Candyman

By Brian Eggert |

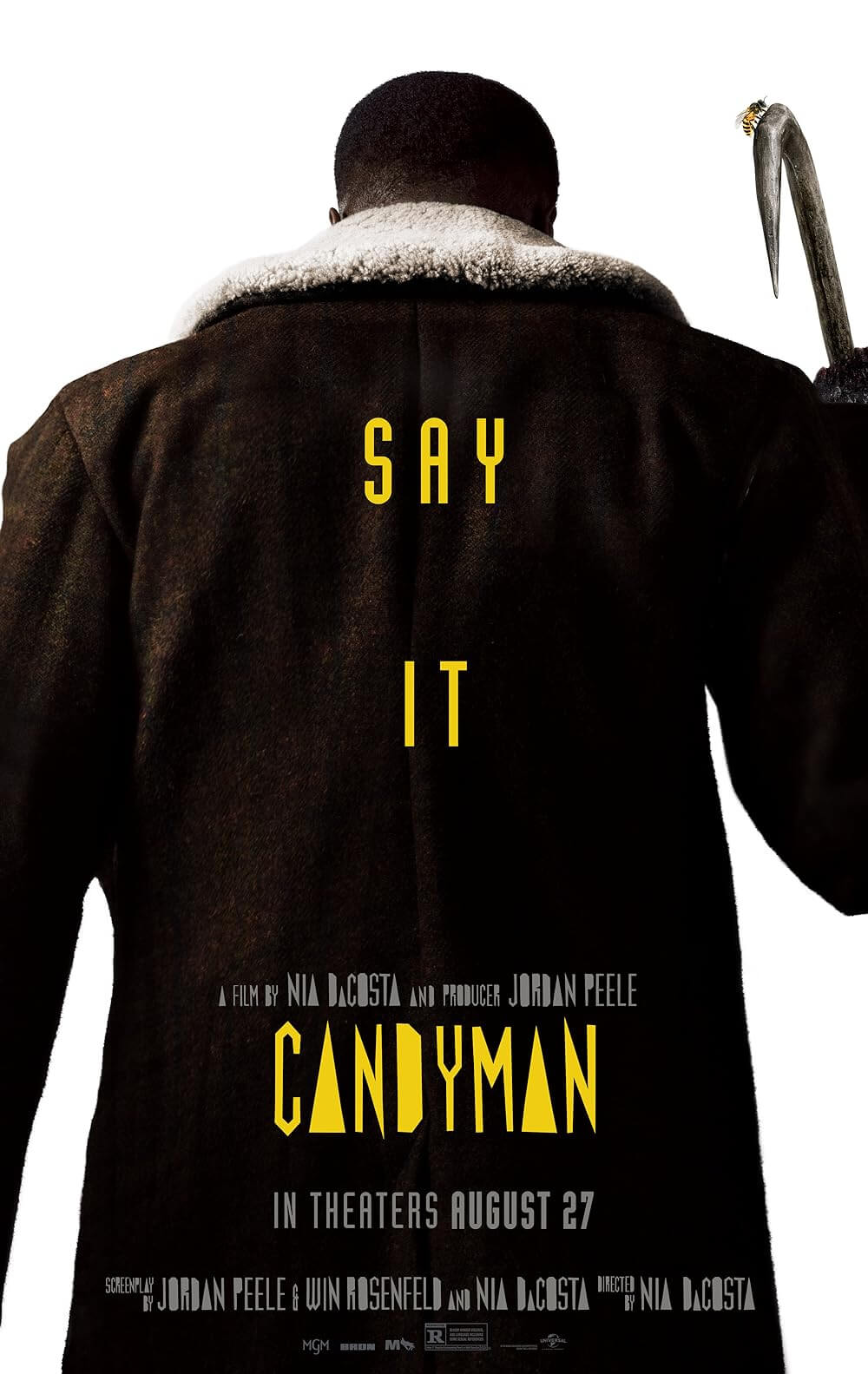

In Candyman, the collective memory of the Black community manifests into a monstrous figure. Dubbed a “spiritual sequel” to the 1992 original, the new film both reconsiders the earlier mythology—continued in two sequels, Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh (1995) and Candyman: Day of the Dead (1999)—and enhances its purpose, which has been informed by the last thirty years of cultural growth, digressions, and unchanging truths. Director Nia DaCosta refashions the narrative around a Black artist whose work taps into a shared past and reveals, through his artwork and a string of ghastly murders, the reality behind the ghostly force that consumes him—not as some distant mythology but an enduring symbol of how racial violence still haunts America’s headlines. Armed with a hook hand and a shroud of bees that harken back to the original figure, Candyman kills, but it’s not without reason in the new film; he shares the pain of racial violence experienced by countless before and after him. DaCosta builds upon the thoughtful original to investigate the politics of race, gentrification, and history in a manner better suited to the metaphoric potential of horror, resulting in a far more decisive, clarified, and emotionally involving tale.

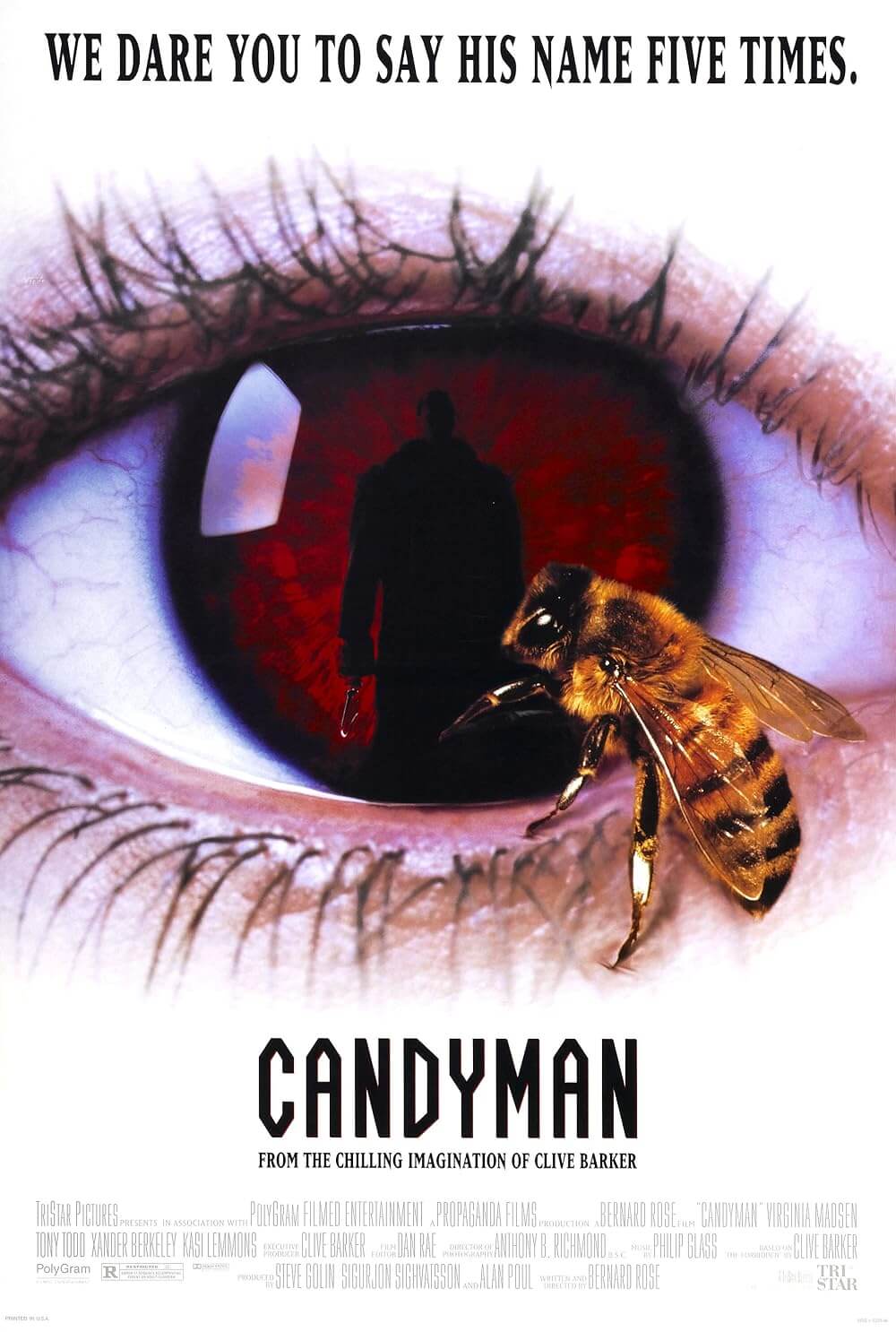

In the original version by English filmmaker Bernard Rose, based on a story by Clive Barker, Tony Todd played Daniel Robitaille, the educated son of a slave who paints the portrait of a white woman. Robitaille and the woman fall in love, she becomes pregnant, and her bigoted father retaliates by setting an angry mob loose on Robitaille. The throng chops off Robitaille’s hand and puts a hook in its place; then, they slather him in honeycomb, leaving him to die from countless bee stings. His myth lives on by saying his name five times in the mirror, summoning a bee-covered figure who slays his victims with a hook to remind people of the violence he suffered. But Robitaille isn’t the focus of DaCosta’s film. The new Candyman is Sherman Fields, a hook-handed man who gives candy to children in the housing project Cabrini-Green in 1977. When locals suspect him of putting razor blades in the candy, the police hunt him down and murder him. Only later do they realize they got the wrong man. A young boy named Burke witnesses, and mistakenly perpetuates, the tragedy of Fields’ death. Years later, Burke will conjure Candyman from the past. But history is full of prejudice-based crimes, and that, as it turns out, is the point.

Set in 2019, the new Candyman follows artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), who has just moved in with his art-dealer girlfriend Brianna (Teyonah Parris) in a posh apartment that stands on the gentrified land where Cabrini-Green used to be. Blocked, Anthony searches for his latest subject to display at the gallery where Brianna works when he hears about the Candyman myth from her brother. Anthony resolves to learn more and, exploring the neighborhood, he finds the adult Burke (Colman Domingo), now a laundromat owner gleefully spinning yarns about Candyman. Anthony grows fascinated and even obsessed, especially after learning that there’s some truth behind the Candyman myth. When his eventual installation, entitled “Say My Name,” appears at the gallery, he introduces unimpressed critics and patrons to the myth. His piece is a mirror that, if the viewer looks beyond the surface, they see a history of violence, oppression, and gentrification; if not, they see only themselves reflected. The film’s setting among artists and galleries gives way to the notion of Black trauma getting consumed as a commodity by white audiences and critics, putting the emotional reality at a safe distance. Even so, when spectators follow Anthony’s artistic prompt and say “Candyman” five times, the new Sherman Fields version of Candyman, the version Anthony learned about from Burke, slays them in gruesome fashion.

Set in 2019, the new Candyman follows artist Anthony McCoy (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), who has just moved in with his art-dealer girlfriend Brianna (Teyonah Parris) in a posh apartment that stands on the gentrified land where Cabrini-Green used to be. Blocked, Anthony searches for his latest subject to display at the gallery where Brianna works when he hears about the Candyman myth from her brother. Anthony resolves to learn more and, exploring the neighborhood, he finds the adult Burke (Colman Domingo), now a laundromat owner gleefully spinning yarns about Candyman. Anthony grows fascinated and even obsessed, especially after learning that there’s some truth behind the Candyman myth. When his eventual installation, entitled “Say My Name,” appears at the gallery, he introduces unimpressed critics and patrons to the myth. His piece is a mirror that, if the viewer looks beyond the surface, they see a history of violence, oppression, and gentrification; if not, they see only themselves reflected. The film’s setting among artists and galleries gives way to the notion of Black trauma getting consumed as a commodity by white audiences and critics, putting the emotional reality at a safe distance. Even so, when spectators follow Anthony’s artistic prompt and say “Candyman” five times, the new Sherman Fields version of Candyman, the version Anthony learned about from Burke, slays them in gruesome fashion.

In other words, Anthony’s art denies passive viewership. Those who engage will either open the mirror to see his painted depictions of violence or, when they summon Candyman, will experience first-hand the full physical torture of those like Robitaille or Sherman who were robbed of their lives by horrific violence. Accordingly, DaCosta creates jarring onscreen deaths that never play like the fun, escapist kills of your average slasher fare. Rather, they’re deeply unsettling and marked by a sharp blend of practical effects and CGI. Some of the violence is all the more effective because DaCosta frames the killings from a distance. Possessed by the inevitability of Candyman, Anthony dares a pretentious white critic to say “Candyman” five times in her mirror, as if he knows what will happen. When she’s slain, we see the action from outside her apartment window, and our removal from the situation makes us feel helpless, heightening the terror. The same is true of a sequence involving several teenage girls who resolve to make light of the Candyman myth; their fate is represented off-screen or through mirrored surfaces.

DaCosta’s Candyman never feels repetitive; much like the film’s myth, it adopts iconic imagery and adds a new layer. Take her use of mirrors as both reflectors of violence and thresholds between the real and mythological, behind which both the titular specter and his accompanying bees reside—the sound of them tapping on mirrors from within makes for a creepy aural effect. Forget the usual slasher scares or bloodshed for the fun of it. Even Brianna reveals herself to be a refreshingly smart “final girl” who considers going into a dark basement but declares, “Nope.” When she’s faced with a pursuer later in the film, she stabs the man over and over again until he’s good and dead, leaving no chance that he’ll get up again. Of course, given DaCosta’s thoughtfully considered work on the familiar-yet-original rural noir, Little Woods (2019), it’s no surprise that Candyman looks visually composed as well. Cinematographer John Guleserian captures the art scene, flashbacks, and grimier sequences of violence with memorable clarity, and the images never resort to familiar or allusive visual reference points for inspiration.

To be sure, DaCosta’s treatment reframes the original from the outset. The original opened with a God’s-eye-view of Chicago, establishing an almost supernatural distance from above. The new film’s title sequence looks up and back, as though the perspective came from someone on the ground looking up at skyscrapers shrouded by fog. The effect is claustrophobic, hopeless, and desperate, underscoring the film’s sense of feeling trapped by successions of racial discrimination. It’s as though the viewer sees the film’s world as a dark reflection—a distortion of what the world should be. Similarly, when DaCosta’s characters reflect on the past, she portrays the events with shadow puppets. A prologue set in Cabrini-Green in 1977 shows Burke playing with puppets and mythologizing the reality of police violence. Burke’s closeness to the Candyman myth and tendency to use shadow puppets to extend that myth become essential later in the story. During the end credits sequence, the angular black puppets return to retell the Candyman stories told in 1992 and 2019, and those in-between. After all, racial violence did not begin with Daniel Robitaille and end with Sherman Fields.

To be sure, DaCosta’s treatment reframes the original from the outset. The original opened with a God’s-eye-view of Chicago, establishing an almost supernatural distance from above. The new film’s title sequence looks up and back, as though the perspective came from someone on the ground looking up at skyscrapers shrouded by fog. The effect is claustrophobic, hopeless, and desperate, underscoring the film’s sense of feeling trapped by successions of racial discrimination. It’s as though the viewer sees the film’s world as a dark reflection—a distortion of what the world should be. Similarly, when DaCosta’s characters reflect on the past, she portrays the events with shadow puppets. A prologue set in Cabrini-Green in 1977 shows Burke playing with puppets and mythologizing the reality of police violence. Burke’s closeness to the Candyman myth and tendency to use shadow puppets to extend that myth become essential later in the story. During the end credits sequence, the angular black puppets return to retell the Candyman stories told in 1992 and 2019, and those in-between. After all, racial violence did not begin with Daniel Robitaille and end with Sherman Fields.

Detractors of DaCosta’s film have pointed out that the screenplay, co-written by Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld, articulates its commentaries and social consciousness almost too well. If Candyman engages in an open discussion about its themes, it’s because the original, too, undertook an intellectualized study of these issues. The 1992 film featured a privileged grad student played by Virginia Madsen researching the nature of mythology and folklore in the Black community around Cabrini-Green, until her white liberal guilt leads to her being consumed into the myth. DaCosta’s film reframes the mythology through a Black lens in a political culture that more actively and openly discusses these issues. Moreover, her characters feel shaped by the central myth, whether from revelations or patterns in their lives. Beyond intellectualized matters of race, both Anthony and Brianna have deeply personal reasons to feel invested in what’s happening—he was kidnapped by the Robitaille-Candyman as an infant, as seen in the 1992 film; she feels inextricably linked to doomed artists. Still, it’s only fitting that the screenplay should address loftier themes, since its characters around the art community steep themselves in debates about representation. Both versions of Candyman can’t help but feel slathered in readable contexts because, quite simply, that’s what they’re about.

DaCosta’s film also surpasses the original by enriching and refining some of Rose’s unclear plot points and motivations. 1992’s Candyman could be faulted for relying too heavily on the tropes of 1990s-brand slashers, featuring Freddy Krueger, Jason Voorhees, or Michael Myers. Much of its midsection, and its two sequels, feel dependent on creating memorable kills for an audience accustomed to formulaic and mindless onscreen death. What’s more, Rose’s Candyman kills somewhat indiscriminately, whereas DaCosta’s version seems to have an agenda in selecting his victims—or perhaps more clearly defined motivations. There’s also the original’s last few minutes, which find Madsen’s character, now haunting her former lover by using Candyman’s mirror routine, in a conclusion that arguably diminishes the theme about the power of Black pain and myth. And while the new Candyman features several memorable and well-staged deaths, it’s not what you would consider a slasher film. Instead, Burke repositions the Candyman myth within a larger cycle of monsters created by racial violence throughout history. “Candyman ain’t a ‘he,’” Burke tells Brianna. “Candyman is the whole damn hive.”

In another scene-stealing performance by Domingo, Burke is a character so determined to remind his community about America’s history of white aggression perpetrated against Black people that he actively builds upon the myth. Early in the film, a bee stings Anthony’s hand not far from Burke’s laundromat. The sting mark grows increasingly necrotic throughout the film, first spreading across his hand, then up to his arm. By the time the infection reaches Anthony’s face, it looks like a honeycomb, filled with pocks bound to give trypophobics a nervous breakdown. It’s a downright Cronenbergian symbol for how Anthony loses himself to the historical reality of racial violence with the help of Burke, who recasts Anthony by completing his transformation with a saw and hook. With this change, the climactic scenes adjust perspective sharply from Anthony to Brianna, who watches Anthony become the new Candyman with abject horror, even while she’s cognizant of its necessity. Some have called these narrative and symbolic maneuvers rushed or muddled; on the contrary, they feel effectively disorienting in their ability to compel Anthony and Brianna to confront their collective past and present.

In another scene-stealing performance by Domingo, Burke is a character so determined to remind his community about America’s history of white aggression perpetrated against Black people that he actively builds upon the myth. Early in the film, a bee stings Anthony’s hand not far from Burke’s laundromat. The sting mark grows increasingly necrotic throughout the film, first spreading across his hand, then up to his arm. By the time the infection reaches Anthony’s face, it looks like a honeycomb, filled with pocks bound to give trypophobics a nervous breakdown. It’s a downright Cronenbergian symbol for how Anthony loses himself to the historical reality of racial violence with the help of Burke, who recasts Anthony by completing his transformation with a saw and hook. With this change, the climactic scenes adjust perspective sharply from Anthony to Brianna, who watches Anthony become the new Candyman with abject horror, even while she’s cognizant of its necessity. Some have called these narrative and symbolic maneuvers rushed or muddled; on the contrary, they feel effectively disorienting in their ability to compel Anthony and Brianna to confront their collective past and present.

Candyman is a rarity—an accomplished horror sequel that manages some intelligence and sociopolitical insight, while at the same time negotiating the muddy waters of an established franchise, operating at a breezy clip, and even surpassing its predecessors. Candyman could have been a cash-grab that exploited its intellectual property for some cheap thrills. But it acknowledges the downfalls of its predecessor and corrects them, partly by exploring Candyman’s relationship with the Black community, and partly by reconsidering the story’s subjectivity in vital ways—Candyman’s origin and whom he decides to kill prove telling. Alongside DaCosta as Candyman’s co-writer and producer, Peele helps establish a cohesive symbolic purpose to the film’s horror, reflecting his directorial work on Get Out (2017) and Us (2019). Hinted by Robert A. A. Lowe’s winding, cyclical music that knows better than to abandon Philip Glass’ hypnotic theme from the original, the film examines mythology as a method of telling the same story again and again—because the reality of racial violence is that it happens daily. Candyman becomes an icon of what’s happened and what continues to occur. “Pain like that lasts forever,” says Burke. “That’s Candyman.”

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review