The Definitives

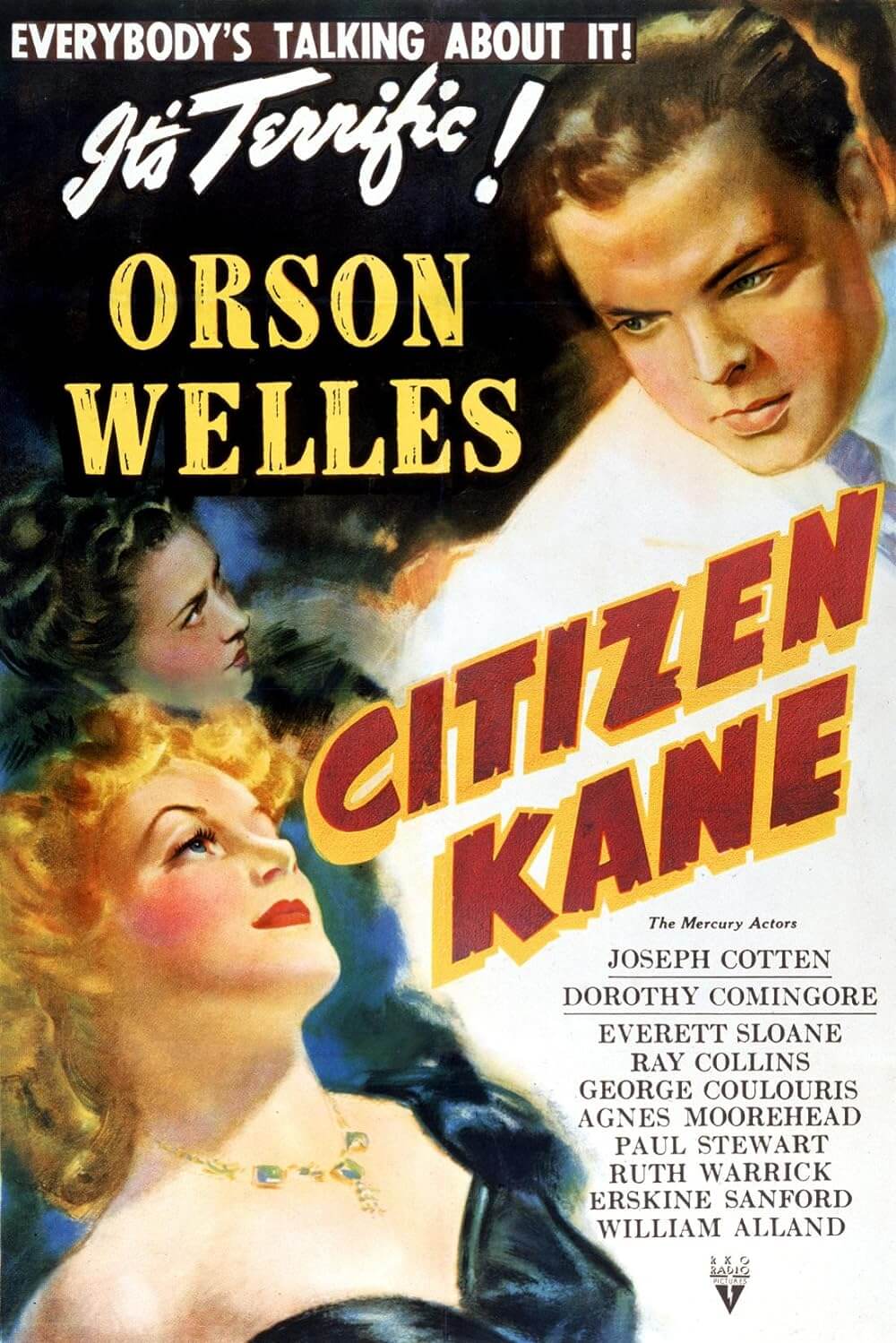

Citizen Kane

Essay by Brian Eggert |

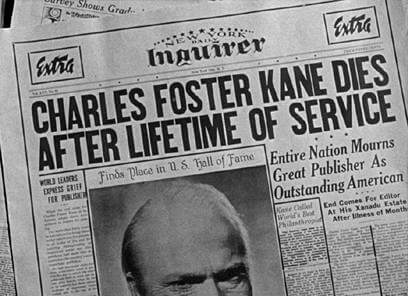

Just as the newspapermen in Citizen Kane set out in vain to find “an angle” on which they can evaluate the subject of Charles Foster Kane’s death, approaching Orson Welles’ motion picture today might be equally futile. The film has been endlessly explored and investigated, researched by countless film historians, analyzed by top scholars, while biographers have found many links between Welles, Kane, and newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, the figure on whom Kane was based. For the last several decades, these exhaustive assessments have resolved that Welles’ picture is cinema’s finest treasure. Through the film’s story, its production and tumultuous release, and the biographical strains therein, Citizen Kane has been described as a work of art imitating life and life imitating art. What more can be said by academics, cinéastes, or critics? The investigation of Welles’ picture is no less complicated than the one in the film, wherein the crucial component is “Rosebud,” the word uttered with Kane’s dying breath, and the missing piece of his life’s jigsaw puzzle. What is it, and could one word really define a human being so succinctly? “It’ll probably turn out to be a very simple thing,” remarks one of the reporters. Indeed, although the secret of Rosebud is a revelation given to the audience alone, its disclosure is illusory, less a key than a missing piece in a larger complex of puzzle pieces, and should any one of them go missing, the picture would be just as incomplete. Just as it is for the reporters in the picture, it’s the investigation of Citizen Kane itself that has meaning and sustains its legend.

The story of Citizen Kane’s journey to the screen is a fascinating exploration into art, business, and politics, steeped with biographical insight about the parties involved, namely Hearst, but especially the burgeoning talent of Welles. By the time RKO Radio Pictures released the film in 1941, Citizen Kane had defied the controversy and scandal around its production, barely survived destruction at the hands of competing studios and threats issued by Hearst, and represented an unprecedented achievement in Welles’ body of work, one that could never be matched over the next four decades of his career. Box-office dispassion sealed the film’s reputation until, after Hearst’s death in 1951, a reassessment began that declared Welles’ picture one of the greats, a film that would long be associated with unchallenged hyperbole about its importance and status as “the best motion picture ever made.” And while the film itself is undeniably significant, above all in its technical breakthroughs and narrative innovations that expanded film as an art form, it is the film’s story that has cemented its legacy. Welles’ film avoided destruction and was later hailed as a masterpiece, perhaps the finest masterpiece in all of cinema. This represents an unprecedented triumph of the artist against the system, and therein lies the profound resonance of Citizen Kane.

A wunderkind and innovator of stage and radio, Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater company caught the eyes of Hollywood after his infamous radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’ classic The War of the Worlds broadcast in 1938 in a series of false news bulletins about a Martian invasion. The entire broadcast, complete with faux commercials, music and all, was designed by Welles for maximum believability. When listeners panicked and ran for the hills (some didn’t emerge until weeks later), Welles’ talent was cemented in the public consciousness. Soon after, RKO president George Schaefer offered Welles an extraordinary contract that entitled the untested filmmaker complete control over direction, script, production, and final cut over two motion pictures. Moving to Hollywood, Welles began to develop several ideas that never materialized, including a first-person take on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness where the camera would replace the protagonist, and also a British thriller called The Smiler with the Knife. But these ideas were far too small and not controversial enough for the boy wonder who had frightened thousands of listeners with his radio broadcast. Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz, an experienced screenwriter who entertained Welles with his tales of Hollywood’s early years, finally chose their subject when Welles discovered exhaustive notes for Mankiewicz’s unwritten book on Hearst. Mankiewicz had attended Hearst’s elaborate and star-studded parties as a Hollywood writer, and therefore had an inside view of Hearst’s life with his mistress, actress Marion Davies (Mankiewicz was friends with fellow screenwriter Charles Lederer, Davies’ nephew). For Welles, Hearst was ripe for exposure and, given the eventual script’s unabashed allusions to Hearst’s personal life, hidden behind the thin disguise of Charles Foster Kane, Welles was sure Hearst would retaliate. What he didn’t expect, however, was that the film would almost be destroyed in the process.

A wunderkind and innovator of stage and radio, Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater company caught the eyes of Hollywood after his infamous radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’ classic The War of the Worlds broadcast in 1938 in a series of false news bulletins about a Martian invasion. The entire broadcast, complete with faux commercials, music and all, was designed by Welles for maximum believability. When listeners panicked and ran for the hills (some didn’t emerge until weeks later), Welles’ talent was cemented in the public consciousness. Soon after, RKO president George Schaefer offered Welles an extraordinary contract that entitled the untested filmmaker complete control over direction, script, production, and final cut over two motion pictures. Moving to Hollywood, Welles began to develop several ideas that never materialized, including a first-person take on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness where the camera would replace the protagonist, and also a British thriller called The Smiler with the Knife. But these ideas were far too small and not controversial enough for the boy wonder who had frightened thousands of listeners with his radio broadcast. Welles and Herman J. Mankiewicz, an experienced screenwriter who entertained Welles with his tales of Hollywood’s early years, finally chose their subject when Welles discovered exhaustive notes for Mankiewicz’s unwritten book on Hearst. Mankiewicz had attended Hearst’s elaborate and star-studded parties as a Hollywood writer, and therefore had an inside view of Hearst’s life with his mistress, actress Marion Davies (Mankiewicz was friends with fellow screenwriter Charles Lederer, Davies’ nephew). For Welles, Hearst was ripe for exposure and, given the eventual script’s unabashed allusions to Hearst’s personal life, hidden behind the thin disguise of Charles Foster Kane, Welles was sure Hearst would retaliate. What he didn’t expect, however, was that the film would almost be destroyed in the process.

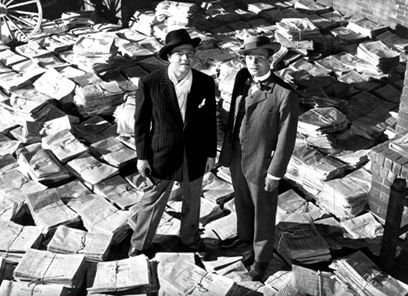

William Randolph Hearst was one of the most powerful, connected men in the United States, if not the world. A millionaire magnate whose “yellow journalism” tactics filled his publications with notes of scandal and the personal lives of politicians and movie stars, at his height, Hearst controlled almost thirty newspapers and magazines across the country, seen by upwards of 20 million readers. As such, he held significant influence over the media and public opinion. A larger-than-life figure, Hearst lived in the “Hearst Castle” in San Simeon, California, on a property reportedly half the size of Rhode Island, in a palace filled with a surplus of sculpture and artwork from around the world. At one point, he was responsible for twenty-five percent of the world’s art market, much of it sold at auction as the Depression wore on his empire. In spite of his status, he was not immune to scandal. Hearst’s newspaper editorials had, as believed in many circles, sparked an assassination attempt on President William McKinley; his Catholic wife refused him a divorce when he pledged his devotion to his long-standing mistress, Davies; he manipulated public opinion in favor of the Spanish-American War; when silent filmmaker Thomas Ince was shot aboard Hearst’s yacht and died in 1924, the scandal was covered up though it was believed a dispute between Hearst and Charlie Chaplin over Davies caused the notorious gunshot; and he was an ardent isolationist who thought the U.S. should not be involved in the looming World War II. For Welles, Hearst represented the antithesis of everything in which he believed. But he was determined to portray a sympathetic monster, while Mankiewicz viewed Hearst as a megalomaniacal figurehead to be decapitated.

After being expelled from Hearst’s circle for his excessive drinking, Mankiewicz harbored a deep hatred for Hearst, as evident in his initial script drafts, an unsentimental portrait then called American. Welles was forced to temper and organize the script, and how much he contributed to Mankiewicz’s original draft has long been a source of contention among film scholars and even those involved. However, Welles was famous for rewriting established material to suit his own needs, such as his stage revisions on Thomas Dekker’s The Shoemaker’s Holiday or his famously all African-American production of Shakespeare’s Macbeth set in Hati, nicknamed “Voodoo Macbeth.” But as early script drafts housed in the Lilly Library at Indiana University that predate American suggest, through Welles’ hand-written notes to Mankiewicz, the final screenplay was a joint effort on the part of both writers. Without the ego or the typical history-rewriting elaborations for which Welles would be attributed later in his career, Welles told the Times in London in 1969, “The initial ideas for this film and its basic structure were the result of direct collaboration between us.” Indeed, to humanize Kane, Welles fashioned parallels to his own life that had no equivalent in Hearst’s. When, as a boy, Kane’s mother sends him away to be raised by a bank (Hearst was raised by his mother), Kane is the same age as Welles when his idyllic childhood ended with his mother’s early death, leaving Welles to be raised by two ineffectual fathers (one adoptive, one biological) and a demanding school for boys.

Many aspects of Citizen Kane, such as Kane’s failure in politics and reckless spending, remain harsh indictments of Hearst and his lifestyle; so much so that Welles would later admit he felt the picture’s reflection and treatment of Davies was unfair. “Something of a dirty trick,” he called it. Dorothy Comingore plays Susan Alexander Kane, a bubbly singer whom Kane tries and fails to transform into an opera star. When her career bombs, she’s reduced to drinking and completing elaborate puzzles alone in Kane’s opulent estate, Xanadu, named after Kublai Khan’s summer capital visited by Marco Polo. Davies, a talented actress and comedienne who Hearst tried and failed to present as a dramatic performer, was likewise known for her puzzles and boozy ways. Furthermore, “Rosebud” was Hearst’s pet name for Davies’ private parts, and the significance of “Rosebud” on and off-screen dealt a particularly low blow to Hearst. But then there’s Xanadu, a vulgar description astoundingly not unlike the “Hearst Castle.” Xanadu first appears in the opening shots of Citizen Kane like a vampire’s castle, surrounded by fog, moats, and rowboats that resemble ferries meant for the river Styx. Contained inside is “the loot of the world”—countless statues, paintings, gargoyles, and stonework imported from exotic countries. Some of the pieces Kane has never seen; he just wants them for the sake of having them. Susan, too, is just an object in his collection. Everything is housed inside rooms so large that their vastness dwarfs their occupants. Exchanges between Kane and Susan in these rooms would have an almost comical effect if the scenes themselves were not rooted in such powerful drama, the two standing on opposite sides of a room, their voices echoing, their figures lost in the enormous spaces around them.

Citizen Kane’s most redemptive quality as it relates to its depiction of Hearst is that, aside from the occasional gross detail mirroring Hearst’s private life, Kane is a tragic, curiously sympathetic character. Kane is introduced in the film’s opening newsreel sequence, through which the course of his life is outlined for the audience. What’s lacking is “an angle,” says the newsreel editor, who assigns a reporter named Thompson, played by William Alland, whose face remains unseen, to investigate Kane and search for the meaning of Kane’s dying last word. What follows is a series of flashbacks told to Thompson by those close to Kane, moments where Kane shows his callousness or kindness depending on the subjective account. In the memoirs of the late Walter Parks Thatcher (George Coulouris), a banker and Kane’s guardian during his childhood, Thompson finds the story of a reckless, idealistic young adult with no interest in money, who is given vast wealth but instead chooses to develop a struggling newspaper. Joseph Cotten plays Jed Leland, Kane’s close friend who began by admiring Kane’s philosophy of honest journalism until he later witnesses Kane sell off his journalistic scruples. Through Leland’s eyes, Kane became an irredeemable monster bent on acquiring power and servicing his own ego, whereas Susan would remember the late Kane as a heartbreaking story, a man lost by want and desire that could never be fulfilled. In each case, the audience must consider the subjectivity of the narrator and question whether or not they are reliable. Certainly, there are subtle contradictions or gray areas about Charles Foster Kane in these accounts. They do not perfectly align like pieces of a puzzle into a full portrait of Kane, which is then finally made whole by our understanding that “Rosebud” was Kane’s childhood sled.

In filming the picture, Welles, an untested filmmaker with a genius status to live up to and therefore something to prove, tirelessly prepared his production and learned all he could about making motion pictures before Citizen Kane was officially green-lit. Though he was inexperienced, he instinctively grasped the juxtaposition of sound and image; he understood that several shots make a scene, multiple scenes make a sequence, and those sequences make a whole film. Achieving a flow between scenes and sequences, the technical aspects of the film and the narrative would result in a desired overall balance. Moreover, he concerned himself with layering technical elements—composition, acting, editing, makeup, dialogue, lighting, music, and narrative structure—with almost literary meaning, and as such, each element was rethought to put distance between Citizen Kane and other Hollywood productions. For a month before RKO greenlit the film, Welles shot test scenes to experiment in his new craft; when the heads of RKO saw this surprisingly polished test footage, they not only approved production but also used the tests in the finished film. On the set, Welles demanded a deviation from Hollywood normalcy and he jealously cast actors he could trust from his Mercury Theater company, including Cotten, Comingore, Coulouris, Everett Sloane as Kane’s financial manager Mr. Bernstein, Ray Collins as the corrupt politician Gettys, Paul Stewart as Kane’s snide butler, and Agnes Moorehead as Kane’s mother. Also from the Mercury Theater, he hired Bernard Herrmann (later the composer of many Alfred Hitchcock thrillers) to write the music. In a 1970 interview with Dick Cavett, Welles remarked, “I didn’t have anybody saying ‘You can’t do that!’ I just had a sort of pause and then, ‘Well, that’s never been done, but we’re gonna try it.’ So I had a marvelous spirit.” For example, he insisted that the sound editor not use RKO’s library of sound effects but instead create new audio effects for the film; he also insisted on expensive special FX sequences, usually filmed only once for cost purposes, be reshot several times to ensure the best results.

When it came to Welles finding a cinematographer, his choice was easy. Gregg Toland, John Ford’s cinematographer on The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home, both from 1940, made his way into Welles’ office and demanded that the young director hire him. “I want you to use me on your picture,” he said. “I want to work with someone who never made a movie.” To prepare, Welles and Toland studied Ford’s films—particularly Stagecoach (1939)—closely, as Welles had always been an admirer of Ford’s work. (Later on in his career, when he was asked to name his favorite directors, Welles famously replied, “I prefer the old masters, by which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.”) The walls of Welles’ office were covered with drawings and ideas about the visual presentation, but as Welles learned the craft of filmmaking, he quickly formed a desire to experiment within the medium. Together, Welles and Toland reinvented the cinematic wheel, employing no end of new camera tricks and unconventional devices. For the newsreel scenes, Toland shot on grainy stock and toyed with film speeds; to put objects in both the extreme foreground and distant background into focus, he used the split-diopter lens; he shot with an early shaky-cam format to imitate spy footage; when Welles wanted a lower angle than the stage floor could provide, they dug a hole in the concrete floor to get lower; and they avoided standard studio practices of close-ups and overhead lighting. They found ways to make what they wanted work on film, often experimenting not only for the sake of experimentation but also experimentation in which the innovative style reflected the purpose of a scene in a manner that had never been achieved before. Toland saturated the film in its signature deep focus photography, wherein everything within the frame was clear, and he shot scenes with ceilings for a sense of realism and to create unique lighting effects. French critic André Bazin once argued that deep focus enhances the uncertainty of a film because the camera’s focus doesn’t tell the viewer where to look, and so Welles and Toland leave the viewer to judge Kane by their estimation. Everything we need to know is up there on the screen, but we must decide where to look. Encouraged by how Welles welcomed a collaborative atmosphere on-set, Toland reciprocated and taught Welles everything he needed to know as a young filmmaker from the technical side. For his collaborative spirit and contributions, Welles gave Toland credit on the same title card as himself—a rare honor seldom bestowed in Hollywood.

When it came to Welles finding a cinematographer, his choice was easy. Gregg Toland, John Ford’s cinematographer on The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home, both from 1940, made his way into Welles’ office and demanded that the young director hire him. “I want you to use me on your picture,” he said. “I want to work with someone who never made a movie.” To prepare, Welles and Toland studied Ford’s films—particularly Stagecoach (1939)—closely, as Welles had always been an admirer of Ford’s work. (Later on in his career, when he was asked to name his favorite directors, Welles famously replied, “I prefer the old masters, by which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.”) The walls of Welles’ office were covered with drawings and ideas about the visual presentation, but as Welles learned the craft of filmmaking, he quickly formed a desire to experiment within the medium. Together, Welles and Toland reinvented the cinematic wheel, employing no end of new camera tricks and unconventional devices. For the newsreel scenes, Toland shot on grainy stock and toyed with film speeds; to put objects in both the extreme foreground and distant background into focus, he used the split-diopter lens; he shot with an early shaky-cam format to imitate spy footage; when Welles wanted a lower angle than the stage floor could provide, they dug a hole in the concrete floor to get lower; and they avoided standard studio practices of close-ups and overhead lighting. They found ways to make what they wanted work on film, often experimenting not only for the sake of experimentation but also experimentation in which the innovative style reflected the purpose of a scene in a manner that had never been achieved before. Toland saturated the film in its signature deep focus photography, wherein everything within the frame was clear, and he shot scenes with ceilings for a sense of realism and to create unique lighting effects. French critic André Bazin once argued that deep focus enhances the uncertainty of a film because the camera’s focus doesn’t tell the viewer where to look, and so Welles and Toland leave the viewer to judge Kane by their estimation. Everything we need to know is up there on the screen, but we must decide where to look. Encouraged by how Welles welcomed a collaborative atmosphere on-set, Toland reciprocated and taught Welles everything he needed to know as a young filmmaker from the technical side. For his collaborative spirit and contributions, Welles gave Toland credit on the same title card as himself—a rare honor seldom bestowed in Hollywood.

Welles and RKO agreed to keep the production under wraps in fear of inciting Hearst’s wrath; however, both the studio and their young director knew a battle over Citizen Kane would occur sooner or later. Rumor had begun to build that a film about Hearst was in production at RKO and, albeit indirectly, Hearst took action to suppress it. Devout Hearst loyalist and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper wrote in her column that RKO’s production of a film based on Hearst’s life has “become an industry affair and will be dealt with accordingly.” Hearst applied pressure to MGM head Louis B. Mayer with a threat to publically expose Hollywood’s top moguls as Jews in a seemingly unrelated smear campaign; Mayer, in turn, made an offer to RKO’s George Schaefer to buy all prints of the film for a reported $805,527 and change—just enough to cover the film’s costs. Schaefer refused the bribe. Welles, meanwhile, made his feelings on the subject well known in a statement to the press in which he alluded to the possibility of buying the prints himself and taking legal action against RKO: “Under my contract with RKO, I have the right to demand that the picture be released and to bring legal action to force its release.” Pressure from Welles and Schaefer convinced the RKO board to side against selling the film. Furthermore, Welles and Schaefer tipped the scales in their favor throughout Hollywood by arranging private screenings of Citizen Kane for many important filmmakers (including Frank Capra, John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and Ernst Lubitsch). Trusted men from the press were also invited to these screenings and used their influence to defend the picture. Time magazine wrote, “Hollywood [is] about to destroy its greatest creation,” and Newsweek writer John O’Hara proclaimed, “It is with exceeding regret that your faithful bystander reports that he has just seen… the best picture he ever saw… Reason for regret: you, my dear, may never see the picture.” With this, the Hearst-sympathizing Newsweek fired O’Hara.

Hearst attacked in other ways, such as refusing to carry advertisements or reviews for Citizen Kane, or any promotions whatsoever. Welles and Schaefer remained steadfast, and RKO finally released the picture in May 1941, the premiere held at New York’s RKO Palace on Broadway, with a slow expansion in the coming weeks and months. Box-office performance was hardly the splash everyone seemed to think it would be. Despite the controversy, the public was uninterested and received the picture with lukewarm attendance, regardless of its monumentally high critical praise and notes in the media about its bumpy road to the screen. Welles’ efforts went all but unnoticed at the time, exploding with a whimper. At the following year’s Academy Awards ceremony, Citizen Kane was nominated in nine categories, including Best Art Direction, Best Cinematography, Best Sound, Best Music, Best Editing, Best Actor, Best Director, and Best Picture. Only Mankiewicz and Welles would receive an award for Best Original Screenplay, while the majority of Citizen Kane’s nominations were lost to John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley. Nevertheless, the industry as a whole was divided in its assessment of both Welles and his contentious, dangerous film. Opinions about the young upstart Welles were evident whenever his name was mentioned during the Oscar ceremony and was greeted with boos. Still, among critics, the film was expected to sweep the Oscars; when it didn’t, Variety ran a headline afterward stating “Orson Welles’s Near-Washout Rated Biggest Upset In Academy Stakes.”

Rather than view him as a victim of Hearst’s bullying reign over the media, Hollywood saw Orson Welles as a dangerous, risky, and unbankable talent to have on the payroll. After Citizen Kane’s release, Welles spent a little over a year at RKO before the studio ejected him from their offices, and his reputation was solidified as an unemployable director. During this time, RKO renegotiated its contract with Welles and removed his final cut clause. Welles’ second production under his now revised RKO contract was an adaptation of Booth Tarkington’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), the film which the studio infamously took away from Welles in post-production, recut, and burned the edited-out footage. The subsequent film remains ingenious, but not Welles’ original vision; and since the excised footage was destroyed, the film may never be seen as Welles intended. Welles’ reputation after Citizen Kane, his unfortunate habit of losing his vision to meddling studio bosses, and his struggle to get financing on his independent projects would haunt him the rest of his career. In effect, he needed to start over. Citizen Kane wouldn’t be praised as “the greatest film ever made” for another fifteen or more years. And so, his mid-to-late career left him with the persona of an overconfident, independent genius without resources, desperately trying in his unique, bombastic way to secure funds for his latest project. Films like The Stranger (1946), The Lady from Shanghai (1947), Mr. Arkadin (1955), and Touch of Evil (1958) were each taken away and re-edited by intrusive producers. In some cases, the edited footage was not destroyed, and film historians, working from Welles’ detailed notes after his death in 1985 at the age of 70, could reassemble and restore Welles’ vision. In most cases, the original intent of these films has been altogether lost. Citizen Kane would be the only time in Welles’ career as a filmmaker where he set out and made his picture with complete artistic freedom.

Rather than view him as a victim of Hearst’s bullying reign over the media, Hollywood saw Orson Welles as a dangerous, risky, and unbankable talent to have on the payroll. After Citizen Kane’s release, Welles spent a little over a year at RKO before the studio ejected him from their offices, and his reputation was solidified as an unemployable director. During this time, RKO renegotiated its contract with Welles and removed his final cut clause. Welles’ second production under his now revised RKO contract was an adaptation of Booth Tarkington’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), the film which the studio infamously took away from Welles in post-production, recut, and burned the edited-out footage. The subsequent film remains ingenious, but not Welles’ original vision; and since the excised footage was destroyed, the film may never be seen as Welles intended. Welles’ reputation after Citizen Kane, his unfortunate habit of losing his vision to meddling studio bosses, and his struggle to get financing on his independent projects would haunt him the rest of his career. In effect, he needed to start over. Citizen Kane wouldn’t be praised as “the greatest film ever made” for another fifteen or more years. And so, his mid-to-late career left him with the persona of an overconfident, independent genius without resources, desperately trying in his unique, bombastic way to secure funds for his latest project. Films like The Stranger (1946), The Lady from Shanghai (1947), Mr. Arkadin (1955), and Touch of Evil (1958) were each taken away and re-edited by intrusive producers. In some cases, the edited footage was not destroyed, and film historians, working from Welles’ detailed notes after his death in 1985 at the age of 70, could reassemble and restore Welles’ vision. In most cases, the original intent of these films has been altogether lost. Citizen Kane would be the only time in Welles’ career as a filmmaker where he set out and made his picture with complete artistic freedom.

Every film historian and Orson Welles biographer has at one point asked the question: “What happened to Orson Welles after Citizen Kane?” Was his downfall self-propelled or was he a victim of an industry populated by enemies who felt threatened by his talent and his objective to elevate films to the rich and complex level of high art? No doubt, Welles formed Hollywood enemies who would never let up after the Citizen Kane affair. Very much akin to Charles Foster Kane, the story of Orson Welles’ career is a tragic one. In his appraisal of Citizen Kane, David Bordwell assessed the film in such a way that oddly describes Welles’ life as well: “…a tragedy on Marlovian lines, the story of the rise and fall of an overreacher. Like Tamburlaine and Faustus, Kane dares to test the limits of mortal power; like them, he fabricates endless personae which he takes as identical with his true self; and like them, he is a victim of the egotism of his own imagination.” Of course, this association links Welles to both Kane and Hearst, the three figures bloated by their character and self-indulgence. Hearst and Kane each accumulate an absurd amount of property and works of art, the excesses growing around them and overshadowing the individual. Welles, without the money to obtain vast collections or acquisitions, lived large nonetheless and transformed himself into a phenomenon as a human being—“a Dorian Gray in reverse” as Clinton Heylin observed. Welles traveled the world and enjoyed food and cigars; invariably, he was always the smartest person in the room. For his love of food, he grew outward, hidden behind his shockingly expanded frame, turning himself into a corpulent yet undeniable figurehead of his myth. Without the ability to buy a Xanadu for himself, he became the physical expression of his celebrity and used his public image to exploit that on which he fed: his legend. Both ironic and tragic, Welles, in a way, became the very thing he despised.

Biographers have tried tirelessly to understand what happened to Welles after Citizen Kane, just as film historians and critics have attempted to summarize the film itself. Some believe the film to be nothing more than a cautionary tale about the dangers of wealth and power; others think Welles made a deeply compassionate tragedy and character study. Although we can only speculate in our understanding of Welles, his only fully realized motion picture offers a singular key to unlock the mysteries of Charles Foster Kane. But “Rosebud” is less the final piece of the jigsaw puzzle that is Kane’s identity than a symbol of his indefinable humanity, a symbol which signifies how Kane is a man of, as Welles himself put it, “many sides and many aspects. It was my idea to show that six or more people could have as many widely divergent opinions concerning the nature of a single personality.” Citizen Kane is a complex story about the failures of a very big and powerful man, reflecting an equally powerful man, and told through the eyes of an artist of incredible talent. Contrary to what “Rosebud” intimates, it offers no direct answers and instead demands the process of investigation and reflection. In the last scenes, one of the men wandering through Kane’s treasures in Xanadu remarks, “I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life.” Aside from the film’s not insignificant storytelling and formal acumen, what it represents is far more important, both in terms of the film and in understanding Orson Welles. Bookended on Citizen Kane are shots of Xanadu’s gates on which a sign reads “No Trespassing,” and as the director of a film or author of a film analysis discovers, encapsulating an individual or artwork is not about jumping the gate to find a solitary answer, but gathering accounts, facts, and testimony and through them assign meaning. Perhaps the film’s most resonant quality is that, through the film’s story and production, Welles inspires the same investigative process about himself and his picture, forcing an awareness of how the film’s journey to find “an angle” results in a greater, far more intricate understanding.

Bibliography:

Bazin, André. Orson Welles: a critical view. Foreword by François Truffaut; profile by Jean Cocteau; translated from the French by Jonathan Rosenbaum. Harper & Row, 1978.

Benamou, Catherine L. It’s all true: Orson Welles’s Pan-American Odyssey. University of California Press, 2007.

Denning, Michael. The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. Verso, 1998.

Gilmore, James N., Sidney Gottlieb (editors). Orson Welles in Focus: Texts and Contexts. Indiana University Press, 2018.

Heylin, Clinton. Despite the System: Orson Welles Versus the Hollywood Studios. Chicago Review Press, 2005.

McBride, Joseph. Orson Welles. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996.

Thomson, David. Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles. Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter. This is Orson Welles. Edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum. Da Capo Press, 1998.

Wilson, Kristi M., and Tomás F. Crowder-Taraborrelli (editors). Film and Genocide. The University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review