The Definitives

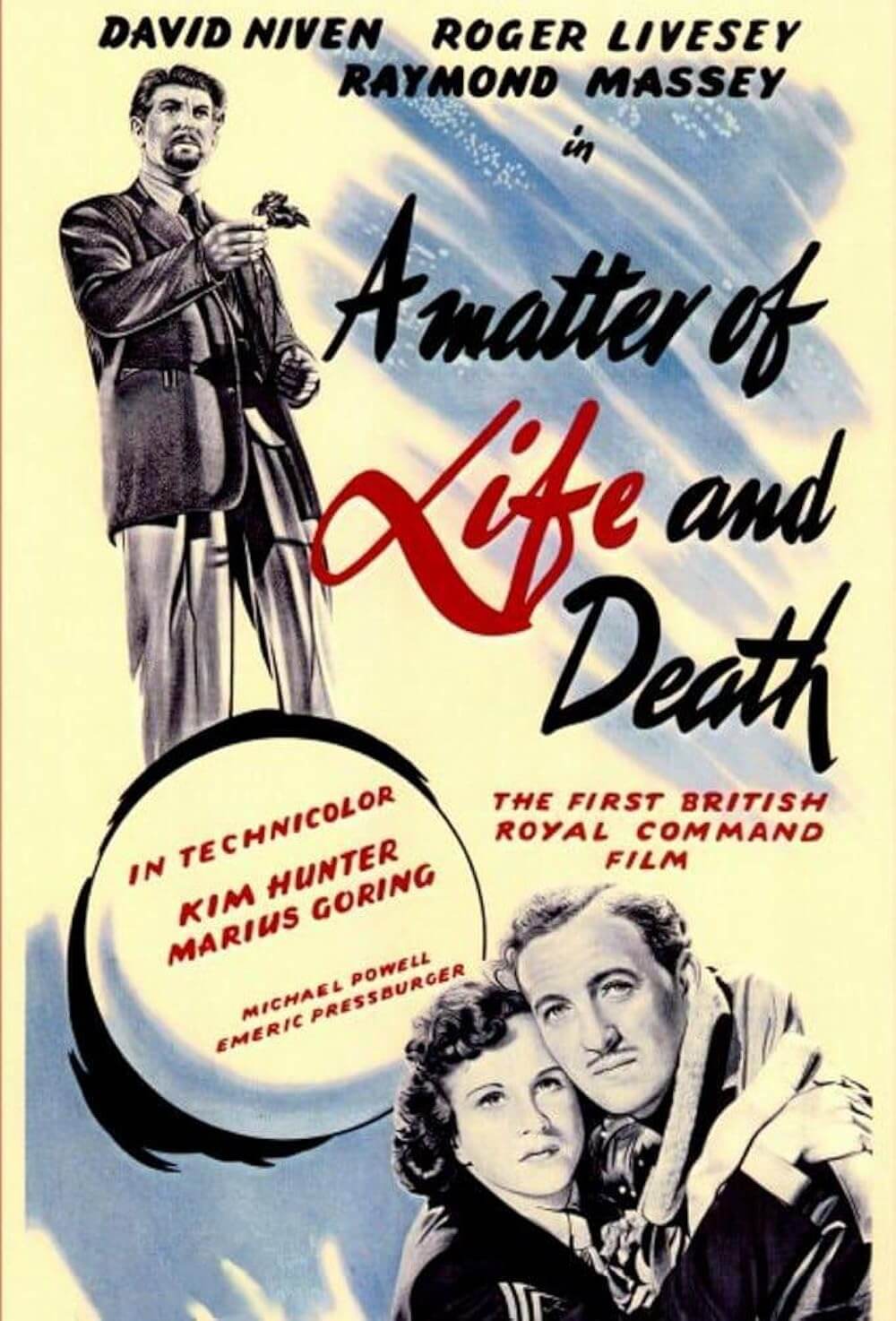

A Matter of Life and Death

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death opens by touring the vast emptiness that surrounds our little planet. Constellations twinkle and massive formations of burning gasses glow in the impossible distance. “This is the universe,” says an omnipotent narrator. “Big, isn’t it?” The frame continues to journey through the cosmos, identifying a pageant of interstellar wonders until it settles upon Earth, a small but reassuring orb dwarfed by the limitless space that surrounds it. In these endless reaches of the cold, indifferent universe, the only certainty of meaning we have is the love we feel, and Powell and Pressburger spin a fantastical yarn about love’s infinite expanse. Down on Earth, World War II rages, and a flier for the British Royal Air Force is going down. The conductors in Heaven have readied themselves to gather him up for eternity. And by some miracle, the flier does not die, though he was supposed to; instead, he falls in love with an American woman. But Heaven’s bookkeepers want their due, and to defend his life, the flier must go on trial in the clouds to argue his case that love conquers all. Through the course of this story, everything can be put on hold—our ping pong matches, our picnics, our petty squabbles over imaginary lines drawn in the sand, and every flickering star in the expansive universe—by something as simple, but of course not simple at all, as love.

The film exists in two worlds, a colorful Earthly plane shot in beautiful three-strip Technicolor, and a heavenly Other World of monochrome; as the opening titles explain: “one [world] we know, and another world which exists only in the mind of a young airman whose life and imagination have been violently shaped by war.” Indeed, the word “Heaven” is never used; it is referred to only as the Other World, and according to the opening titles “any resemblance to any other world known or unknown is purely coincidental.” When the film was released in 1946, Powell and Pressburger’s home of Great Britain had been shaped by war too, and their film responded to that by attempting to solidify failing Anglo-American ties. Known as their company name The Archers, Powell and Pressburger directed, wrote, and produced as a team. But more than a piece of postwar propaganda, their film remains a triumph of visual design and conceptual narrative complexity, shot in alternating sequences of rich colors and black-and-white by the Archers’ frequent cinematographer Jack Cardiff. And though British cinema was predominantly realist in nature, few films by the Archers are more intimately fantastical than A Matter of Life and Death. Together, Powell and Pressburger would later explore fantasy spilling into reality with The Red Shoes (1948) and The Tales of Hoffman (1951), but this film would become their most daring work upon its release in terms of its lasting and dramatic impact on international audiences.

While descending in a damaged airplane, Peter (David Niven), a British poet-turned-airman, radios that he’s going down, and during his transmission, he falls in love with June (Kim Hunter), the American Women’s Army Corps voice taking his report on the other end. With no parachute and convinced he’s leaping to his demise, Peter bails out before his certain-death crash and comes to on a beach. He believes he’s arrived in Heaven, but soon he discovers that he did not die and rushes to find June, and they fall madly in love. Meanwhile, Heaven’s bureaucrats argue that Peter should have died. When he leaped from the plane into a thick English fog, he was lost by his heaven-sent Conductor 71, a Frenchman (Marius Goring) from revolution days. Obsessed with love, the Frenchman approaches Peter and reluctantly tells him that he must return to Heaven, but Peter argues that he must be allowed to stay on Earth, given his newfound romance with June and the authority thereof. Heaven agrees to consider Peter’s pleas in an official hearing where he will defend himself against prejudiced Bostonian prosecutor, Abraham Farlan (Raymond Massey), the first American man shot by British soldiers in the Revolutionary War. At the same time, June believes Peter’s encounter with Heaven’s satrap is a hallucination; she introduces Peter to Dr. Reeves (Roger Livesey), who plans to operate on Peter and correct damage leftover from a 3-year-old concussion. The film alternates between Heaven and Earth as Peter attempts to prepare his defense. And Peter finds the ideal defender when Reeves suddenly dies, and then agrees to serve as his advocate in Heaven’s court. On Earth, doctors prepare Peter for brain surgery to cure his hallucinations; in Heaven, Reeves uses a single tear from June, preserved on a rose, as evidence of her love. But only when the heavenly court asks June to take Peter’s place, and she willingly agrees, does Peter win his case. Just then, Peter’s doctors complete his operation, and later he awakens with June by his side, free of his condition.

While descending in a damaged airplane, Peter (David Niven), a British poet-turned-airman, radios that he’s going down, and during his transmission, he falls in love with June (Kim Hunter), the American Women’s Army Corps voice taking his report on the other end. With no parachute and convinced he’s leaping to his demise, Peter bails out before his certain-death crash and comes to on a beach. He believes he’s arrived in Heaven, but soon he discovers that he did not die and rushes to find June, and they fall madly in love. Meanwhile, Heaven’s bureaucrats argue that Peter should have died. When he leaped from the plane into a thick English fog, he was lost by his heaven-sent Conductor 71, a Frenchman (Marius Goring) from revolution days. Obsessed with love, the Frenchman approaches Peter and reluctantly tells him that he must return to Heaven, but Peter argues that he must be allowed to stay on Earth, given his newfound romance with June and the authority thereof. Heaven agrees to consider Peter’s pleas in an official hearing where he will defend himself against prejudiced Bostonian prosecutor, Abraham Farlan (Raymond Massey), the first American man shot by British soldiers in the Revolutionary War. At the same time, June believes Peter’s encounter with Heaven’s satrap is a hallucination; she introduces Peter to Dr. Reeves (Roger Livesey), who plans to operate on Peter and correct damage leftover from a 3-year-old concussion. The film alternates between Heaven and Earth as Peter attempts to prepare his defense. And Peter finds the ideal defender when Reeves suddenly dies, and then agrees to serve as his advocate in Heaven’s court. On Earth, doctors prepare Peter for brain surgery to cure his hallucinations; in Heaven, Reeves uses a single tear from June, preserved on a rose, as evidence of her love. But only when the heavenly court asks June to take Peter’s place, and she willingly agrees, does Peter win his case. Just then, Peter’s doctors complete his operation, and later he awakens with June by his side, free of his condition.

Two possibilities can be construed from A Matter of Life and Death: 1) Heaven exists, and Reeves’ defense of Peter in Heaven’s court was a success, or 2) Heaven “exists only in the mind,” and Peter’s brain injury forced his psyche to create an elaborate fantasy to cope with his surviving an impossible state of affairs. Consider that Heaven exists, with its plastic-wrapped angels’ wings and Coke machine for newly arriving soldiers. Suddenly the film becomes an ostentatious fantasy on par with Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941), steeped in other-worldly associations. When Peter awakens on the beach, he sees a Pan figure in the form of a naked boy playing a flute to his goats. Is this a boy, or is it Pan himself? And his first encounter with Conductor 71 becomes an insight into the vast powers of Heaven when the Frenchman pauses the universe and explains, “We are in space, not in time.” A disbeliever, Peter responds, “Are you cracked?” But if Heaven is for real, then Powell and Pressburger have created a curious bureaucracy. Alfred Junge’s set designs have an almost fascistic embrace of the classical and monumental to them, as though the totalitarian state of Heaven has been overrun by order, bookkeeping, and regimentation. In one breathtaking shot, realized with a matte painting, heavenly officials look down at a record hall, and the ceiling’s circular openings shine glowing light below—an imposing if intimidating image to be sure. Associations to the persistent administrative quality of the Nazi party, complete with flat, gray, monumental architecture, would not have been lost on then-modern viewers.

Another reading, perhaps the one that has more onscreen scientific evidence in its favor, is that Heaven does not exist, and Peter’s visions are as the opening title explains, “in the mind of a young airman whose life and imagination have been violently shaped by war.” When he first falls into the ocean after his plane goes down, the shot fades out with Peter in the water. Does he dream of Heaven, which in turn becomes a coping mechanism through which hallucinations play out his internal, neurological struggle? If this is true, then the crash was merely a catalyst for an existing condition—in fact, Peter admits to having had headaches six months prior to the crash from a years-old concussion. As Reeves points out, Peter’s neurological damage is evidenced in the phantom smell of fried onions. Unless fried onions are the scent of Heaven (and they very well may be), such an olfactory hallucination as phantosmia is a documented sign of neurological and psychological disorders. In this possibility, Peter’s status as a poet allows him to create a detailed fantasy for himself to work his way through the trauma of a near-death experience, compounded by whatever vague malady had invaded his brain years before. Had Peter not been an intelligent, imaginative man, he may not have dreamed himself into this predicament; as one character observes, “Stupidity has stopped many a man from going mad.” This scenario aligns with a prevalent theme in Powell and Pressburger’s work, where the artist’s own talent drives them mad—an idea most pronounced in The Red Shoes, which follows a ballet dancer whose artistic passion convinces her that her ballet shoes have taken control, and they soon send her leaping to her death in an act of life imitating art.

Just as two main but polarized readings can be drawn from A Matter of Life and Death, Powell and Pressburger’s use of color has two equally polarized potential meanings. The Archers use color to differentiate the opposing worlds of Earth and Heaven, and how one interprets the meaning of color itself can inform the readings of the film. Technicolor or monochrome represent either reality or fantasy; color can be interpreted as a symbol of realism or the ethereal, but its significance remains subjective for the film’s audience. The alternating Technicolor and monochrome presentation offers a fascinating problem for the viewer, who must assign meaning to the nature of color itself in order to further justify which reading they accept, that Heaven is real or imagined. If Heaven exists, then it’s curious that the Archers chose to depict it in black-and-white, an unnatural and expressive form of representation. Then again, some moviegoers would classify black-and-white images as even more real than color cinema; in photography, black-and-white is often associated with documentary realism. In a modern cinematic sense, black-and-white correlates to so-called classic films before color stock was the standard, while today’s films that are painstakingly shot in black-and-white denote their arthouse intent. But if we are to interpret reality for how it exists in a natural state, then reality is in color, and therefore reality inhabits the earthbound scenes, whereas Heaven is a fantasy, and fantasies are rarely accompanied by a black-and-white presentation by design. Alas, Powell and Pressburger have never confirmed which world they intended to be real and which was fantastical, and that ambiguity has sustained the film’s reputation since its release.

What could be more heroic, masculine, and romantic than a noble soldier accepting death through an act of fatalistic acceptance, only to miraculously survive, and then fight off Heaven to protect his newfound love? These qualities would come to represent two major subtexts working in the film: 1) a thread of propagandistic nationalism in the hero’s survival and bravery in the face of death; 2) a national identity established by a pointedly British individual and his preservation of the home, meaning June. In 1945, after the end of World War II, the British postwar reconstruction faced a dramatic decline in the USA’s economic support. The status of the British Empire as a global power, despite its prevalent role in Allied efforts, had been diminished by a broken economy and demoralized by postwar rationing, their dependence on American money, and the departure of India from the Empire. As a reaction, the UK government imposed a tax on all imported films, and Hollywood responded by placing an embargo on exports. These deficiencies not only injured the British national identity but meant fewer films in England’s cinemas. And while industry leaders eventually renegotiated and repealed the taxes and restored American films to British cinemas, the interim allowed a brief but glowing emergence of a British National Cinema. In such a climate, propaganda was natural, if not necessary to reestablish a sense of national pride. The standard mode of wartime propaganda found heroic, masculine, duty-bound men battling against Nazis or Japanese soldiers, and if they made it through the war, they arrived at home where their women waited.

But Powell and Pressburger had already deviated from the typical wartime propaganda scenario for The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), which proposed an ideological shift in attitude from dutiful, time-honored traditions to a more humanist stance on World War II. Similarly, A Matter of Life and Death uses Peter as a symbolic figure for all of the British Empire and, through his very British attributes and the character’s questioning of his place in the universe, calls into question the state of the British Empire’s national identity such as it was in 1945. Through the course of the film, any discussion of winning the war remains nonexistent to Peter; moreover, he even rebels and becomes resistant to both Heaven and military authorities, all to preserve his home—his love for June. Because this represents such a dramatic change in his ideology, he’s forced to psychologically, and perhaps unconsciously, consider his decision by way of the film’s events: his court case in Heaven, or his having to overcome his condition via surgery. In its hallucinatory elements, A Matter of Life and Death recalls The Wizard of Oz (1939), since Peter’s vision of Heaven could be real or imagined, all part of some brain ailment. However, the film has more in common with It’s a Wonderful Life (1946): both films begin with an overview of the stars and feature a heavenly emissary; both sweep the protagonist away into an existential What if? question; both contain a storyline that has a curative property for the character, through which the protagonist’s existential uncertainties are resolved. And yet, Powell and Pressburger take what, on the surface, appears to be a character’s struggle with his inner demons, and use his ultimate self-identification to elucidate what it means to be British, and further, cement England’s standing in the postwar world.

A Matter of Life and Death is saturated in an unmistakable British identity, from its “ridiculous English climate,” to its Shakespearian references throughout, to a sound byte from Winston Churchill in the opening. Peter announces his own Britishness, and thus the film’s, by quoting Sir Walter Raleigh in his broadcast as his plane descends to Earth in the opening frames: “‘Give me my scallop-shell of quiet, My staff of faith to walk upon, My scrip of joy, immortal diet, My bottle of salvation, My gown of glory, hope’s true gage, And thus I’ll take my pilgrimage.’ …I’d rather have written that than flown through Hitler’s legs!” And when he leaps from his plane, he’s lost in a “pea-souper” English fog—that such a fog could outwit Heaven’s conductor is a hilarious in-joke for Powell and Pressburger and British audiences. Elsewhere, jabs at the USA by way of Farlan’s loud Americanism serve the same purpose when he announces America as “the only place where a man is full-grown.” But perhaps most significant in this theme is the Archers’ use of Shakespeare. With Peter recovering in a military hospital, nearby a group of soldiers rehearse a scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. How appropriate, since Shakespeare’s play considered many of the same themes and presented a fantasy world that may or may not be real. As the rehearsal goes on, one actor shouts “Bottom’s not a gangster!” and references the 1935 film version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream starring James Cagney, Hollywood’s go-to gangster, as Bottom. Such a momentary allusion is very British but also very internationalist, as Powell and Pressburger routinely instill their loyalty to English culture but also acknowledge the art of other cultures. That Reeves and Farlan eventually find a common ground in the film’s love conquers all resolution (just as Peter and June, an Englishman and an American, end up together) speaks to the propagandistic intent of the film.

A Matter of Life and Death is saturated in an unmistakable British identity, from its “ridiculous English climate,” to its Shakespearian references throughout, to a sound byte from Winston Churchill in the opening. Peter announces his own Britishness, and thus the film’s, by quoting Sir Walter Raleigh in his broadcast as his plane descends to Earth in the opening frames: “‘Give me my scallop-shell of quiet, My staff of faith to walk upon, My scrip of joy, immortal diet, My bottle of salvation, My gown of glory, hope’s true gage, And thus I’ll take my pilgrimage.’ …I’d rather have written that than flown through Hitler’s legs!” And when he leaps from his plane, he’s lost in a “pea-souper” English fog—that such a fog could outwit Heaven’s conductor is a hilarious in-joke for Powell and Pressburger and British audiences. Elsewhere, jabs at the USA by way of Farlan’s loud Americanism serve the same purpose when he announces America as “the only place where a man is full-grown.” But perhaps most significant in this theme is the Archers’ use of Shakespeare. With Peter recovering in a military hospital, nearby a group of soldiers rehearse a scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. How appropriate, since Shakespeare’s play considered many of the same themes and presented a fantasy world that may or may not be real. As the rehearsal goes on, one actor shouts “Bottom’s not a gangster!” and references the 1935 film version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream starring James Cagney, Hollywood’s go-to gangster, as Bottom. Such a momentary allusion is very British but also very internationalist, as Powell and Pressburger routinely instill their loyalty to English culture but also acknowledge the art of other cultures. That Reeves and Farlan eventually find a common ground in the film’s love conquers all resolution (just as Peter and June, an Englishman and an American, end up together) speaks to the propagandistic intent of the film.

By some coincidence, production began on August 14, 1945—the same day Japan surrendered to General MacArthur and therein ended the Pacific campaign. Powell and Pressburger originally conceived A Matter of Life and Death earlier in the war, in 1944, in an effort to strengthen relations between England and America. They were inspired by an actual account of an RAF pilot who leaped from a burning plane and survived with only minor injuries. Head of the Ministry of Information’s film department, Jack Beddington asked Powell to address worsening Anglo-American relations in “a big film,” and J. Arthur Rank, who ostensibly controlled the British film industry, approved the production through his General Film Distributors label as a response to an increased public interest in British-centric films. Disdain had grown in Britain for American servicemen, as well as Britain’s economic dependence on American money, and only Powell and Pressburger could address such issues without them seeming like an overt propaganda piece. Over the lengthy pre-production process, the filmmakers were forced to wait for months before the British Ministry made Technicolor film stock available, as it had been reserved for aerial combat training footage. But the monochrome pieces were just as complicated to film, requiring dozens of sketches to prepare the elaborate Other World locations and architectural designs. Detailed scale models helped prepare what would become an eighty-five-ton escalator set, complete with towering sculptures and 266 steps. Designing the elaborate sets was the aforementioned German production designer Alfred Junge, who had worked with Alexander Korda and Alfred Hitchcock before, and first teamed with the Archers on Contraband (1940) as a set designer. Junge also contributed his considerable vision to The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and A Canterbury Tale (1944), among others, but his work on A Matter of Life and Death was his most fantastical.

Powell and Pressburger continued to experiment with their medium to a surprising degree for a film containing such an important international message. Shots from Reeve’s camera obscura, startling freeze frames, a shot from Peter’s eyelid closing as he goes under for surgery, the lack of sound in one sequence, and reversed footage all show the Archers exploring the limits of the viewer’s aural and visual experience. But no effect was more impressive than the film’s use of color, and lack thereof—the French conductor observes about Heaven, “one is starved for Technicolor up there.” Cinematographer Jack Cardiff, then a Technicolor expert who had not yet shot an entire picture on his own, but filmed second unit material for The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, was hired by Powell. As a novice camera operator, Cardiff had trained at Technicolor’s first London branch in 1935 and quickly became a specialist who was willing to test the expensive medium’s limits, much to the chagrin of Technicolor’s progenitors Herbert and Natalie Kalmus. A Matter of Life and Death presented a unique set of challenges given how it frequently fades in an out of color fantasy sequences, requiring Cardiff to under-develop scenes on color stock to achieve a pearly monochrome effect (as in “pearly gates” the crew was quick to point out). This is highlighted in a wonderful sequence when the black-and-white Peter rushes down the stairway back to his body and consciousness to recover his color. Cardiff would later earn an Oscar for his work on Black Narcissus (1946), but his expressive work on A Matter of Life and Death burns brightly in the opening scene’s fiery cockpit or a garden scene that shows an array of red and magenta flowers—a moment that’s so gorgeous and diverse in its blooms that it could be accused, flatteringly, of Technicolor self-indulgence.

When the finished film was screened on November 1, 1946, at a Royal Command Film Performance, it had been chosen over a variety of both American and British films, and the screening would be attended by the King, Queen, various royalty, the Prime Minister, and a wide range of stars including Michael Redgrave, Margaret Lockwood, and Ray Milland. While the event was a success, not all reviewers, specifically from British reviewers, appreciated the perceived anti-British undertones Powell and Pressburger had injected into their film. British critics such as E.W. and M.M. Robson, who had famously degraded the Archers in their 1944 pamphlet The Shame and Disgrace of Colonel Blimp, believed A Matter of Life and Death meant to “bash the British in the sight of our Allies” to strengthen foreign relations. A critic in The Observer noted that the film “leaves us in grave doubts whether it is intended to be serious or gay.” Some, specifically a Soviet critic writing in 1946, attacked its message in the postwar climate and mistakenly interpreted Heaven as an assault against a Soviet utopia of order and bureaucracy from which Peter is desperate to escape. Worse, the notion of a bonded USA and Great Britain through the course of the film implied, for the Soviet critic anyway, an underhanded and conspiratorial union at work. Though it’s not impossible to understand where such a reading could derive, the Archers were more interested in experimenting with forms of narrative and visual meaning, and moreover improving Anglo-American relations. Other critics such as News Chronicle‘s Richard Winnington argued that British film itself was characteristically rooted in a realism that is the “true business of the British movie,” and therefore the Archers’ film was anything but British. However, overseas in the USA, where the film was retitled Stairway to Heaven to appease distributors who were convinced audiences didn’t want to see “death” in a film title, American critics celebrated it. Bosley Crowther’s article in the New York Times defended the film, writing “literally is not the way to take this deliciously sophisticated frolic in imagination’s realm. For this is a fluid contemplation of a man’s odd experiences in two worlds…it’s a delight.”

When the finished film was screened on November 1, 1946, at a Royal Command Film Performance, it had been chosen over a variety of both American and British films, and the screening would be attended by the King, Queen, various royalty, the Prime Minister, and a wide range of stars including Michael Redgrave, Margaret Lockwood, and Ray Milland. While the event was a success, not all reviewers, specifically from British reviewers, appreciated the perceived anti-British undertones Powell and Pressburger had injected into their film. British critics such as E.W. and M.M. Robson, who had famously degraded the Archers in their 1944 pamphlet The Shame and Disgrace of Colonel Blimp, believed A Matter of Life and Death meant to “bash the British in the sight of our Allies” to strengthen foreign relations. A critic in The Observer noted that the film “leaves us in grave doubts whether it is intended to be serious or gay.” Some, specifically a Soviet critic writing in 1946, attacked its message in the postwar climate and mistakenly interpreted Heaven as an assault against a Soviet utopia of order and bureaucracy from which Peter is desperate to escape. Worse, the notion of a bonded USA and Great Britain through the course of the film implied, for the Soviet critic anyway, an underhanded and conspiratorial union at work. Though it’s not impossible to understand where such a reading could derive, the Archers were more interested in experimenting with forms of narrative and visual meaning, and moreover improving Anglo-American relations. Other critics such as News Chronicle‘s Richard Winnington argued that British film itself was characteristically rooted in a realism that is the “true business of the British movie,” and therefore the Archers’ film was anything but British. However, overseas in the USA, where the film was retitled Stairway to Heaven to appease distributors who were convinced audiences didn’t want to see “death” in a film title, American critics celebrated it. Bosley Crowther’s article in the New York Times defended the film, writing “literally is not the way to take this deliciously sophisticated frolic in imagination’s realm. For this is a fluid contemplation of a man’s odd experiences in two worlds…it’s a delight.”

Over time, critics and film scholars have revisited the picture and ranked it not only among the Archers’ finest but among the finest British pictures ever made. Powell and Pressburger leave any answers beyond a cheery ending, where Peter and June live happily ever after, up to the subjective viewer. When A Matter of Life and Death resolves its surface narrative, its audience must determine how and why Peter and June end up together, be it a matter of heavenly intervention or neurological science. By challenging their audience to fill in the details, their film’s politicized intentions to bolster nationalism and strengthen Anglo-American ties become less important than the viewer’s own interpretation. Such thematic complexity and trust in the audience is matched only by the film’s technical innovation and how expertly it has been tied into these themes. And like many pictures by the Archers, their timely subject matter has since transcended time and space, reaching further than its intended purpose and gaining in significance since its release, as their films often do. In another sense, by removing its very politicized, very specific postwar intentions toward British National Cinema and the unification of international interests, A Matter of Life and Death becomes an even more profound message. It becomes a question of faith and science, and a loving admiration for how significant two small people are in a hopelessly vast universe.

Bibliography:

Christie, Ian. Arrows of Desire: The Films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Faber & Faber, 1994.

Christie, Ian. Powell, Pressburger and Others. BFI (British Film Institute), 1978.

Christie, Ian and Moor, Andrew, eds. The Cinema of Michael Powell. BFI (British Film Institute), 2005.

Moor, Andrew. Powell and Pressburger: A Cinema of Magic Spaces (Cinema and Society). I.B. Tauris; Distributed in the U.S. by Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Powell, Michael. A Life In Movies: An Autobiography. Heinemann, 1986.

Powell, Michael. Million Dollar Movie. Heinemann, 1992.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review