Eternity

By Brian Eggert |

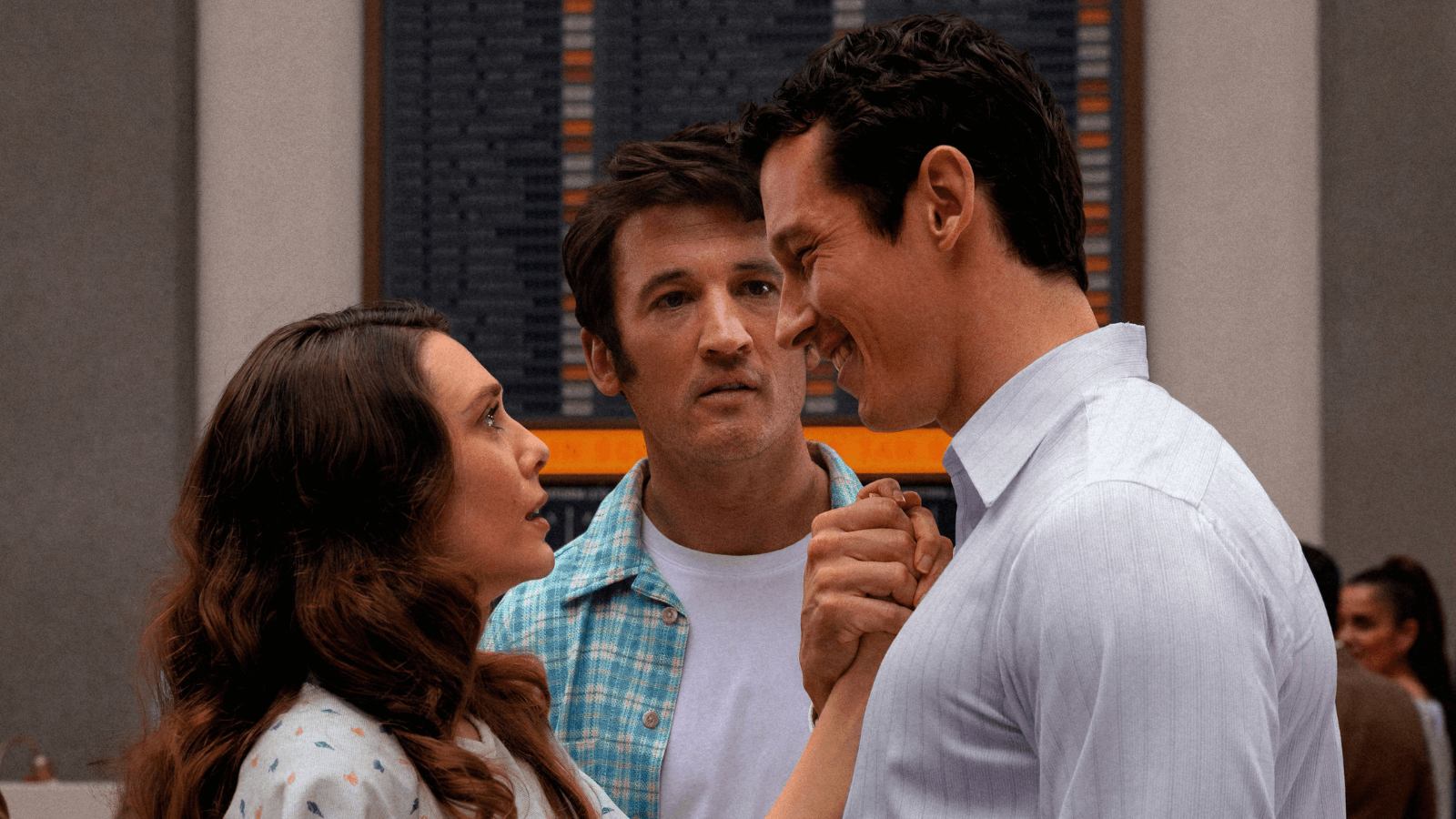

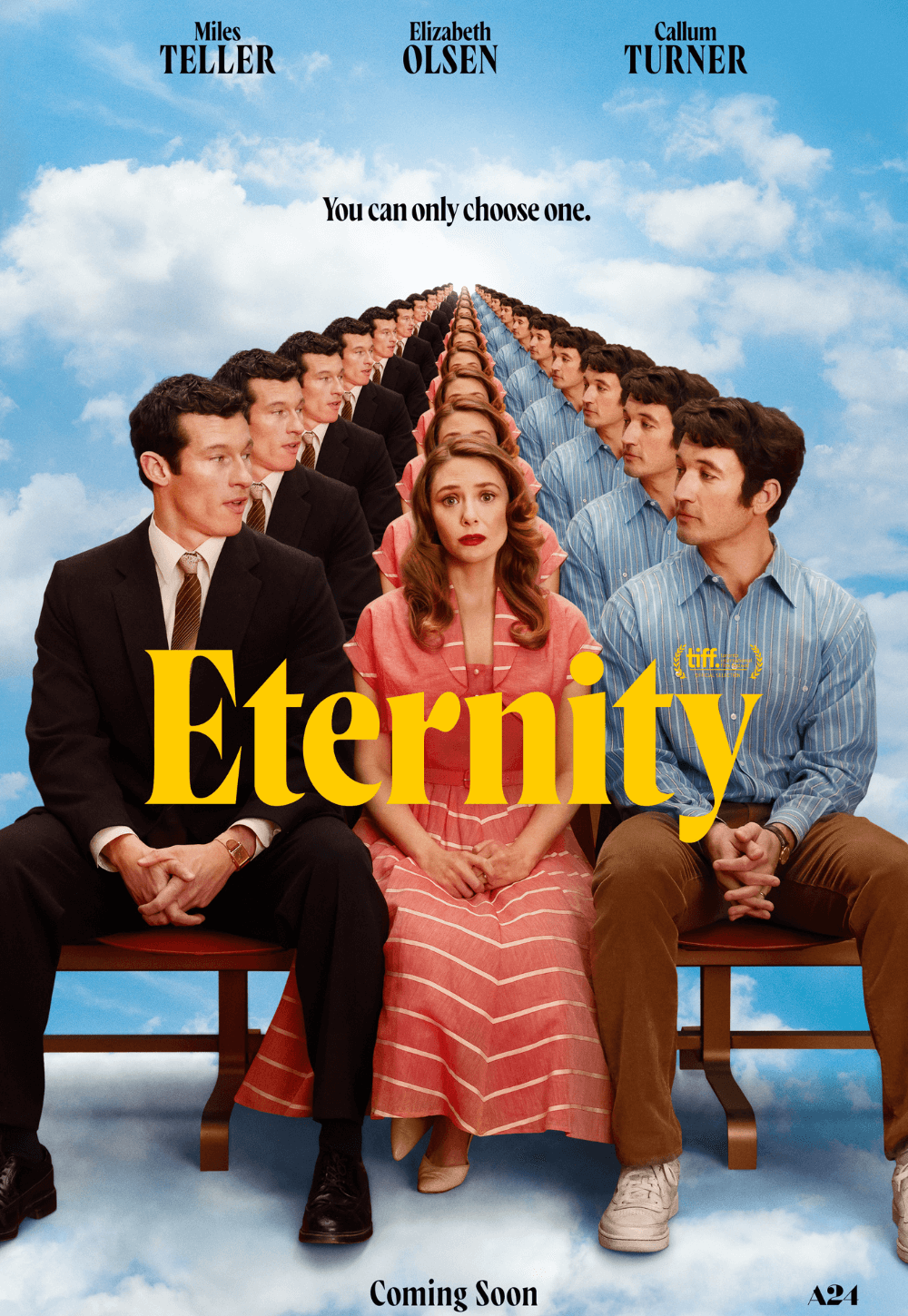

Upon arriving in the afterlife, Larry learns the truth: There is no heaven nor hell, no Valhalla nor Holy Mountain, nor River Styx that leads to Hades. Larry arrives at the soul’s transfer station, where he has seven days to decide the form of his Great Beyond. Although Larry, played by Barry Primus, died in his 70s, he materializes as his happiest self (Miles Teller) in this post-life junction. He hopes to reunite with Joan, his wife of nearly 65 years, played as a septuagenarian by Betty Buckley and as a younger woman by Elizabeth Olsen. But also waiting is Joan’s first husband, Luke, played by Calum Turner, who died in the Korean War and preferred to stay in this interim space to reunite with the love of his life. In Eternity, a high-concept comedy from director David Freyne (Dating Amber, 2020), Joan is faced with a question: With whom does she want to spend infinity? Luke, the so-called perfect man, whose love burns so passionately and with whom she never got the chance to build a life, or with Larry, with whom she did build a life, whose love is like a comfortable chair and a bowl of pretzels?

If any of this sounds vaguely familiar, that’s because Eternity borrows more than a bit of inspiration from Albert Brooks’ 1991 afterlife romance, Defending Your Life. Brooks conceived the afterlife as a weigh station where people are judged on whether they have overcome their fears enough to move on to the next phase of existence. While there, he falls in love with Meryl Streep. Who wouldn’t? Eternity‘s scenario, written by Freyne and Patrick Cunnane, presents a setup that doesn’t exactly replicate Brooks’ film, but it shares much of the same flavor. Note how people in Defending Your Life can visit the Past Lives Pavilion to glimpse their previous lives, while the characters in Eternity can visit the Archives, a vast hallway with diorama-like scenes from their lives, much like walking through their own personal natural history museum. In both films, the romantic climax involves a transport to their eternal realm and a desperate race for love. The comparison could go on, but you get the idea.

Setting aside Eternity‘s derivativeness, it remains a charmer nonetheless. It lacks the sly existentialism that Brooks infused into his effortless, heartwarming story about growing as a human being. But it’s a swoon-worthy romantic fantasy about a love triangle with unfathomable stakes. It’s also full of inventive ideas. For instance, everyone gets to pick their eternity. Whether you were a good person or a human piece of shit, you can select where you’d like to end up. And the options are many: You could choose Casino World, Library World, Weimar World (“With 100% less Nazis!”), or any number of other variations. I kept hoping to see Cinema World, but no such luck. When the newly dead arrive, they’re assigned an Afterlife Counselor, or AC, who helps them choose their eternity. If they can’t choose, they can opt to become a custodian at this interchange, maybe even become an AC. Luke never chose his eternity, preferring to wait for Joan. He’s been living as a bartender ever since, planning a series of romantic gestures and cornball lines to use on his wife, who hasn’t seen him since the 1950s.

The story unfolds in a four-act structure, and it begins to drag in the last two acts. The first three acts revolve around elaborate and fascinating world-building, followed by a temporary solution to Joan predicament. The film presents this in-between world as a kind of ’70s-era hotel hosting an afterlife conference, complete with vendors showcasing their various eternities in rinky-dink booths for an oddly all-American clientele. (Do other countries have their own afterlife realms? Or does everyone speak American English in death?) Once they select an eternity, a person cannot switch. Attempting to do so is forbidden and could land them in a black void forevermore. Much of the story also involves Joan trying to make a decision, with both Luke and Larry pitching her alongside their respective ACs, Ryan (John Early) and Anna (Da’Vine Joy Randolph). After Joan makes her decision, the film loses some of its momentum, even as it builds to a resolution that feels perfunctory yet unquestionably endearing.

While the question of Joan’s choice remains the narrative’s propellant, I kept asking myself, Why must she choose? Can’t they start a thruple? Maybe they should all live separate afterlives? But Freyne doesn’t have anything so unconventional in mind; he tells most of the story from Larry’s perspective, and that’s where our sympathies lie. Teller is at his most likable in the role, an old curmudgeonly soul inhabiting a younger body. Olsen is a pleasant presence as well, though there’s not much dimension to Joan. Turner didn’t impress me, though friends tell me he’s quite the heartthrob, suggesting that for some, his looks might make up for what Luke lacks in personality. Still, with these options, it’s not difficult to guess where Joan ends up, but it takes longer than one might expect for her to arrive at that destination, with some detours along the journey. More endearing is a subplot about Randolph’s character, whose afterlife has been dedicated to bringing others joy, and who finally finds some joy for herself.

With an ambition that appears to overextend its small budget, Eternity sometimes looks cheap due to its iffy CGI and dingy, Kaufmanesque spaces, brought to life by production designer Zazu Myers. That’s part of its idiosyncratic charm, with cinematographer Ruairí O’Brien shooting the film’s bureaucratic spaces in intentionally drab colors, while composer David Fleming’s vaguely Tati-esque score nods to the vintage banality of the afterlife. With all its imagination and conceptual intrigue, Freyne’s treatment resorts to predictable and familiar notes, such as a chaotic chase through memories, reminiscent of the one in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004). There have been better afterlife movies (see Pixar’s Soul, 2020) and even afterlife romances (see Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death, 1946). But this is a pleasant one, less for its vision and more for the strong work from the cast and genuinely romantic conclusion.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review