Marty Supreme

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published on December 1, 2025. It has been re-posted in advance of its limited release on December 19.

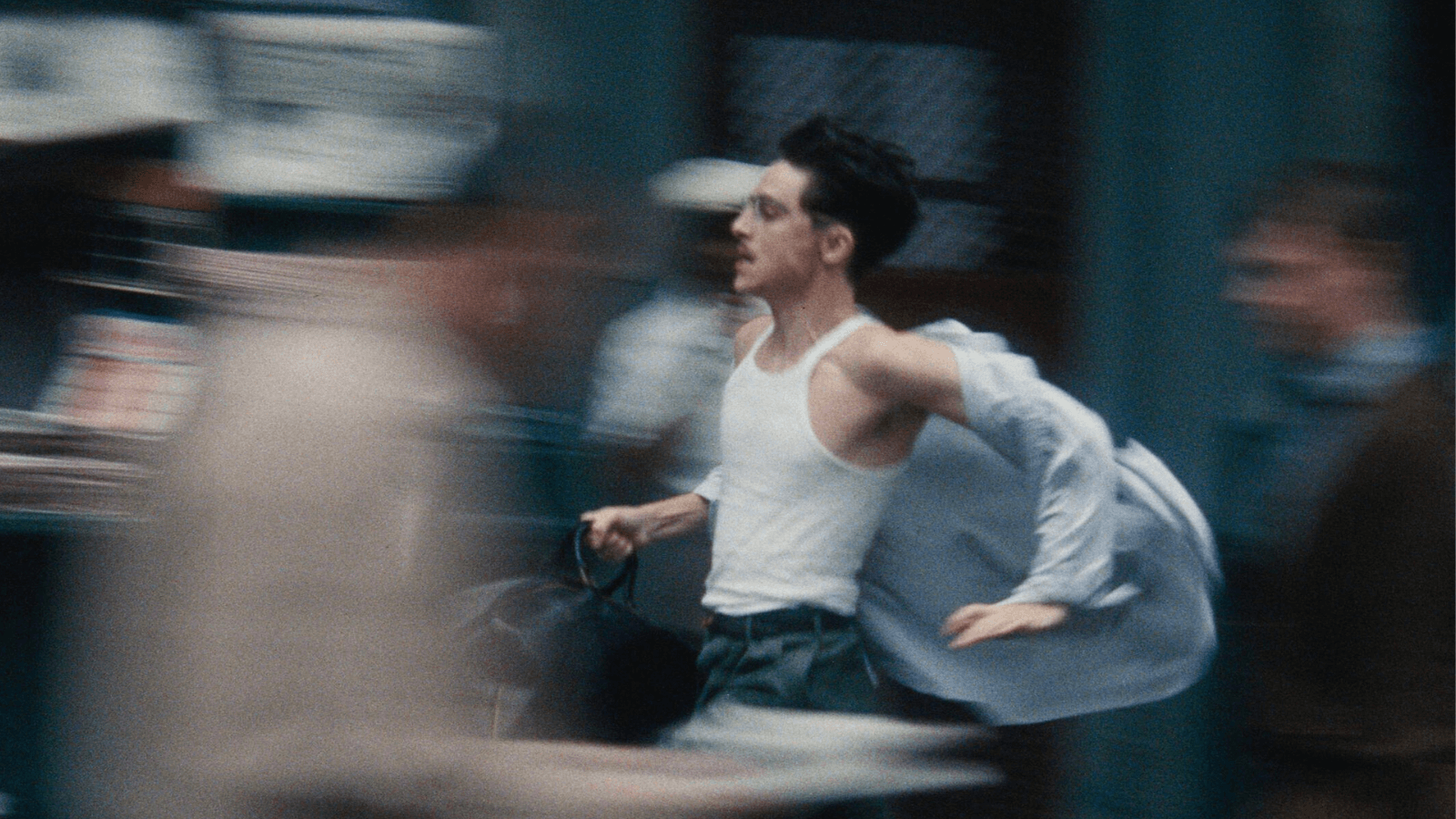

Marty Mauser knows he will become a world champion in table tennis. He’s so convinced of his inevitable victory that he persuades his friend, whose father is a successful businessman, to invest in branded ping-pong balls—not in the standard white, which he struggles to see when his opponents wear the same color shirt. His line will be orange “spheres,” stenciled with the words “Marty Supreme.” After much effort, including some world travel and various ill-conceived scams, he finally sees the first box. A moment later, they’re out the window, crashing onto the streets of New York. It’s a perfect encapsulation of Marty Supreme, about a character whose entire identity has been wrapped up in his desire for glory. Played by Timothée Chalamet in his finest performance to date, Marty is a symbol of the post-World War II drive for American greatness. Determined, cocksure, and convinced of his own superiority in the sport, Marty’s ambition runs on a full-tank mixture of delusion and pure skill. Watching his journey may cause adrenaline surges, gasps, and gripped armrests; it might also lead to a mild heart attack followed by tears and applause.

Although Josh Safdie has worked alongside his brother Benny on their last five projects, the siblings recently split to pursue separate careers. Curiously, their first solo efforts were both sports movies distributed by A24. Benny wrote, directed, and edited The Smashing Machine, released earlier this year, about MMA fighter Mark Kerr. With its Oscar-baity performances by Dwayne Johnson and Emily Blunt, the production too closely followed the 2002 HBO documentary of the same name, to the point where Benny directed dramatically re-enacted scenes from the earlier film. Marty Supreme benefits from the Safdies’ frequent co-writer and editor, Ronald Bronstein, who might be the secret weapon that defines the siblings’ relentless kineticism found in Good Time (2017) and Uncut Gems (2019). Whereas Benny’s solo effort felt different than the brothers’ earlier collaborations, Josh’s film—not his first solitary directing credit; that would be 2008’s The Pleasure of Being Robbed—maintains the Safdie signature momentum and nonstop, nerve-frying anxiety.

Josh Safdie has been planning Marty Supreme for several years. According to the press notes, his wife, Sara Rossein, an executive producer and the production’s researcher, found Jewish table tennis champion Marty Reisman’s 1974 autobiography, The Money Player: The Confessions of America’s Greatest Table Tennis Player and Hustler, in a bookstore bargain bin. Safdie read the book and was immediately fascinated by the 1950s table tennis scene in New York, where his uncle, who had instilled his interest in the sport at a young age, had encountered the underdogs and outcasts drawn to ping-pong. Players met in shady basements and smoky game halls, on the distant margins of the sports scene. Although table tennis attracted large crowds and devoted fans in Europe and Asia, it was far from mainstream in postwar America, drawing a cross-section of fanatics and oddballs who lost themselves in the fast-paced, high-intensity game. Rather than tell Reisman’s story, Safdie and Bronstein conceived a fictionalized version, Marty Mauser—an ambitious, overconfident hustler whose impulsiveness and bluntness prove magnetic, even as they land him in trouble.

Who better than Timothée Chalamet to play such a character? Chalamet—who declared, “I’m really in pursuit of greatness,” during his Best Actor acceptance speech for A Complete Unknown (2024) at the SAG Awards—feels aligned with Marty Mauser’s self-absorbed persona. And like his character, the actor’s ambition and ego are only matched by his sheer talent. For Marty, his talent makes the workaday world seem banal, like it’s holding him back. The film opens in 1952 on the Lower East Side, where Marty works at his uncle’s shoe store to pay the bills. Marty’s uncle hopes to promote him to a manager, a path Marty equates with a death sentence. Instead, Marty plans to win the World Table Tennis Championships, which will be held in the UK. After that, he’s convinced his win will popularize the sport in the United States and land him on a Wheaties box. However, he’s constantly held back from his dream by the world’s pesky realities. Similar to Good Time and Uncut Gems, a maddening series of practical obstacles and personal disasters waylay the protagonist’s ultimate goal.

Not only does Marty want to escape his job, but he must contend with his disapproving mother (Fran Drescher), his married girlfriend Rachel (Odessa A’zion), who wants to escape with him, Rachel’s abusive husband (Emory Cohen), and finding enough cash for his initial trip. When his uncle attempts to sabotage his dream by withholding the back pay Marty needs for the flight, Marty holds his coworker at gunpoint until he collects what he’s owed. Marty is constantly defending his dreams with chaotic choices, fighting to prove himself to people who don’t believe in him or understand his dream. Once overseas, he faces off against a steely Japanese opponent, Koto Endo, a deaf player whose peculiar racket style leaves Marty confounded and reeling from a devastating loss. Koto Kawaguchi, an actual table tennis pro and winner of the Japanese National Deaf Table Tennis Championships, plays Endo in a role that becomes more than his stone-faced first appearance. Afterward, Marty reluctantly agrees to an international tour with the Harlem Globetrotters, playing a goofy ping-pong routine during halftime shows alongside his friend, the former table tennis champ Bela (Géza Röhrig)—who shares an unthinkable, yet strangely beautiful story about how he helped others survive in a concentration camp during the Holocaust.

Behind his wire-framed glasses, lean physique, thin mustache, acne scarring, and unibrow, Marty doesn’t look intimidating. But with a sharp wit, he talks as fast as he plays. Yet his colossal ego often elicits incredulous reactions. He tells a table of reporters that he’s “The ultimate product of Hitler’s defeat” and evokes the bombing of Japan more than once. The character reminds me of Chalamet’s Lee from Bones and All (2022), who remarks, “If you weigh 140 pounds wet, you got to have an attitude—a big attitude.” Marty takes it even further. He’s just plain brash and impulsive. When he sees former Hollywood starlet Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow), who has retired into the life of a socialite alongside her pen-industry mogul Milton Rockwell (Kevin O’Leary, Canadian politician and businessman), he makes a bold pass. Stone and Rockwell will become regular fixtures in Marty’s journey, with the former an occasional lover and the latter a potential backer for the player’s rematch against Endo.

Marty Supreme takes off when the character returns to New York for a brief stop before he plans to visit Tokyo to face off against Endo. Except that he has no plan, only angles he can work. In a chapter reminiscent of Martin Scorsese’s The Color of Money (1986), he talks his way into getting some quick cash with his cabdriver friend, Wally (Tyler Okonma, aka Tyler the Creator), a fellow hustler who helps Marty hoodwink some rough customers at a bowling alley in the boonies. Another plan involves recovering a dog owned by a vicious gangster (director Abel Ferrara, intimidating as hell). Enlisting Rachel to help, they attempt to collect reward money for the dog they lost, but their scheme leaves several people dead. No matter. Elsewhere, Marty tries to steal jewelry from Kay, only for her to promise him a diamond necklace, a pledge he struggles to collect on. As for Rockwell, Marty insults him one too many times by dismissing the death of his son, who died in World War II, requiring him to grovel—and worse—for a handout. Safdie’s propulsive whirlwind leaps from one maneuver to the next, fueled by Marty’s desperate need to prove himself.

An early scene finds Marty and Rachel having sex in the inventory room at his uncle’s shoe store. The moment gives way to the title sequence, set against a realistic-looking animation of his sperm inseminating one of her eggs, set to Alphaville’s “Forever Young”—opening credits amusingly reminiscent of the sequence in Look Who’s Talking (1989), which was set to “I Get Around” by The Beach Boys. There’s a lot of 1980s-ness throughout Marty Supreme, regardless of the 1950s setting. The soundtrack features wall-to-wall ’80s hits, from Tears for Fears’ “Everybody Wants To Rule The World” to New Order’s “The Perfect Kiss.” Daniel Lopatin’s score, too, has a synth vibe that recalls the more psychedelic passages from his music for Good Time and Uncut Gems. Safdie no doubt chose music from this decade to underscore Marty’s unrelenting need for success, high performance, and personal ambition, which Reagan-era America often portrayed as glamorous. Themes of winning and becoming “the best” dominated the culture, especially sports movies, with underdog stories such as The Karate Kid (1984), multiple Rocky sequels, and Major League (1989). To be sure, the film that came to mind most while watching Marty Supreme was Bloodsport (1988), since both involve a cocky American who, while evading authorities, travels to Asia to defeat the resident champion.

Shot on location in the Lower East Side, where many of the buildings from the film’s era still stand, the film also doubles as a portrait of a bygone era in New York history, evoking the past with the same visual immersion as Joan Micklin Silver’s Hester Street (1975) and Woody Allen’s Radio Days (1987), soundtrack notwithstanding. Working alongside production designer Jack Fisk—a legend who has worked with Scorsese, Terrence Malick, Brian De Palma, David Lynch, and Paul Thomas Anderson—Safdie also creates a convincing portrait of place and time on detailed soundstages. There’s never a moment where the viewer must suspend disbelief or feels taken out of the picture by shoddy CGI, even during the table tennis matches, where the ball is surely digital. Rather, Safdie and cinematographer Darius Khondji use 35mm celluloid with old-school anamorphic lenses, rendering a credible verisimilitude in rusty browns and textured images throughout. Safdie and Bronstein’s nimble editing propels the 149-minute feature at such a speed that it feels like a taut 90 minutes.

Chalamet disappears into this world, shedding his usual persona for a tough exterior, hardened by his life in New York and the pervasive disinterest in his passion. It’s a performance driven by Marty’s instinctive hunger and not-unjustified faith in his talent. But there’s more than just Marty’s electric pride. Safdie and Bronstein’s script grounds the character by the finale, giving Marty more room to grow than Robert Pattinson’s crook in Good Time or Adam Sandler’s gambling addict in Uncut Gems. By the end, the film becomes a kind of coming-of-age story, with a full-circle moment that calls back to the title sequence. It’s an overpowering emotional release, with Chalamet evoking his own final scene in Call Me by Your Name (2017), along with Tom Hanks’ outpouring in the last moments of Captain Phillips (2013). Few of Safdie’s characters ever redeem themselves. And while Marty’s manipulation of people risks him becoming irrecoverably awful—he tells Rachel at one point, “I have a purpose. You don’t.”—Chalamet gives an outstanding performance that can’t help but compel the viewer to cheer for him after he’s learned some hard lessons.

Marty Supreme is the best film of Josh Safdie’s oeuvre and contains a performance that will elevate Chalamet’s short but impressive career to the greatness he so desires. Like many of Safdie’s previous films with his brother, it’s a story with a punishing momentum that leaves the viewer feeling like they just sprinted five miles straight. It’s impossible to view passively; the film is a physical experience. One must writhe in their seat, cover their eyes, laugh out loud, and fight for breath. And while Safdie has told stories about dreamers before, they’ve mostly been doomed by their own compulsions and recklessness. However, with Marty’s conditional victory, his story feels oddly crowd-pleasing in its blending of New York street life volatility and ’80s sports movie schematics, as though Scorsese had turned Mean Streets (1973) into a scrappy yarn about jocks trying to escape their limited neighborhood. Believing it’s “every man for himself,” Marty is the embodiment of the American Dream, with all the self-obsession, moral corruption, capitalist back-dealing, and dynamism that description entails. It’s exhilarating, stressful, oddly uplifting, and unquestionably one of the best films of 2025.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review