A House of Dynamite

By Brian Eggert |

In case the world today wasn’t already fraying your nerves, I submit to you Kathryn Bigelow’s anxiety-inducing A House of Dynamite—a horrific what-if scenario that demonstrates the thin thread holding the fabric of our world together, preventing world powers from engaging in a devastating nuclear war. With chilling realism, the Netflix production details a plausible series of events that bring the United States to the brink. It’s designed to show how we place our trust in flawed leaders, faulty technologies, and best guesses rather than unshakable, ironclad security. Politicians and military leaders reassure citizens that America is the strongest nation in the world, with a military might that no other power can match. But Bigelow’s film shows how every safeguard and every official in this carefully constructed system of checks and balances are terrifyingly fallible, and our sense of safety is an illusion that could fizzle out at any moment. All it takes is the wrong set of circumstances to reveal how quickly our foundations will crumble.

The film was written by Noah Oppenheim, a former television producer whose previous work as a dramatic writer includes Pablo Larraín’s Jackie (2016) and this year’s Netflix limited series Zero Day, about a devastating cyberattack on the US. A House of Dynamite unfolds like a three-part series, featuring a trio of overlapping sections that examine the situation from multiple perspectives. This is not to achieve a Rashomon-style investigation of subjective memory; instead, it’s to break down a roughly 20-minute doomsday countdown from various angles in something approaching real time. The situation is this: An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launched from an unknown location on the other side of the planet races toward the US and, unless stopped, will strike Chicago and kill about ten million people in the initial blast alone. A failed satellite reading means the attacker remains unknown, so it’s unclear if this is the first blow in a larger assault or some kind of test of America’s response.

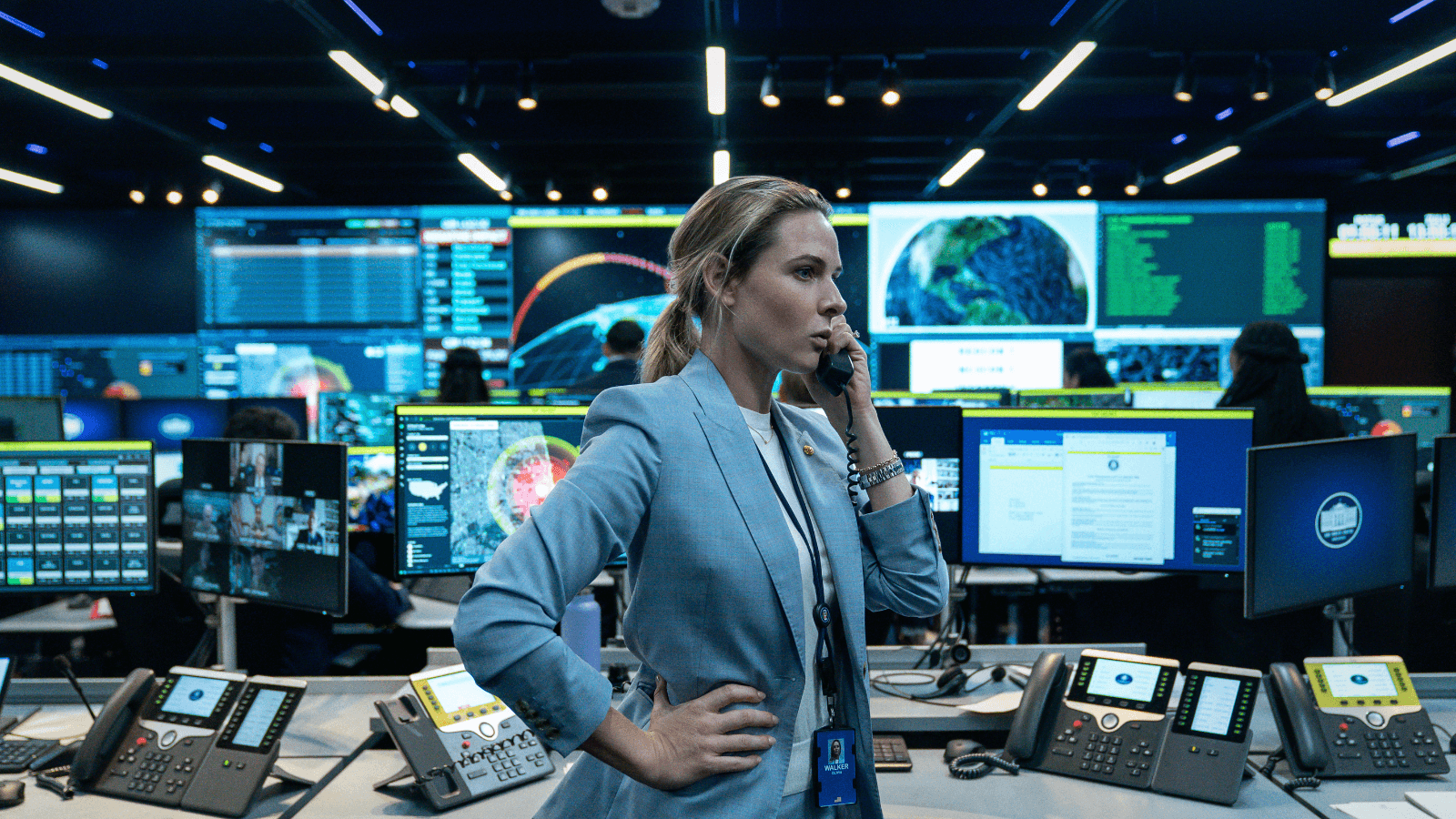

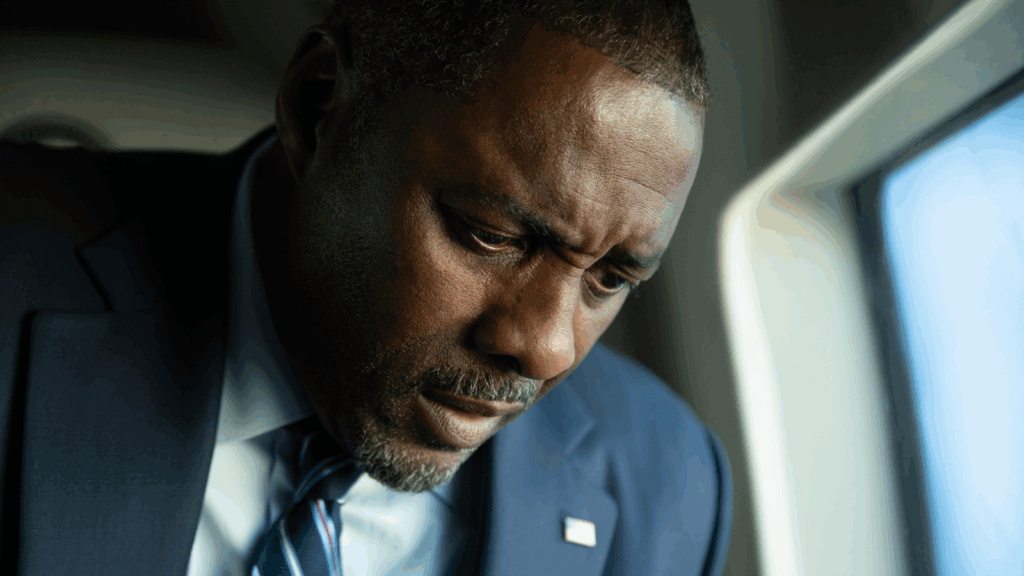

Bigelow thrusts the viewer into the many locations across the US responsible for stopping the missile, inundating us with an alphabet soup of departments and acronyms. The Missile Battalion in Alaska, headed by Maj. Gonzales (Anthony Ramos), deploys a Ground-Based Interceptor (GBI) to stop the nuke, but this is like “hitting a bullet with a bullet.” Captain Walker (Rebecca Ferguson) runs the White House Situation Room that organizes the heads of state who will manage the crisis, even while worrying about her husband and young boy. General Brady (Tracy Letts) runs the United States Strategic Command (STRATCOM), but he seems more concerned about last night’s game. Secretary of Defense Reid Baker (Jared Harris) runs the Pentagon, and he’s preoccupied with his daughter (Kaitlyn Dever), who lives in Chicago. The Deputy National Security Advisor (Gabriel Bosso) shares the bad news that the POTUS (Idris Elba) has two options: “Surrender or suicide.”

Why only these choices? Because if the US doesn’t respond to the Chicago attack, then its leadership appears weak to its enemies. But any counterattack would be uninformed, given the missile’s unknown origin. Still, if this is indeed a nuclear war, then perhaps America should strike down all of its enemies to preempt further attacks, a decision that would mean obliterating Russia, Iran, North Korea, and China. While the characters debate how to respond, Oppenheim’s script offers scant character development, leaving the star power of actors such as Elba, Ferguson, and Harris to lend them personality. The film has little time for emotional scenes, aside from a few poignant moments where people call their loved ones, perhaps for the last time. By the open-ended conclusion, A House of Dynamite feels like an undercooked version of Sidney Lumet’s excellent Fail Safe (1964), which explored similar circumstances and with far more disturbing results.

Bigelow shoots in a mode of faux realism that she’s been using since The Hurt Locker (2009), the film that earned her the first-ever Oscar for Best Director given to a woman. With Zero Dark Thirty (2012) and her most recent effort, Detroit (2017), Bigelow has maintained a hyper-kinetic style of shaky-cam aesthetics, here captured by cinematographer Barry Ackroyd, who has developed this look with filmmakers such as Ken Loach and Paul Greengrass. Editor Kirk Baxter delivers a choppy presentation, filled with too many establishing shots in Washington, D.C. and montages of vehicles moving from one secure location to another—all set to a banal score of booming tones by Volker Bertelmann. Spending more time on characters may have provided viewers with more to engage with than just the situation itself. And even while the production is solidly presented, I yearn for Bigelow to move on from her military and political obsession and once again engage in genre fare. I miss the Bigelow who made Near Dark (1987), Point Break (1991), and Strange Days (1995).

Of course, we must consider what it means to watch a movie like A House of Dynamite in 2025, when the current administration no longer resembles or behaves like traditional American leadership. It’s almost surreal to see a diverse cast of political players acting intelligently in a grave situation, as opposed to a group of witless dopes behaving with pompous showboating, undiplomatic posturing, and outright stupidity. A House of Dynamite is even more frightening when one considers how these events would play out today. By presenting a seemingly normal version of America, the film inevitably feels like an artifact next to a country that is now behaving in far from ordinary ways. When Elba’s POTUS remarks, “This is insanity,” General Brady replies, “No, sir. This is reality.” But it doesn’t feel like our reality. Reality is far more terrifying. At least the leadership in the movie makes informed decisions based on facts and intelligence. If A House of Dynamite is reminiscent of Fail Safe, we seem to be living in the frighteningly, almost comically ignorant alternative version from Stanley Kubrick’s satirical Dr. Strangelove (1964).

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review