Reader's Choice

Children of Men

By Brian Eggert |

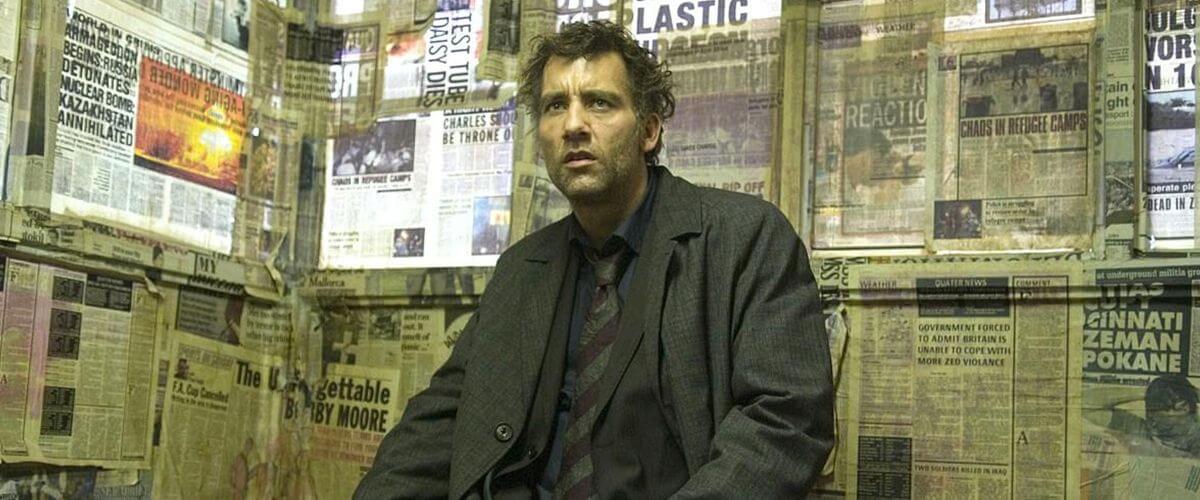

Children of Men’s opening scene skillfully establishes its high-concept world and how director Alfonso Cuarón will portray it. The year is 2027, and human beings have lost the ability to produce offspring. The last recorded newborn, known as “Baby Diego,” has just died at 18 years old. Broadcasters report the grim news on a television inside a London café on Fleet Street. Clive Owen’s character, Theo, walks unfazed among a crowd of onlookers grieving over the news. Cuarón and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki follow him outside in an unbroken shot, slowly panning across busy streets and buildings alive with vaguely familiar screens wrapped around their façades. An alcoholic, Theo stops to spike his coffee. Then an explosion goes off inside the café he just left. The handheld camera rushes toward the wreckage like a reporter on the scene. Amid the rubble, a victim clutches her detached arm. In a few brief seconds, Cuarón describes his film’s dystopia in terms that seem less like science fiction than a portrait of today. And while Children of Men employs realistic imagery and themes that mirror the contemporary, Cuarón’s literary symbolism transforms his aesthetic into a blend of the figurative and the grounded.

Loosely based on the novel by British author P.D. James, Children of Men is both a cautionary tale and an urgently authentic depiction of the not-too-distant future. The 2006 film expands on its 1992 source material to consider humanity’s anxieties about violent political disruptions, border politics, fear of Otherness, environmental decline, human infertility, and humanitarian crises the world over—all prescient issues in its immediate sociopolitical environment. Today’s Americans, of course, tend to think in terms of before and after the 9/11 attacks, but Cuarón shot in London just months after the bombings of July 7, 2005. However scarred by reality, both Cuarón and James offer the same, somewhat messianic solution of a mother and her miracle child as symbols of hope. Still, it’s less a glorious vision of the future seen in other examples of genre dystopias—such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) or Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), which delight in the out-there possibilities of technological advancement—than a grim summation of our reality. And yet, Cuarón, along with four credited screenwriters, weaves lofty references to art and religious iconography into the proceedings, aiming the allegorical potential of the genre at an unlikely, optimistic message.

Drained of color and bleakly ashen, Children of Men unfolds in the United Kingdom, one of the last few stable governments in the film’s world. With Baby Diego dead, humanity faces its last years. Refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants arrive in a mass exodus, fleeing their own crumbling countries. The British government targets them, focusing all political and military resources on containing them inside barbed-wire camps and cages. The police state’s propaganda machine warns to “Protect Britain. Report all illegal immigrants.” Or “To hire, feed, or shelter illegal immigrants is a crime.” Meanwhile, they issue government-sanctioned suicide kits to ease humanity’s slide into oblivion. Rebel groups conspire to seize control, and factions with names like “Repenters” and “Renouncers” divide society. Looters hide in the forests and attack passers-by. And as we learn later, the government attempts to create order by perpetrating random bombings and blaming them on rebels to stoke fear and foster administration support, capturing the real-life paranoid theories that the US government concocted 9/11 to gain additional control over the country. Even though the film bears signs of a dystopian genre exercise, it’s oddly familiar. Whether that says something about the film or our present situation is up to the viewer.

The film’s concept, too, might seem far-fetched until you consider recent science. Male sperm counts have declined by nearly 55 percent in the last 40 years. In a recent study about male fertility in the western world published in the journal Human Reproduction Update, researchers noted that human-made factors have led to hormone disruption and declining sperm counts. “Sperm count and other semen parameters have been plausibly associated with multiple environmental influences, including endocrine disrupting chemicals, pesticides, heat and lifestyle factors, including diet, stress, smoking and body-mass index,” wrote researchers from around the world. Sperm count rates will only continue to decrease, the report concluded. It’s undoubtedly a factor in the decline of U.S. birth rates as well, which according to a Brookings report, have decreased by 20 percent in just over ten years, dropping below “replacement fertility”—the rate needed to replace the current population. Along with immediate health factors, societal factors have impacted the declining birth rate as well. Quite simply, fewer women want to have babies or have chosen to delay childbirth until later in life. The combination of health and societal changes suggests that Children of Men isn’t so beyond the realm of reason.

The film’s concept, too, might seem far-fetched until you consider recent science. Male sperm counts have declined by nearly 55 percent in the last 40 years. In a recent study about male fertility in the western world published in the journal Human Reproduction Update, researchers noted that human-made factors have led to hormone disruption and declining sperm counts. “Sperm count and other semen parameters have been plausibly associated with multiple environmental influences, including endocrine disrupting chemicals, pesticides, heat and lifestyle factors, including diet, stress, smoking and body-mass index,” wrote researchers from around the world. Sperm count rates will only continue to decrease, the report concluded. It’s undoubtedly a factor in the decline of U.S. birth rates as well, which according to a Brookings report, have decreased by 20 percent in just over ten years, dropping below “replacement fertility”—the rate needed to replace the current population. Along with immediate health factors, societal factors have impacted the declining birth rate as well. Quite simply, fewer women want to have babies or have chosen to delay childbirth until later in life. The combination of health and societal changes suggests that Children of Men isn’t so beyond the realm of reason.

In a frighteningly familiar world, the story follows Owen’s alienated divorcé Theo Faron, a former idealist and activist turned disillusioned drunk. Theo, self-interested and without hope for humanity’s future—not to mention looking physically drained thanks to Owen’s downbeat screen presence—finds himself nabbed by the Fishes, a rebel group of anti-government, pro-refugee activists, led by his ex-wife, Julian (Julianne Moore). The former couple lost a child, causing their breakup and Theo’s utter lack of social motivation—a feeling concentrated and echoed by the state of the world. Still, there’s love between them. So Theo accepts a bribe and agrees to acquire transit papers from his connected cousin (Danny Huston), who runs an “Ark for the Arts” for the government, to help a young Black woman named Kee (Claire-Hope Ashitey) clear several refugee checkpoints and reach a boat. Soon enough, Julian’s fellow rebel Luke (Chiwetel Ejiofor) drives Theo, Julian, Kee, and her spiritualist caretaker Miriam (Pam Ferris) toward the boat rendezvous. After an attack that leaves Julian dead, Theo discovers not only that Kee is pregnant, carrying the first baby in 18 years and a symbol of hope for humanity, but that the Fishes orchestrated Julian’s death to seize the baby as a political device.

What’s strange about so many intense sequences in Children of Men is how buoyant they feel. This film steams ahead with the same momentum Cuarón brought to Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) and Gravity (2013). There’s even a bemused levity at times courtesy of an unlikely supporting role by Michael Caine. When Theo learns the Fishes killed Julian to wield the baby for their revolution, he escapes with Kee and Miriam to the secluded home of his friend, Caine’s Jasper, whom he visits in an earlier scene. Jasper’s few minutes of screentime give us a glimpse of Theo’s humanity and joy while also lending Caine the rare chance to play a pot-smoking hippie who makes fart jokes—and whose (badly Photoshopped) photos hint at Jasper’s once-prominent life as a political cartoonist. But in the film’s habit of turning every situation on its head, the Fishes locate Jasper’s home, where he distracts them as Theo and the others escape before meeting a grisly demise—the film’s most heartrending death, even more than Julian’s. Things move so fast that, like Theo, we barely have time to process their impact and consequence. It’s not until afterward when we’ve escaped the film’s gravitational pull that we can fully consider what we’ve seen. Call it riveting, entertaining, or enveloping—Children of Men is not a film that allows passive viewership.

For all its immediacy, Cuarón packs Children of Men with literary allusion and symbolism—much as he did in his 2001 breakthrough Y tu mamá también (2001) and Gravity. Consider Kee, whose name suggests with a homonym that she’s the solution to humanity’s predicament. Cuarón doubles down on her symbolic import when he frames the nude Kee similarly to Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus to reveal her pregnancy. And when it comes time to deliver her baby in a war zone, Theo sanitizes his hands with the last of his Scotch, a clear sign that he’s giving up his selfish lifestyle and returning to his former idealism. Pointedly, Theo must deliver Kee to a mysterious ship called Tomorrow, run by a group called the Human Project, no less. The stakes are unambiguous. Cuarón guides this reading with visual and aural references to Christian symbolism as well. For a film set to tinnitus tones that follow jarring explosions, there’s a surprising number of scenes in which choral vocals accompany emotional heights: Theo’s breakdown after Julian’s death, Theo’s reaction to Jasper’s death, Theo and Kee’s miraculous escapes. The angelic music creates an association between profound heights and Christian sentiment, contrasting the real-world aesthetic. The film’s symbology underscores our failure to procreate, representing how we have failed to create as God does, partly because our corrosive society has gone away from humanist, thus godly, ideals. Only when we return to those humanist, natural, and non-nationalistic ways will our hope for tomorrow return. It’s all obvious symbolism that, in another film, might seem embarrassingly overwrought. Somehow, perhaps because of the story’s binding energy, Cuarón’s obvious choices work.

For all its immediacy, Cuarón packs Children of Men with literary allusion and symbolism—much as he did in his 2001 breakthrough Y tu mamá también (2001) and Gravity. Consider Kee, whose name suggests with a homonym that she’s the solution to humanity’s predicament. Cuarón doubles down on her symbolic import when he frames the nude Kee similarly to Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus to reveal her pregnancy. And when it comes time to deliver her baby in a war zone, Theo sanitizes his hands with the last of his Scotch, a clear sign that he’s giving up his selfish lifestyle and returning to his former idealism. Pointedly, Theo must deliver Kee to a mysterious ship called Tomorrow, run by a group called the Human Project, no less. The stakes are unambiguous. Cuarón guides this reading with visual and aural references to Christian symbolism as well. For a film set to tinnitus tones that follow jarring explosions, there’s a surprising number of scenes in which choral vocals accompany emotional heights: Theo’s breakdown after Julian’s death, Theo’s reaction to Jasper’s death, Theo and Kee’s miraculous escapes. The angelic music creates an association between profound heights and Christian sentiment, contrasting the real-world aesthetic. The film’s symbology underscores our failure to procreate, representing how we have failed to create as God does, partly because our corrosive society has gone away from humanist, thus godly, ideals. Only when we return to those humanist, natural, and non-nationalistic ways will our hope for tomorrow return. It’s all obvious symbolism that, in another film, might seem embarrassingly overwrought. Somehow, perhaps because of the story’s binding energy, Cuarón’s obvious choices work.

Despite Cuarón’s poetic flourishes, he presents Children of Men with an eye toward verisimilitude in a shaky, really-there aesthetic. Cuarón and Lubezki capture the squalor of refugee camps, burning bodies, crumbling buildings, and rubble everywhere, shooting in extended takes as if following the live-on-location action like a fearless news crew to create an immersive mise-en-scène. The film renders large-scale destruction, bombings, and frightened people on the ground—all of which look familiar to anyone who has watched the news in the last thirty years. What is more, the film is a human project, like the name of the off-screen scientists trying to save humanity, shot from the perspective of human beings. Lubezki follows Theo, resisting the omnipotent or objective view that sci-fi stories usually occupy. Rather, every frame makes the viewer a participant, forcing us to consider how the events relate to our contemporary world. Cuarón told critic Jim Ridley that he wanted Children of Men to reveal how America has transformed from a land of immigrants to a land of isolationist zealots. Certainly, this is evident in the stateless Kee, who stands in for countless devalued immigrants, who are placed in refugee camps that evoke the Holocaust and are treated like subhumans. The association was powerful just five years after 9/11. Today it’s even more impactful when the US has separated over 20,000 migrant children from their parents and held them in detention camps across the country.

Cuarón’s aesthetic investigates our relationship with these images, usually watched from an apathetic and safe distance on the constant news cycle, which grinds down our resolve. He invests us in a character like Julian only to represent her sudden death in the car without dwelling on the moment, increasing its shock value. The tactic reminds us that the media’s eye isn’t always catching the full emotional weight or loss of the story. Cuarón’s brand of realism allows for moments of formal bravado as well. Film-savvy viewers who notice things like shot duration, and understand the difficulty Cuarón and his crew faced to achieve such shots, view Children of Men as a film blending gritty realism with a touch of the cinematic-fantastic. It’s impossible to watch the scene of Theo and Julian flirting in the car with a ping pong routine, where the camera maneuvers fluidly between the seats and passengers, and not feel a tickle of appreciation for the CGI-assisted feat. The same is true of the film’s famous extended shot inside the refugee camp, amid the chaos and shooting when seven specks of blood hit the handheld camera’s lens. The gradually disappearing drops remind us how long the shot continues through the action—even though the filmmakers achieved the illusion with several digitally assembled shots—until everything comes to a grinding halt. Theo emerges with Kee and her baby from a concrete shell of a building. Every soldier stops shooting; some drop to one knee and perform the sign of the cross. Theo, Kee, and the newborn move through them like Moses parting the sea.

Although there’s an overriding sense that Kee’s child will become the savior of humanity—the Human Project will surely research what makes the newborn special and may solve infertility—the story, told from Theo’s perspective as it is, robs Kee of her agency as a woman and diminishes her with its figurative use of her womb as a humanitarian symbol. Perhaps it’s Cuarón’s ironical and appropriately distended fictionalization that, in a patriarchal world constantly grappling with women’s rights over their bodies, Theo and not Kee remains central to the film’s conflict. Several forces attempt to gain control of Kee as a political weapon. Luke and his henchman Patric (Charlie Hunnam) hope to use Key’s unborn child as a symbol to convince others to join the Fishes’ cause. Miriam worries that if the British government gets ahold of the child, they will dispose of Kee and replace her with a “posh Black English lady as the mother.” The title accentuates this. Children remain the film’s subject, but as scholar Nicole Sparling notes, “the title’s metaphorical reference to humanity, in general”—the term Men standing in for humankind—represents a denial of “women’s agency as bearers of children.” Note also how Theo uses his final breaths to teach Kee how to care for her baby in the rowboat to Tomorrow. Even as the film comments on organizations who attempt to exploit Kee, the film never gives Kee much depth beyond a dramatic device in Theo’s redemption arc.

Although there’s an overriding sense that Kee’s child will become the savior of humanity—the Human Project will surely research what makes the newborn special and may solve infertility—the story, told from Theo’s perspective as it is, robs Kee of her agency as a woman and diminishes her with its figurative use of her womb as a humanitarian symbol. Perhaps it’s Cuarón’s ironical and appropriately distended fictionalization that, in a patriarchal world constantly grappling with women’s rights over their bodies, Theo and not Kee remains central to the film’s conflict. Several forces attempt to gain control of Kee as a political weapon. Luke and his henchman Patric (Charlie Hunnam) hope to use Key’s unborn child as a symbol to convince others to join the Fishes’ cause. Miriam worries that if the British government gets ahold of the child, they will dispose of Kee and replace her with a “posh Black English lady as the mother.” The title accentuates this. Children remain the film’s subject, but as scholar Nicole Sparling notes, “the title’s metaphorical reference to humanity, in general”—the term Men standing in for humankind—represents a denial of “women’s agency as bearers of children.” Note also how Theo uses his final breaths to teach Kee how to care for her baby in the rowboat to Tomorrow. Even as the film comments on organizations who attempt to exploit Kee, the film never gives Kee much depth beyond a dramatic device in Theo’s redemption arc.

When it opened in 2006, critics responded with apt enthusiasm. But the grim, high-concept story undoubtedly left general audiences cold to the Christmas Day release in the US. According to industry rumors, Universal didn’t believe in the project’s commercial potential, and sure enough, Children of Men failed to earn back its reported budget of $76 million. Even so, the film earned deserved awards, many places on critical year-end lists, and the Saturn Awards’ statue for Best Science Fiction Film. Never mind that Cuarón has claimed he did not intend to make a work of science fiction with Children of Men. Indeed, its setting in 2027 looks more like this moment, in the same way Brazil (1985) looks like futurology, but according to its director Terry Gilliam, it’s set right now. Cuarón wasn’t interested in another visionary work of science fiction like Blade Runner or Spielberg’s Minority Report (2002). He told his art department, “We’re not creating; we’re referencing.” He sought to pull from the real world instead of developing elaborate, new designs. The director supplied his team with images from Palestine, Iraq, Sri Lanka, and Chernobyl. He referenced America’s response to 9/11 with immigration panic, border control measures, wielding of the term “terrorist,” extraordinary rendition, and nationalistic symbols of security to serve political demand. Still, Children of Men remains vital because Cuarón’s entrenched allusions imbue the film with endless readability and interpretive potential.

The book’s author told critic Kenneth Turan that she sought to answer the question, “If there were no future, how would we behave?” The resulting text forces humanity to look in the mirror and see an ugly visage reflected back. Cuarón’s film does something similar, though the director seems more interested in presenting a hopeful alternative, despite the overriding unpleasantness of the setting. Children of Men’s world, not to mention our own, might require a true and other-worldly—and symbolically Christian—miracle to stop humanity from destroying itself, if you believe in that sort of thing. Then again, Cuarón’s fast-paced, kinetically shot dystopia emphasizes how our lives have been dominated by sociopolitical rhetoric that overshadows the fallout’s collateral damage and humanitarian crises. By the end, Children of Men is an achingly, almost dreamily optimistic film in the face of such brutally cynical conditions, offering a humanist message that neutralizes political debate. Sadly, the notion of a Black child uniting everyone from every side of the culture war, in which racism and white power play inextricable roles, seems like the most fantastical touch of all. Nevertheless, the film calls for uninvolved individuals to act, regardless of how despondent and hopeless we may feel given present-day conditions.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your support, Brenda!)

Bibliography:

Amago, Samuel. “Ethics, Aesthetics, and the Future in Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Children of Men.’” Discourse, vol. 32, no. 2, 2010, pp. 212–235. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41389843. Accessed 1 August 2021.

Kearney, Melissa S., and Phillip Levine. “Will births in the US rebound? Probably not.” Brookings. 24 May 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2021/05/24/will-births-in-the-us-rebound-probably-not/. Accessed 5 August 2021.

Levine, Hagai, et al. “Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis.” Human Reproduction Update, vol. 23, Issue 6, November-December 2017, Pages 646–659.

Rowin, Michael Joshua. Cinéaste, vol. 32, no. 2, 2007, pp. 60–61. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41690478. Accessed 1 August 2021.

Sparling, Nicole L. “Without a Conceivable Future: Figuring the Mother in Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, 2014, pp. 160–180. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5250/fronjwomestud.35.1.0160. Accessed 1 August 2021.

Wilson, Ricardo A. “In the Blind: Alfonso Cuarón and the Question of Futurity.” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 16, no. 2, 2016, pp. 151–182. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.14321/crnewcentrevi.16.2.0151. Accessed 1 August 2021.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review