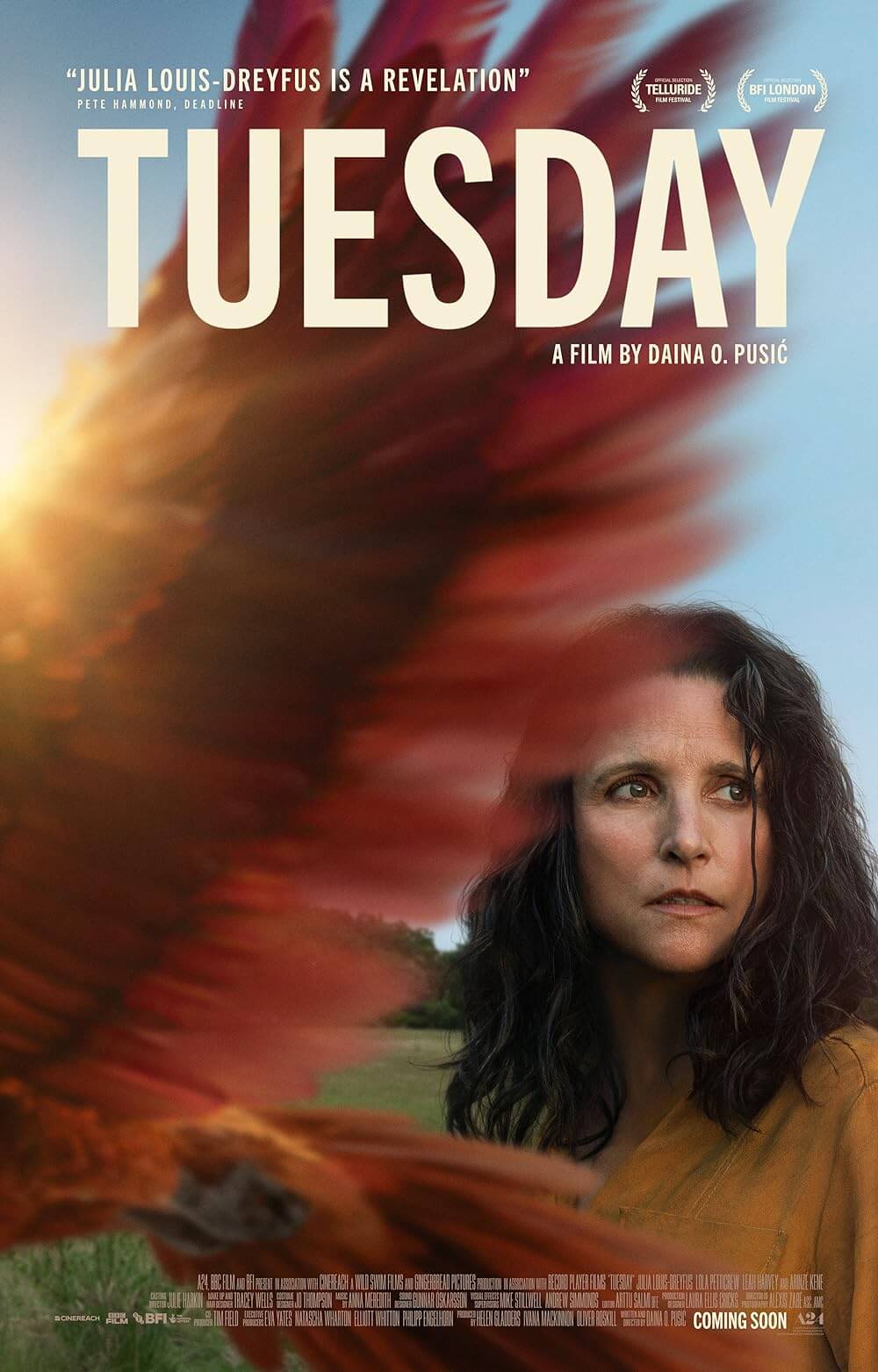

Tuesday

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally posted from the 43rd Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival on April 23, 2024. It has since been edited and expanded. The film arrives in theaters on June 14, 2024, via A24.

Death is a natural process. Yet, people spend so much time worrying about or denying the inevitable. For most of humanity, The End is so unfathomable that we have designed religions to avoid facing the grim reality. Elaborate afterlife scenarios quell the terror of our demise, allowing us to pretend that there’s another plane of existence, another realm, another life after this one. Death cannot be the end because, if it were, what would be the point? Rather than face those questions or accept that our lives are finite and not part of some grand scheme, that our place in the vast universe is not as significant as we might hope, we ignore the issue, try not to think about it, or invest ourselves in fantasies that invent a greater meaning. But with her debut feature, Tuesday, writer-director Daina O. Pusić grapples with death. Her film acknowledges that humans desperately resist accepting their fate, offering a tender portrait of denial, acceptance, and understanding of death that proves incredibly moving. The film also features another profoundly affecting performance by Julia Louis-Dreyfus, who plays a single mother forced to reconcile with the impending absence of her terminally ill teenage daughter, and continues to uncover layers of her talent.

An overwhelmingly heart-rending film, one that should be seen before learning anything about, Tuesday reconsiders death as a form of empathy and grace. On the surface, it might look like one of those schmaltzy terminal illness tearjerkers, ranging from My Sister’s Keeper (2009) to The Fault in Our Stars (2014). But it couldn’t be further from that. The first images have us considering celestial clouds and stars across the universe before settling in the scarred eye of a macaw that represents something like Death. In Pusić’s inventive, original conception, Death is a manner of psychopomp. This harbinger shape-shifts from a tiny form, small enough to nestle in a person’s ear, to a massive creature the size of a large mammal, depending on what the mood calls for. The image is a familiar one from Nature, but it’s subtly altered to suggest an otherworldly dimension. Plagued by the cries and whispers of people and animals in their final moments—arranged into an oppressive force by Gunnar Óskarsson’s expert sound design—the menacing figure hears the thoughts and pleas of those about to die. When the bird raises a red-orange wing blackened by time, the life ends, and then Death flies to his next stop. In this case, it’s the room of Tuesday (Lola Petticrew), who doesn’t have much time left.

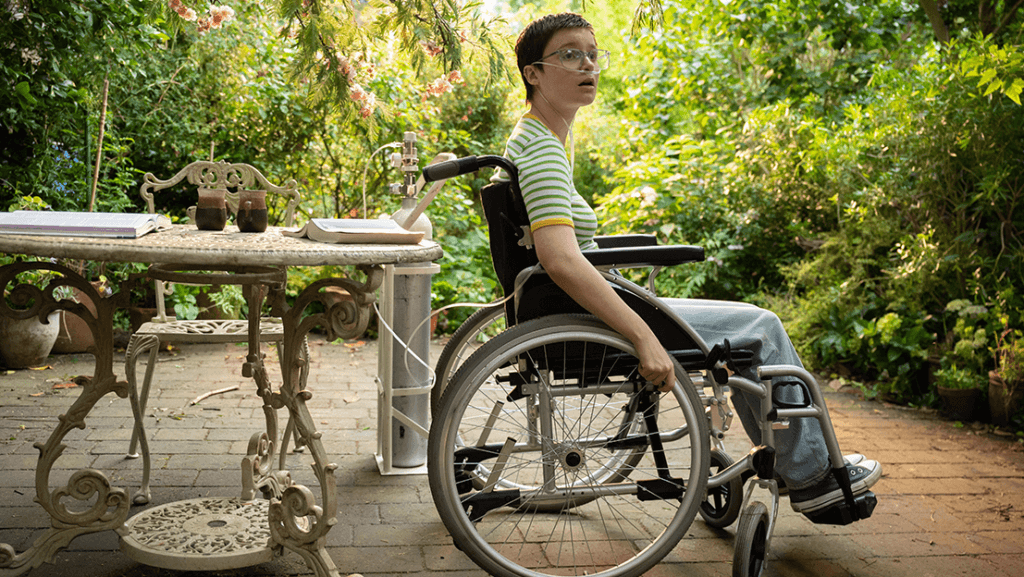

Louis-Dreyfus plays Zola, Tuesday’s mother, an American living in London whose life has become a perpetual state of avoidance. Though she once had a career, she has since left her job and spends her days compartmentalizing. She sits in the park, eating cheese and dozing off, or she pawns items from her home, such as a collection of taxidermied rats dressed to look like Catholic bishops. Her life has become defined by her refusal to talk about what’s happening to Tuesday. Zola literally tiptoes around the house to avoid her daughter, relying instead on a hospice nurse, Billie (Leah Harvey), to oversee her care. Zola cannot say goodbye; it hurts too much. But even Tuesday knows her time to achieve some closure has run out, especially after she encounters Death. The macaw flies into her bedroom to complete its job, but Tuesday pleads for a little more time for her mother’s sake. How do you convince Death not to take your life? With a joke, apparently. And when Death laughs, it sounds like a cartoon cereal box character in a stark contrast to its otherwise mirthless appearance.

Louis-Dreyfus plays Zola, Tuesday’s mother, an American living in London whose life has become a perpetual state of avoidance. Though she once had a career, she has since left her job and spends her days compartmentalizing. She sits in the park, eating cheese and dozing off, or she pawns items from her home, such as a collection of taxidermied rats dressed to look like Catholic bishops. Her life has become defined by her refusal to talk about what’s happening to Tuesday. Zola literally tiptoes around the house to avoid her daughter, relying instead on a hospice nurse, Billie (Leah Harvey), to oversee her care. Zola cannot say goodbye; it hurts too much. But even Tuesday knows her time to achieve some closure has run out, especially after she encounters Death. The macaw flies into her bedroom to complete its job, but Tuesday pleads for a little more time for her mother’s sake. How do you convince Death not to take your life? With a joke, apparently. And when Death laughs, it sounds like a cartoon cereal box character in a stark contrast to its otherwise mirthless appearance.

Tuesday’s unique mythology never distracts from the emotional immediacy of the mother-daughter relationship at the center, nor the surprising bond between Tuesday and Death. Still, it’s fascinating to learn more about how this version of Death operates and, moreover, relates to Tuesday with surprising tenderness. In its grunting, throaty voice, provided by Arinzé Kene, the bird confesses that it’s been a long time since he last spoke or interacted with a person in a meaningful way. Death agrees to give Tuesday some time to say goodbye to her mother but, in the meantime, the two form an oddly sweet rapport. Doubtless, Tuesday has had to care for her mother in a sense, having come to terms with her prognosis some time ago. She brings that same sense of caring to Death, offering a bath to clean its feathers and shielding him in her hands when loud music pummels its ears, prompting him to shrink down in a panic attack. “Always voices,” says Death in its grizzled voice, “begging me to kill them.” Lines like this could be creepy or monstrous, but there’s a sadness behind them that turns Death into a fleshed-out character, and a tragic one at that. “It hurts to feel myself exist,” he confesses.

Although Death’s voice could be considered anthropomorphism, its embodiment in a macaw suggests a different term—zoomorphism, perhaps? Regardless, Pusić’s conception of Death presents an alternative fairy tale, dusted with fantastic details, black-as-pitch humor, and a flair for the unexpected. The scenes between Death and Tuesday have an anything-can-happen quality to them, from the bird rapping and vaping to sharing stories about its mother: “A void of darkness.” And when Zola is confronted by her daughter, along with the entity that will take her daughter away, her reaction is priceless, hilarious, disturbing, and shocking all at once. Watching the film at the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival, the audience’s reaction ranged from sounds of disbelief, gasps of horror, and riotous laughter—all appropriate. And Zola’s response to Tuesday’s pronouncement, “I die tonight,” threatens to unravel the order of the universe. But when you love someone that much, there’s no limit to what you will do to protect them. Zola’s actions are unexpected, and their implications unfold during the remainder of the film in wildly creative ways best discovered without preparation.

In the press notes, Pusić attributes her attitude toward death to the “Balkan sensibility” of her upbringing, where a historically fraught culture developed a distinct sense of humor and acceptance about dying. Pusić studied film directing at the Academy of Dramatic Art in Zagreb, in her home country of Croatia, before moving to the UK to complete her education at the London Film School. She demonstrates an incredible control of tone in this sense. The balance between her film’s surreal comedy, mournful overtones, and often macabre details would be a challenge for even a skilled director, not to mention a first-time filmmaker. Aided by the assured, soft, and dreamlike cinematography by Alexis Zabé (The Florida Project, 2017), and the gentle pacing by editor Arttu Salmi who blends shots together in fluid, surreal transitions, Pusić imbues her film with a confident grasp of her magical realist ambition. Some viewers may interpret Tuesday as imbalanced, preferring to address death in a serious, practical, or traditionally religious way. But there’s a sophistication to Pusić’s concept and her view that death is not only necessary but a merciful act, even if there’s no “other side” or afterlife awaiting.

In the press notes, Pusić attributes her attitude toward death to the “Balkan sensibility” of her upbringing, where a historically fraught culture developed a distinct sense of humor and acceptance about dying. Pusić studied film directing at the Academy of Dramatic Art in Zagreb, in her home country of Croatia, before moving to the UK to complete her education at the London Film School. She demonstrates an incredible control of tone in this sense. The balance between her film’s surreal comedy, mournful overtones, and often macabre details would be a challenge for even a skilled director, not to mention a first-time filmmaker. Aided by the assured, soft, and dreamlike cinematography by Alexis Zabé (The Florida Project, 2017), and the gentle pacing by editor Arttu Salmi who blends shots together in fluid, surreal transitions, Pusić imbues her film with a confident grasp of her magical realist ambition. Some viewers may interpret Tuesday as imbalanced, preferring to address death in a serious, practical, or traditionally religious way. But there’s a sophistication to Pusić’s concept and her view that death is not only necessary but a merciful act, even if there’s no “other side” or afterlife awaiting.

Whatever bold moves Pusić makes that are bound to defy moviegoers who are entrenched in their ideas about death, the cast commits to the director’s varied wavelengths, delivering raw performances that keep the viewer in the moment. This is true even when the material becomes increasingly out-there, exploring what happens when Death isn’t around to wave his wing. Louis-Dreyfus has proven her skill as a dramatic performer for Nicole Holofcener in Enough Said (2013) and last year’s You Hurt My Feelings, but those are rather straightforward films by comparison. She’s never done anything so unconventional, and never with such a sustained ache. She captures the devastating emotional reality of preemptive grief in a revelatory performance. Her costar, the mostly unknown Petticrew, also delivers a memorable, aching, and brave character, relaying convincing scenes opposite their part-CGI, part-puppet costar, which never for a moment breaks the viewer’s immersion in this story. Of course, Death is a primary character as well, and Pusić often places the viewer in his perspective, allowing her audience to empathize with the thing many of us fear most.

Tuesday was backed by A24 Films and BBC Film, and there’s no telling how this production will fare commercially. Probably not well, since it’s not easily marketable. Wonderfully, the film resists categorization and fulfills a desperate hunger for original ideas and alternative perspectives. Some may feel frustrated by its many modes and refusal to be placed in a genre box, but that’s what’s so impressive and singular about Pusić’s execution. Her film explores themes that have been considered by other directors, writers, and poets, and it settles on a worldview—that the afterlife isn’t so much a real place as a memory preserved in those who love us—that remains familiar. But the details and humanity of Pusić’s storytelling have an emotional intelligence and vivid imagination that strike at the core of our existence. It’s a wonderfully realized and sensitive film about a woman who avoids facing death, and who must learn that death is not only a necessary function of Nature, no matter what awaits afterward, but also an act of compassion. And it’s anchored by Louis-Dreyfus’ astounding performance and Pusić’s singular vision, along with a sense of acceptance about death that is both mature and achingly powerful.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review