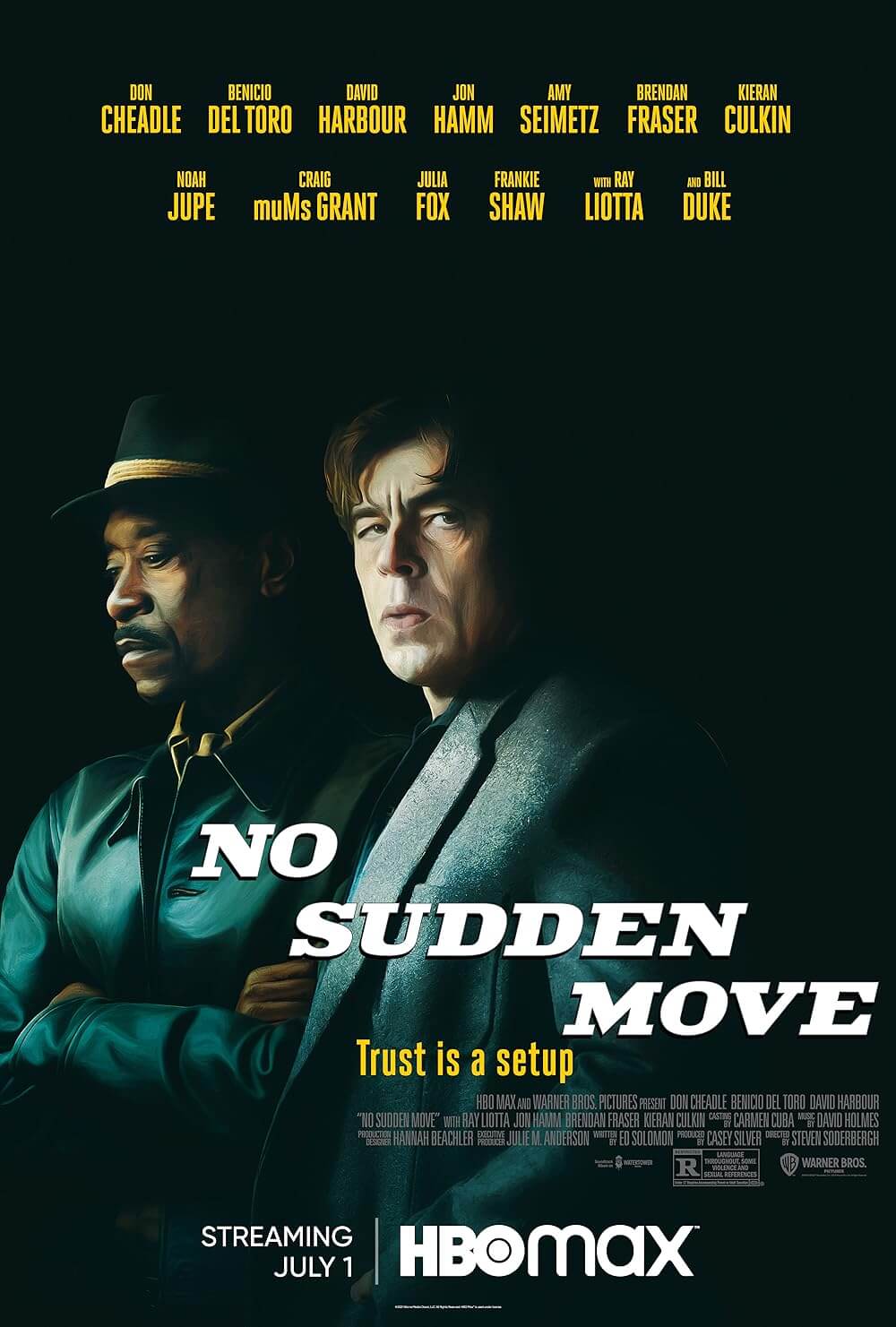

No Sudden Move

By Brian Eggert |

Just out of prison, Curt Goynes takes a job babysitting a family in suburban Detroit. It’s not that kind of babysitting: He and another masked man hold mom and her two children at gunpoint, while a third takes dad to General Motors where he works as an accountant. While dad tries to acquire a document locked in his boss’ safe, Curt and the other masked man tell mom and the kids to behave like it was a “normal Monday.” No Sudden Move takes place in 1957, and so normality looks Rockwellian. Mom puts on her apron to prepare cereal. Dad wears horn-rimmed glasses and a tie to work. But from the outset, director Steven Soderbergh and screenwriter Ed Solomon, who crafted the interactive series Mosaic together, question the stability of every institution held sacred by 1950s America. And that extends from the nuclear family to interrelated forces of capitalism, the automotive industry, and organized crime. The order in this film’s universe doesn’t reveal itself at first, and everyone’s expectations of what happens next will be upended. The petty crime isn’t so petty, unbeknownst to its perpetrators, and there’s more behind everyone than their roles suggest.

Soderbergh returns with another Motor City caper starring Don Cheadle, his second after Out of Sight in 1998. It’s comfort food for a director whose mercurial career has always been unpredictable, the last few years more than ever. His recent work includes a paranoid thriller (Unsane, 2018) and a basketball drama (High Flying Bird, 2019), both experiments in shooting on smartphones. He made a goofball takedown of tax shelters and shell corporations (The Laundromat, 2019), arguably his least successful film to date, and a chatty Meryl Streep dramedy set on a cruise ship (Let Them All Talk, 2020). Working almost exclusively with streaming services like Netflix and HBOMax, Soderbergh recently signed a three-year deal to produce films and shows for the latter company. And his latest reflects his penchant for crime stories ranging from Elmore Leonard adaptations to various slick heist ensembles. For fans of his work, watching something like No Sudden Move feels familiar and welcoming.

Whether it’s trying to keep up with Daniel Ocean or the Logan brothers, the joy of watching a Soderbergh caper is how his characters, always played by top-notch performers, respond under pressure. Cheadle stars as Curt, a scrappy survivor known on the street for lifting a codebook that belonged to a local crime boss, Watkins (Bill Duke), which has made him a marked man. Benicio del Toro plays Ronald, an accomplice who drinks like a fish and has a low view of Black people. Both took the job from a testy intermediary, Mr. Jones (Brendan Fraser), whose employer remains a secret, at first anyway. As long as it’s not Frank (Ray Liotta)—neither of them wants to work with him. They’re also teamed with a hotheaded third man, Charley (Kieran Culkin), whose behavior threatens the Wertz family, Matt (David Harbour) and Mary (Amy Seimetz). Curt and Ronald don’t want any violence, but they’ve been sold on a job they know nothing about.

Here’s a film that has the logline of a juicy yarn involving gangsters and hold-ups, but it has the texture of something more intricate. Soderbergh’s portrait of 1950s America feels like Richard Yates’ take in Revolutionary Road, where people living seemingly idyllic lives are revealed to be miserable. Matt is sleeping with his secretary (Frankie Shaw) and plans to leave the disenchanted Mary, who’s tired of keeping up appearances and might have something going with her neighbor (Katherine Banks). When asked, the Wertzes explain, “we’re fine,” though it’s clear they’re miserable together. Seimetz doesn’t have much to do besides worry and wait in her character, but she also plays the film’s most complex role. She’s smart enough to observe to her son (Noah Jupe), “They don’t want to hurt us. That’s why they’re wearing masks.” But she’s also jaded and sarcastic when detectives ask why she thinks her family was targeted. Her response is that the perps don’t “like happiness”—a crass remark considering there’s a dead body in her kitchen and Matt slept on the couch the night before. Even the criminals have added layers, such as Ronald’s affair with Vanessa (Julia Fox), a woman plotting her own freedom two steps ahead of (almost) everyone else. Nearly every man has a woman on the side, and nearly every woman feels trapped in their domestic roles with men.

No Sudden Move is full of double-crosses that gradually reveal a much larger scheme than petty thugs like Curt and Ronald have managed before. With each new wrinkle in the story, the bounty on their heads goes up, but then, so does their prospective payday. Curt originally agrees to accept $5K for three hours of work; then, as opportunities present themselves, his potential take elevates to $50K, followed by $125K, and finally over $400K. Each new possibility means another well-laid plan that inevitably goes wrong, another violent encounter, and yet another figure pulling strings behind the curtain. It’s not enough that Frank is involved. But who hired Frank, and who paid the guy who hired Frank? And then there’s Detective Joe Finney (John Hamm), fast on their trail. It’s an unpredictable series of events, but it’s also handled with a wry sense of humor. The playfulness is emphasized by David Holmes’ jazzy score, recalling Henry Mancini’s upbeat music in Charade (1963).

Serving as cinematographer and editor under his usual pseudonyms, Soderbergh replicates the look of a classy ‘50s or ‘60s thriller. He shoots in the style of the period, using indulgently wide-angle lenses, with which he seems to delight in creating barrel distortions on either side of the screen. The colors appear muddy and muted, the setting overcast or rainswept—albeit in a manner that enhances the detailed production design and costumes. Aside from a few self-conscious camera movements that shift into a Dutch tilt for effect, the aesthetic is immersive, allowing the film’s themes to grow. Before long, Curt and Ronald find themselves confronted with the realities of gentrification; auto pollution; cops owned by corporations; and the combined forces of Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler. If a late speech by Matt Damon threatens to put too fine a point on these factors, it’s also a very good speech—shattering in its points about class, “or caste,” as he adds, and the rich’s ability to acquire more wealth. “I work; it grows. I sleep; it grows.”

No Sudden Move could be taken for a trifle, in the same way that someone could watch Steve McQueen’s Widows (2019) and see nothing more than a well-crafted heist film, dismissing its remarks about race and power. Rather, this is Soderbergh’s best film in years, combining his penchant for crime, humor, and critique. It reminds us how his greatest works endeavor to be entertaining takedowns of corrupt systems, populated by layered characters and novelistic detail. Whether he’s poking holes in the war on drugs (Traffic, 2000), psychopharmacology (Side Effects, 2013), our pandemic preparedness (Contagion, 2011), behavior hospitals that pad insurance claims (Unsane), or corn price-fixing (The Informant!, 2009), Soderbergh specializes in targeting broken institutions. No Sudden Move looks at how an entire city—nay, the entire country—was shaped by rich white men in the automotive industry who sought to grow their obscene fortunes, and how everyone, from the American family to small-time (and big-time) hoods, remains subject to those power dynamics. In that realm, the film’s low-level criminals play like tragic heroes.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review