The Definitives

Zodiac

Essay by Brian Eggert |

From the late 1960s to early 1970s and beyond, Zodiac Killer mania rattled the San Francisco Bay Area of northern California. With several confirmed attacks and numerous others attributed to his name, the self-titled Zodiac claimed to have 37 victims; however, just three men and two women died by either gunshot or stabbing, while another two were seriously injured but escaped. The murders themselves were frightening enough, but then on August 1, 1969, the Zodiac began to write letters to newspapers. Their coverage launched the fervor to a new level. Not since Jack the Ripper had such a high-profile killer written the press and teased authorities with hints to his identity. The San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Examiner, and Vallejo Times-Herald each received letters with specific information only the killer could know, cryptograms that when deciphered revealed a feverish rant, and most signed with either the zodiac symbol (crosshairs) or his name (“Dear Editor: This is the Zodiac speaking…”). Whether their author mocked the police’s inability to catch him, claimed to be collecting slaves for the afterlife, or promised to shoot children on a school bus, Zodiac’s published correspondence resulted in frantic reactions from authorities and the public. The coverage even led to a response in popular culture, when Hollywood used the Zodiac for inspiration in Dirty Harry (1971), and therein delivered a catharsis that would never come. As the letters stopped after 1974 and the killings four years earlier, the panic died down, albeit without resolution. The Zodiac investigation remained open without a single arrest or even conclusive suspect, and remains open still, a mystery that continues to consume investigators yet will remain forever unsolved.

An all-consuming need to disentangle an unsolvable mystery impels David Fincher’s masterful procedural, Zodiac. James Vanderbilt based his true-crime script on Robert Graysmith’s nonfiction investigations of the case, Zodiac: The Full Story of the Infamous Unsolved Zodiac Murders in California (1986) and Zodiac Unmasked: The Identity of America’s Most Elusive Serial Killer (2002). Vanderbilt’s screen story does not offer artificial solutions, nor does it provide answers to questions the 2007 film could not possibly answer. Over nearly three hours and covering over three decades from 1969 to 1991, Fincher wraps viewers in the same insatiable, unsatisfied obsession that drives its four central characters—among them the unlikely Graysmith, a shy cartoonist and Eagle Scout—to keep searching for answers long after the Zodiac has disappeared from the spotlight. Fincher ensures our investment in the murders by reenacting them in virtuoso scenes of fearsome tension informed by a shocking degree of factual realism. But then, the film also saturates our minds with fastidious details: the names of victims, dates, and locations of crimes, bits of evidence, a list of suspects, telling connections between clues, breakthroughs and obstructions in the case, and even a red herring or two. He reverberates his characters’ obsessions onto the audience, instilling how the investigators were overcome by the Zodiac case—how it represented a far-reaching importance over all other aspects of their lives and a sense of personal significance to resolve, while also alienating them from their friends and family until they reached the brink. Through it all, they never achieve unequivocal proof and the case is never categorically closed.

Dark thrillers and serial killers have shaped Fincher’s career. Among his most popular films is the pivotal Se7en, the genre-redefining yarn from 1995, about a serial killer using the mythic seven deadly sins as inspiration for his grisly crimes. Fincher also adapted Swedish author Stieg Larsson’s popular book The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) into an intricate serial killer mystery. Elsewhere, Fincher’s work achieved an enthusiastic cult status with his black-and-bloody satire of modern masculinity, Fight Club (1999). He delivered suspenseful, twisting genre pieces with The Game (1997) and Panic Room (2002). And he encapsulated our modern way of communicating, or inability to, with the Mark Zuckerberg-Facebook showcase, The Social Network (2010). With each new entry in his career, a few qualities about his work remain consistent. The most obvious of them are his distinct visual proclivities: his use of low angle pans; his frequent unbroken tracking shots; his use of darkness, especially when combined with digital cameras that capture more light, or employing a re-silvering process to celluloid to allow more grain and therefore more light onto the film. The smoky, atmospheric quality of his films echo their content. In terms of narrative, Fincher has said that, more than mere entertainment value, “I’m always interested in movies that scar.” In almost every case, films bearing Fincher’s name have left an unrecoverable mark on their audience. None more so than Zodiac. Indeed, Fincher had told scorer David Shire, “I don’t want to make another serial killer movie. I want to make the last serial killer movie.”

The project had been a passion of Vanderbilt’s since he read Graysmith’s first book in high school. The screenwriter arranged with Phoenix Pictures to write a spec script based on Graysmith’s writings, while they secured the rights. Fincher was their first choice to direct, based on his previous experience. But Fincher himself had a close relationship with the killer already, having grown up in the San Francisco Bay Area around the time the Zodiac was active. “If you grew up there, at that time, you had this childhood fear that you kind of insinuated yourself into,” he said. “What if it was our bus? What if he showed up in our neighborhood? You create even more drama about it when you’re a kid because that’s what kids do.” Though no victims were killed in Fincher’s hometown of Marin, he said, “When you’re in grade school, children don’t think about that. They think, ‘He’s going to show up at our school.’” Because of his experience with the hysteria around the mythologized killer, Fincher set out to dispel the myth. Along with Vanderbilt, of whom Fincher requested a script re-write to include more factual information, the director spent more than a year researching details of the case to prepare. He read thousands of pages of evidence; he interviewed survivors, loved ones of victims, and policemen involved in the investigation; he talked to the prime suspect’s family; he reviewed the site of every crime. His obsession would eventually mirror that of his film’s characters, who succumb to their own terrible need to know.

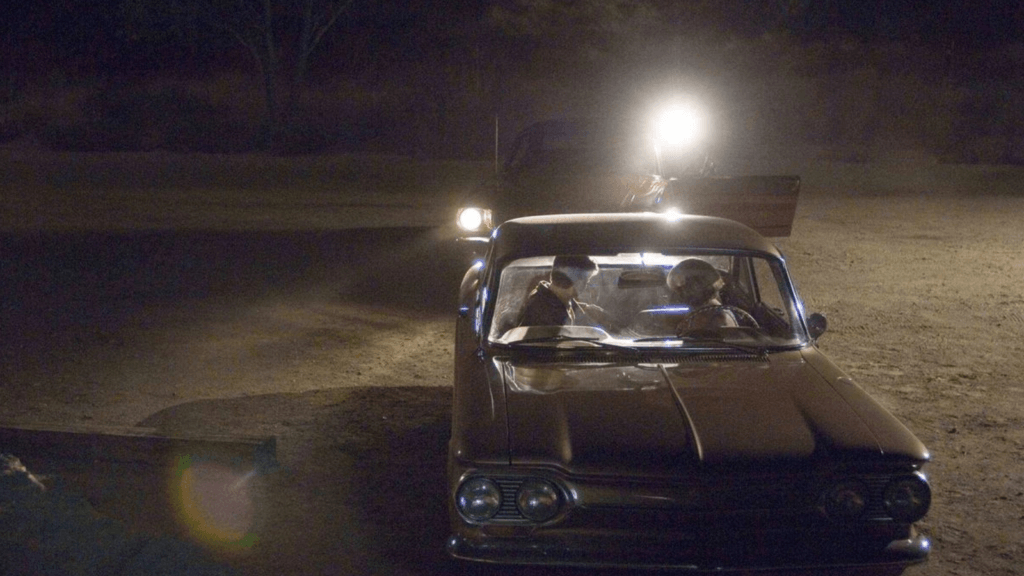

The film opens in Vallejo, California, 1969, with a confronting opposition of Fourth of July fireworks and festivities, all set against Three Dog Night’s aching “Easy To Be Hard” on the soundtrack. As Chuck Negron’s breezy voice sings, “How can people be so heartless, how can people be so cruel?” Fincher introduces us to a calm, inviting suburban neighborhood, carefree, children scampering about. We pan along, looking outside the front passenger’s side window of Darlene Ferrin’s (Ciara Hughes) car. She stops to pick up her date, Michael Mageau (Lee Norris), and they head to a burger joint. There, Darlene suddenly looks nervous and suggests they pull into a local Lover’s Lane. Before long, a second car joins them, and she seems to recognize it. Immediately the mood changes. Donovan’s rather haunting “Hurdy Gurdy Man” occupies our ears; the lyrics about tranquility being interrupted by the Hurdy Gurdy Man’s song give us an uneasy feeling. Just as quickly as the other car leaves and delivers a sigh of relief, it returns and parks behind them with its headlights filling their mirrors, so they can see nothing specific about the vehicle. The lovers assume it’s the police and get out their wallets. A dark shadow emerges with a flashlight and approaches Mageau’s side, directing the light into his eyes. And then five shots ring out, and Ferrin and Mageau convulse with bullets. The figure begins to leave, then comes back to put another two bullets into each of them. Ferrin dies. Mageau, somehow, survives. Later that evening, an anonymous caller to the police confesses to the attack, as well as a similar attack on a young couple from December of 1968. Though this was not the first Zodiac killing, Fincher shows us that nothing is sacred for the Zodiac: not a national holiday; not Small Town, America; not the innocence of youth. He can get anyone at any time.

Nearly a month after this shooting, the Zodiac’s first letters arrive at the San Francisco Chronicle and other papers, and self-destructive journalist Paul Avery, brilliantly played by Robert Downey, Jr., begins his famous coverage of the story. Accustomed to covering the beat, Avery sees through Zodiac’s scheme and manipulation of the media, later remarking, “More people die on the East Bay commute in three months than that idiot ever killed.” Avery’s scenes in the newspaper room recall those in Alan J. Pakula’s political thriller All the President’s Men (1976), where editors question the consequences of publishing Zodiac stories and letters, especially given his clear need for attention. After all, they could be encouraging him, but perhaps that’s what he wants. It’s not until San Francisco taxicab driver Paul Stine is murdered that the SFPD Inspectors David Toschi (Mark Ruffalo) and William Armstrong (Anthony Edwards) are brought onto the case. Before this, Zodiac’s killings seemed reduced to “Vallejo farm kids.” Toschi and Armstrong must now manage the Bay Area’s growing panic. They’re pulled along with Zodiac’s careful bid for media attention, such as his televised interview with quasi-celebrity Attorney Melvin Belli (Brian Cox) on a talk show. All the while, the growing list of 2,300 suspects is gradually interviewed by detectives, many of them cleared by a handwriting expert, Sherwood Morrill (Phillip Baker Hall). After years of investigating, Armstrong, unwilling to play Zodiac’s game and frustrated by their lack of progress, resolves to move on from homicide. The media and internal affairs eventually turn on Toschi, accusing him of propelling and tampering with the case. And Avery, who sees Zodiac as “good for business,” descends on a downward spiral of substance abuse and hits bottom once the Zodiac’s letters stop arriving at his paper.

On the periphery the entire time, maintaining his interest from a distance, Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal) remains a quiet, polite, and excitable political cartoonist enthused about the case, especially the cryptograph the killer includes with his letter. The puzzle combines astrological symbols, Morse code, characters from the alphabet, Greek language, weather symbols, and Navy semaphore in a cipher not even codebreakers for the CIA, the FBI, the National Security Agency could solve. After the Salinas-based couple, the Hardens, decode the Zodiac’s 312-symbol message, Graysmith realizes it’s a reference to the 1932 film, The Most Dangerous Game, about a hunter of men. Graysmith begins his own investigation, which continues on long after others have either given up or been forced out, when the killer’s activity goes cold in 1974. Graysmith’s obsession with the case costs him his wife (Chloë Sevigny), his children, and eventually his job. But his absorption—almost fixation—on the case allows him to cut through the jurisdictional restrictions that prevented four police departments in various cities from communicating effectively, painting himself an entire picture that, when bringing Toschi into his investigation later, leads them to a prime suspect, never charged: Arthur Leigh Allen (John Carroll Lynch), whose guilt can never be unequivocally proven. Much of the evidence against Allen is circumstantial, but Graysmith’s spine-tingling encounter with Allen at a Vallejo Ace Hardware store, where Allen was working, seems to confirm all of Graysmith’s suspicions.

Filming of Zodiac began in September of 2005 and wrapped the following February, but the film would not be released for more than a year due to extensive post-production requirements. For the first time, Fincher used digital cameras, shooting in dark lighting conditions with a Thomson Viper Filmstream Camera that allows for a crisp image (although, some extreme slow-motion scenes still required the use of celluloid). Cinematographer Harris Savides had worked with Fincher on Se7en and The Game, but never used digital HD photography on one of Fincher’s films; he was told to expressly avoid the look of those films for Zodiac. Quite the opposite of Fincher’s other work, there’s a visual restraint throughout the picture. The director recreates the grainy, washed-out colors of 1970s cinema by underexposing or color-timing his shots, creating moodier interiors and clearer nighttime scenes. Of course, many night images and pressroom colors match those of All the President’s Men, while other evidence of Fincher’s usual technical mastery is more recessive. Take how Zodiac recreates the landscape of the period. Buildings and skylines that no longer exist due to land development and gentrification in San Francisco in subsequent years are recreated using flawlessly integrated CGI—over 200 visual effects shots in all, so seamlessly integrated the viewer never notices them. We simply accept the environment of the film as the Bay Area of the 1960s and ’70s, which was reconstructed using photographs from the era. Even an artificially created, increased frame-rate sequence showing the development of San Francisco looks as though Fincher went back in time and used a time-lapse camera over the course of several years to render the shot.

Both visually and thematically, Fincher’s films are bathed in darkness. With an HD camera’s ability to better capture ambient light and the ambiguities therein, the effect on Zodiac suggests the film will shine a light on the central mystery, bringing the mystery out into the open; and when it doesn’t, it furthers our craving for a definitive answer. The procedural approach taken by Fincher follows the investigation, but only from Graysmith’s perspective. Never is there a scene from the killer’s perspective, looking in on the murder, because the Zodiac remains a mystery, shrouded by shadows. By keeping the audience at a distance and spectating as viewer-investigators, Fincher saturates us in details and the horrifying reality of what happened, avoiding subjective angles whenever the Zodiac is involved. The film replicates every minute detail, from the clothing of the victims to the representations of the Zodiac according to witness descriptions. Rather than casting Lynch as Zodiac for the four murder sequences shot, Fincher casts multiple actors in the role; in fact, none of them are played by Lynch, designing their look based on his sightings. Part of the film’s brilliance as true-crime is that, over the course of its nearly three-hour runtime (157 minutes theatrically, 162 minutes in the Director’s Cut), the film resists dropping clues for the audience. Had this been a lesser piece, the filmmakers would have made the audience smarter than the investigators, allowing the viewer to discover who the killer is just a moment or two before the protagonist. But Zodiac is atypical in that its purpose is not to create suspense, but through the gradual discovery of clues, to reproduce the obsession that lingers for Graysmith, Toschi, and many others involved in the original investigations, to this day.

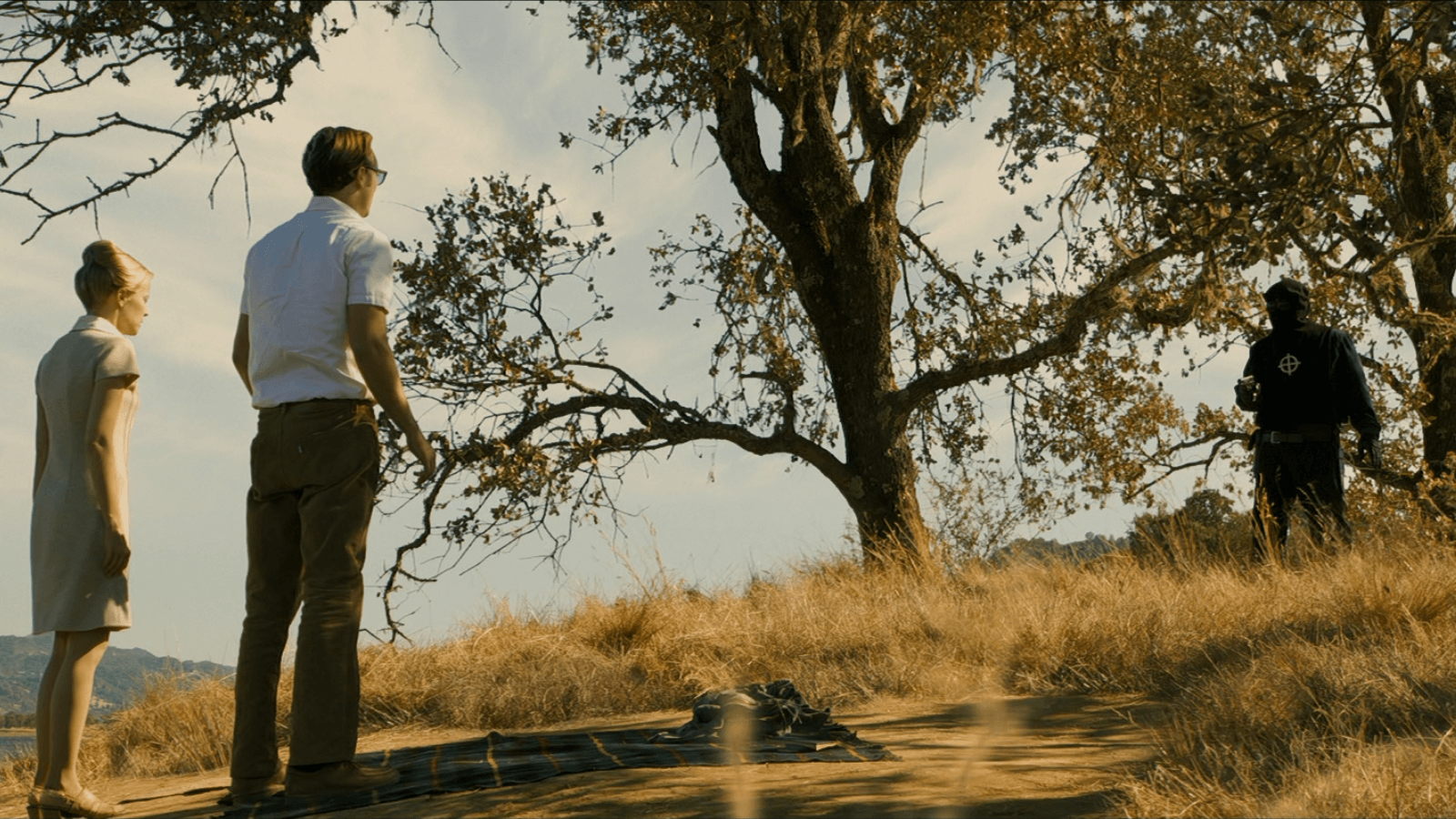

As suggested, Fincher’s visual style is restrained in Zodiac—far less expressive than his earlier work, but also more sophisticated in his methodical approach. Consider just the attack on September 27, 1969, in Napa County at Lake Berryessa. Fincher turns a lakeside getaway with two Pacific Union College students, Bryan Hartnell (Patrick Scott Lewis) and Cecelia Shepard (Pell James), into a horrifying, unforgettable scene. Appearing in a black hood bearing the crosshairs Zodiac symbol, a figure claiming to be an escaped convict interrupts the two and announces plans to rob them. He ties the two up, but rather than take their money, he begins stabbing them. However, Fincher does not cut around the penetration of knife into flesh like the implied stabbings in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1968); he shows the force of the Zodiac’s body, the impact of the knife, and Shepard’s hair-raising screams. We cannot imagine their horror and pain as their attacker leaves them to inscribe his symbol on their car, parked up the road, and then later call in his anonymous confession. Somehow, Hartnell survived the attack. Shepard was not so lucky. Our fascination with true-crime becomes a matter of our equal measures of terror and curiosity about the truth of Zodiac: Terror derives from the horrible reality of these crimes, which Fincher shoots in unforgiving, meticulous detail. None of the murders shown onscreen were filmed without surviving witnesses providing the filmmakers essential details. Knowing Fincher’s adherence to such precise filmmaking makes the film’s murder sequences even more visceral and, as much as cinema can provide, real. Fincher’s obsession is tantamount to Graysmith’s or the countless amateur sleuths who voraciously consume true-crime podcasts and documentaries.

Our curiosity is another matter altogether. Curiosity sends Graysmith sniffing where he shouldn’t more than once. Indeed, Zodiac‘s most suspenseful scene leads to a red herring. Following an anonymous tip that the Zodiac is Rick Marshall, a projectionist at a vintage movie theater that screened The Most Dangerous Game, the cartoonist investigates the theater’s original movie posters, supposedly hand-drawn by Marshall. Morrill confirms the posters show the closest match yet seen of the Zodiac’s handwriting, except for his Ks. Graysmith’s research leads him to the home of Bob Vaughn (Charles Fleischer), a theater organist whose music accompanies silent movies. Graysmith follows a tip that Vaughn is storing a film reel for Marshall, purportedly containing evidence of a Zodiac murder. During their conversation, Vaughn says he drew the movie posters, not Marshall. All at once, Graysmith, drenched wet from the storm outside, realizes that Vaughn makes a far better suspect than Marshall. Vaughn invites Graysmith into his basement to find records of when The Most Dangerous Game screened and if it corresponds with the murders. Standing in a dank, dripping basement among shelves of old film reels with his now prime suspect, Graysmith hears footsteps upstairs. Could it be Marshall? Vaughn insists he lives alone. More footsteps. Were Vaughn and Marshall accomplices in the Zodiac killings? The moment is heart-stopping. It’s all Graysmith can do to rush upstairs, grab his things, and run for his life out the front door.

Fincher’s elaborately shot murder sequences and subtle technical genius underscore the intricacy of the case at the center of Zodiac, but this is also an extremely funny film at times. Avery’s character allows Downey, Jr. to display his signature wit, egoism, and sarcasm in a role before his repopularization in the Marvel Universe. Ever likable, Ruffalo makes Toschi’s eccentricities amusing, such as his need for animal crackers in the car. Edwards delivers expert deadpan in his responses to some of the hundreds of interviewed crackpots claiming to be the Zodiac. But much of the humor revolves around Graysmith’s introverted characteristics and how well Gyllenhaal uses his youth to accentuate the characters’ blind innocence. Arriving at the office one day, Graysmith asks The Chronicle‘s coffee man Shorty (James Carraway), “Does it ever bother you that people call you ‘Shorty’?” Without missing a beat, Shorty fires back, “Does it ever bother you that people call you ‘retard’?” Gyllenhaal’s face goes pale, “Nobody calls me that…” and walks away. In the next scene, Graysmith brings Avery a coffee and, clearly feeling sensitive, asks, “Does anyone ever call me names?” Avery shoots back, “You mean like ‘retard’?” “Yeah,” says Graysmith. Avery looks at him, “No.” More than just a humorous aside, the scene demonstrates Graysmith’s outsider status at the paper—something of a weirdo who fixates on the Zodiac case. With his infatuated personality, Graysmith might have developed into a role not unlike Gyllenhaal in Nightcrawler (2014), if not for the character’s rigid moral backbone.

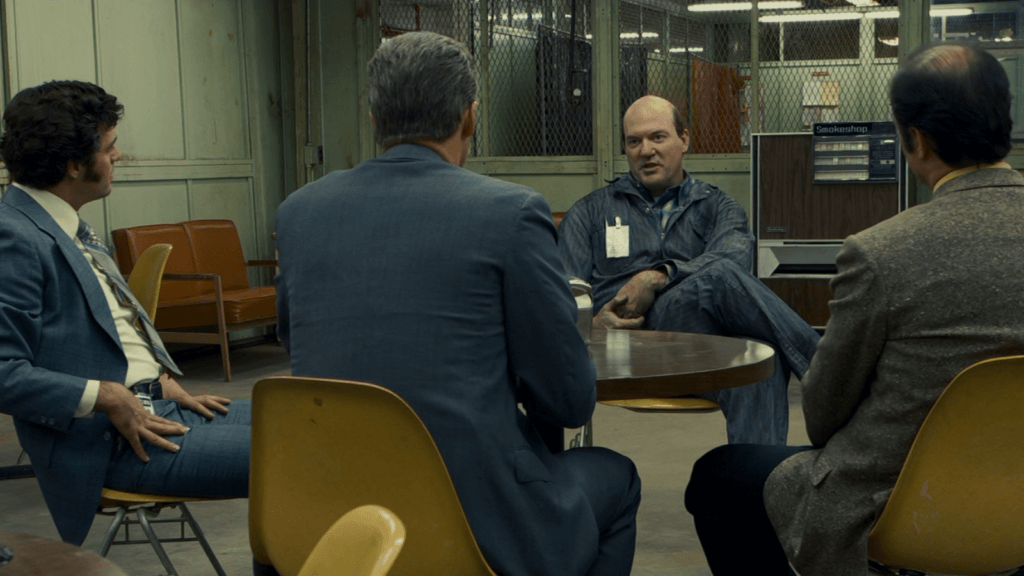

Though moments of suspense are relieved with humor at times, a sense of urgent tension floods Zodiac—a feeling purveyed by the filmmaking and a strong case against a single suspect, yet how those involved can do nothing to detain him. Graysmith and Toschi believe Arthur Leigh Allen was the Zodiac. Graysmith’s books build the case against him in incredible, convincing detail. Most of the evidence against him was indirect or circumstantial, however, as we discover when Toschi, Armstrong, and Vallejo detective Jack Mulanax (Elias Koteas) interview Allen. During the interview, they notice Allen wears a Zodiac-brand wristwatch, the only place where the crosshairs symbol and the word “zodiac” appear together, outside of the killer’s letters. Allen admits that when he was questioned after a murder, he told an officer that he had bloody knives in his trunk because he had slaughtered some chickens. He wears the same size military-grade boot matching an imprint found at one crime scene. He had an earlier conviction for child molestation. He even told a former coworker about a plan to kill people and write letters to the police, signing the letters as “Zodiac.” What for the audience and detectives is a smoking gun, the eerie scene in the film results in a thin case from a prosecutor’s perspective. No warrant can be obtained to search Allen’s home, and due to a handwriting sample that doesn’t match the ambidextrous Allen, the investigators are, quite frustratingly, forced to pursue other leads, leaving the audience to deem the entire Zodiac case a sloppy, logistical nightmare, and ultimately a portrait of the often ineffectual nature of the criminal justice system.

And yet, without the finality of the case being closed, the Zodiac lingers. The available evidence (some concrete, some less so), Allen’s behavior under questioning, and most importantly their instincts tell the film’s viewer Allen is the Zodiac. But Toschi isn’t Dirty Harry, a character that, along with Steve McQueen’s role in Bullet (1968) and Michael Douglas on the TV series The Streets of San Francisco (1972-1977), was based on Toschi. He cannot follow his instinct, show up at Allen’s Fresno Street home, and put a bullet in his head. This is true-crime, not an escapist Hollywood production. What it comes down to is cold, hard, unromantic evidence. Not until 1991, when new evidence had mounted, did authorities consider making an arrest. Bombs had been taken from under Allen’s home, survivors Mike Mageau (Jimmi Simpson) and Don Cheney (John Hemphill) both implicate Allen, and countless other clues all lead to Allen as their man. Alas, Allen died of a heart attack before any such arrest could be made. Nevertheless, Graysmith and Toschi believe Allen was the killer. In some sense, Fincher adopts the position of Graysmith’s books and ends the film with the belief that Allen was the Zodiac Killer. But that’s all it is—a belief. It is not known. Graysmith (and thus Fincher) provides a resolution to the mystery through the law of irrefutable inference. As Bob Woodward says in All the President’s Men, “If you go to sleep at night and there is no snow on the ground, and you wake up in the morning and there is snow on the ground, then you can be pretty sure that it snowed overnight.”

In another sense, Zodiac is very much open-ended, quite intentionally so. As he weaves a complex network of clues, case details, and uncertain feeling about suspects for his audience and investigators to ponder, Fincher implants an undercurrent of ambiguity, which grows within the viewer and festers there. At the very moment Zodiac seems to solidify its stance that Allen was the killer, a postscript offers another seed of doubt about Allen’s DNA that grows, rankles, and leaves us unsatisfied, albeit by design. There is no closure, no arrest, no return to our safe little world. And how frightening it is, not knowing with absolute certainty who killed those people and sent those letters—frightening and even maddening. To that extent, Zodiac operates in the same way that Blow-Up (1966) and The Conversation (1974) established uncertainties they refused to resolve to any satisfactory degree. Attributing Zodiac’s murders becomes impossible once you consider that he’s attempting to break his pattern, and thus skew the investigation, by claiming responsibility for other crimes he possibly did not commit. Fincher’s loyalty to the detail of Graysmith’s books may offer a potential solution, but the film’s most essential characteristic is how the director so effectively manipulates our certainty, or lack thereof, and roots obsession. Through this, we develop an understanding of the now-relatable investigators and their flaws. Apart from Armstrong, who knew when to walk away, the investigators in the film are not noble heroes; they sacrifice their families and jobs for a burning desire to continue searching. The investigators could be guilty of fishing for connections because they want Allen to be the killer. When one witness remembers someone thought to be named “Rick,” she clarifies that it was more like “Leigh,” and Graysmith cannot help but assume the name refers to Arthur Leigh Allen. Zodiac‘s level of closure depends on what we feel to be true, as opposed to what we can prove.

What remains unambiguous about Zodiac is the need for finality among the characters, how some can walk away without a need for closure, while others are haunted by a mystery that can never be solved. This obsession leads to a sense of nihilism toward all else, another common trait of Fincher’s characters from Det. David Mills to Tyler Durden, from Mark Zuckerberg to Nick and Amy Elliott-Dunne. Fincher exercises that same nihilism in his obsessive treatment of the film’s mystery, in that characters’ lives are less important than the case. Of course, the same is true for the characters in the film—Graysmith’s wife leaves him, Toschi’s wife grows tired of how the case has consumed him, and Avery loses himself to substance abuse while clinging onto the celebrity the case brings him. Emotional sacrifices in the pursuit of some ideal leave a scar on these characters, and by association, and through Fincher’s expert direction, they also leave a scar on the viewer. More than a visually pristine formal presentation, more than his visibly or thematically dark material, Fincher’s films are about characters who suppress their deeply felt emotions. Alien 3 (1993) had Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley fighting a hopeless battle, while suppressing her feelings of loss over her surrogate daughter; Morgan Freeman in Se7en laments the harsh city and how it tears a person down, which he’s experienced first-hand; in The Game, Michael Douglas’ introverted millionaire is forced to acknowledge traumas he’s long since buried. The comparisons could go on endlessly, but only Zodiac‘s scar aches long afterward the way few other Fincher titles do.

How fitting that Fincher, ever the obsessive, with a notorious history of requiring multiple takes and afflicting his meticulous attention to detail onto his cast and crew to get what he wants, made his best film about obsession. Like a contagion that festers as easily as it spreads, Fincher’s methodical Zodiac is catching. Pursuing the case today becomes an exercise in practicing unquenchable thirst, even for the most accomplished true-crime aficionados. And so, the film revels in details, intentionally incomplete details, and yet never feels like a documentary or anything less than a stunningly shot and acted motion picture. Through dead-end leads, inconsistent testimony, inconclusive data, varied opinions on the meaning of certain evidence, and only one real suspect, Arthur Leigh Allen, the film recreates our need to know, with any amount of certainty. All extraneous detail has been removed from the screen. In one sequence to represent the passage of several years, the viewer watches a black screen and hears vintage news reports and bulletins on major events over the period. Fincher and Vanderbilt applied a dogged attention to detail through which facts are real, clues are authentic, and every time-stamped scene is significant, as though Zodiac now serves as a summary of evidence from a police file. Through Fincher’s master manipulation, we become so wrapped up in the discovery, details of the investigation, and how these fascinating characters are consumed by it, that we not only understand but share the horrible incompleteness of the case’s investigators. He infects the audience with that need to know. Indeed, Zodiac may have procedural elements, but it’s about obsession and the lingering sense of dissatisfaction—over the case, not the film—that stays with you long after its final frames.

Bibliography:

Browning, Mark. David Fincher: Films that Scar. New York: Praeger, 2010.

David Fincher: Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. Laurence F. Knapp (Editor). University Press of Mississippi, 2014.

Maillard, Florence. David Fincher: Masters of Cinema. Phaidon Press, 2015.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review