I, Tonya

By Brian Eggert |

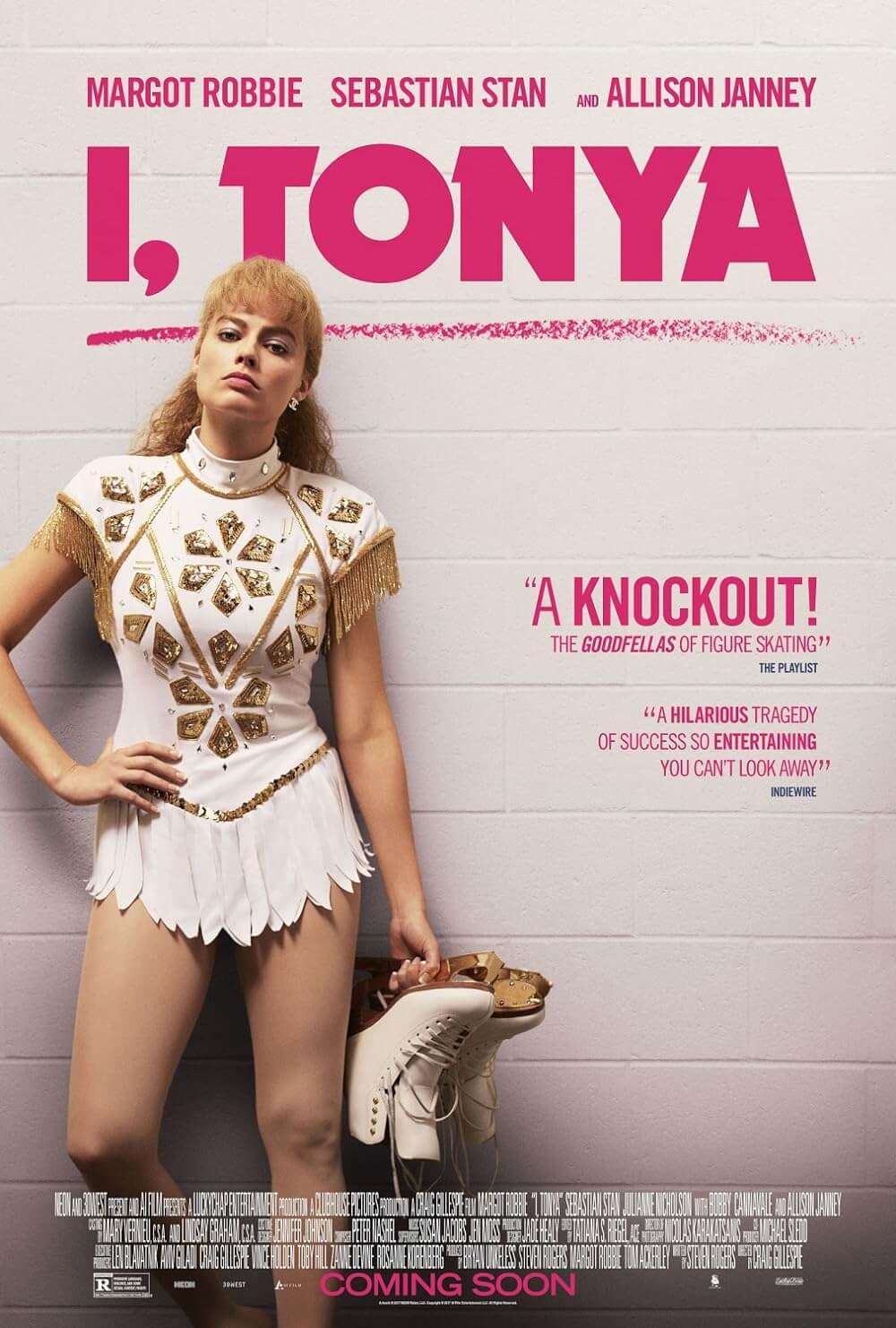

“America,” muses Tonya Harding, “they want someone to love, but they want someone to hate.” In the infectious black comedy I, Tonya, Margot Robbie plays the disgraced American figure skater who, in the 1990s, achieved global infamy after being blamed for the knee-capping of her Olympic rival Nancy Kerrigan. Tonya became a villain to some, an anti-hero to others, but made headlines everywhere. Here, she’s portrayed as having the makings of an Olympic princess, but with all the tact of a backwoods survivalist. Nevertheless, Robbie, deglamorized for her role in frizzy hair and gaudy homemade costumes (none of which make her look like Tonya Harding, but no matter), delivers an outstanding and surprisingly empathetic performance. Craig Gillespie, the journeyman director behind the 2011 Fright Night remake and The Finest Hours (2016), treats these real-life characters with humanity, even while some of Tonya’s behavior, and the behavior of the people around her, border on caricature. More than a scurrilous and nostalgic tell-all of a wild 1990s scandal, Gillespie assembles an entertaining and often hilarious film about a failed underdog, and in doing so, critiques both the American media and public for manufacturing a pariah.

Based on actual “irony free, wildly contradictory” interviews, the film begins with a series of faux docu-style testimonials to establish the cast. Set 20 years after the 1994 attack on Kerrigan, the interviews find Tonya long since forgotten. She recalls her lifelong abuse from loved ones, beginning at the age of three when she aspired to become a figure skating champion. Even into early adulthood, the physical and psychological torment carried out by her monstrous mother (Allison Janney, fantastic) seemed normal. Janney’s performance, expertly shifting between passive-aggressive and just-plain aggressive, results in treatment so horrible that the viewer feels guilty for occasionally laughing. One such moment occurs when, in the midst of a typical domestic argument with tossed dishes, a projectile knife sticks into Tonya’s arm. I, Tonya has a way of balancing the comic moments with serious, shocking ones that draw us into Tonya’s corner.

As the train of abuse continues with Tonya’s first love, Jeff Gillooly (Sebastian Stan), whom she marries, it’s tempting to consider her blameless for what follows. “It’s not my fault,” she insists over and over again. And yet, somewhere between her impressive talent and sordid connections, Tonya seems to orchestrate her own professional demise. Most of the film’s second half concerns the planned psychological warfare on Kerrigan (via threatening letters) that descends into a physical assault. Hatched by Jeff, who quickly becomes Tonya’s ex-husband, and her so-called bodyguard, the oafish pathological liar Shawn Eckhardt (Paul Walter Hauser), the plan falls apart and becomes utter madness. Shawn is little more than a misguided-if-loyal crackpot who, existing in a bubble conceived from his own imagination, believes he’s an international spy (nevermind that he lives at home with his parents). Although Robbie dominates the screen in the film’s first half, Stan takes center stage later as Jeff desperately tries to keep the situation under control.

Throughout the film, Gillespie returns to the characters in their interview mode to offer commentary on the proceedings, many of them remarking on the media coverage. That is, after all, the method through which most Americans “experienced” this story. Alongside the O.J. Simpson trial, the Menendez murders, and Lorena Bobbitt’s unique brand of revenge, the Harding-Kerrigan scandal was some of the most talked-about tabloid fodder of the 1990s. Although Tonya allegedly had little to do with that notorious attack, referred to only as “The Incident” in the film, such details were unimportant to the media. Tonya’s life was sensationalized. She was turned into a punching bag, a national joke given her tomboyish “white trash” roots and penchant for skating to ZZ Top songs. And despite her evident talent (she was one of the first figure skaters in history to land a triple axel in an international competition), she was regularly told by others that she did not belong in such refined, upper-class company. Though there’s a class commentary available to screenwriter Steven Rogers, he touches on this theme only briefly, favoring a sharp look at the media and American sensationalism instead.

At the same time, I, Tonya walks a fine line and, occasionally, risks becoming the very thing it despises. Critical of the media that hounded her and made her “the second most famous person in the world, after Bill Clinton,” the film nonetheless pokes fun at the sillier, more “redneck” aspects of her life. For example, when getting back into shape for the 1994 Winter Olympics, Tonya runs through the woods near her home with sacks of dog food on her shoulders, flips logs, or carries gallons of water on a pole—an odd choice of workouts for a figure skater, to be sure (she has modeled her training regimen after Rocky Balboa). But this training montage is interrupted by Tonya’s coach Diane Rawlinson (Julianne Nicholson), who looks into the camera with a Can you believe this? expression and says, “She really did this.” It’s difficult to reconcile whether Gillespie has embraced the so-weird-it-must-be-true aspect of Tonya Harding’s story, or if the material itself is just hyperbolic without any need of exaggeration. Every time we begin to suspect that Tonya is the author of her own downfall with her crass behavior and poor choice of associates, something happens to suggest her victimhood. Take Bobby Cannavale’s Hard Copy producer, who admits to flattening the tires on Tonya’s pickup to have it towed if only so the reporters camped outside her house could snap a few photos.

Regarding the film’s presentation, Gillespie borrows from Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990) playbook to conjure the frenetic energy required for much of I, Tonya. The highs and lows of romance and domestic abuse between Tonya and Jeff, and the paranoid scenes after the Kerrigan attack involving Jeff’s frantic race to maintain control, echo Scorsese’s iconic treatment. Fast camera rushes, multiple narrators (some of whom break the fourth wall), and a playlist of overused film soundtrack selections mark Gillespie’s derivative style. And so, perhaps more accurate comparisons are David O. Russell’s American Hustle (2013) or Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997), both shot in the Scorsese style. Like Russell or Anderson’s films, there’s an undeniable touch of irony in Gillespie’s uses for characters who, as referenced earlier, present themselves without irony. Just like Dirk Diggler or Irving Rosenfeld, Tonya is talented but a little pathetic, while those around her prove sleazy, rotten, and awful. Our empathy overcomes the film occasionally treating her like a joke, investing us in Tonya’s story, even while her indirect culpability remains clear. Regardless, her final sentencing, which banned her from competitive figure skating for life, seems unfair and cruel (and far worse than the jail time served by her cohorts)—just another example of a judge trying to bring media attention to their court with extravagant sentencing, as opposed to assigning a punishment that fits the crime.

If I have taken too much of a censuring tone in this review, it’s only to emphasize that viewers of I, Tonya may experience mixed emotions about the story and how it’s structured. That, as it turns out, is the point. But the performances throughout the cast have been associated with awards talk, which is entirely justified. And the filmmaking, while reminiscent of better directors, is also confident and expertly delivered. Tonya is a complicated protagonist, and the film doesn’t wholly take her side. The result is one part Tonya’s personal truth of the events, one part reveling in junk food news, and another part media critique. Still, the joys of this film should not be understated. Throughout, Gillespie and Robbie, who also produced, firmly place the viewer on Tonya’s side, even after moments where her testimony might be doubted. Much like Tonya herself, the film bears a lot of contradictions. She becomes a sympathetic figure who speaks to the audience and reminds us, through our culture’s continued obsession with tabloid media, “You’re all my attackers.” And with that, we cannot help but feel shame for being glued to the coverage back in 1994, or strangely culpable for enjoying I, Tonya as much as we have.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review