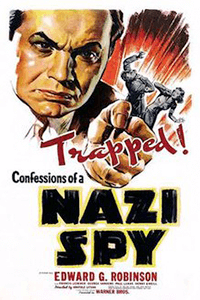

Confessions of a Nazi Spy

By Brian Eggert |

(Note: Warner Archive has released Confessions of a Nazi Spy on Blu-ray for the first time. Order the disc from Amazon here.)

Before the Japanese Imperial Army attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States maintained an isolationist stance about the war in Europe and the looming menace of Nazism. After Adolf Hitler took power over Germany in 1933, rumors spread of his Nazi party’s anti-Semitic agenda. The Nazi threat to the world became more evident with the Anschluss of Austria in 1938. Still, the US kept out of the conflict. Even so, Hollywood studios found veiled ways of confronting fascism, most commonly through allusion and historical parallels. But Anatole Litvak’s Confessions of a Nazi Spy marked a defining moment by speaking out against Nazism directly. Produced in 1939 by Warner Bros., the first studio to take an active anti-Nazi stance in the US and abroad, the film is the earliest example of a major studio confronting “Hitlerism”—just one of the many isms to be referenced in the film alongside “gangsterism” and in contrast to “Americanism.” Such ideological rhetoric prevails in many of the anti-Nazi films of the pre-Pearl Harbor period, including pictures that equate the gangsterism of domestic fascist groups with Nazism (see Black Legion, 1937). But the ideological underpinnings of Nazi Germany have a direct connection to their source in Litvak’s film. Confessions of a Nazi Spy would be the first of a small minority of pre-Pearl Harbor films that reveal how Nazis had already engaged in espionage against the United States, and in doing so, it supported an anti-isolationist position.

Unlike many pre-Pearl Harbor films that allude to the dangers of fascism—including Alfred Hitchcock’s spy-thrillers of the 1930s and many Warner Bros. productions—which could be described as message films for how they disguise of anti-Nazi themes, Confessions of a Nazi Spy is most transparently a message film. The sheer lack of entertainment value implies its status as part exposé, part documentary dramatization, and part newsreel feature. The film eschews the traditional dramatic formatting of a Hollywood feature. There is not, for instance, a protagonist with a conflict to overcome or a lesson to be learned. The story resists standard Hollywood structures, avoiding the lessons of Aristotle’s Poetics or Freytag’s pyramid, and it altogether ignores the traditional three-act structure deployed by nearly every feature during Hollywood’s Golden Age. Instead, the film seeks to inform the audience of a real-life Nazi threat to the United States and reinforce the anti-Nazi ideology maintained by Warner Bros. and its filmmakers. Yet, after the film, audiences would no longer be able to regard the Second World War from afar and ignore Nazis as Europe’s problem, given the film’s basis in fact.

In February 1938, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover announced that his office had uncovered a Nazi spy outfit working out of a German-American Bund in New York. But Hoover make the information public prematurely, as not all members of the spy ring had been apprehended. The German-American Bund had been responsible for spreading anti-Semitic and pro-Nazi material to German-Americans throughout the country. They supported the precepts of the Nazi ideology, and even greeted each other with their motto, “Sterb ein Jude” or “Let the Jew die.” The FBI’s case broke when Guenther Rumrich, a naturalized US citizen recruited by Nazi intelligence, attempted to acquire US passports for Nazi agents by impersonating a secretary of state. Authorities captured him, and his cooperation led to a reduced sentence and the conviction of three spies working for the Nazis. Leon G. Turrou, the agent who uncovered the ring, quickly turned around and sold the story to The New York Times, and then, alongside reporter David G. Wittels, co-authored a book about the case in 1938. Their book, Nazi Spies in America, became a bestseller and gained national attention. It was too much attention, however, as Hoover filed charges against Turrou, whose book potentially swayed the jurors on the still-open case. Though Hoover eventually dropped the charges against Turrou, he fired the agent, suspecting that he accepted bribes from Dr. Ignatz Greibl, an alleged Nazi agent who fled to Germany when the case broke.

According to historian Michael E. Birdwell’s book Celluloid Soldiers: Warner Bros.’s Campaign Against Nazism, Harry Warner began discussing a film adaptation almost immediately after hearing news of Nazi spies in the United States. In the late 1930s, Warner made several speeches declaring his studio’s anti-Nazi position and intent to make a picture that depicted the truth about the Nazi ideology and what went on in concentration camps. For a time, he wanted to produce a film called Concentration Camp that would depict what then had only been rumored to take place in the Nazi death camps. But after receiving pressure from other studio heads and Joseph Breen, head of the Production Code Administration’s enforcement division, Warner abandoned the project. Meanwhile, studios like MGM, Paramount, and Twentieth Century-Fox still worked with the Nazis to maintain their place in the German marketplace, while also accusing Warner Bros. of “righteous rage” and feeling “somehow responsible for the fate of European Jewry.” Regardless, the title was used by Russian filmmaker Aleksandr Macheret in his cheaply made Concentration Camp (1938), a poorly received feature imported into the US in 1939. The film was hardly the exposé Warner sought to make, as Concentration Camp avoids detailing the mass genocide or anti-Semitism of the Nazis and instead follows a group of Soviet inmates as they proudly maintain their Communist solidarity against their fascist enemy.

According to historian Michael E. Birdwell’s book Celluloid Soldiers: Warner Bros.’s Campaign Against Nazism, Harry Warner began discussing a film adaptation almost immediately after hearing news of Nazi spies in the United States. In the late 1930s, Warner made several speeches declaring his studio’s anti-Nazi position and intent to make a picture that depicted the truth about the Nazi ideology and what went on in concentration camps. For a time, he wanted to produce a film called Concentration Camp that would depict what then had only been rumored to take place in the Nazi death camps. But after receiving pressure from other studio heads and Joseph Breen, head of the Production Code Administration’s enforcement division, Warner abandoned the project. Meanwhile, studios like MGM, Paramount, and Twentieth Century-Fox still worked with the Nazis to maintain their place in the German marketplace, while also accusing Warner Bros. of “righteous rage” and feeling “somehow responsible for the fate of European Jewry.” Regardless, the title was used by Russian filmmaker Aleksandr Macheret in his cheaply made Concentration Camp (1938), a poorly received feature imported into the US in 1939. The film was hardly the exposé Warner sought to make, as Concentration Camp avoids detailing the mass genocide or anti-Semitism of the Nazis and instead follows a group of Soviet inmates as they proudly maintain their Communist solidarity against their fascist enemy.

Warner Bros. purchased the film rights to Turrou’s book in 1938 with a promise not to release the film until after the open trial concluded. Not long after the Warners announced the project, Georg Gyssling, a German consul based in Los Angeles and installed by Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, wrote to Breen to have the production stopped. Gyssling had been a devoted Nazi since 1931 and served as a Hollywood influencer from 1933 to 1941, often taking his orders directly from Goebbels. Gyssling demanded that Breen use his influence to bar the production, or else Hollywood would face penalties from the German market. Breen, inclined to approve the anti-Nazi material given its basis in fact— despite his being an anti-Semite—ignored Gyssling’s letter and approved the production. In response, Gyssling and the German-American Bund tried to intimidate the Warners and producer Hal B. Wallis to shut down the production, issuing death threats, menacing phone calls, and physical intimidation. Warner Bros. increased security on the studio lot, treated the script like a top-secret document, and wrapped the production in the span of six weeks.

The script for Confessions of a Nazi Spy was written by John Wexley and directed by the Ukrainian-born Litvak, who, like many international directors at this time, fled Europe after Hitler’s rise to power. The production’s screen story follows the real-life account with impressive accuracy, aside from a few name changes, preachy lines of dialogue, and narrative conveniences to whitewash the FBI’s mistakes. Paul Lukas plays Dr. Kassell, a villainous character based on the escaped Dr. Greibl. Kassell gives heated speeches to his devoted German-American Bund that attempt to redefine Americanism with Nazi values. His rhetoric in an early scene promotes isolationism, resolving that democracy and racial equality can only result in chaos. If the character’s Nazism was not enough, Kassell is also portrayed as a philanderer with a jealous wife at home. Kassell also receives orders on his approach from an unnamed Nazi official in Germany, who looks suspiciously like Joseph Goebbels, played by Martin Kosleck:

“National Socialism in the United States must wrap itself in the American flag. It must appear to be a defense of Americanism. But at the same time, our aim must always be to discredit conditions there in the United States. And in this way make life in Germany admired and wished for. Racial and religious hatred must be fostered on the basis of American-Aryanism. Classism must be encouraged in a way that the labor and the middle classes will become confused and antagonistic. In the ensuing chaos, we will be able to take control […] From now on your watchword will be ‘America for Americans,’ but never forget that National Socialism is the hammer not the anvil. This new Americanism is a formless iron that we will beat into another swastika.”

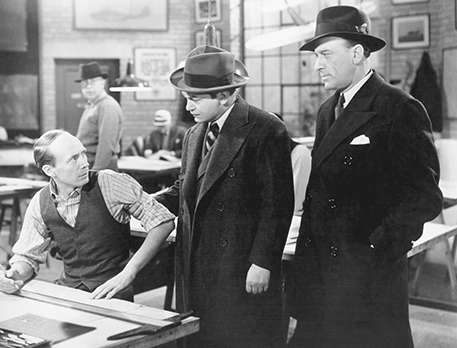

The film renames Guenther Rumrich as Kurt Schneider (Francis Lederer), a Bundist with money problems who writes to Nazi officials in hopes of becoming a paid infiltrator. While the Nazis hire Schneider, British Intelligence officers intercept Schneider’s written correspondence to his handlers and notify the FBI of Schneider’s activities. Edward G. Robinson reached out to Warner Bros. to play FBI Agent Ed Renard, the movie’s stand-in for Turrou, hoping the G-Man role would proudly represent his Jewishness and anti-Nazi position. Although top-billed and featured prominently on the studio’s publicity material for the film, Robinson does not appear for nearly an hour into this 89-minute feature. Renard, a nobler version of Turrou, captures the weak-minded, sniveling Schneider and interrogates him, leading to an easy confession and the capture of several spies. In Renard’s scenes, the film portrays Nazis as fueled by hate and intent on a US takeover, but it also reveals their spy ring as simplistic, suggesting the superior counter-forces of the United States can easily prevent the Nazis’ brand of villainy. Additionally, the film takes liberties with Kassell’s escape, suggesting Nazi agents forced him back to Germany to receive a fate worse than the American justice system: a Nazi death sentence. Rather than noting the FBI’s poor treatment of the case that led to many Nazi spies evading capture—ironically, through the publication of Turrou’s book—the film gives the viewer solace in Kassell’s grim fate.

The film renames Guenther Rumrich as Kurt Schneider (Francis Lederer), a Bundist with money problems who writes to Nazi officials in hopes of becoming a paid infiltrator. While the Nazis hire Schneider, British Intelligence officers intercept Schneider’s written correspondence to his handlers and notify the FBI of Schneider’s activities. Edward G. Robinson reached out to Warner Bros. to play FBI Agent Ed Renard, the movie’s stand-in for Turrou, hoping the G-Man role would proudly represent his Jewishness and anti-Nazi position. Although top-billed and featured prominently on the studio’s publicity material for the film, Robinson does not appear for nearly an hour into this 89-minute feature. Renard, a nobler version of Turrou, captures the weak-minded, sniveling Schneider and interrogates him, leading to an easy confession and the capture of several spies. In Renard’s scenes, the film portrays Nazis as fueled by hate and intent on a US takeover, but it also reveals their spy ring as simplistic, suggesting the superior counter-forces of the United States can easily prevent the Nazis’ brand of villainy. Additionally, the film takes liberties with Kassell’s escape, suggesting Nazi agents forced him back to Germany to receive a fate worse than the American justice system: a Nazi death sentence. Rather than noting the FBI’s poor treatment of the case that led to many Nazi spies evading capture—ironically, through the publication of Turrou’s book—the film gives the viewer solace in Kassell’s grim fate.

Confessions of a Nazi Spy does not look like other Hollywood pictures of the period. Litvak strived for realism by incorporating bold imagery into the production, including newsreel footage, scenes from Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1935), images of well-known Nazis like Goebbels, and an animation of a global map overcome by a swastika. Kaleidoscopic montage sequences depict the Nazi machine, overlaying footage of marching soldiers and swastika flags onto the floating heads of enraged Nazi generals barking an unheard diatribe. Such images are accompanied by an omniscient narrator, speaking like the announcer in a newsreel broadcast, who explains the Nazi worldview to the audience as if Harry Warner himself had written it: “The Nazi Party has created a new fascist society based on a devout worship of the Aryan supermen, a new fascist culture imbued with a glorification of conquest and war. A fascist system of life where every man, woman, and child must think alike, speak alike, and do alike.” The film also suggests that Nazis believe Americans to be a “simple-minded people,” a jab that would certainly place viewers on the defensive, creating an antagonistic relationship between Nazism and Americanism.

Despite such potent descriptions, Litvak strived for realism, even in the dramatic scenes, making it difficult for the viewer to distinguish reality from Hollywood creation. In addition to using actual trial testimonies in the climactic court case sequence, the production’s research department took photos of the actual New York courtroom where the trial took place. The studio also hired actors because they looked like actual Nazi figureheads, such as Kosleck’s resemblance to Goebbels. But all the realism is capped by a dramatized scene that ungainly forces the message of Confessions of a Nazi Spy with the subtlety of a public service announcement. In the final scene, Agent Renard and the prosecuting attorney, Kellogg (Henry O’Neill), talk over the case. Their exchange emphasizes the dangers of the Nazi threat, and thus an isolationist perspective, linking the two ideas with madness no less. Renard remarks:

“Funny thing working a case like this for so long. It’s like spending a great deal of time in a madhouse. You see these Nazis operating here and you think of all those in Germany, you can’t help feeling somehow that they’re, well, absolutely insane […] As a matter of fact, you begin to doubt your own sanity. We see what’s happening in Europe. We know what they’re trying to do here. It all seems so unreal, fantastic. Like an absurd nightmare. Absurd. But when you think of its potential menace, it’s terrifying.”

Following Renard and Kellogg’s conversation, “America the Beautiful” plays against the end credits of Confessions of a Nazi Spy, and with that, Warner Bros. achieved its rallying cry. By detailing the real-life case of Nazi espionage against the United States, the film provides a look at Nazi methods to corrupt American minds; it presents the Nazi ideology as calculating, hateful, and un-American; and it defines America as free of dangerous isms (Ward Bond plays an American Legion member who announces to the Bundists, “We don’t want any isms in America but Americanism”). Moreover, as Birdwell notes, Confessions of a Nazi Spy was the first Hollywood film to characterize Nazis through a series of behaviors, gestures, and stereotypes—all of which were based on actual footage and still signify Nazis today. Never before had a film portrayed German and German-American characters alike giving the sharp Nazi salute, accompanied by a loud “Sieg Heil!” Also new were the trappings of typical Nazi set design: massive portraits of Hitler, omnipresent swastikas, the Gestapo, and Hitler Youth rallies. Fortunately, the film is careful to note the presence of sympathetic, non-Nazi Germans in the United States to create a distinction between many German-Americans and Nazi adherents.

Nevertheless, a frenzy of violent reactions and bad reviews greeted Confessions of a Nazi Spy upon its debut on April 27, 1939—more than four months before Hitler invaded Poland— enough to generate the headlines Warner Bros. sought for its first anti-Nazi motion picture. Fascist groups, Nazi sympathizers, and German consuls in the US appealed to censorship boards to prevent its release; however, both local and national boards refused to bar the film from exhibition. German-Americans in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, burned the local Warner Bros. theater to the ground, and members of the German-American Bund described the film as proof of a Jewish conspiracy in Hollywood. In Poland, exhibitors were hanged outside of their theaters for showing the film. Critics praised the film’s politics but censured its methods. The New York Times reviewer wrote, “Hitler won’t like it; neither will Goebbels; frankly, we were not too favorably impressed either,” explaining “its editorial bias, however justified, has carried it to several childish extremes.” As it turns out, Goebbels was impressed. He considered himself proud to appear in a Hollywood picture but also dismissed the film’s danger to the Nazi Party in his diary: “It arouses fear in our enemies rather than anger and hate.” Perhaps most disappointing to the Warners, American audiences were not altogether interested. Confessions of a Nazi Spy was not a major hit for the studio and provided just enough box office to avoid being called a financial failure.

Nevertheless, a frenzy of violent reactions and bad reviews greeted Confessions of a Nazi Spy upon its debut on April 27, 1939—more than four months before Hitler invaded Poland— enough to generate the headlines Warner Bros. sought for its first anti-Nazi motion picture. Fascist groups, Nazi sympathizers, and German consuls in the US appealed to censorship boards to prevent its release; however, both local and national boards refused to bar the film from exhibition. German-Americans in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, burned the local Warner Bros. theater to the ground, and members of the German-American Bund described the film as proof of a Jewish conspiracy in Hollywood. In Poland, exhibitors were hanged outside of their theaters for showing the film. Critics praised the film’s politics but censured its methods. The New York Times reviewer wrote, “Hitler won’t like it; neither will Goebbels; frankly, we were not too favorably impressed either,” explaining “its editorial bias, however justified, has carried it to several childish extremes.” As it turns out, Goebbels was impressed. He considered himself proud to appear in a Hollywood picture but also dismissed the film’s danger to the Nazi Party in his diary: “It arouses fear in our enemies rather than anger and hate.” Perhaps most disappointing to the Warners, American audiences were not altogether interested. Confessions of a Nazi Spy was not a major hit for the studio and provided just enough box office to avoid being called a financial failure.

Among the other few pre-Pearl Harbor anti-Nazi films that warned of Nazi threats in the United States, few editorialized events from the headlines like Confessions of a Nazi Spy. Instead, they chose to dramatize the idea of Americans being corrupted by the influence of the Nazi ideology. Subsequent films showed Nazis as capable of sneaking into the United States and causing trouble, or worse, converting Americans to their cause. Before Joel McCrea battled Nazis in Foreign Correspondent (1940), he exposed Nazi spies operating in the United States in Lloyd Bacon’s Espionage Agent, a Hitchcockian romance and another Warner Bros. picture released just a few months after Confessions of a Nazi Spy in 1939. In RKO’s “B” production of Jack Hively’s They Made Her a Spy (1939), Sally Eilers plays a woman compelled to become a government agent when Nazi spies kill her brother. But Confessions of a Nazi Spy’s influence was most apparent on the Twentieth Century-Fox release World Premiere (1941). Director Ted Tetzlaff’s comedy featured a frantic John Barrymore as a movie producer trying to prevent two Nazis and an Italian fascist from stopping the debut of his anti-Nazi production, called “The Earth in Flames,” in Washington.

With films like these, American audiences were attuned to the Nazi threat on the home front long before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Today, movies like Confessions of a Nazi spy register as propagandistic. However, the difference between this Warner Bros. production and anti-Nazi films made after Pearl Harbor is that, after the US was drawn into the war, the Hollywood studios worked in tandem with the government to create propaganda and sell war bonds. Confessions of a Nazi is a rarity because the studio and filmmaker felt impassioned to address Nazism and include their social viewpoints in the film. Based on a true story and committed to the facts of the case, the film shares a ripped-from-the-headlines account and only slightly changes details for dramatic effect. Confessions of a Nazi remains an affront to the US’s isolationist stance, a commercial risk for Warner Bros., and a challenge to the purely entertaining mode of Hollywood cinema. Although clearly biased and heavy-handed in its methods, its exposé quality sought to create awareness and alert audiences to the very real threat of Nazi espionage in America in the late 1930s. If the approach robs the film of dramatic resonance today, it continues to be a telling historical marker and evidence of a Hollywood studio taking a moral and political stance when it was unpopular to do so.

Bibliography:

Birdwell, Michael E. Celluloid Soldiers: Warner Bros.’s Campaign Against Nazism. New York University Press, 1999.

Bordwell, David, et al. The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Columbia University Press, 1985.

“A Byte Out of History: Spies Caught, Spies Lost, Lessons Learned.” Federal Bureau of Investigation, 3 December 2007. https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/news/stories/2007/december/espionage_120307. Accessed 24 February 2018.

Doherty, Thomas. Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939. Columbia University Press, 2013.

Smertenko, Johan Jacob. “Hitlerism Comes to America.” Harper’s Magazine, November 1933. https://harpers.org/archive/1933/11/hitlerism-comes-to-america/. Accessed 24 February 2018.

Urwand, Ben. The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler. Yale University Press, 2013.

(Note: The above essay was excerpted and re-edited from a Master’s thesis, An Undeclared War: Hollywood’s Pre-Pearl Harbor Anti-Nazi Cinema.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review