The Definitives

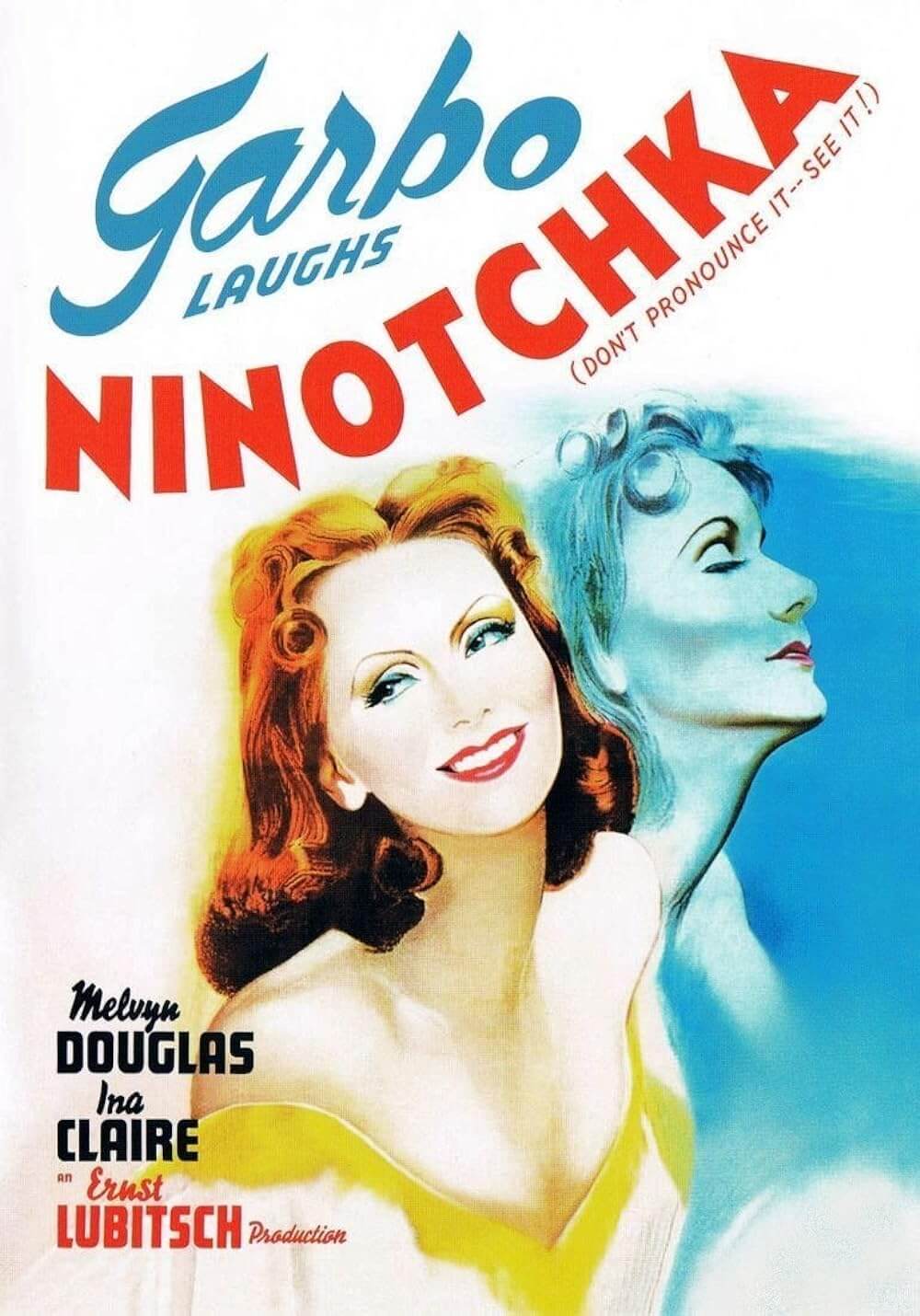

Ninotchka

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Has there ever been a more charming, sexy, infectious laugh put to film than the one Greta Garbo delivers in Ninotchka? And yet, it comes from the “Swedish Sphinx” of the Silent Era, an actress whose career was defined almost exclusively by heavy dramatic roles. Garbo’s onscreen persona was cemented by her legendary “Garbo Mystique,” a quality of inscrutable but alluring erotic perception largely of her own design, further perpetuated by her presence in austere dramas such as Anna Karenina (1935) and Camille (1937). A performer of unmatched style and beauty, her line “I want to be alone” from Grand Hotel (1932) fortified her reclusive front and her enduring fascination. The deeply private actress had, since her 1924 debut in the Swedish picture The Saga of Gosta Berling, remained ever secretive about her private life and retained a strong disdain for publicity. Throughout her career until her retirement in 1941, Garbo gave few interviews, refused to sign autographs or participate in publicity for her films. She was a consummate artist, an actress ahead of her time, and her refusal to bow to the usual demands of a Hollywood celebrity only enhanced her status as an icon among both the media and her adoring public.

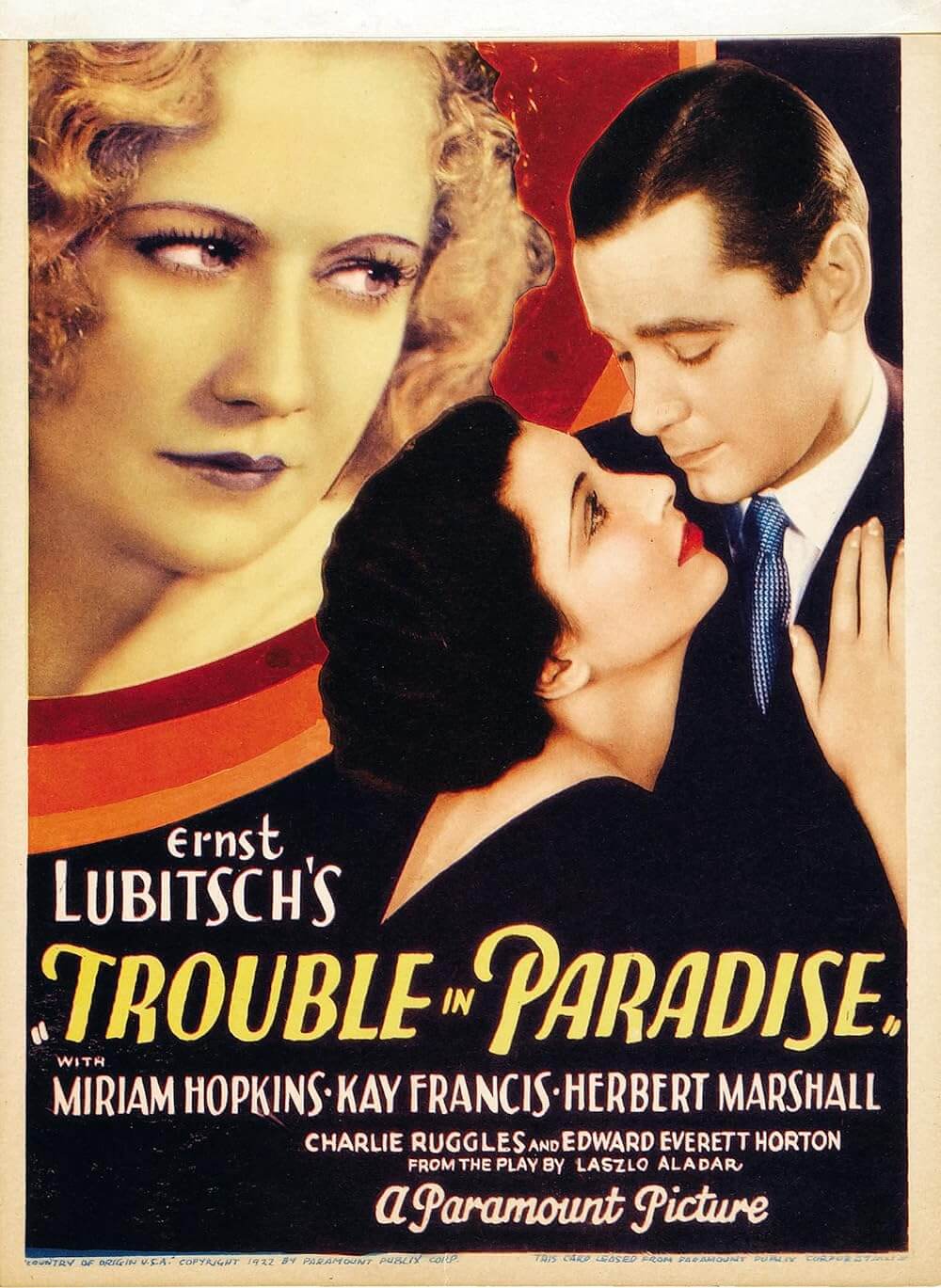

Who better to shatter this mystique, or at least shed one of its many layers, than Ernst Lubitsch, the German-born Polish director whose sophisticated romantic comedies were filled with frivolities and wit? French master Jean Renoir said that Lubitsch “invented the modern Hollywood,” and indeed American films would borrow from the director’s signature “Lubitsch Touch” for years. With titles like Trouble in Paradise (1932) and Design for Living (1933), Lubitsch’s cosmopolitan stylization pressed the Production Code’s boundaries by sneaking crafty innuendo and social messages just under the noses of the censors. As an artist-humorist, he was unparalleled and greatly admired by Garbo, who wanted her first screen appearance in a comedy to be with an artist like Lubitsch. And Hollywood’s most celebrated director would have no trouble at all convincing the silver screen’s biggest, most withdrawn star to appear in one of his pictures. After all, MGM had long wanted to attach its moody star to a comedy; in fact, they already had the tagline which read “Garbo Laughs!” and echoed the promotions for her first Talkie, Anna Christie (1930), advertised with the line “Garbo Talks!” But what project could ever entice the elusive actress into such a risky departure from her usual onscreen image?

After MGM made it known they wanted to make a Garbo comedy, writer Melchior Lengyel pitched his idea with just three little sentences: “Russian girl saturated with Bolshevist ideals goes to fearful, Capitalistic, monopolistic Paris. She meets romance and has an uproarious good time. Capitalism not so bad after all.” The broad strokes of the idea were based in part on Tovarich, a 1933 play by French writer Jacques Deval, adapted into English by Robert E. Sherwood, and in 1937 made into a motion picture by Anatole Litvak starring Charles Boyer and Claudette Colbert. Boyer and Colbert play a Russian Prince and Grand Duchess who escape the Russian Revolution to Paris, hiding out in disguise as a butler and housemaid for a wealthy Parisian family. MGM loved the idea and paid Lengyel fifteen thousand dollars for his three sentences; Garbo agreed on the condition that she be directed by a true artist rather than a studio workhorse. Originally, the studio hired George Cukor to direct, but he soon backed out to devote more time to Gone With the Wind. Garbo gave the studio two choices: Edmund Goulding (her director on Grand Hotel) or Lubitsch. Garbo’s close friend Salka Viertel, co-writer on a handful of Garbo pictures, had already been hired to co-write the script with Lengyel, but Lubitsch rejected their efforts; he also rejected a draft by S.N. Behrman. In their place, Lubitsch chose to hire Walter Reisch, his screenwriter from That Uncertain Feeling (1941), and later added scribe Charles Brackett and his co-writer-and-not-yet-director Billy Wilder (Brackett and Wilder would go on to make The Major and the Minor (1942), The Lost Weekend (1945), and Sunset Boulevard (1950) together).

After MGM made it known they wanted to make a Garbo comedy, writer Melchior Lengyel pitched his idea with just three little sentences: “Russian girl saturated with Bolshevist ideals goes to fearful, Capitalistic, monopolistic Paris. She meets romance and has an uproarious good time. Capitalism not so bad after all.” The broad strokes of the idea were based in part on Tovarich, a 1933 play by French writer Jacques Deval, adapted into English by Robert E. Sherwood, and in 1937 made into a motion picture by Anatole Litvak starring Charles Boyer and Claudette Colbert. Boyer and Colbert play a Russian Prince and Grand Duchess who escape the Russian Revolution to Paris, hiding out in disguise as a butler and housemaid for a wealthy Parisian family. MGM loved the idea and paid Lengyel fifteen thousand dollars for his three sentences; Garbo agreed on the condition that she be directed by a true artist rather than a studio workhorse. Originally, the studio hired George Cukor to direct, but he soon backed out to devote more time to Gone With the Wind. Garbo gave the studio two choices: Edmund Goulding (her director on Grand Hotel) or Lubitsch. Garbo’s close friend Salka Viertel, co-writer on a handful of Garbo pictures, had already been hired to co-write the script with Lengyel, but Lubitsch rejected their efforts; he also rejected a draft by S.N. Behrman. In their place, Lubitsch chose to hire Walter Reisch, his screenwriter from That Uncertain Feeling (1941), and later added scribe Charles Brackett and his co-writer-and-not-yet-director Billy Wilder (Brackett and Wilder would go on to make The Major and the Minor (1942), The Lost Weekend (1945), and Sunset Boulevard (1950) together).

The story follows Garbo’s severe Nina Ivanovna Yakushova, nicknamed Ninotchka, an envoy sent to Paris to check the progress of three chummy comrades—Iranov (Sig Ruman), Buljanov (Felix Bressart), and Kopalsky (Alexander Granach)—tasked with selling jewels appropriated during the Russian Revolution of 1917 for the betterment of the state. In Paris, the exiled Russian Grand Duchess Swana (Ina Claire) stakes a claim to the jewels and sends her would-be lover, the suave and aristocratic playboy Count Léon d’Algout (Melvyn Douglas), to postpone the sale until the matter can be resolved in the courts. Meanwhile, the Count easily tempts the three Soviets with all the accouterments of their fine Parisian hotel and the surrounding city. Ninotchka is not so easily charmed, at first anyway. But her icy exterior is melted away as she takes in the sights and, albeit reluctantly, unwinds, gradually falling in love not only with Paris but the Count. At first, he tries to crack her frozen exterior with bad jokes and frivolous behavior, until finally, she breaks when he accidentally falls off a chair in a small eatery. Her laughter is a pleasure to behold, and their ensuing romance continues through Parisian couture, champagne, and dancing. The Grand Duchess, jealous over the Count’s fawning over Ninotchka, presents the second act’s crisis when she offers to give Ninotchka her country’s jewels if she leaves Paris and the Count. Duty-bound, Ninotchka agrees and, back in frigid Moscow, resumes her professional life. Only when the Count tracks her down does she finally realize that she can no longer live for her country, and instead must live for her love.

Production began in May of 1939 and continued for eight weeks. Although Lubitsch had convinced Garbo to play Ninotchka—complete with a drunk scene the actress dreaded performing—he struggled to control her elusive technique. In fact, Garbo’s borderline method acting involved inhabiting a role emotionally, a progressive style for the era. Through subtle gestures and delicate eye movements, she communicated a limitless degree of emotion, and her style seemed especially if not exclusively suited for cinema. Of Garbo, Wilder remarked, “What was it about that face? …You could read into it all the secrets of a woman’s soul. She became all women on the screen. Not on the sound stage. The miracle happened in that film emulsion. Who knows why?” As for Lubitsch, who famously acted out and dictated how his actors should perform their roles, the director failed to develop a connection with his leading lady. Garbo preferred directors who let her alone to work her magic, however self-conscious about it she may have been. Lubitsch at least understood her needs, but later conflicting stories suggested Garbo remembered him to be, in some reflections, “like a loving father” and in others “a vulgar little man” who worked at a faster pace than she was accustomed. Casting Claire as the Grand Duchess Swana also presented an awkward on-set dynamic; Garbo and Claire’s husband at the time, actor John Gilbert, had a very public affair while filming Flesh and the Devil in 1926.

Production began in May of 1939 and continued for eight weeks. Although Lubitsch had convinced Garbo to play Ninotchka—complete with a drunk scene the actress dreaded performing—he struggled to control her elusive technique. In fact, Garbo’s borderline method acting involved inhabiting a role emotionally, a progressive style for the era. Through subtle gestures and delicate eye movements, she communicated a limitless degree of emotion, and her style seemed especially if not exclusively suited for cinema. Of Garbo, Wilder remarked, “What was it about that face? …You could read into it all the secrets of a woman’s soul. She became all women on the screen. Not on the sound stage. The miracle happened in that film emulsion. Who knows why?” As for Lubitsch, who famously acted out and dictated how his actors should perform their roles, the director failed to develop a connection with his leading lady. Garbo preferred directors who let her alone to work her magic, however self-conscious about it she may have been. Lubitsch at least understood her needs, but later conflicting stories suggested Garbo remembered him to be, in some reflections, “like a loving father” and in others “a vulgar little man” who worked at a faster pace than she was accustomed. Casting Claire as the Grand Duchess Swana also presented an awkward on-set dynamic; Garbo and Claire’s husband at the time, actor John Gilbert, had a very public affair while filming Flesh and the Devil in 1926.

Beyond her famous desire for privacy, Garbo was reluctant to play scenes in front of others. Lubitsch called Garbo “probably the most inhibited person I ever worked with.” She refused to allow strangers or anyone non-essential to the scene at hand on the set while filming. This included screenwriters, although Wilder found a way to sneak on-set and watch the day’s progress. Garbo’s demand for a closed set even extended to the extras, forcing Lubitsch to shoot some Parisian crowd scenes separate and intercut them in post-production. Nevertheless, Lubitsch remained taken with her. He would later observe, “I have found that one of the difficulties in working with [actresses] is their slavish devotion to the mirror. In the eight weeks during which I worked with Garbo she never looked into the mirror once unless I told her to do so. Nobody but the film director can appreciate the significance of that.” Garbo’s shyness and extreme timidity on-set also led to the rumor that her eventual laugh in the film was subdued and therefore needed to be dubbed; however, Wilder and many others involved in the production have since confirmed the moment is genuine. It was Garbo who laughed.

Ninotchka completed shooting in July of 1939. Before the film’s premiere on October 6 of that year, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a nonaggression pact, prefiguring the same kind of offscreen political parallels to the onscreen satire shared by another Lubitsch film, To Be or Not to Be (1941). Made for $1.3 million, in large part because of Garbo and Lubitsch’s considerable salaries, the film would make modest profits both domestically and abroad. Still, Louis B. Mayer, unhappy about the terms of MGM’s contract with Lubitsch, griped, “Ninotchka got everything but money.” Ninotchka went on to earn four Academy Award nominations—including Best Actress, Best Screenplay, and Best Picture—although it had the misfortune of competing against the landslide winner Gone with the Wind. Enthusiastic reviewers remarked on Garbo’s incredible performance and how Douglas’ role would have been better suited to a more romantic leading man, such as Cary Grant or William Powell, both of whom were originally considered for the role of the Count Léon d’Algout. Variety remarked on Lubitsch’s touch, saying, “There’s some bright and eyebrow-lifting dialogue, delivered in typical Lubitsch fashion.” The New York Herald Tribune commented on Garbo’s presence in a comedy by saying, “There is an added verve and color to her personality [that] makes her even more lovely than in the past.” The New York Times opened its review by declaring, simply, “Stalin won’t like it.”

Ninotchka completed shooting in July of 1939. Before the film’s premiere on October 6 of that year, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a nonaggression pact, prefiguring the same kind of offscreen political parallels to the onscreen satire shared by another Lubitsch film, To Be or Not to Be (1941). Made for $1.3 million, in large part because of Garbo and Lubitsch’s considerable salaries, the film would make modest profits both domestically and abroad. Still, Louis B. Mayer, unhappy about the terms of MGM’s contract with Lubitsch, griped, “Ninotchka got everything but money.” Ninotchka went on to earn four Academy Award nominations—including Best Actress, Best Screenplay, and Best Picture—although it had the misfortune of competing against the landslide winner Gone with the Wind. Enthusiastic reviewers remarked on Garbo’s incredible performance and how Douglas’ role would have been better suited to a more romantic leading man, such as Cary Grant or William Powell, both of whom were originally considered for the role of the Count Léon d’Algout. Variety remarked on Lubitsch’s touch, saying, “There’s some bright and eyebrow-lifting dialogue, delivered in typical Lubitsch fashion.” The New York Herald Tribune commented on Garbo’s presence in a comedy by saying, “There is an added verve and color to her personality [that] makes her even more lovely than in the past.” The New York Times opened its review by declaring, simply, “Stalin won’t like it.”

Politically, Ninotchka treads on delicate ground in its favor of Western culture and Capitalism over Communism, and the film was inevitably banned from several Soviet countries upon its release. The picture takes a bold step forward by representing Communism with some degree of realism for a Hollywood production. By further representing a woman of some power—though Ninotchka reports to a male, Bela Lugosi’s Commissar Razinin—as a significant member of the party. Wilder later observed that, while writing, he knew he could not avoid the truth when representing Communist Russia. The film’s depiction of Soviet life would not only break gender role taboos of the period, but it would present a serious-minded satire of the facts. In 1939, Russia was a needed ally, and so referencing Stalin’s Great Purge and Ninotchka’s five-year plans with a sense of humor represented an undeniable risk and required political awareness from the film’s audience. When Ninotchka first arrives in Paris, her three comrades ask, “How are things in Russia?” She replies coldly, “Very good. The last mass trials were a great success. There are going to be fewer but better Russians.” As Capitalism prevails, the message underneath the love story becomes clear, so much so that in 1948 the U.S. State Department sent 35 prints of Ninotchka to Italy during the “Red-threatened” elections in hopes of impacting voters.

Nevertheless, the film’s laissez-faire nature, characteristic of both Lubitsch and Wilder’s comedies, is cemented in the foreword: This picture takes place in Paris in those wonderful days when a siren was a brunette and not an alarm… And if a Frenchman turned out the light it was not on account of an air raid! To be sure, speaking to the director’s usual touches of sophisticated humor, Ninotchka is a Lubitsch brand comedy about sex. The protagonist’s stifled sexuality is represented by her political identity, and only when she sheds her Communist role can she fulfill herself sexually. Like all Lubitsch films, such themes are bubbling under the surface, where the comic gags and hilarious punch lines never cease in their gaiety. When Ninotchka goes into a Parisian restaurant and asks for raw beets and carrots, the server replies, “Madame, this is a restaurant, not a meadow.” And one of the more charming subplots involves Ninotchka’s estimation of Parisian fashion when she regards a frivolous hat, by the film’s costume designer Adrian, in a shop window. “How can such a civilization survive which permits their women to put things like that on their heads?” Later, she realizes the appeal of such things when she shows up at the Count’s door wearing the hat and receives his compliments on her outfit with a reserved, enamored smile.

Nevertheless, the film’s laissez-faire nature, characteristic of both Lubitsch and Wilder’s comedies, is cemented in the foreword: This picture takes place in Paris in those wonderful days when a siren was a brunette and not an alarm… And if a Frenchman turned out the light it was not on account of an air raid! To be sure, speaking to the director’s usual touches of sophisticated humor, Ninotchka is a Lubitsch brand comedy about sex. The protagonist’s stifled sexuality is represented by her political identity, and only when she sheds her Communist role can she fulfill herself sexually. Like all Lubitsch films, such themes are bubbling under the surface, where the comic gags and hilarious punch lines never cease in their gaiety. When Ninotchka goes into a Parisian restaurant and asks for raw beets and carrots, the server replies, “Madame, this is a restaurant, not a meadow.” And one of the more charming subplots involves Ninotchka’s estimation of Parisian fashion when she regards a frivolous hat, by the film’s costume designer Adrian, in a shop window. “How can such a civilization survive which permits their women to put things like that on their heads?” Later, she realizes the appeal of such things when she shows up at the Count’s door wearing the hat and receives his compliments on her outfit with a reserved, enamored smile.

Though her laugh is real and charming, Garbo’s finest moments in the picture involve the actress deliberately playing on her own sad persona. How could she not be aware that with every smile or double-entendre, she was, in a way, acting out a form of self-iconoclasm and therein completely reshaping her mystique? At first, she commands a deadpan comedy style, her character still very much devoted to the Soviet state. During one of Douglas’ advances on her character, she asks, “Must you flirt?” He smiles charmingly, “I don’t have to, but I find it natural.” She says tersely, “Suppress it.” Garbo walks through much of the picture like a machine, her performance as regimented as Ninotchka herself must be, layered with a prevailing sense of resistance and tragedy under the surface. The performance curiously aligns with Garbo herself and her offscreen reputation as an impenetrable, morose character. And yet, Garbo’s purported lover Mercedes d’Acosta noticed the actress’ mood improve while filming: “Never since I had known her had she been in such good spirits.” Her personal cheerfulness from working on a Lubitsch comedy comes through in the film, particularly in later scenes where, now in love, Ninotchka smiles and laughs alongside her beau and three jolly comrades. These scenes are so catching in their joy that it seems a shame Garbo had only this opportunity to perform in a Lubitsch comedy.

Greta Garbo’s penultimate screen appearance, the effervescent Ninotchka was followed by the best forgotten Two-Faced Woman in 1941, in which she also starred alongside Melvyn Douglas. After her last effort failed to attract audiences and her influence over MGM executives waned somewhat, she resolved to retire from Hollywood. With this decision, she forever ingrained herself as the personification of Hollywood’s Golden Age, altogether avoiding the sort of late-career missteps made by many of her contemporaries. With her undeniable glamour and puzzling erotic refinement forever locked in the public’s mind, Garbo went on to lead a secluded life. She lived out her remaining years in leisure, spent her days traveling throughout Europe, and retained a chic residence in Manhattan where “Garbo watchers” would occasionally spot her walking, until her death in 1990 at the age of 84. Of all her films, Ninotchka may not have emblemized her other roles where she played ill-fated lovers and fallen women. Still, it showed the joyful humanity behind the statuesque Hollywood beauty. Lubitsch’s film gives us strains of light satire, sexual intimation, and whimsical simplicity, but none of these pleasures compare to the delights found in Garbo’s laugh.

Greta Garbo’s penultimate screen appearance, the effervescent Ninotchka was followed by the best forgotten Two-Faced Woman in 1941, in which she also starred alongside Melvyn Douglas. After her last effort failed to attract audiences and her influence over MGM executives waned somewhat, she resolved to retire from Hollywood. With this decision, she forever ingrained herself as the personification of Hollywood’s Golden Age, altogether avoiding the sort of late-career missteps made by many of her contemporaries. With her undeniable glamour and puzzling erotic refinement forever locked in the public’s mind, Garbo went on to lead a secluded life. She lived out her remaining years in leisure, spent her days traveling throughout Europe, and retained a chic residence in Manhattan where “Garbo watchers” would occasionally spot her walking, until her death in 1990 at the age of 84. Of all her films, Ninotchka may not have emblemized her other roles where she played ill-fated lovers and fallen women. Still, it showed the joyful humanity behind the statuesque Hollywood beauty. Lubitsch’s film gives us strains of light satire, sexual intimation, and whimsical simplicity, but none of these pleasures compare to the delights found in Garbo’s laugh.

Bibliography:

Bainbridge, John. Garbo. New York: Doubleday & Co., 1955.

Eyman, Scott. Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise. New York: Simon & Schuster, c1993.

Paris, Barry. Garbo. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Walker, Alexander. Garbo: A Portrait. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1980.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review