The Definitives

The Searchers

Essay by Brian Eggert |

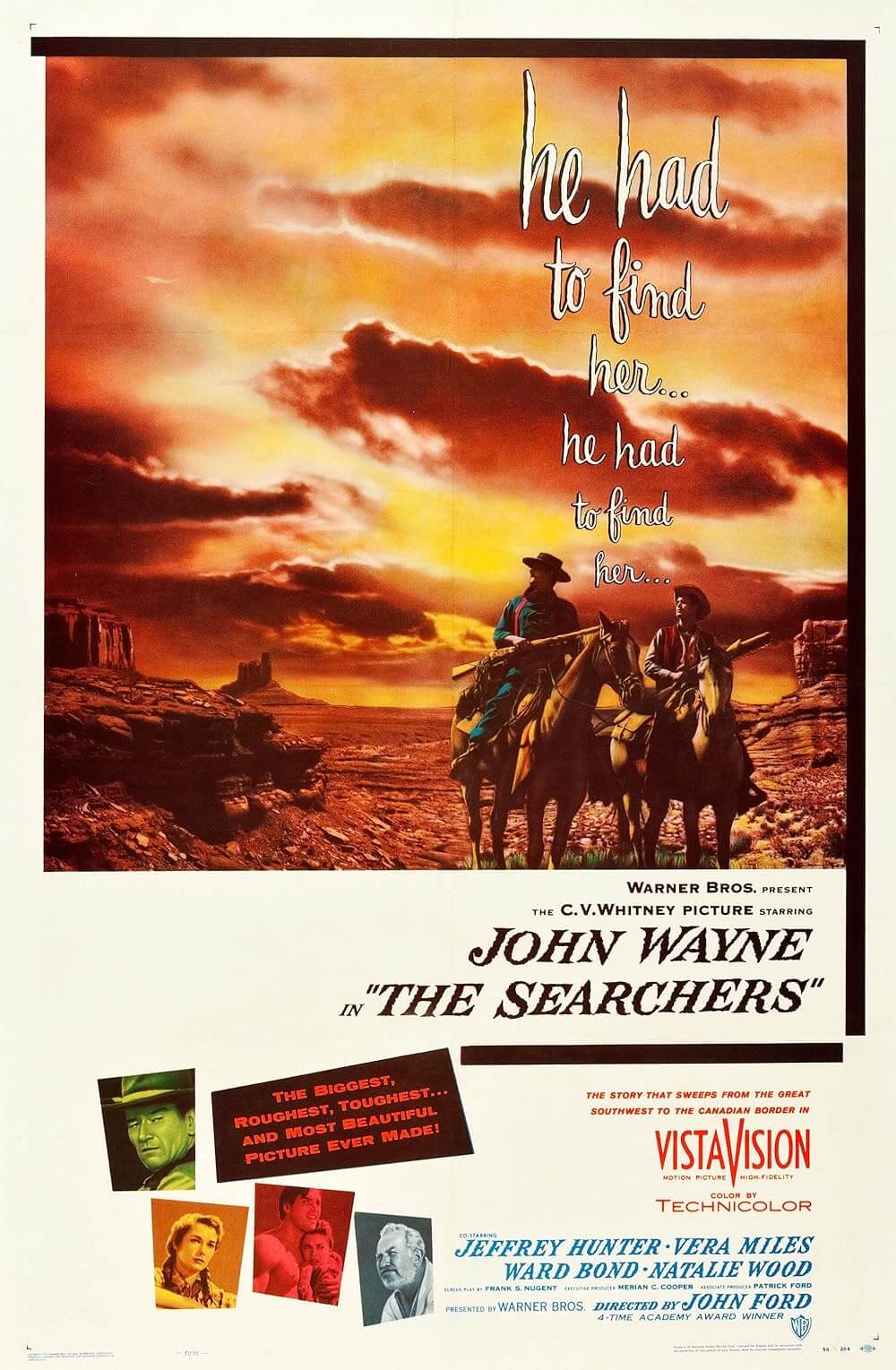

In terms of classical storytelling, The Searchers, John Ford’s most compelling Western, avoids association with the genre’s established precepts. On the surface, Western form is obeyed to the mark: The film stars John Wayne, an actor eternally linked to Westerns, perhaps giving his best performance in any Ford film, among them veritable diagrams of filmic convention such as 1939’s Stagecoach. Photographed in the director’s cinematic nesting ground of Monument Valley, it contains painterly images of majestic scenery, some of the most remarkable ever captured. Historians and film scholars attest to its supremacy and recognize its influence on the medium and the artists working therein. And yet, the motion picture Ford considered his own masterpiece confronts prior standards, meets issues of revenge and discrimination within a ponderous text, and revises the director’s Western model forevermore.

By 1955 when production began, The Searchers would be Ford’s first Western in five years, a personal risk after a number of commercial failures and artistic missteps caused him to contemplate retirement. Having all but invented the genre, as far back as 1917 the director made Westerns, embracing their straight-lined plots and grandiose vistas, building himself an ideal derived from American painting, the era’s dime novels, and period lore—all integrated into his own historical reality on film. Pictures like The Iron Horse, My Darling Clementine, and Wagon Master fastened the filmmaker’s name to the genre, and they inspire his many followers, among them auteurs like Akira Kurosawa, Ingmar Bergman, and Orson Welles. Questioning the intention of The Searchers comes naturally, as beyond its unequivocal beauty and dramatic intensity, there exists what appear to be incompatible narrative developments, symbolism, and thematic undercurrents signifying the end product as being at odds with itself. Ford rethinks his customary strategy with the film, embracing what other filmmakers like Anthony Mann (Man of the West, The Naked Spur) had already done by this time, and produces an architecturally revisionist Western. The film is “revisionist” in the sense that the genre’s traditional adherence to Westward Expansion neither represents the primary motivation of its main character nor its narrative campaign.

The Searchers begins when Ethan Edwards (Wayne) returns to his brother’s home oddly set in a desolate but beautiful section of northern Texas. Raiding Comanches attack soon after, leaving his brother, sister-in-law Martha, and their son dead, and their two girls Lucy (Pippa Scott) and Debbie (later played by Natalie Wood) kidnapped. After finding Lucy dead, the next five years of Ethan’s life entail a Homeric pursuit to find young Debbie, probing rugged landscape and despairing circumstances, enduring the toils of the quest to do what he believes merciful: kill her. Being tainted by years with the “Indians” Ethan so hates, Debbie, he believes, is unsalvageable. Ethan’s wandering, elliptical journey is contrary to the very nature of the Western, which, prior to The Searchers, habitually followed a set narrative path forward, specifically in a westerly direction. Good guys are good; bad guys are bad—intrinsically, the “good” embark on a mission of Manifest Destiny to tame The Promised Land, while the “bad” embody either The Wild West in need of taming or an obstacle to overcome before proceeding westward. Doing so meant not only charting new and wondrous territory, but finding “God’s Wilderness.” Mid-19th Century explorers viewed the West as a Garden of Eden, ironically so, since the lawless terrain became a breeding ground for criminality in all its forms. The West was not deemed America, rather that which was to become America. Settled in the Eastern Colonies were Americans; beyond the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers was a vast rolling wildness waiting to be surveyed and triumphed over. Surmounting that open landscape led to the “taming” of our instinct to expand and, eventually, settle down with a family. “Go West, young man, and grow up with the country,” were Horace Greely’s famous words in 1859, suggesting the Land of Milk and Honey was a place to become a man, and claim land and a family in the process.

The Searchers begins when Ethan Edwards (Wayne) returns to his brother’s home oddly set in a desolate but beautiful section of northern Texas. Raiding Comanches attack soon after, leaving his brother, sister-in-law Martha, and their son dead, and their two girls Lucy (Pippa Scott) and Debbie (later played by Natalie Wood) kidnapped. After finding Lucy dead, the next five years of Ethan’s life entail a Homeric pursuit to find young Debbie, probing rugged landscape and despairing circumstances, enduring the toils of the quest to do what he believes merciful: kill her. Being tainted by years with the “Indians” Ethan so hates, Debbie, he believes, is unsalvageable. Ethan’s wandering, elliptical journey is contrary to the very nature of the Western, which, prior to The Searchers, habitually followed a set narrative path forward, specifically in a westerly direction. Good guys are good; bad guys are bad—intrinsically, the “good” embark on a mission of Manifest Destiny to tame The Promised Land, while the “bad” embody either The Wild West in need of taming or an obstacle to overcome before proceeding westward. Doing so meant not only charting new and wondrous territory, but finding “God’s Wilderness.” Mid-19th Century explorers viewed the West as a Garden of Eden, ironically so, since the lawless terrain became a breeding ground for criminality in all its forms. The West was not deemed America, rather that which was to become America. Settled in the Eastern Colonies were Americans; beyond the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers was a vast rolling wildness waiting to be surveyed and triumphed over. Surmounting that open landscape led to the “taming” of our instinct to expand and, eventually, settle down with a family. “Go West, young man, and grow up with the country,” were Horace Greely’s famous words in 1859, suggesting the Land of Milk and Honey was a place to become a man, and claim land and a family in the process.

Whereas Ford’s early career Westerns ingrain hardy sentimental fondness for writer John L. O’Sullivan’s proposed mission to the Pacific, believed to be “divine,” the director’s later films, including The Searchers, understood that finally reaching The Last Frontier meant finding a Dead End. After all the Westerns in Ford’s long career, few break from a familiar series of archetypes, the majority concerning men, predominantly white, subject to the perils of the West: the elements, Native Americans, nature, themselves, corruption, and the unknown. Shaped by their stations, characters are exposed to all manner of temptation and influence, thrust about, meanwhile preserving the significance of their charge westward. Beneath these thick narrative brushstrokes resides an underpainting where Ford rests his camera, using low angles to aggrandize heroes and their backdrops, leaving the image stationary so the action within the frame breeds a sense of unrest on the landscape.

The Searchers signifies a defining moment in Ford’s filmography where he ceases to purport that the push across the Plains and over the Rockies was a dreamily romantic voyage of cultural discovery and accomplishment, and instead suggests, even if Hollywood was not prepared to listen, that there are consequences. Ford’s message inhabits the realm of the allegorical and psychological, avoiding any outright, condemning dialogue on the matter (like that heard later in Ford’s last Western, Cheyenne Autumn from 1964). The film’s commentary is hidden deep in the subtext, where observations are occasionally lost or misinterpreted when placed next to its lighter notes of comic relief and romantic folly, no doubt included by the filmmaker for his mainstream audience’s benefit. For every harsh outlook declared by John Wayne’s racist hero Ethan Edwards, a more frivolous scene follows to ease the viewer, creating a contradictory, yet brilliant and strangely rewarding marriage of light entertainment and dark territory.

The Searchers signifies a defining moment in Ford’s filmography where he ceases to purport that the push across the Plains and over the Rockies was a dreamily romantic voyage of cultural discovery and accomplishment, and instead suggests, even if Hollywood was not prepared to listen, that there are consequences. Ford’s message inhabits the realm of the allegorical and psychological, avoiding any outright, condemning dialogue on the matter (like that heard later in Ford’s last Western, Cheyenne Autumn from 1964). The film’s commentary is hidden deep in the subtext, where observations are occasionally lost or misinterpreted when placed next to its lighter notes of comic relief and romantic folly, no doubt included by the filmmaker for his mainstream audience’s benefit. For every harsh outlook declared by John Wayne’s racist hero Ethan Edwards, a more frivolous scene follows to ease the viewer, creating a contradictory, yet brilliant and strangely rewarding marriage of light entertainment and dark territory.

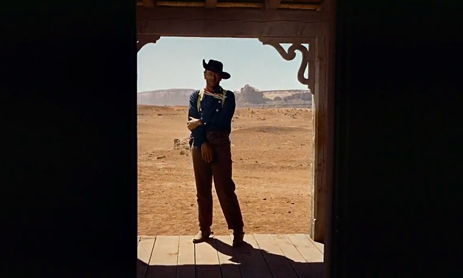

Despite the film’s attempts to reduce its own severity, The Searchers sets up a remarkably grim set of conditions, ranging from the landscape to individual character histories. The first iconic shot (mirrored by the film’s last iconic shot) of Martha opening the front door seems to frame the outer terrain like a photograph, where within an isolating desert appears, open to the elements, offering a curiously unprotected and vulnerable locale for the Edwards’ home—particularly in view of subsequent talk of the omnipresent Comanche threat. The unveiled farm remains open to attack, ignorantly, if not arrogantly facing the dangers that surround them. Ethan appears outside, finally returning home, as by the film’s 1868 setting The Civil War has been over for three years. Clearly Ethan refuses to surrender, still sporting his Confederacy garb and lance, clinging to a lost cause, and having long since settled with the accompanying alienation and estrangement. He appears glad to be home and willing pay his way, with a small wealth of suspiciously unscuffed gold no less. Reverend-Captain Clayton (Ward Bond) asserts that Ethan “’fits a lot of descriptions,” implying Ethan is a wanted man. With little respect for religious processions, Ethan openly disrupts both a funeral and a wedding in the expanse of the film, seeing those convictions as weakness. He later shoots out the eyes of a dead Comanche to prevent his spirit from passing into the next world; Ethan does this, he says, not because he believes such a principle, but because the Comanche do. His running motto, “That’ll be the day,” is spoken in Wayne’s swagger-of-a-voice, which he tenders whenever challenged.

This hard-edged, opaque description leaves us fascinated but unsure about our hero. Promptly clarified, Ethan’s hatred for Native Americans is our only certainty. “A fella could mistake you for a half-breed,” he says to his brother’s adopted son, Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter). “Not quite, I’m eighth-Cherokee, the rest is Welsh and English,” replies Martin, “Least that’s what they tell me.” Ethan sends him a wary look, the small percentage of “Indian” being blood enough to evoke distrust. And yet, his prejudice does not compare to the racist fury compelling him to continue on his five-year trail to rescue Debbie from her captors, or rather kill away their influence over her. ”Livin’ with Comanches ain’t being alive,” Ethan growls. He would rather see her dead.

This hard-edged, opaque description leaves us fascinated but unsure about our hero. Promptly clarified, Ethan’s hatred for Native Americans is our only certainty. “A fella could mistake you for a half-breed,” he says to his brother’s adopted son, Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter). “Not quite, I’m eighth-Cherokee, the rest is Welsh and English,” replies Martin, “Least that’s what they tell me.” Ethan sends him a wary look, the small percentage of “Indian” being blood enough to evoke distrust. And yet, his prejudice does not compare to the racist fury compelling him to continue on his five-year trail to rescue Debbie from her captors, or rather kill away their influence over her. ”Livin’ with Comanches ain’t being alive,” Ethan growls. He would rather see her dead.

Herein rests the easiest assault against The Searchers—that the Westerns of John Ford, and therefore many early filmmakers working in the genre, unrepentantly place Native Americans in the role of villains, primarily as ambiguous Other figures to be feared. Ford’s portrayal was often negative, with a few exceptions, because the director was so bound to that Manifest Destiny ideal that saw Native Americans as a problem, a people to be “swept aside” in favor of westward expansion. Purveyed in the ongoing myths about the period, they were the “noble savages” to contrast “the quintessential frontiersmen” of the cowboys. Today scholars use the term “Indians”, versus “Native Americans”, in specific reference to their Hollywoodization and exploitation, and in regard to their context within the Western genre. Indeed, Ford realized his use of Indians was unfair, even contemptible. “I’ve killed more Indians than Custer, Beecher, and Chivington put together,” he admitted. “And people in Europe always want to know about the Indians… Let’s face it, we’ve treated them very badly—it’s a blot on our shield; we’ve cheated and robbed, killed, murdered, massacred and everything else, but they kill one white man and God, out come the troops.” Ford was sympathetic to the cause of Native Americans offscreen, and in later films, including The Searchers, he avoids showing any of the more atrocious acts committed by Indians within the story, just the white man’s retaliation. For example, Ethan arrives at his brother’s home after it has been set afire and his family ravaged; he finds Lucy dead though her body never appears onscreen. Even Debbie’s kidnapping is suggested with only a glare from the film’s villain, Chief Scar (Henry Brandon), and his looming shadow.

Though employing them as villainous characters in broadly defined yarns, Ford also censured the white man for his cruel, genocidal attitude toward the Indian. Consider the scene where Ethan shoots down as many buffalo as he can, hoping to dwindle the Indians’ food supply. But more than just food, buffalo represent the very livelihood of Native Americans, as Francis Parkman wrote: “The buffalo supplies them with almost all the necessities of life; with habitations, food, clothing, and fuel; with strings for their bows, with thread, cordage and trailropes for their horses, with coverings for their saddles, with vessels to hold water, with boats to cross streams, with glue, and with the means of purchasing all that they desire from the traders.” With each buffalo gunned down, Ethan destroys the livelihood of his enemy, ostensibly executing a group of Indians with every precise shot. Ford saw Native Americans as a natural part of the western landscape, not implicitly violent unless tempted by the intruding, cruel white man. His silent-era epic The Iron Horse features villain-Indians led by a white man; Drums Along the Mohawk and Fort Apache each offer Indian attacks only after being provoked by white man’s disturbance of their land—their violence is sharp and cunning, but in reprisal to broken agreements and double-crosses dealt by white people. Ford would prefer an understanding of cultures and includes Martin Pawley as a symbol of hope for both races to merge communally and develop a peaceful understanding, and thus allows Martin to enter a fruitful romance with the neighbor girl Laurie Jorgensen (Vera Miles). Furthermore, Ethan’s eventual, shall we say, tolerance of Martin, allowing the “half-breed” to accompany him on the five-year trek, also suggests his racism will subside in the end.

Though employing them as villainous characters in broadly defined yarns, Ford also censured the white man for his cruel, genocidal attitude toward the Indian. Consider the scene where Ethan shoots down as many buffalo as he can, hoping to dwindle the Indians’ food supply. But more than just food, buffalo represent the very livelihood of Native Americans, as Francis Parkman wrote: “The buffalo supplies them with almost all the necessities of life; with habitations, food, clothing, and fuel; with strings for their bows, with thread, cordage and trailropes for their horses, with coverings for their saddles, with vessels to hold water, with boats to cross streams, with glue, and with the means of purchasing all that they desire from the traders.” With each buffalo gunned down, Ethan destroys the livelihood of his enemy, ostensibly executing a group of Indians with every precise shot. Ford saw Native Americans as a natural part of the western landscape, not implicitly violent unless tempted by the intruding, cruel white man. His silent-era epic The Iron Horse features villain-Indians led by a white man; Drums Along the Mohawk and Fort Apache each offer Indian attacks only after being provoked by white man’s disturbance of their land—their violence is sharp and cunning, but in reprisal to broken agreements and double-crosses dealt by white people. Ford would prefer an understanding of cultures and includes Martin Pawley as a symbol of hope for both races to merge communally and develop a peaceful understanding, and thus allows Martin to enter a fruitful romance with the neighbor girl Laurie Jorgensen (Vera Miles). Furthermore, Ethan’s eventual, shall we say, tolerance of Martin, allowing the “half-breed” to accompany him on the five-year trek, also suggests his racism will subside in the end.

Nevertheless, The Searchers implicates itself on a number of occasions. Take the frivolous subplot where Martin’s trades hats for a blanket and “squaw” wife by mistake; he angrily kicks her down a hill in rejection, a scene meant to provide humor but instead is cringe-inducing in its heartlessness. Barring such light comedy at the Native Americans’ expense, the film addresses racism and sparks communication by Ethan’s inner battle to overcome his bigotry, prefacing the external arguments made in Cheyenne Autumn, an absolute reproach against the mistreatment, segmentation, and relocation of native tribes. Hollywood’s defense of Native Americans, well, there was really little of that to speak of… And so, Ford’s film does not sanction or regret racism; it simply acknowledges its existence and presents a story wherein its reality fuels his protagonist’s dissension. That in itself steers a new and important cultural breakthrough in cinema: the acknowledgment that there is undeniably a problem requiring attention, that a racist hero is explicitly an inharmonious one. Ford gives Ethan five long years on an interpersonal odyssey to resolve his existential dilemma, developing Ethan and Martin’s relationship as they camp together every night—a devout racist and a man otherwise defined by his “hybridity”. Perhaps that time softens Ethan’s hatred, and perhaps not. Ethan’s inward journey, where through he realizes his love for Debbie is greater than his hatred for Scar and the Comanche Indians, characterizes the film’s fundamental struggle. Whether or not Ethan and Martin actually find Debbie is less the fear than what Ethan will do when he finds her. Will he kill her? Ford asks that we question our hero, his motives and origins. He is a duty-bound military man crutching on his anguished past, seemingly a living representation of westward expansion and its immanent flaws. And yet, Ethan is unusually familiar with Indian customs. When Ethan discovers the location of the group responsible for Debbie’s kidnapping, he and Martin ride to survey the situation, posing as traders. Ethan and Scar come to stand opposite each other—racial and cultural antitheses, but otherwise the same role. Mirroring images, they stand on equal footing (Wayne a few inches taller than Brandon), both renegades, both acquainted with the other’s culture. Ethan reveals he speaks Comanche; Scar speaks “American”.

A clue to Ethan’s hatred for Comanche Indians appears early in the film, when the younger Debbie goes to her hiding place before Scar first attacks the Edwards’ home. She kneels down in the graveyard by a headstone, which, appearing for only a few frames, reads: “Here lies Mary Jane Edwards killed by Comanches May 12, 1852. A good wife and mother in her 41st year.” Sixteen years earlier, was Ethan’s own mother massacred by Comanches? Does this motivate his relentless pilgrimage and remorseless treatment of Indians? And his knowledge of Comanche rituals, taking the time to learn their language, is this merely getting to know one’s enemy, or something more? The Searchers resists giving answers, or even playing-out like a typical Western where the “hero” kills the “villain” by letting Ethan kill Scar, and instead places emphasis on the circular narrative of Ethan’s psychological disarray. In the finale when Ethan, Martin, Captain Clayton and his men charge the Comanche camp, Scar is killed by Martin. Ethan is left with his own demons to conquer, but not before he scalps Scar’s dead body with tragic irony, further identifying himself as analogous to his enemy. Ethan embraces the moment all the same (an act originally introduced to Native American’s by the French, though rarely is that historical association made). This act of Ethan scalping seems to suggest a crescendo of horror: If Ethan breaks a code of honor by scalping scar, surely Debbie’s fate can be no better.

A clue to Ethan’s hatred for Comanche Indians appears early in the film, when the younger Debbie goes to her hiding place before Scar first attacks the Edwards’ home. She kneels down in the graveyard by a headstone, which, appearing for only a few frames, reads: “Here lies Mary Jane Edwards killed by Comanches May 12, 1852. A good wife and mother in her 41st year.” Sixteen years earlier, was Ethan’s own mother massacred by Comanches? Does this motivate his relentless pilgrimage and remorseless treatment of Indians? And his knowledge of Comanche rituals, taking the time to learn their language, is this merely getting to know one’s enemy, or something more? The Searchers resists giving answers, or even playing-out like a typical Western where the “hero” kills the “villain” by letting Ethan kill Scar, and instead places emphasis on the circular narrative of Ethan’s psychological disarray. In the finale when Ethan, Martin, Captain Clayton and his men charge the Comanche camp, Scar is killed by Martin. Ethan is left with his own demons to conquer, but not before he scalps Scar’s dead body with tragic irony, further identifying himself as analogous to his enemy. Ethan embraces the moment all the same (an act originally introduced to Native American’s by the French, though rarely is that historical association made). This act of Ethan scalping seems to suggest a crescendo of horror: If Ethan breaks a code of honor by scalping scar, surely Debbie’s fate can be no better.

In the film’s most memorable scene, one of the greatest single moments of all cinema, Ethan emerges from Scar’s tent on his horse and spots Debbie, who, dressed in full Comanche attire, runs in terror. Ethan chases her down a hill and corners her, Martin trailing behind yelling “No!” for Ethan not to do what he has intended to do from the outset. Ethan gets off his horse and picks Debbie up, raises her in the air like a child, the fear radiating from her. He lowers her into his arms, and says, “Let’s go home, Debbie.” Could it be that after Scar’s death and scalping some valve releases Ethan’s rage, permitting him to finally view Debbie as not an object taken and since tainted, but as his niece? In the face of saving Debbie, Ethan can neither claim his redemption nor have the happy ending the film’s other characters enjoy. For the last shot, Ford places the camera in the front door of the Jorgensen’s, Debbie’s new home. The shot pulls back as the Jorgensen’s enter with Debbie, Martin and Laurie following behind, the perfect symmetry again framing the wild desert. Ethan remains just outside, gripping his arm as if injured. Ford seems to suggest that Ethan has not yet settled whatever conflict still rages inside. Is this Ethan’s lingering racism? In a way, does he still want Debbie dead? If so, he cannot truly be at peace, and so he must continue his drive.

Ford denies his audience any closure with Ethan’s character, leaving clarity of purpose and motivations altogether ambiguous, intentionally so. He altered the script by Frank S. Nugent, based on the novel by Alan LeMay, deleting any explanation expounded within. Ford goes against the script, which featured a “happy ending” complete with Ethan entering the Jorgensen’s home; he removed explicatory dialogue that shed light on why Ethan does not kill Debbie; and he added the scene where Ethan scalps scar. With these scenes changed, backed by his confidence in his own vision, John Ford amends The Searchers from a traditional Hollywood Western into an uncommon human tragedy. The director even worked closely with Stan Jones, writer of the film’s song “The Searchers”, which plays over the opening credits and the final scene in front of the Jorgensen’s. Westerns are often bookended with a song, but none as appropriate as this, informed by Ford’s influence on the lyrics: “What makes a man to wander? What makes a man to roam? What makes a man leave bed and board, and turn his back on home? A man will search his heart and soul, go searchin’ way out there. His peace of mind he knows he’ll find, but where, oh lord, lord where? Ride away, ride away, ride away…”

Ford denies his audience any closure with Ethan’s character, leaving clarity of purpose and motivations altogether ambiguous, intentionally so. He altered the script by Frank S. Nugent, based on the novel by Alan LeMay, deleting any explanation expounded within. Ford goes against the script, which featured a “happy ending” complete with Ethan entering the Jorgensen’s home; he removed explicatory dialogue that shed light on why Ethan does not kill Debbie; and he added the scene where Ethan scalps scar. With these scenes changed, backed by his confidence in his own vision, John Ford amends The Searchers from a traditional Hollywood Western into an uncommon human tragedy. The director even worked closely with Stan Jones, writer of the film’s song “The Searchers”, which plays over the opening credits and the final scene in front of the Jorgensen’s. Westerns are often bookended with a song, but none as appropriate as this, informed by Ford’s influence on the lyrics: “What makes a man to wander? What makes a man to roam? What makes a man leave bed and board, and turn his back on home? A man will search his heart and soul, go searchin’ way out there. His peace of mind he knows he’ll find, but where, oh lord, lord where? Ride away, ride away, ride away…”

Ford was particularly proud of The Searchers, as was Wayne, who named his son Ethan after his character. The film’s initial critical reception, however, lacked passion, as did its box office receipts, and Ford was devastated by its apparent dismissal. But the picture’s reputation would grow over time, earning recognition on top film lists (such as AFI and Sight & Sound) and through homages paid by modern filmmakers. Using the film’s influential framework by borrowing a familiar lead character and surrounding outline, directors like Steven Spielberg (with Close Encounters of the Third Kind) and Martin Scorsese (with Taxi Driver) have helped express the film’s importance and lasting authority. Western filmmakers like Anthony Mann, Sergio Leone, and Clint Eastwood have paid tribute by conceiving revisionist Westerns not wholly reliant on the “white conquest” plot, and that contain a plagued main character on parallel with Ethan Edwards. John Ford’s authorship of a story exploring the human costs in the conventional Western is the most significant mark of the film, seeing as by 1956 the director had committed almost fifty Westerns to celluloid. The Searchers begins to unravel like a linear Western yarn, but is thrown into revolution by Ethan, a tragic hero fated to forever prospect his soul for a golden answer. Subversive in structure, the film orbits around its environment, broods over its emotions, and offers no finality to Ethan Edwards’ conflict. Cinema’s most renowned idealist of the American West suddenly altered the schema, which he played a central role in establishing, and in that welcomes a massive reconsideration of those romantic, time-honored Western principles that span the genre.

Bibliography:

Anderson, Lindsay. About John Ford. Plexus Publishing, 1999.

Bernstein, Matthew; Studlar, Gaylyn. John Ford Made Westerns: Filming the Legend in the Sound Era. Indiana University Press, 2001.

Bogdonovich, Peter. John Ford (Revised and Enlarged edition). University of California Press, 1978.

Braudy, Leo; Cohen, Marshall. Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Cowie, Peter. John Ford and the American West. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2004.

Eckstein, Arthur; Lehman, Peter (edited by). The Searchers: Essays and Reflections on John Ford’s Classic Western. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004.

Eyman, Scott. Print the Legend: The Life and Times of John Ford. New York: Simon & Schuster, c1999.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

McBride, Joseph. Searching for John Ford: A Life. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2003.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. New York: Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A.Wellman. New York: Atheneum, 1975.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review