Mank

By Brian Eggert |

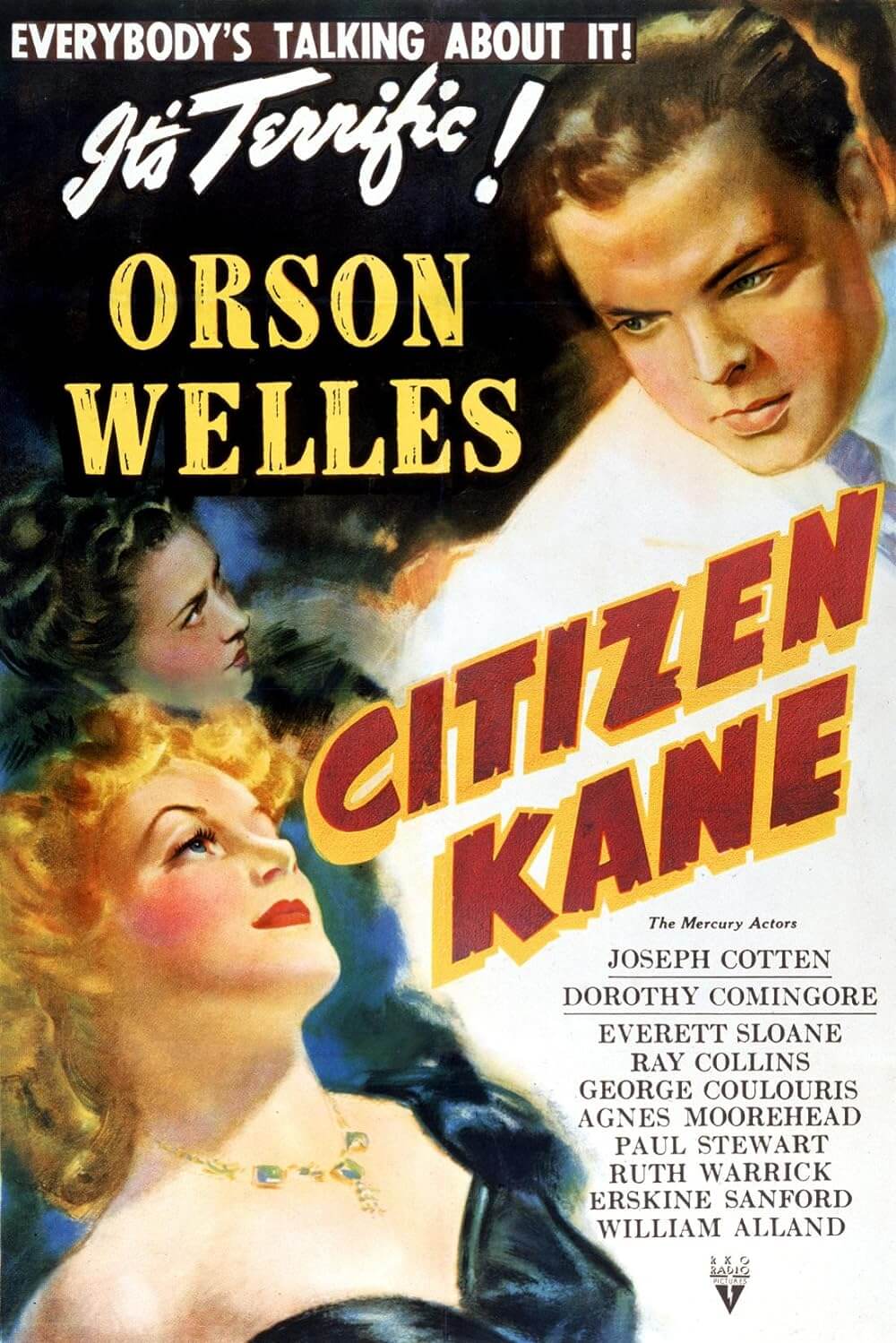

Mank should not be called “a love letter to Classic Hollywood,” as many reviewers have described it. That’s like calling 2010’s The Social Network a love letter to Facebook; it represents a gross misunderstanding of the text. Although the director of both films, David Fincher, shows what makes these enterprises alluring, he’s more interested in what corrupts them. In the earlier case, it’s a single man, an entrepreneur whose ambitions stem from hubris, envy, and petty revenge. Fincher’s latest, Mank, refers to screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, a New York drama critic who becomes a functionary in the Dream Factory, an industry that, since the beginning, has been in the business of mercilessly carving art into commerce. On the surface, the film details Mankiewicz’s role as author and credited co-writer of Orson Welles’ masterpiece Citizen Kane (1941), which he famously wrote as a takedown of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. But the screen story also cuts into the power-brokering rampant in 1930s Hollywood, where the men like Hearst, who controlled the media and thus the public’s access to certain information, could sway popular opinion and change the outcome of elections. Though it’s shot in black-and-white, looks like a classic film at first glance, and takes place in a distant past, Mank feels decidedly relevant today.

Fincher connects his film’s setting and the present visually, combining aspects of Golden Age Hollywood with more contemporary stylistic flourishes. Working alongside cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt and production designer Donald Graham Burt, Fincher creates a monochrome image that evokes the past—complete with an old-fashioned title sequence and a fantastic throwback score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross that adds a peppy contrast to the utterly cynical screen story. Messerschmidt shoots using digital cameras, not film stock, and yet creates pristine images that occasionally show artificially implanted specs, along with faux cigarette burns that denote the changing of a (nonexistent) reel. The presentation does not employ the boxy Academy Ratio, the standard screen size of the day, but rather unfolds in a widescreen format not widely used until the mid-1950s. Mank neither replicates a classical mode nor aligns with how films are made today. It resolves to be a curious amalgam of both styles, in effect linking how the culture of the 1930s and 1940s bears similarities to the here and now.

Mank was written by Jack Fincher, the director’s father, a screenwriter whose projects (such as a Howard Hughes biopic that was folded into 2004’s The Aviator) never materialized in life (he died in 2003). He had written Mankiewicz’s story in the 1990s; though, it’s doubtful that Hollywood at the time would have greenlit a film that changed the usual narrative around the making of Citizen Kane—that Welles had taken on Hearst in a David and Goliath conflict and come out victorious, as depicted in the rousing 1999 HBO film RKO 281. Fincher’s screenplay suggests that Welles represents another kind of “dog-faced” Goliath, albeit smaller in stature than Hearst, and took undue credit for the screenplay. It’s an old debate, started in 1971 when critic Pauline Kael published a lengthy essay called “Raising Kane” that questioned Welles’ contributions, upsetting many in the process, not the least of whom was Peter Bogdanovich, Welles’ devoted subject. Kael’s claims were discredited in a 1978 counterpoint essay Robert L. Carringer called, “The Scripts of Citizen Kane.” Incidentally, Fincher’s screenplay received some doctoring from Eric Roth (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button), uncredited of course.

Mank was written by Jack Fincher, the director’s father, a screenwriter whose projects (such as a Howard Hughes biopic that was folded into 2004’s The Aviator) never materialized in life (he died in 2003). He had written Mankiewicz’s story in the 1990s; though, it’s doubtful that Hollywood at the time would have greenlit a film that changed the usual narrative around the making of Citizen Kane—that Welles had taken on Hearst in a David and Goliath conflict and come out victorious, as depicted in the rousing 1999 HBO film RKO 281. Fincher’s screenplay suggests that Welles represents another kind of “dog-faced” Goliath, albeit smaller in stature than Hearst, and took undue credit for the screenplay. It’s an old debate, started in 1971 when critic Pauline Kael published a lengthy essay called “Raising Kane” that questioned Welles’ contributions, upsetting many in the process, not the least of whom was Peter Bogdanovich, Welles’ devoted subject. Kael’s claims were discredited in a 1978 counterpoint essay Robert L. Carringer called, “The Scripts of Citizen Kane.” Incidentally, Fincher’s screenplay received some doctoring from Eric Roth (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button), uncredited of course.

The screen story features Gary Oldman as Mankiewicz, who, after a car crash, must work on his script, originally titled American, while confined to bed at a ranch in Victorville, California, away from his wife and children. Welles (Tom Burke) occasionally calls to check on his progress; otherwise, Mankiewicz is alone with a personal secretary, Rita (Lily Collins), who takes dictation, and a German nurse (Monika Gossmann) to care for him—both hired by Welles’ collaborator John Houseman (Sam Troughton). A notorious drunk, Mankiewicz laments his stay in the “dry house,” where Welles has replaced the writer’s whiskey stock with Seconal that, imbibed before bed, will put the writer to sleep before he can cause any damage. In other words, from the opening scenes onward, the story is not about the protagonist falling into alcoholism or emerging triumphant for having written a masterful script. Mankiewicz is and remains a tragic figure who never changes. Somehow, he lucks out by collaborating with Welles, the Mercury Theater wunderkind who negotiated a final cut deal with RKO on any project of his choosing—and he chose Mankiewicz’s thinly veiled portrait of Hearst. But no other director could have facilitated Citizen Kane or seen it to the finish line.

Most of Mank takes place in flashbacks, remembered from Mankiewicz’s place in bed, that illuminate how the screenwriter’s relationship with Hearst and other Hollywood elites went sour. It starts in 1930 when Charles Lederer (Joseph Cross) accepts Mankiewicz’s invitation to Hollywood to become a screenwriter. Lederer enters a writers’ room that includes Ben Hecht, among others (including an unexplained topless secretary with tassels on her nipples), and together they improvise a horror movie pitch to Paramount executive David O. Selznick and director Josef Von Sternberg (referencing Universal’s The Wolf Man over a decade too early). Mankiewicz will soon impress Hearst (Charles Dance), whose mistress, Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), works for Paramount. He becomes a regular fixture at Hearst’s dinner parties, where Mankiewicz drinks too much and speaks with an unfiltered, witty, but acerbic tongue. In a scene sharply edited by Kirk Baxter, MGM head Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard) and the isolationist Hearst dismiss the looming Nazi threat and the socialist politics of author Upton Sinclair (Bill Nye, in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it appearance), while other party guests keep their protests measured. Not Mankiewicz—his cynicism, ego, and intellect refuse to be silenced, as if they’re scheming to destroy him.

Alternating between Mankiewicz’s progress on America and his memories about Hearst and Davies that inform it, Mank could be mistaken for a film about politics, given the vital role California’s 1934 gubernatorial election plays in crushing the screenwriter’s faith in Hollywood, if it ever existed. Conservatives like Hearst and Mayer back Republican Frank Merriam, whereas Mankiewicz wants to see Sinclair’s calls for tax reform and pensions become a reality. Backed by Hearst’s media empire, Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley) and others at MGM distribute highly produced propaganda newsreels to discredit Sinclair, cinching the election. Though Mankiewicz always knew members of the Hollywood brass were snakes, he’s shocked at just how poisonous they can be. Coming out of four years of Trump’s America and the era of “fake news,” the audience can no doubt relate. Moreover, the theme of corruption from on high in 1930s California cannot help but recall Chinatown (1974), complete with an untouchable mogul and a hero in over his head.

Alternating between Mankiewicz’s progress on America and his memories about Hearst and Davies that inform it, Mank could be mistaken for a film about politics, given the vital role California’s 1934 gubernatorial election plays in crushing the screenwriter’s faith in Hollywood, if it ever existed. Conservatives like Hearst and Mayer back Republican Frank Merriam, whereas Mankiewicz wants to see Sinclair’s calls for tax reform and pensions become a reality. Backed by Hearst’s media empire, Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley) and others at MGM distribute highly produced propaganda newsreels to discredit Sinclair, cinching the election. Though Mankiewicz always knew members of the Hollywood brass were snakes, he’s shocked at just how poisonous they can be. Coming out of four years of Trump’s America and the era of “fake news,” the audience can no doubt relate. Moreover, the theme of corruption from on high in 1930s California cannot help but recall Chinatown (1974), complete with an untouchable mogul and a hero in over his head.

Sure enough, it’s the beginning of the end for Mankiewicz’s role as a bitter jester in Hearst’s court, and Oldman, who is terrific, plays rock bottom in uncomfortable, exhilaratingly acted scenes. From Mankiewicz’s obliterated idealism, his usual propensity for self-destructive gambling and drinking accelerates, and he lashes out at everyone, even Davies, at an excruciating but thrillingly captured dinner. Of course, we never see Mankiewicz in a flattering light. At times he’s funny, even somehow endearing in his scenes with Rita—a character so wholesome and good that she seems like a writerly device designed to engineer empathy for Mankiewicz. But whatever good graces he may have established with the viewer come spilling out onto Hearst’s marble floor. Fortunately, Hearst is the sort of figure who uses a cruel allegory about the organ grinder’s monkey to describe Mankiewicz, reminding us that, no matter how awful Mankiewicz behaves, he’s preferable to Hearst.

Mankiewicz is another in a long line of complicated, oftentimes disagreeable protagonists to lead a David Fincher film. Seven (1995), Fight Club (1999), Zodiac (2007), The Social Network, and Gone Girl (2014) each center on downright unpleasant people who inhabit even more unpleasant worlds. The maligned genius appeals to Fincher for obvious reasons: he’s a perfectionist director who obsesses over every detail. His meticulous, virtuoso presentation is only matched by his reputation for pushing actors to the brink with his insistence on take after take, sometimes reaching into the hundreds. Such control-freak behavior might drive another studio batty, but Fincher has found Netflix’s loose oversight and patience rewarding. In addition to producing shows like House of Cards, Mindhunter, and Love Death + Robots, the director recently signed a four-year deal with the streaming service to make additional features. The point is, Mank is a personal film for Fincher that would never have been made under different circumstances, and for that, it should be celebrated as a rarity.

The unfortunate reality about Mank is that its main character proves to be such a challenge to the viewer’s empathy that watching the film is hardly a joyful experience. It doesn’t need to be pleasant to be valuable as art, but it helps to have someone to root for. Mankiewicz’s intelligence and humor only distract from his self-annihilation so much. More than once, his wife (Tuppence Middleton, miscast as a woman twice her age) is asked why she stays with him, and her response that life with her husband isn’t boring proves unsatisfactory. Doubtless, Fincher intends to offer a portrait, not unlike that of Charles Foster Kane, whose trajectory from an idealist to a defeated and solitary man represents a memorable dramatic arc. However, Kane had personality and charm, especially in his scenes of youthful exuberance; when we first meet Mankiewicz, he’s already half broken. There’s no Rosebud, no halcyon days. Mank simply finishes the job of shattering its protagonist. It’s a complex portrait that’s ripe for analysis, but it did not stir passionate emotions in this reviewer.

But there’s no denying that Mank is a film to be admired for its craft, albeit with cold, objective appreciation. Messerschmidt creates beautiful imagery with a milky sheen and unquestionable polish, while Fincher offers a number of playful sequences, among them retro-style montages. Oldman, too, gives a technically brilliant performance. If there’s any real fault here, it’s that Mank undervalues how Mankiewicz started working from a 300-page draft written by Welles and continued to collaborate with both Welles and Houseman. So when he accepts his Oscar for Best Screenplay outside of his home, Mankiewicz declares, “I am very happy to accept this award in Mr. Welles’ absence because the script was written in Mr. Welles’ absence,” it ignores the intricate collaborative process that led to Citizen Kane, evidenced in production notes uncovered by historians like Carringer. Historical quibbles aside, this is a confident production whose theme about the difference between messages created by artists and messages controlled by corporations resonates in today’s industry, where filmmakers often work for multinational conglomerates. Fincher’s film, both on and off-screen, represents an example of a triumphant artist telling a personal story, and that continues to be a rare thing.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review