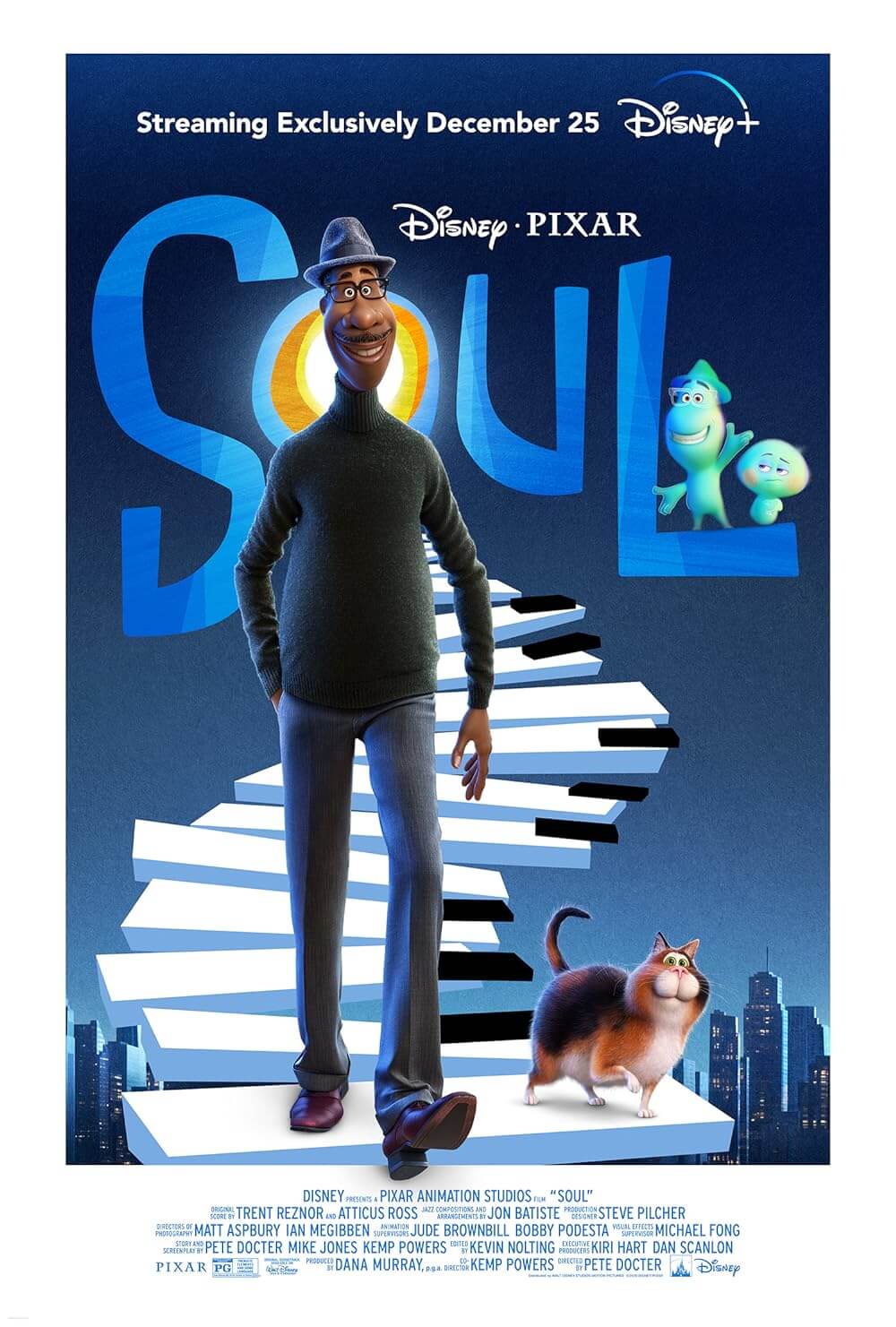

Soul

By Brian Eggert |

Pixar has made a warm-hearted legacy out of anthropomorphizing objects, creatures, and even feelings that we might not otherwise assign personality traits. Whether it’s Andy’s inanimate toys or a trash-compacting robot rummaging in the post-apocalypse, the animation house finds humanity in the unlikeliest of places. Each new story gets to the root of why people think and feel, often confronting subject matters untried in a form narrowly deemed kids’ stuff. Take Pixar’s Soul, their twenty-third feature, in which the protagonist dies before the opening credits. Death isn’t an easy subject, especially with children in the audience (at home during the pandemic, watching the film’s debut on Disney+). Still, once more, Pixar clears boundaries with effortless grace and inspired world-building. Here’s another achingly tender yet digestible breakthrough from director Pete Docter, whose Up (2009) and Inside Out (2015) turned emotionally raw material into life-affirming adventures. Pixar delivers their latest in a long line of intricately conceived worlds, portraying metaphysical planes of existence with visual clarity and propulsive narrative thrust. And yet, despite its grandiose themes that include the meaning of life itself, the film imparts a pearl of wisdom that compares life’s dailiness to an improvisational jazz composition.

The first Pixar film to center on a Black character, Soul follows Joe Gardner (Jamie Foxx), a beleaguered middle school music teacher who narrowly avoids getting hit by cars or crushed by falling construction debris in the first scenes, only to fall to his death down an open manhole unceremoniously. Saddled with midlife disappointments and perceived failures, Joe, at once lanky and soft around the midsection, dreams of becoming a professional jazz musician, despite the protests of his realist mother, Libba (Phylicia Rashad). But during an impromptu audition with a famous jazz saxophonist, Dorothea Williams (Angela Bassett), he lands the opportunity of a lifetime. After years of rejection, disappointment, and mediocrity, Joe’s life finally has meaning. A few moments later, he’s a blue drip riding an escalator to the Great Beyond—imagery reminiscent of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946). Now a semi-transparent soul, Joe resists the white light of eternity, where other souls disappear with a crackle like bugs in a zapper—an unintentionally frightening image—and races in the other direction, announcing, “I’m not dying today, not when my life just started.”

If the concept of teardrop souls on an elevator to a white light seems commonplace, the film’s design comes alive when Joe falls through various planes of existence to the Great Before. It’s a luminous epicenter where universal beings—all named Jerry and voiced by the likes of Alice Braga, Richard Ayoade, Wes Studi, and others—oversee the development of budding souls. Although Pixar’s Coco (2017) explored the afterlife with more cultural specificity and distinction, the worlds of Soul remain beautifully and memorably conceived, if decidedly modernist. The Great Before’s Jerrys look like line-drawings by Pablo Picasso or Joan Miró and, appropriately, move fluidly about their environment. The black-and-white zones between these worlds resemble the geometric planes found in transcendent, inter-dimensional science-fiction, like Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014). As ever, Pixar tackles difficult subjects with vision, allowing the viewer to accept an unavoidable reality by way of a fantastical cinematic world.

Unlike Coco’s origins in Mexican identity, Soul combines a techno-futurist look with Casper the Friendly Ghost’s fluffy pleasantness for a world as unique-yet-familiar as Albert Brooks’ soul weigh-station in Defending Your Life (1992). Even the electronic beep-boop-bop music of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ score builds the cold utopian structure of the in-between realm. In contrast, Jonathan Batiste’s lively jazz compositions accent the land of the living. Like Brooks’ film, there’s an elaborate series of rules and officialdom guiding souls from one existence to the next. New souls must find their “spark” before earning a body on Earth. Joe, looking for a loophole, finds himself in a position to mentor a young soul, No. 22 (Tina Fey), and help her find her spark—which, explained in a sharp montage, he plans to steal for his second chance at life. But 22 is a misfit soul whose previous mentors include Gandhi, Lincoln, and Mother Theresa, all of whom have thrown up their hands in defeat, unable to find 22’s spark, in part because 22 feels “meh” about life experiences.

If the setup sounds vaguely familiar, you’re probably thinking of Inside Out, Docter’s other film that gets to the root of what makes people tick. That film suggested individual emotions, each operating in tandem, often in conflict, inhabit the control room in our brain. Another metaphysical journey into our inner selves, Soul considers just that, our intangible essence or spirit—if you believe in that sort of thing. And while the story about Joe trying to return to his body seems straightforward enough, Docter and his co-writers, playwright Kemp Powers (also co-director) and Mike Jones, complicate matters with a few goofy twists—reminiscent of this year’s other Pixar feature, Onward, in which an elf boy sets out on an adventure, weirdly enough, with his father’s bottom half. Joe and 22 soon return to Earth, but 22 ends up in Joe’s body, and Joe’s soul ends up in a hospital therapy cat, Mr. Mittens. It’s a random and hilarious turn, good for a few laughs, but downright strange next to the film’s comparatively appropriate Carl Jung references. It becomes apparent that Soul is more about appreciating the joy of lowbrow pleasures than achieving high-minded ambitions.

Once Joe and 22 explore Earth, Soul’s animation transitions from the cartoony Great Before to jaw-droppingly photo-real, and it’s a brilliant and intentional transition from simplistic to complicated. Through Joe’s body, 22 experiences the tastes, sounds, and smells of the city—a New York that looks like a convincing, bustling metropolis. It’s the kind of animation that feels revolutionary, the way Pixar wowed audiences back in 2001’s Monsters, Inc. with the intricate details in Sully’s fur. The film comes alive with crowds, natural lighting, closely observed storefronts, and tangible character designs—all evidence that Pixar is capable of realism but makes conscious choices to stylize. Quite intentionally, some of the most impressive visual sequences occur in the most customary of places: the neighborhood barbershop, an atmospheric jazz club, the subway, and Joe’s modest apartment. Joe and 22 race from location to believable location with an urgency that echoes the bustling jazz score. Gradually, the viewer realizes that the Great Beyond cannot compare to the vibrancy of everyday life. That, it turns out, is kind of the point.

Still, though designed to seem less alive than the scenes on Earth, the otherworldly flourishes bear a wonderful kind of minimalism in their simple colors and straightforward designs. Joe discovers a desert-like region of a perpetual deep blue night where lost souls—who appear as depressive, cycloptic blobs—wander until they find their purpose. Those out of sync with their soul’s spark drag their feet in the sand, and just overhead, souls who find themselves in perfect harmony with their spark float in a dream state. When Joe first auditions for Dorothea, he drifts away into this floating euphoria, what’s called “The Zone”—an out-of-body oneness with your passion, whether it’s playing an instrument, writing a book, cutting hair, or making a taco. We’ve all been in The Zone before. And this plane between limbo and The Zone later becomes the setting for a third act extravaganza, as Joe chases 22 through the Great Before with the help of a mystic named Moonwind (Graham Norton), whose meditative states on Earth allow him to traverse the astral plane. Among all of the out-there ideas in Soul, the most confronting comes when Moonwind remarks, “When joy becomes an obsession, one becomes disconnected from life.”

Some viewers may find fault with Soul’s conclusion and how the screenplay allows Joe to settle for less. After everything he goes through to perform in Dorothea’s quartet, the film resolves that one’s dreams and personal ambitions do not define them; rather, people are defined by their ability to appreciate the simple pleasures of everyday life—from the joy of pizza to the pleasure of “the chair” in the barbershop. For those who have lofty expectations from life, it’s hardly an inspirational message. Instead, it feels like a salve to a life bound for disappointment and uncertainty. And yet, the film’s lesson remains healthy and realistic—and I dare say, sophisticated—suggesting that life should not be defined by professional success alone. People regularly must roll with the punches, navigate failure, and subsist through the seemingly mundane. But when people have such singular aspirations (“I would die a happy man if I could perform with Dorthea Williams,” Joe declares early on), they forget that a single experience is not a life. There are a million finer moments in-between major events that should be cherished to the same extent. And a more conventional film would have implied that those experiences have lesser value than the rare dream-come-true.

At its simplest, Pixar’s latest feels like a throwback to soul-inhabiting films such as Heaven Can Wait (1943) or Heart and Souls (1993). There’s a classical structure beneath the layers of artistry and design that feels as timeless as films about New York, and certainly, Soul feels like one of those as well. Docter’s stroke of genius is making the film’s Earth scenes, marked by a luminescent realism, feel more astonishing and richly animated than the various spirit realms. It’s a concept that goes back to the aforementioned Powell and Pressburger film, whose scenes in Heaven took place in black-and-white, while the scenes on Earth took place in Technicolor. The film’s answers to our questions about the meaning of life arrive in the form of color and sensation. Beyond its sillier humorous notes and efficient, fast-paced explanations of complex worlds, Soul rewards contemplation. Even after multiple viewings, one suspects that the film will only continue to reveal intricate details and further layers to its form-follows-function structure. It’s also the kind of experience that will deepen as younger viewers grow and recognize its truth, while adults still have time to learn from its message.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review