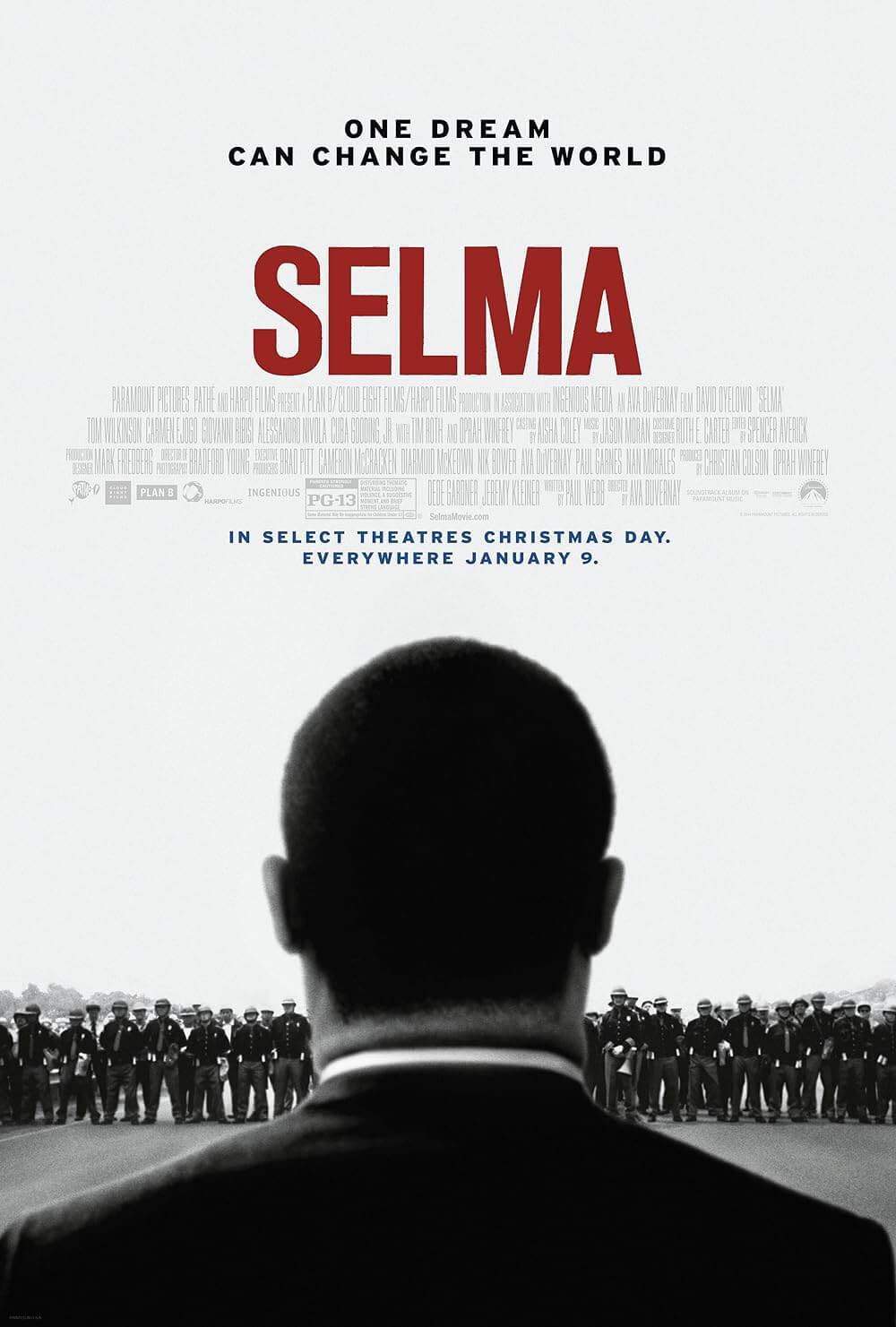

Selma

By Brian Eggert |

In the same way that Steven Spielberg focused on an episode of Abraham Lincoln’s push for civil rights in the film Lincoln as a small representation of a larger biographical canvas, filmmaker Ava DuVernay uses Selma as a microcosm to explore both Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement on film. Few films have been made about Dr. King, and almost none about the 1965 march from Selma, Alabama to the state capitol in Montgomery, but DuVernay’s expertly crafted picture tackles the material with just the right balance of historical and dramatic attention. Paul Webb’s balanced screenplay considers both the national and human sides of the story, never losing sight of his characters or the significance of the events before us. Not even the elegant performance by David Oyelowo as King distracts from the overall story, leaving Selma perhaps the best film about the civil rights movement since Spike Lee’s Malcolm X.

Just five short decades ago, desegregation may have been in place according to law, but it was not enforced in the Jim Crow South. President Lyndon B. Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) had passed the Civil Rights Act in 1964, but African Americans who wished to exercise their newly won right to vote, and who otherwise outnumbered white populations in the South, were met at voter registration booths by an opposing white power, reinforced by Alabama’s famously racist Governor George Wallace (Tim Roth). On this battleground, Dr. King and his party arrive and know unequivocally that Selma is just the hotbed they need to draw attention to their cause, in part due to the short-tempered, intolerant local Sheriff Jim Clark (Stan Houston). And it’s just the kind of exposure they need after their failed, yearlong desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia. To succeed, King needs not only media exposure but backing from the White House, and Webb’s script goes back-and-forth between King’s grassroots campaign and his lobbying with LBJ.

But King is also operating in one of the most tumultuous periods in history, with the Vietnam war raging, Malcolm X’s assassination approaching (Nigel Thatch appears onscreen as the figurehead, in an uncanny resemblance), and J. Edgar Hoover (Dylan Baker) at his most paranoid. The opening scenes demonstrate this sharply, cutting from King receiving a Nobel Peace Prize to the bombing of a Birmingham church where four girls died. Meanwhile, King also has a family to consider, including his wife, Coretta (Carmen Ejogo), who receives wiretaps of King’s extramarital affairs at their home. And even with the possibility of losing focus in the shuffle of such political and personal turmoil, Selma demonstrates how King could balance such chaos and remain, for the most part, composed. Of course, there are a couple of false-starts to the marches, one that involves a sweeping setpiece on Edmund Pettus Bridge where Selma police attack peaceful demonstrators, but it all ends with LBJ’s Voting Rights Act of 1965.

DuVernay may be an American director—and a former publicist-turned-indie filmmaker with two features to her name—but she’s tapped some fine British talent for her cast: Wilkinson, Roth, Ejogo, and reteaming with her Middle of Nowhere star, Oyelowo. Having played Forest Whitaker’s activist son in The Butler, Oyelowo is versed in civil rights drama, though he disappears into Dr. King’s presence, so weighted by the responsibility on his shoulders and death threats everywhere he goes, and delivers the speaker’s uniquely inflected orations with impressive accuracy. Still, it’s not just an impersonation Oyelowo gives; it’s a full-fledged embodiment, which will undoubtedly earn Oyelowo award consideration. Only Oprah Winfrey, who also produced, yet appears onscreen as a Selma woman denied voter registration, takes us out of the film. Beyond that, DuVernay’s treatment is never at risk of being outshined by its performances, central or otherwise.

Looming debates about the historical accuracy, or lack thereof, in Selma‘s depiction of an N-word dropping LBJ and his role in the Selma marches may sour the experience for some, or at least bring the White House scenes into question—particularly a scene where LBJ seemingly taps Hoover to “take care of” King. From a certain point of view, these scenes are shocking; then again, the entire debate against Selma suggests that a filmmaker representing a moment in history isn’t allowed any leeway to interpret the events from a dramatic perspective for the audience’s sake. Moreover, Webb and DuVernay could not use King’s exact speeches within the film due to rights issues, a problem not exactly within their control. At any rate, filmmakers have been altering history for dramatic purposes since Homer wrote about the Trojan War, and today the same debate arises each time a new historical film arrives in theaters. For a history lesson, open a history book; otherwise, let’s just accept that film is an artistic medium allowing for a certain degree of interpretation.

On a technical level, cinematographer Bradford Young and editor Spencer Averick deliver a lightly styled, straightforward presentation that remains consistent from start to finish. If there’s a major quibble to be had, it’s the somewhat distracting, certainly paranoia-driving device where type-written FBI reports appear onscreen and detail Dr. King’s movements in Selma, fuelling the fear (and later arguments about historicity) that the government was against King. That aside, DuVernay has made a stirring, intelligent film about the civil rights movement, a subject that, surprisingly, so few motion pictures get right. It presents a single situation on an emotional and intellectual level, appealing to a vast range of its audience, which is something rare for this type of cinema. Most importantly, the film makes us reflect on a time not too long ago when things were very different, and also forces us to consider how far we still have yet to go.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review