, and RKO to be showcased on his cable network, Turner Classic Movies. In doing so, Turner opted to update hundreds of titles, such as Casablanca, King Kong, and It’s a Wonderful Life. Carpenter saw this as emblematic of something corrupt and criminally commercial, and he likened colorization to an artificiality in They Live: “It’s as if the aliens have colorized us. That means, of course, that Ted Turner is really a monster from outer space.”

Carpenter suggests people have become victims; The Powers That Be have shaped their senses in a complicit state of sleep, unconscious and open to suggestion like a voodoo zombie. With perceptions skewed by some clandestine force, only Hoffman lenses clarify and rouse their user from their slumber, transferring the user into a conscious state. Carpenter’s vision for the truth represents a time informed by Classic Hollywood values—before Reaganomics outweighed more classical, romantic motivations, like doing good within the community or enforcing justice for all. Therefore, Carpenter’s truth appears in black-and-white, a decidedly cinematic conception of reality that harkens back to The Wizard of Oz in 1938. Both They Live and The Wizard of Oz consider sleep to be an entry point into an artificial fantasy world, a brash and glitzy place that circumvents the harsher truths of reality. Putting on the glasses in They Live filters out the artifice bolstered by the alien ruling class. Philosopher and Lacanian psychoanalyst Slavoj Žižek remarked on the significance of the glasses in his film The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2012), saying the glasses “function like a critique of ideology. They allow you to see the real message beneath all the propaganda, glitz, posters and so on… You see the dictatorship in democracy, the invisible order which sustains your apparent freedom.” In another way, the idea of colorization reflects an unfortunate trend of the period. Ted Turner had purchased the classic Hollywood catalogue of studios like Warner Bros., MGM, and RKO to be showcased on his cable network, Turner Classic Movies. In doing so, Turner opted to update hundreds of titles, such as Casablanca, King Kong, and It’s a Wonderful Life. Carpenter saw this as emblematic of something corrupt and criminally commercial, and he likened colorization to an artificiality in They Live: “It’s as if the aliens have colorized us. That means, of course, that Ted Turner is really a monster from outer space.”

Of course, They Live does not provide a sound or even particularly rational argument against The System or its Apparatuses—the film is a pure denouncement of its targets. The ideological themes above saturate the film, which the viewer must remember is a B-grade production, after all. Carpenter’s ideological stance is imperfect and sometimes contradictory, even though he engages in minor meta-commentaries with the film. Consider how after the alien signal goes out, some nightspot patrons see an episode of At the Movies with Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, except Siskel is an alien who remarks, “Filmmakers like George Romero and John Carpenter have to show some restraint.” Carpenter marches against authority, but he cannot resist having fun as a filmmaker. As a result, there is a curious balance between angered commentary and cheesy cult entertainment, a mixture personified by the last-minute appearance of a woman’s breasts (the only nudity in the film) in the last shots. The breasts represent its cult status through a last-minute effort to end the film with a one-two punch of boobs and levity. The scene, however amusing, may undermine the film’s outrage. In another sense, They Live supports the very aspects of American culture that Carpenter seeks to denounce. The 1980s worshiped a sort of excessive and hypermasculine style represented in They Live. And while any film that attempts to stand against capitalism proves innately paradoxical given the commercial requirements of cinema, if there could be a best-of-both-worlds to such a paradox, They Live would be it.

“You ain’t the first sonofabitch to wake up outta their dream,” Nada tells Frank. To be sure, Carpenter hopes to stir his audience from the cultural inertia by lashing out at anyone and everyone in They Live. The film’s transgressive, anti-authoritarian stance revitalizes Carpenter’s already built-in cult audience of horror, science-fiction, fantasy, pro-wrestling, and action fanatics. In cult groups, the They Live alien symbolizes corrupt, inhuman ambition that steps on the little guy, resulting in dozens of images, posters, and t-shirts in which real-life celebrities and politicians (Donald Trump is a popular figure) appear as the film’s aliens. And while Carpenter’s following laid the foundation of They Live’s cult status, its cult status has only sharpened since. Things today are not so different than 1988; they are just mediatized and presented on such a variety of screens to an outlandish degree. The resulting outrage culture feeds on artificial and exaggerated online expressions, if only because they bring attention to their source. Even as such modern examples of outrage remain prevalent, noticing the emergent trends of racism, social injustice, misogyny, and capitalist control prove more difficult to track and attempt to correct within the more extensive and elaborate cultural framework. The sheer volume of texts and contexts available lessens the potency of any single source, while their sum total is blinding by comparison. Individual examples of artistic protest aside, Carpenter seems to step back with They Live and, just as Nada does before his death, looks to his audience and flashes his middle finger for a final, glorious F-U.

“You ain’t the first sonofabitch to wake up outta their dream,” Nada tells Frank. To be sure, Carpenter hopes to stir his audience from the cultural inertia by lashing out at anyone and everyone in They Live. The film’s transgressive, anti-authoritarian stance revitalizes Carpenter’s already built-in cult audience of horror, science-fiction, fantasy, pro-wrestling, and action fanatics. In cult groups, the They Live alien symbolizes corrupt, inhuman ambition that steps on the little guy, resulting in dozens of images, posters, and t-shirts in which real-life celebrities and politicians (Donald Trump is a popular figure) appear as the film’s aliens. And while Carpenter’s following laid the foundation of They Live’s cult status, its cult status has only sharpened since. Things today are not so different than 1988; they are just mediatized and presented on such a variety of screens to an outlandish degree. The resulting outrage culture feeds on artificial and exaggerated online expressions, if only because they bring attention to their source. Even as such modern examples of outrage remain prevalent, noticing the emergent trends of racism, social injustice, misogyny, and capitalist control prove more difficult to track and attempt to correct within the more extensive and elaborate cultural framework. The sheer volume of texts and contexts available lessens the potency of any single source, while their sum total is blinding by comparison. Individual examples of artistic protest aside, Carpenter seems to step back with They Live and, just as Nada does before his death, looks to his audience and flashes his middle finger for a final, glorious F-U.

Bibliography:

Althusser, Louis. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Penguin, 1971.

Boulenger, Gilles. John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness.H.O.M. Vision, 2002.

Carpenter, John, director. “Independent Thoughts – An Interview With Writer/Director John Carpenter.” They Live. 1988. Blu-ray. Shout! Factory, 2012.

Cumbow, Robert C. Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter. Scarecrow Press, Inc.; Second Edition, 2000.

David, Keith, actor. “Man Vs. Aliens – An Interview With Actor Keith David.” They Live. 1988. Blu-ray. Shout! Factory, 2012.

Fiennes, Sophie, director. The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. Zeitgeist Films, 2012. DVD.

Grant, Barry Keith. “Disorder in the Universe: John Carpenter and the Question of Genre.” The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror, edited by Ian Conrich et al. Columbia University Press, 2004, pp. 10-20.

Leayman, Charles D. “As Always with Carpenter, Technique Far Outdistances Content.” Cinefantastique, vol. 19, #4, May 1989.

Maslin, Janet. “A Pair of Sunglasses Reveals a World of Evil.” The New York Times. 4 November 1988. http://www.nytimes.com/1988/11/04/movies/review-film-a-pair-of-sunglasses-reveals-a-world-of-evil.html. Accessed 10 June 2017.

Mathijs, Ernest, and Xavier Mendik, editors. The Cult Film Reader. Open University Press, 2008, pp. xvii-25.

Muir, John Kenneth. The Films of John Carpenter. McFarland, 2000.

Nelson, Ray. “Nada.” Alien Encounters, #6, April 1986. Eclipse Comics.

Swires, Steve. “John Carpenter & the Invasion of the Yuppie Snatchers.” Starlog, vol. 136, November 1988, pp. 37-40. Archive.org. https://archive.org/details/starlog_magazine-136. Accessed 7 June 2017.

Wilson, Harlan D. They Live. New York: Wallflower Press, 2015.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review