Origin

2.5 Stars- Director

- Ava DuVernay

- Cast

- Aunjanue Ellis, Jon Bernthal, Vera Farmiga, Audra McDonald, Niecy Nash-Betts, Nick Offerman, Blair Underwood, Finn Wittrock, Connie Nielsen

- Rated

- PG-13

- Runtime

- 135 min.

- Release Date

- 12/08/2023

A curiously scholarly drama, Origin is Ava DuVernay’s exploration of Isabel Wilkerson and her journey to diagnose systemic injustice across history and various cultures. Filled with compelling arguments, heartfelt speeches, and lessons about the past, the film draws inspiration and insight from Wilkerson’s 2020 best-selling nonfiction book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. While Wilkerson grapples with crises in her personal life, she posits that racism is an inadequate description of the systemic oppression of people, with examples ranging from Jews in Nazi Germany to anti-Black violence in America to India’s social hierarchy. However distinct these cultural problems, which she considers at length, they share similar modes of dehumanization and even, disturbingly, draw inspiration from one another. The theories propelling DuVernay’s film are intellectually intriguing and demand consideration, but the concepts resonate more than the characters, leaving Origin to feel like an ungainly marriage between narrative fiction and documentary.

Origin is familiar territory for DuVernay, whose work often asks confronting questions and reveals troubling realities about racism in America. She made a traditional period drama with Selma (2014), which looked at Martin Luther King, Jr. through the lens of the 1965 march to Montgomery for voting rights. With 13th (2016), her part-exposé, part-history lesson documentary, she details how the US prison industrial complex links incarceration with slavery. Her latest film blends the two formats of drama and documentary, giving what feels like three-fifths of the runtime to the latter, making the drama feel underserviced. While DuVernay’s screenplay gets to the root of Wilkerson’s arguments, it often sidesteps the characters in favor of exploring the author’s thesis. Then again, the evidence builds to such a convincing way of understanding how prejudice and power function, that the film engages the way a particularly interesting university lecture would.

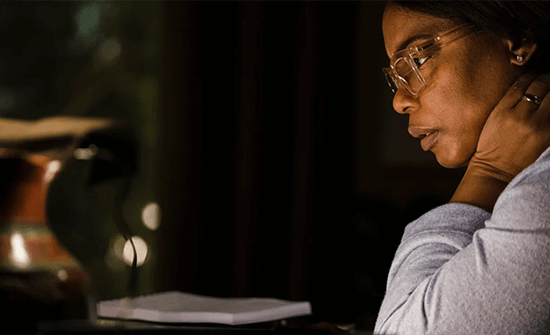

In a harrowing performance, Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor plays Wilkerson, the first Black woman to receive the Pulitzer Prize. After a former editor (Blair Underwood) encourages her to write about the killing of Black teen Trayvon Martin in 2012, Wilkerson questions the response to Martin’s death and finds inspiration to investigate racism as a product of caste systems. While her initially hazy thesis materializes in her mind, she organizes care for her ailing mother (Emily Yancy), who must enter a senior facility. Wilkerson’s mother believes Martin—who was shot walking around his father’s neighborhood at night—should have been more careful not to look suspicious in a predominantly white gated community. But Wilkerson, supported by her loving husband (Jon Bernthal), argues that people shouldn’t have to live their lives that way, protecting themselves from racists. The question remains: Do you live according to how things should be or how they are?

While recovering from sudden tragedies in her life—one of them confusingly unexplained—Wilkerson pours herself into her book project, despite skepticism about the complex nature of her theory. During a visit to Germany, where she attempts to link the Holocaust with American slavery, her arguments fail to convince a local intellectual (Connie Nielsen). Wilkerson’s further research crystallizes her ideas, and DuVernay shows her evidence through flashbacks and visualizations. Among the most fascinating entails anthropologists Allison Davis and Burleigh B. Gardner going undercover in the Jim Crow South and producing the 1947 book Deep South: A Social Anthropological Study of Caste and Class. Another details a German worker, August Landmesser (Finn Wittrock), who, in a famous 1936 photo, refused to perform a Nazi salute out of solidarity with his Jewish wife. Most eye-opening is a real-life meeting where Nazi leaders use America’s Jim Crow laws to inform policies that shaped the Holocaust.

While recovering from sudden tragedies in her life—one of them confusingly unexplained—Wilkerson pours herself into her book project, despite skepticism about the complex nature of her theory. During a visit to Germany, where she attempts to link the Holocaust with American slavery, her arguments fail to convince a local intellectual (Connie Nielsen). Wilkerson’s further research crystallizes her ideas, and DuVernay shows her evidence through flashbacks and visualizations. Among the most fascinating entails anthropologists Allison Davis and Burleigh B. Gardner going undercover in the Jim Crow South and producing the 1947 book Deep South: A Social Anthropological Study of Caste and Class. Another details a German worker, August Landmesser (Finn Wittrock), who, in a famous 1936 photo, refused to perform a Nazi salute out of solidarity with his Jewish wife. Most eye-opening is a real-life meeting where Nazi leaders use America’s Jim Crow laws to inform policies that shaped the Holocaust.

Origin is a film of many textures and historical events, each rendered with care by DuVernay and cinematographer Matthew J. Lloyd. The present-day scenes look grainy and natural, often conveying an emotional immediacy from the wounds in Wilkerson’s life. The historical segments have visually distinct appearances, and editor Spencer Averick cuts between them freely—in a manner that recalls how Cloud Atlas (2012) used multiple stories across time to draw out similarities—making visual associations even when Wilkerson’s often-present narration does not. When her line of reasoning begins to congeal, the editing becomes more fluid. Finally, when she presents her arguments on stage, the viewer sees the network of hate amid how Nazis treated concentration camp victims, how Africans were packed into slave ships bound for America, and how Dalits are forced to clean public toilets. But in each case, the visuals serve Wilkerson’s arguments more than her story. The sole exception is an expressive slow-motion dream, where Wilkerson, on a bed of fallen leaves, mourns several family members.

Many of the stories uncovered in Wilkerson’s research overshadow the power of her biographical portions. Take an account from a man who, in 1951, felt helpless while a fellow Little League player was ostracized from a public pool for being Black. Brief stories such as these resonate more than Wilkerson’s underdeveloped screen presence. Though powerfully performed by Ellis-Taylor, the character serves more as the viewer’s guide as she attempts to prove her hypothesis, despite occasional moments of tenderness. There’s a vital scene where a MAGA-hat-wearing plumber (Nick Offerman) tries to quickly dismiss Wilkerson, until she attempts to identify with him as a fellow human being, and their connection is no longer disrupted by race or some manufactured social order. Origin is full of pointed moments, but the whole feels fractured and imbalanced, emphasizing its intellectual foundation more than its emotional one. A documentary would have better served Wilkerson’s ideas, yet there’s much here to think about and discuss, even if her story remains an afterthought.

Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)

Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)  Candyman

Candyman  Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom