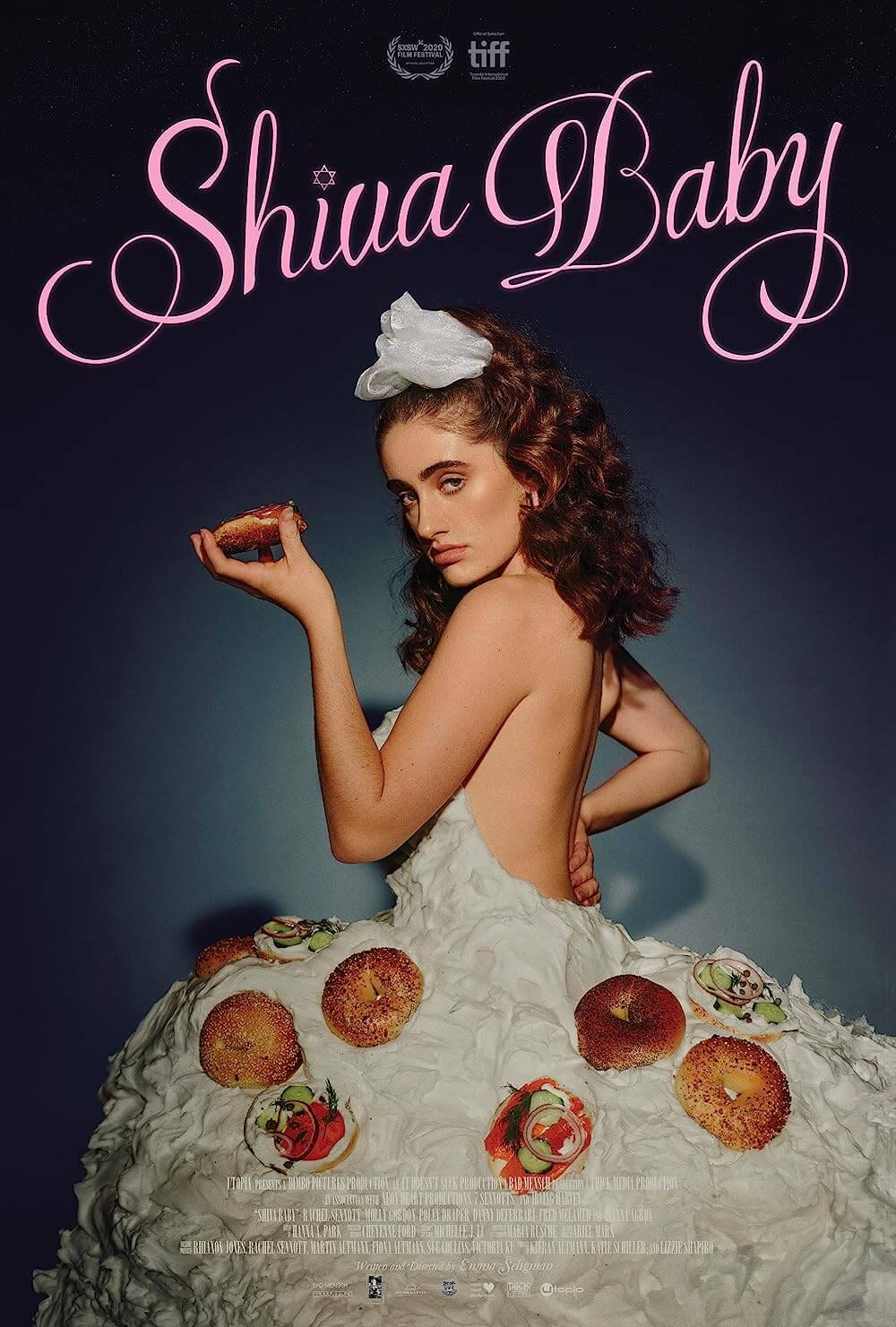

Shiva Baby

By Brian Eggert |

Emma Seligman’s debut feature Shiva Baby runs a mercifully short 78 minutes. Any longer, and it may have caused a heart attack. The writer-director’s expansion of her same-named short film is riddled with anxiety. The second-hand embarrassment is palpable, causing us to squirm in our seats, gasp in horror, or broadcast more than one audible “oh no” at the screen. Cringe comedy isn’t an unpleasant enough term, given how expertly Seligman manipulates the viewer into the rattled, sweaty, palpitating frame of mind of her central character, Danielle, played by Rachel Sennott. When the film opens, Danielle finishes hooking up with her sugar daddy and leaves for a shiva, though she’s unsure who died and missed the funeral for her sex work. But even before her recent patron, Max (Danny Deferrari), arrives at the same shiva and makes an already unbearable family situation worse, the single-setting film becomes achingly tense and uncomfortably funny.

Seligman’s treatment of Danielle’s sex work is honest and humanizing, placing us on the protagonist’s side in the first shot when Max almost forgets to pay, and then sends Danielle off with a lingering, inappropriately intimate hug. Whereas other films either demonize sex workers or portray them with hearts of gold, Seligman accepts the occupation matter-of-factly. Those close to Danielle, however, aren’t so accepting when they uncover her secret. The next scene finds Danielle with her parents, who have just arrived outside the shiva. Her mother Debbie (Polly Draper), a fussy and brutally honest woman, observes that Danielle has lost weight and looks “like Gwyneth Paltrow on food stamps.” Her father, Joel (Fred Melamed), a dopey and oblivious sort, shares a humiliating story with others in attendance about Danielle’s crushing prom experience as though it were an amusing anecdote. Once they’re inside, her oversharing parents escalate every minute into a trainwreck.

Frazzled, Danielle answers an onslaught of questions from her extended family and friends. Are you still in school? What are your career plans? Are you seeing anyone? Her answers vary out of shame and uncertainty. She tells people that she babysits for money, has nothing serious in the boyfriend department, and is going to school to learn the “lens” of feminism. They compare her life progress to the more straightforward track of Maya (Molly Gordon), a family friend who’s in law school and who also happens to be Danielle’s ex—her bisexuality is a family secret that Debbie wants to keep that way. Then, as Danielle frantically tries to keep out of Maya’s view while navigating the prying questions about her life and remarks about her slim physique, the frame captures a familiar silhouette out of focus in the background. It is Max, who arrives a few minutes before his wife, Kim (Dianna Agron), whom Danielle did not know about. Nor did she know that Max has a newborn, which the couple rudely brought to the service, and which seems to insinuate itself into every conversation with its endless wailing.

Sound plays a crucial role in Shiva Baby, from the baby’s persistent bawling to the composer Ariel Marx’s score of erratically plucked strings—reminiscent of an intense Chinese zither. The sound design has been tuned up, heightening the volume of invasive voices around Danielle, amplifying the perceived assault on her senses. Cinematographer Maria Rusche resists exaggerating the visual stress with wide-angle lenses or shaky camerawork until a delirious, borderline surreal sequence of tunnel vision. Every face becomes grotesque to Danielle. She sees them woofing down smoked salmon on cream cheese bagels, reflecting her own suppressed desire to eat; she sees them laughing monstrously in slow-motion; she sees eyes regarding her with suspicion. Editor Hanna A. Park also creates nervy micro-crises with clever cuts. Note the scene when someone at the crowded service bumps into Danielle and leaves her thigh bleeding and her nylons torn. Other quick disasters occur, such as when someone spills coffee on her white shirt or asks her to clean up Max’s baby’s vomit. The film is a progression of mishaps.

Sound plays a crucial role in Shiva Baby, from the baby’s persistent bawling to the composer Ariel Marx’s score of erratically plucked strings—reminiscent of an intense Chinese zither. The sound design has been tuned up, heightening the volume of invasive voices around Danielle, amplifying the perceived assault on her senses. Cinematographer Maria Rusche resists exaggerating the visual stress with wide-angle lenses or shaky camerawork until a delirious, borderline surreal sequence of tunnel vision. Every face becomes grotesque to Danielle. She sees them woofing down smoked salmon on cream cheese bagels, reflecting her own suppressed desire to eat; she sees them laughing monstrously in slow-motion; she sees eyes regarding her with suspicion. Editor Hanna A. Park also creates nervy micro-crises with clever cuts. Note the scene when someone at the crowded service bumps into Danielle and leaves her thigh bleeding and her nylons torn. Other quick disasters occur, such as when someone spills coffee on her white shirt or asks her to clean up Max’s baby’s vomit. The film is a progression of mishaps.

Although luck isn’t on Danielle’s side in Shiva Baby, she’s not an innocent victim of misfortune. Somewhere between her self-absorption, dishonesty, and debasement, she has brought some—but not all—of this misery upon herself. To cover up her directionless life, she lies and sets herself up for a subsequent debacle when she’s exposed. Predictably, her fib about babysitting opens the door to someone suggesting that she watch Max’s child, an already awkward proposition made worse when she turns it down. Only those closest to her recognize that something is going on between Danielle and Max, but she tends to push away those who are close to her. When her character isn’t engaging in self-sabotage, Sennott offers several genuinely hilarious moments of performative politeness and rudeness, particularly in her loaded exchanges with Maya or her mother. They ask, “Are you okay? You’re behaving strangely.” But, of course, these questions never help someone feel calm or normal. Danielle responds with a false smile or overblown sarcasm to disguise her apparent state of catastrophe.

Seligman’s calibration of the film’s comic tone impresses; her direction would be commendable for a seasoned filmmaker and it’s much more so for a debut. Shiva Baby is efficient and unwavering, exhaustingly so. Every detail further encloses Danielle in her chaotic perspective, from the modest interiors to the forced niceties required by the situation—those moments that demand patience, as when an elderly lady needs help to her car, or when a strange man attempts to confirm whether the bathroom has a fan or a window. This disorienting humor, combined with Sennott’s brilliantly timed performance, recalls the organized chaos of David O. Russell’s comedies like Flirting with Disaster (1996), I Heart Huckabees (2004), and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). In that way, it’s a stressful yet affecting film of memorable highs and lows, and it signals the arrival of an exciting new filmmaker whose next project can’t come soon enough.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review