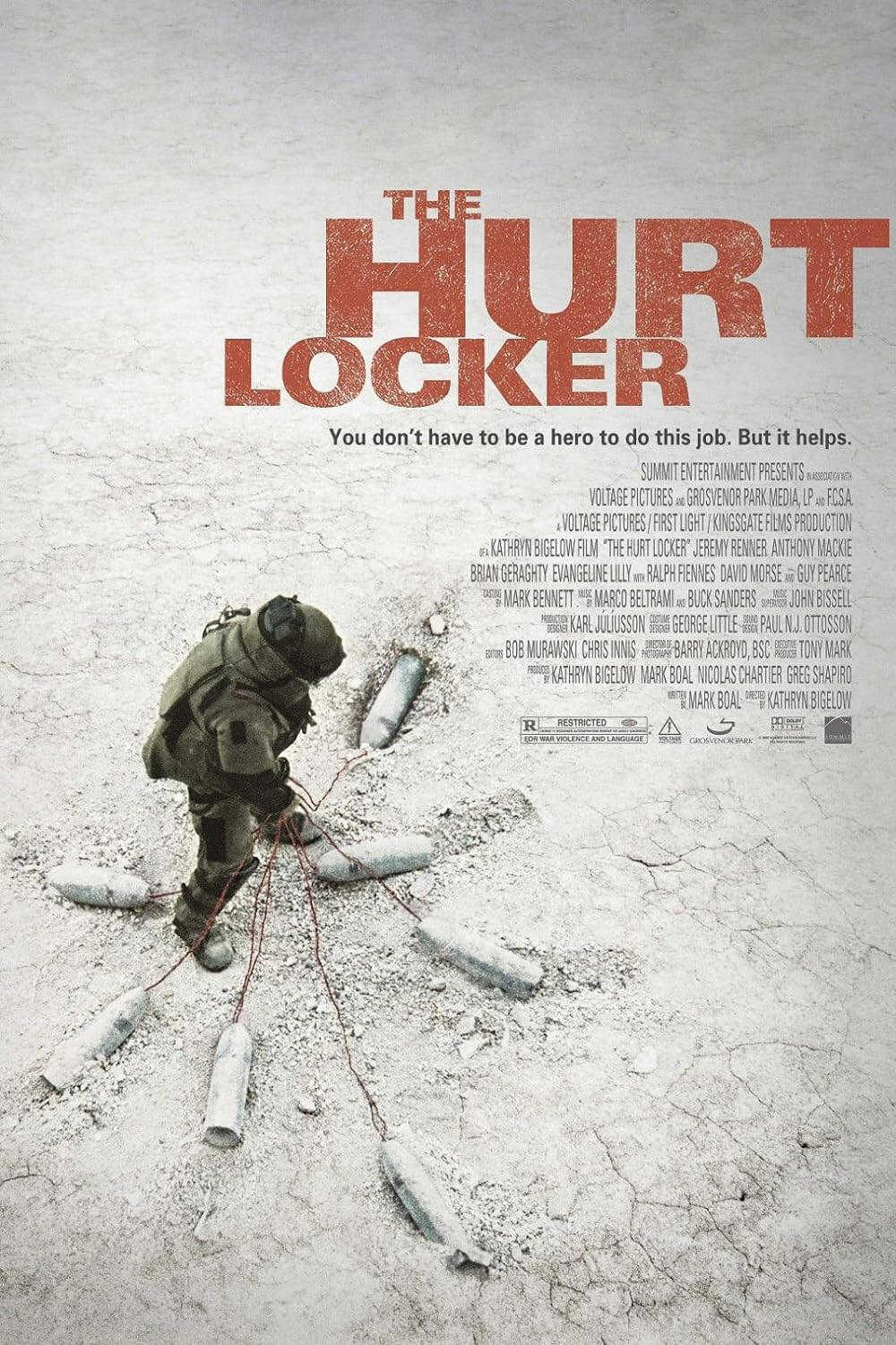

The Hurt Locker

By Brian Eggert |

Kathryn Bigelow’s latest film The Hurt Locker, despite being an actioner set in Iraq sometime in 2004, doesn’t use its setting for a political commentary. Instead, it brushes away time and place to examine the truth of war, something that repeats with every worldly conflict because human nature itself is repetitive. More enduring than your typical war movie, Bigelow has constructed a suspenseful and confident motion picture about addiction, filled with biting observations about why some go to war, and then why some stay. The opening titles read, “The rush of battle is often a potent and lethal addiction, for war is a drug.” This repeats a theme that’s brought up in Bigelow’s work over and over again, namely addiction to violence in its various forms, each in a unique and stimulating way: Like blood-sucking in her vampire yarn Near Dark, virtual reality in Strange Days, or adrenaline rushes in Point Break, war presents a thrill that, for the film’s protagonist, cannot be matched by any alternative.

Jeremy Renner plays Staff Sgt. William James, a tech who has disabled nearly 900 explosive devices. He’s skilled but labeled insane, suicidal, and just plain stupid for rushing into his missions without care for protocol or safety precautions. A counter reminds us that James has only 38 days left in Bravo Company, and while another soldier in his position might lessen the risk for themselves in those final days, James seems to propel himself even further into the fire. Forget the recon droids used to remotely scout ahead and assess the situation; James walks into danger with his head up as if invincible. But that thick padding and armor used to shield him from an inevitable blast only protects at a certain range, and James’ job always places him inside that range.

The others on his team, Sgt. Sanborn (Anthony Mackie) and Specialist Eldridge (Brian Geraghty), consider James reckless and irresponsible. Indeed, he places them in unnecessary harm more than once in the film. Perhaps James’ unbridled heroism forces him to dash headlong into danger no matter the risk. Perhaps disarming something that at any moment could kill him keeps him going, and that rush serves as an addiction. Whatever the reason, it’s clear James needs what he does as much as his company needs him.

At any moment, one of these characters could explode, though not enough about them is communicated to really involve the viewer beyond raw suspense. Comparable to Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear, we’re perpetually waiting for the detonation that will blow a character to smithereens, except Bigelow doesn’t provide clear-cut motivations as to why James puts himself in this danger, just a text that needs reading and interpretation to grasp. Unlike Clouzot’s film, where the characters drive hundreds of gallons of nitroglycerin across a rugged landscape out of desperation, James does his work voluntarily. Why does he do it? Quiet and enigmatic, James keeps himself at a distance. But among the notable faces in the film’s cast (Guy Pearce, Ralph Fiennes, and David Morse each make cameo appearances), Renner’s is the most perceptibly human, yet inscrutable, and so he remains a fascinating study.

Written by journalist Mark Boal, whose first-hand experiences in Baghdad were translated into this fictionalized account, the film contains a gripping realism supported by Bigelow’s kinetic presentation. Utilizing four handheld cameras, cinematographer Barry Ackroyd (United 93) employs a scattered style that’s unoriginal today, but effective here when capturing the chaotic mentality of someone who jumps into life-and-death situations all day, every day. Covered with dust, sweat, and grit, Bigelow’s stage has an undeniably authentic tone, allowing our attention to focus on the human drama unfolding before us.

Movies about the Iraq conflict have ranged from actionized to sermonizing, from The Kingdom to Stop-Loss and everything in between. Some stand on a soapbox and don’t step down for the duration, like Lions for Lambs, whereas Redacted took an utterly brutal glimpse of the conditions over there, condemning the entire endeavor with an unsympathetic and critical eye. Others are incredibly sensitive toward the ordeal, such as In the Valley of Elah, which considers the effect of war on the individual, just like Bigelow’s does.

The Hurt Locker refuses to lecture, in the same way that Stanley Kubrick’s war films Paths of Glory and Full Metal Jacket concerned themselves with the effect of war on humanity more than the wars themselves. That the events within take place in Iraq are inconsequential; the same story could be told anywhere. It comes down to James’ self-destructive need, his addiction to creating an unfathomably tense atmosphere around himself, and then literally defusing that tension. After that, it’s only a matter of repeating the singularity of that moment, again and again, to feel alive. Through the madness and constancy of such repetition, Bigelow makes the most fearless and exhausting film of her career.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review