The Definitives

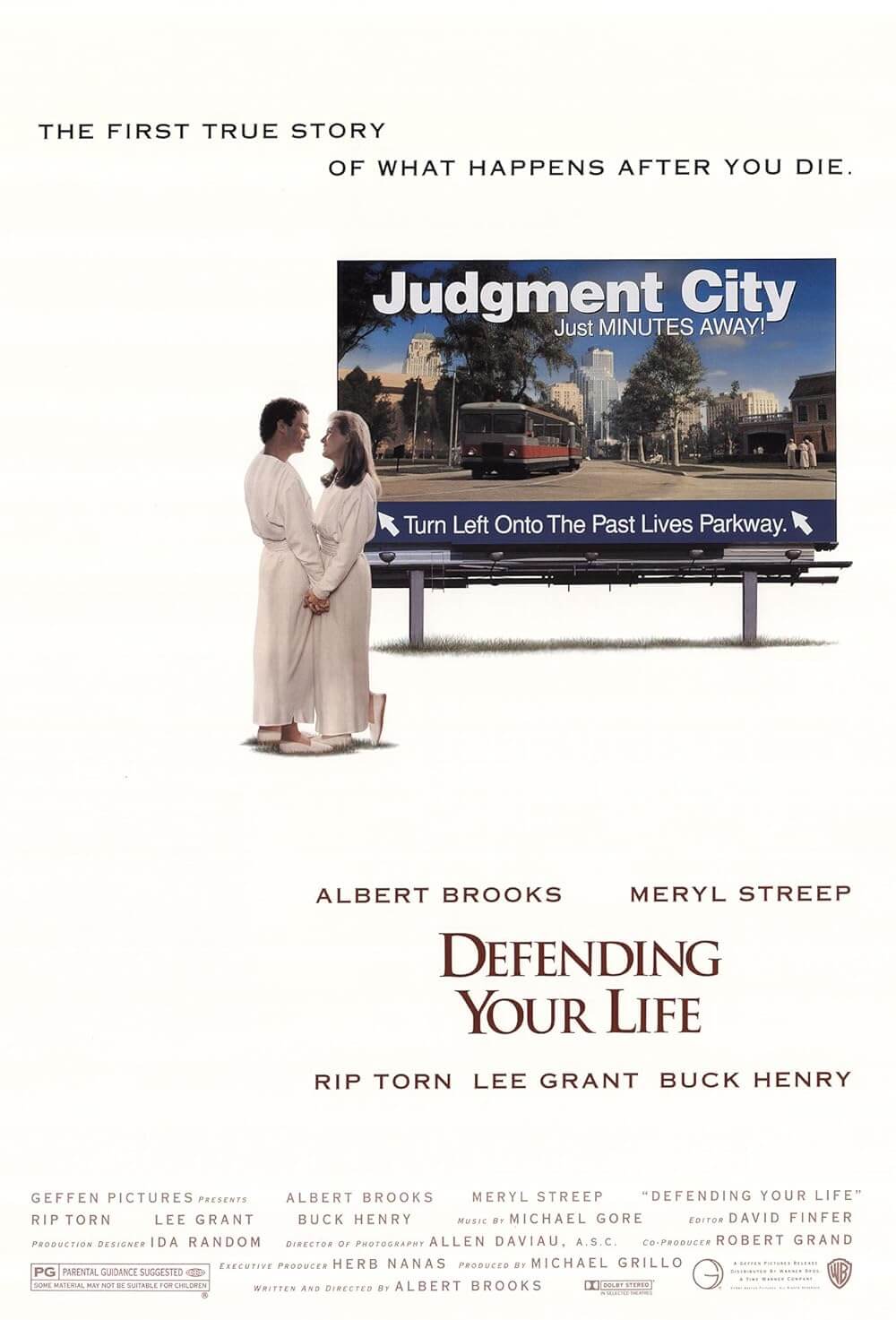

Defending Your Life

Essay by Brian Eggert |

(This essay was expanded from a review published on November 21, 2014.)

Albert Brooks’ Defending Your Life features one of the most intricately detailed and affectionately realized worlds ever created for a high-concept comedy. It’s the story of an afterlife not of puffy clouds and angels strumming golden harps, nor of a fire and brimstone netherworld ruled by a horned beast, but of writer-director Brooks’ imagination. The film posits a forward-thinking view of the universe where knowledge and self-improvement are valued above all else. Those who fail to make the most of their lives on Earth are not damned for eternity; rather, they can try again through reincarnation until they get it right (though there are limits). In Brooks’ film, life on Earth is about conquering the fear that forestalls you from evolving and having new, fulfilling experiences. And if his other films reveal anything about him, this sort of fear preoccupies the characteristically esoteric, mordant, and neurotic comedian and filmmaker. In Defending Your Life, before you pass onto whatever form of existence comes after this one, you must receive an official ruling that determines whether or not you have had a full and intrepid time on Earth. It’s the type of comic situation that Brooks, in his standard yuppie kvetcher role, uses to confront the universal inhibitions that prevent us from growing as people. And like most of his films, the scenario is hilarious, even as it compels us to look inward.

Out of all Brooks comedies, Defending Your Life has a much more optimistic outlook, despite the grim opening. In the pre-credits scenes, Brooks’ character, Daniel Miller, buys himself a BMW on his birthday. Life is good. He drives in cramped L.A. traffic, distracted and listening to his new Barbra Streisand CD—the song “Something’s Coming” no less—until he runs into a bus head-on and dies instantly. He emerges from a white light through silver doors, pushed in a wheelchair by a blue-scrubbed attendant down a long hallway and out onto a platform where he catches a tram to Judgment City, the universe’s pit stop. Wherever he’s arrived, it’s a place that “isn’t the Earth” but has been designed to appear familiar, thus a stress-free environment for its temporary inhabitants. Production designer Ida Random’s setting resembles Tativille, the metropolis Jacques Tati erected for PlayTime (1967), spliced with hints of 1990s-era business sectors. His tram stops at the Continental Hotel (the afterlife’s Holiday Inn), where he’ll stay for five days as judges review his life and determine whether Daniel will move on or try again on Earth. Clothed in a white, gownlike tupa, Daniel is told he can eat all he wants; binge eating will not affect his health—he won’t gain an ounce, and all of the food tastes delicious. The Weather Channel reports 74 degrees and “perfectly clear, all the time.” The makers of Judgment City have gone to considerable lengths to engineer this plane of existence to imitate the most pleasant, uncomplicated version of Earth, complete with every imaginable amenity.

After sleeping off his death hangover, Daniel wakes to a call from Bob Diamond (Rip Torn), his slick-as-snot defender whom he insists on calling his “attorney.” However, Bob maintains he’s not a lawyer (the role is a prototype for Torn’s producer Artie on The Larry Sanders Show). Bob explains that the purpose of life is “to keep growing, to get smarter, to use more of your brain.” Earthbound humans use only 3% to 5% of their brains, so they’re called “littlebrains” by the residents of Judgment City, most of whom use 40% to 60% of their brains. “I came from a world filled with penis envy to a world of brain envy,” Daniel remarks later in a great Brooks line. Bob will stand for Daniel against his prosecutor of sorts, Lena “the dragon lady” Foster (Lee Grant), and his case will be overseen by two judges (Lillian Lehman and George D. Wallace). They plan to view nine days from Daniel’s life, though most cases watch fewer; some, such as an adult book salesman Daniel meets, watch many more. And as Daniel explores Judgment City and explains to others how many days he’s looking at, he’s usually greeted by a sour expression of pity. But this is a pattern for Daniel, apparently. Bob explains that Daniel has gone through this process some 20 times before. “So I’m the dunce of the Universe,” Daniel observes. When he visits the Past Lives Pavillion to see some of his previous life experiences, he sees a former self as a tribesman running in terror from a lion.

After sleeping off his death hangover, Daniel wakes to a call from Bob Diamond (Rip Torn), his slick-as-snot defender whom he insists on calling his “attorney.” However, Bob maintains he’s not a lawyer (the role is a prototype for Torn’s producer Artie on The Larry Sanders Show). Bob explains that the purpose of life is “to keep growing, to get smarter, to use more of your brain.” Earthbound humans use only 3% to 5% of their brains, so they’re called “littlebrains” by the residents of Judgment City, most of whom use 40% to 60% of their brains. “I came from a world filled with penis envy to a world of brain envy,” Daniel remarks later in a great Brooks line. Bob will stand for Daniel against his prosecutor of sorts, Lena “the dragon lady” Foster (Lee Grant), and his case will be overseen by two judges (Lillian Lehman and George D. Wallace). They plan to view nine days from Daniel’s life, though most cases watch fewer; some, such as an adult book salesman Daniel meets, watch many more. And as Daniel explores Judgment City and explains to others how many days he’s looking at, he’s usually greeted by a sour expression of pity. But this is a pattern for Daniel, apparently. Bob explains that Daniel has gone through this process some 20 times before. “So I’m the dunce of the Universe,” Daniel observes. When he visits the Past Lives Pavillion to see some of his previous life experiences, he sees a former self as a tribesman running in terror from a lion.

Many films have tried to capture the afterlife onscreen. Most employ a faintly Christian view occupied by heavenly clouds, blinding light, and pearly gates, or alternatively, a mustachioed figure with a devilish appearance bent on the bookwork of acquiring souls. In the former category, consider Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946), where the living appear in Technicolor and the soul-processing bureaucracy of Heaven in black-and-white, epitomized by the film’s climactic court scene for the protagonist’s soul. Three years earlier, Ernst Lubitsch’s Heaven Can Wait featured Satan as a kind of bank executive obsessing over his inventory of souls. Such traditions have been kept alive throughout the subsequent years, all the way until Pixar’s Soul (2020)—a film that owes a great deal to Defending Your Life—in which the afterlife’s rule-bound accountants cannot content themselves with the jazzlike improvisations of the film’s hero. These examples are each about characters who yearn for more life on Earth and to delay the finalization of their death. Brooks offers a decidedly non-Christian and rather more sophisticated view. Daniel is not concerned about getting back to Earth or debating with his judges for more of his former life; the force compelling the universe is rushing headlong into the unknown to acquire more knowledge.

Whereas earlier models of the afterlife treat death and the Great Beyond as dreaded prospects, Brooks recognizes the importance of personal growth to move forward and considers death a positive experience. It’s a sentiment echoed by the NBC sitcom The Good Place (2017-2020), created by Michael Schur and inspired by philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Tim Scanlon, and conceptually informed by Brooks’ vision. “My father died when I was 11 years old,” Brooks told an interviewer. “I got some extra years thinking about, gee, where did Dad go? And I never liked that concept of heaven and hell—it was so black and white. One afternoon I thought to myself, Well, did we make all of this up? Maybe the universe runs a little bit like a corporation.” Similar to how the aforementioned films treat the afterlife with a businesslike structure, Brooks’ Judgement City depends not on an overarching morality or set of commandments but an opportunity for life advancement for people who proved on Earth that they could “take care of themselves.” To give his concept a motivating hook, Brooks chose the great equalizer—fear—as the measurement by which the universe judges human beings. As Bob Diamond explains, “Fear is like a giant fog. It sits on your brain and blocks everything: real feelings, true happiness, real joy.”

Brooks’ films so often deal with his depressive characters’ insecurities, nerves, and sense that they’re missing out, and this film puts his protagonist on trial for those traits. That he finds humor in his characters’ misfortunes—in this case, death—is only part of what makes him a genius comedian. The film also has the added pleasure of a pitch-perfect romantic comedy. His earlier films, even his most prized Lost in America (1985), have been criticized in some circles for their perceived bleak worldview. In that film, Brooks plays an advertising executive who quits his job and drops out of society with his wife, played by Julie Haggerty. He wants to live the Easy Rider (1969) way: on the road, except in a Winnebago. Their adventure begins in Las Vegas, where the couple plans to renew their vows, but after his wife’s gambling bug bites, their financial “nest egg” is depleted to nothing. Desperate, he becomes a school crossing guard; she becomes a hot dog vendor. Before long, he’s begging for his corporate job back—the implication being that the vanity and financial security sought by the average American is often contrary to our more emotional and largely unattainable desires for freedom.

Brooks’ films so often deal with his depressive characters’ insecurities, nerves, and sense that they’re missing out, and this film puts his protagonist on trial for those traits. That he finds humor in his characters’ misfortunes—in this case, death—is only part of what makes him a genius comedian. The film also has the added pleasure of a pitch-perfect romantic comedy. His earlier films, even his most prized Lost in America (1985), have been criticized in some circles for their perceived bleak worldview. In that film, Brooks plays an advertising executive who quits his job and drops out of society with his wife, played by Julie Haggerty. He wants to live the Easy Rider (1969) way: on the road, except in a Winnebago. Their adventure begins in Las Vegas, where the couple plans to renew their vows, but after his wife’s gambling bug bites, their financial “nest egg” is depleted to nothing. Desperate, he becomes a school crossing guard; she becomes a hot dog vendor. Before long, he’s begging for his corporate job back—the implication being that the vanity and financial security sought by the average American is often contrary to our more emotional and largely unattainable desires for freedom.

In a repeated structure, Brooks often becomes the butt of the joke—in his stand-up comedy, early short films, Saturday Night Live sketches, and other films as well. In his first feature, Real Life (1975)—a mockumentary and send-up of An American Family (1973), the famous PBS series that shows how reality is distorted when a camera is present—he plays an obsessive documentarian whose artistic hubris manufactures reality and betrays his own intentions. His second film, Modern Romance (1981), follows Brooks as he vacillates out of self-doubt and jealousy about whether to commit to his long-standing relationship, fearing that there might be someone else better for him out there. His self-involved characters continued with Mother (1996), a tender story about a novelist whose intense introspection prevents him from seeing that he’s just like his mother, and perhaps that’s why he resents her. In The Muse (1999), his screenwriter character is an unfiltered Hollywood ego, a man who cannot stand to see anyone except himself succeed. And at the end of Brooks’ Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World (2005), he plays a version of himself that might be responsible for the tensions between Pakistan and India.

The very concept of Defending Your Life is pure Brooks. With another one of those great Brooksian lines, Daniel attracts a woman in what must be the unlikeliest of places to meet someone. At a Judgment City comedy club called The Bomb Shelter, the old-school stand-up comedian (Roger Behr) asks Daniel how he died. “On stage, like you,” he replies. In a room of largely senior citizens, Julia laughs and approaches Daniel. She’s sincere and delightful, and, played by Meryl Streep, she’s instantly lovable. The moment also doubles as an homage to Brooks’ father, Harry Einstein (known professionally as Harry Parke), whose passing inspired the film—he died onstage in 1958 during a roast of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. So, besides Daniel’s line—“On stage, like you”—alluding to Brooks’ father, there’s also the moment when Julia and Daniel remark about the awful comedian, and Daniel quips that the stand-up is his father. It’s a joke at the moment, but it has a double meaning for Brooks. The comedian isn’t Daniel’s father, of course, yet the extratextual association makes the moment quietly affecting for what it reveals about the film’s inspiration.

The two of them walk and talk, and in a few brief scenes, Brooks makes us believe that Daniel and Julia fall effortlessly and instantaneously in love, just as they used to in classic Hollywood movies. Julia’s judgment case is far less concerning than Daniel’s; she led an extraordinary life of bravery and honesty, and so they’re looking at fewer days. Such people get better treatment in Judgment City, Daniel discovers, as he walks Julia to her room at The Majestic Hotel (the afterlife’s Four Seasons), which boasts cream-filled chocolate swans and a Jacuzzi tub in her room. What’s more, her prosecutor considers it a privilege to watch scenes from her life; for Lena Foster, it’s certainly much more of a chore to watch clips of Daniel. But whenever Daniel asks someone in charge about the preferential treatment, he’s pooh-poohed or altogether ignored. And when he asks for an explanation, he’s told, “You wouldn’t understand. I don’t mean that as an insult. I mean it literally.” It’s one of the downfalls of being a littlebrain.

Daniel’s trial includes humiliating moments where he self-sabotages out of fear or behaves like a cowardly schlub. He’s forced to sit in a chair and watch moments from his life, and afterward, the attorneys make their arguments on the merits or shortcomings of that particular moment. Daniel can make remarks too, but he relies on Bob Diamond for instruction. Since he didn’t live an especially dignified life, Daniel sits through the regretful procession of moments with a miserable, embarrassed look on his face. In one sequence, he practices a job interview with his wife and plays out demanding a $65,000 salary for himself; when the actual job interview arrives, he accepts the first offer of $49,000 because he’s afraid the interviewer will rebuff the offer. It’s painfully relatable. When Bob Diamond shows a sequence where Daniel broke his leg in a snowmobiling accident and crawled several miles to safety, Lena Foster debunks it, citing that a survival instinct is not bravery. Daniel cannot win. She also critiques him for passing on an opportunity to invest in Casio before they went public (he puts his money into a comparatively risk-free bet: cattle). To summarize her arguments, Lena shows a misjudgment montage that paints him as a buffoon—half of the moments are fear-based, half are just stupid. Daniel has led a life of cowardice and safety; he’s not a bad guy, just neurotic and afraid to fail, easily flattered, and overly concerned with “normal.” When Bob Diamond asks Daniel, “Did you give a lot to charity?” Daniel asks him what he means by “a lot.”

Daniel’s trial includes humiliating moments where he self-sabotages out of fear or behaves like a cowardly schlub. He’s forced to sit in a chair and watch moments from his life, and afterward, the attorneys make their arguments on the merits or shortcomings of that particular moment. Daniel can make remarks too, but he relies on Bob Diamond for instruction. Since he didn’t live an especially dignified life, Daniel sits through the regretful procession of moments with a miserable, embarrassed look on his face. In one sequence, he practices a job interview with his wife and plays out demanding a $65,000 salary for himself; when the actual job interview arrives, he accepts the first offer of $49,000 because he’s afraid the interviewer will rebuff the offer. It’s painfully relatable. When Bob Diamond shows a sequence where Daniel broke his leg in a snowmobiling accident and crawled several miles to safety, Lena Foster debunks it, citing that a survival instinct is not bravery. Daniel cannot win. She also critiques him for passing on an opportunity to invest in Casio before they went public (he puts his money into a comparatively risk-free bet: cattle). To summarize her arguments, Lena shows a misjudgment montage that paints him as a buffoon—half of the moments are fear-based, half are just stupid. Daniel has led a life of cowardice and safety; he’s not a bad guy, just neurotic and afraid to fail, easily flattered, and overly concerned with “normal.” When Bob Diamond asks Daniel, “Did you give a lot to charity?” Daniel asks him what he means by “a lot.”

That his character still feels redeemable is a testament to Brooks’ screen presence and general affability. In a sequence where he and Julia visit an Italian restaurant (all you can eat, of course), Julia embraces the concept, fearlessly slurping endlessly long pasta noodles and giggling throughout. Daniel, spotting Lena Foster at a nearby table, worries that he’s being judged for Julia’s free-spiritedness. His embarrassment and fear of being judged in life have carried over to the afterlife to such a degree that when Julia invites him up to her room, he doesn’t go—he’s afraid the sex might be bad and ruin their effortless love. He’s afraid of consequences, and ultimately, he’s afraid to be happy and take chances. Of Streep, not much is required compared to her other, loftier roles—chameleon-like accents and physical transformations—except that she portrays a lighthearted and sweetly charming woman, which she can do without straining her acting muscles. That Streep disappears into an ordinary person after playing so many extraordinary people is a testament to her talent. It takes a unique screen presence to convey a woman who, just by looking at her, appears spirited, intelligent, passionate, and a sponge of life.

The ending may be predictable, but it’s no less romantic or heartwarming. Judgment has been passed. Julia will move on to the next level of existence. Daniel will not, the smoking gun in his case being when he turned down Julia out of fear. Once again, Daniel’s apprehensions have held him back from what he wants. Defeated, he’s directed to walk on the yellow line to a group of buses that will take some people back to Earth to try again, while others are sent onward to wherever people go after Earth. All at once, Daniel hears Julia calling out his name. She’s a few buses down. When he sees her, he begins banging on the glass and unfastening his seatbelt. He escapes the bus and chases after her, but the doors to her transport are locked. Back in Judgment City, Daniel’s judges, Lena Foster, and Bob Diamond, all watch with admiration. Daniel has grown so much that he will defy the afterlife’s rules—he will avoid walking on the safe and prescribed path—for love. The doors to Julia’s bus open, and the two are reunited in a blissful embrace, traveling together into whatever kind of life they will live next. They might end up being space amoebas or something else beyond our imagination, but at least they’ll be together.

Like most of Brooks’ films, Defending Your Life was well-received upon its release in 1991, but its lightness seemed to bounce off many critics, leaving the film to be not fully appreciated until years later. It doesn’t reveal itself on the first viewing. It’s the kind of film you find yourself returning to again and again, growing as you grow older and your thoughts naturally gravitate toward your mortality. Moreover, Brooks’ unassuming vision is easy to overlook because of its stated familiarity. But he conceives the film’s world as thoroughly as he does his vision of the future in his debut novel, 2030: The Real Story of What Happens to America, published in 2011—a science-fiction dystopia to rival the genre’s greats. Defending Your Life, too, is an inspired idea that’s marvelously executed. And the film’s ability to disarm its weight with humor brings us back. It is somehow downbeat and light, never oppressive. Many have compared his persona to Woody Allen, as both Allen and Brooks share intelligence, neuroses, and self-deprecating styles of humor. But Brooks’ detached sardonic wit doesn’t emanate from the same place as Allen’s New Yorker persona, which is to say, the Los Angeles-based Brooks does not define himself by his Jewishness or through pseudointellectual or psychoanalytic terms. What makes Brooks superior is the miraculous way his characters redeem themselves with the audience, despite their sometimes awful, selfish, or cowardly behavior. He doesn’t romanticize himself, which is not true of Allen’s characters.

Like most of Brooks’ films, Defending Your Life was well-received upon its release in 1991, but its lightness seemed to bounce off many critics, leaving the film to be not fully appreciated until years later. It doesn’t reveal itself on the first viewing. It’s the kind of film you find yourself returning to again and again, growing as you grow older and your thoughts naturally gravitate toward your mortality. Moreover, Brooks’ unassuming vision is easy to overlook because of its stated familiarity. But he conceives the film’s world as thoroughly as he does his vision of the future in his debut novel, 2030: The Real Story of What Happens to America, published in 2011—a science-fiction dystopia to rival the genre’s greats. Defending Your Life, too, is an inspired idea that’s marvelously executed. And the film’s ability to disarm its weight with humor brings us back. It is somehow downbeat and light, never oppressive. Many have compared his persona to Woody Allen, as both Allen and Brooks share intelligence, neuroses, and self-deprecating styles of humor. But Brooks’ detached sardonic wit doesn’t emanate from the same place as Allen’s New Yorker persona, which is to say, the Los Angeles-based Brooks does not define himself by his Jewishness or through pseudointellectual or psychoanalytic terms. What makes Brooks superior is the miraculous way his characters redeem themselves with the audience, despite their sometimes awful, selfish, or cowardly behavior. He doesn’t romanticize himself, which is not true of Allen’s characters.

Only Defending Your Life offers a genuine romantic conclusion that deviates from Brooks’ usual punchline endings, which often find his characters in comic misfortune—a prototype version of how Larry David usually receives some comeuppance in episodes of HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm. Whether it’s Brooks pathetically begging for his old job back after quitting in Lost in America or realizing Sharon Stone’s titular character isn’t done with him yet in The Muse, Brooks’ characters rarely grow and often find themselves stuck, hilariously so. In Defending Your Life, his climactic decision to deviate from the path, unafraid, proves uncommon and endearing, complete with a romantic swell that is unique in his body of work—and blithely accented by Michael Gore’s music. The finale also contains a genuine lesson. Brooks told Film Comment’s Robert DiMatteo, “If you can figure things out, so that you don’t walk around feeling like some insecure jerk all day, then maybe you won’t treat people that way.” The rarity of a feel-good ending combined with a philosophical perspective in a Hollywood romantic comedy cannot be overstated.

There are many superlatives and hyperbolic statements in this appreciation of Brooks’ film, but it’s just that kind of comedy. It makes you smile endlessly and warms your heart. And its humor is pleasant, PG-rated, yet filled with a subtle wit that, more than any other Brooks film, ends in pure optimism. Of course, the old myth that humans only use a small percentage of their brain has since been debunked and, in a way, invalidates the entire concept of Defending Your Life. But no matter. Such scientific reality has no place in a comic fantasy like this; the film plays by its own well-established rules, which can lead one into a speculative How would I be judged? inner debate. This is the film’s most enduring quality and what invites us back, again and again, to remind us that fear serves to limit and demarcate the boundaries of our lives. Beyond the romance at the film’s center, losing yourself in the discovery of Judgment City and how it operates are among the most joyful components of Brooks’ film. He makes the afterlife seem safe, unthreatening, and familiar, and in turn, he removes many of our apprehensions about the often frightening notions of death. Above all, his assessment of existence as fear management on an existential and spiritual scale simplifies life and serves as an achievable ideal. Consider your own life under this lens, and you might start living it differently. How many films can do that?

Bibliography:

Aster, Ari. “Defending Your Life: Real Afterlife.” Criterion.com. 31 March 2021. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7338-defending-your-life-real-afterlife. Accessed 2 April 2021.

Bowman, Donna. “Looking Through the Veil: The Theology of Movie Afterlives.” Criterion.com, 19 April 2021. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7360-looking-through-the-veil-the-theology-of-movie-afterlives. Accessed 20 April 2021.

Brooks, Albert, and Gavin Smith. “All the Choices: Albert Brooks Interviewed by Gavin Smith.” Film Comment, vol. 35, no. 4, 1999, pp. 14–21.

Brooks, Albert, and Robert DiMatteo. “Real Afterlife.” Film Comment, vol. 27, no. 2, 1991, pp. 18–24.

Green, Daniel. “‘We’re Getting a False Reality Here’: Albert Brooks and the Comic Idea.” Film Criticism, vol. 17, no. 1, 1992, pp. 26–37.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review