The Definitives

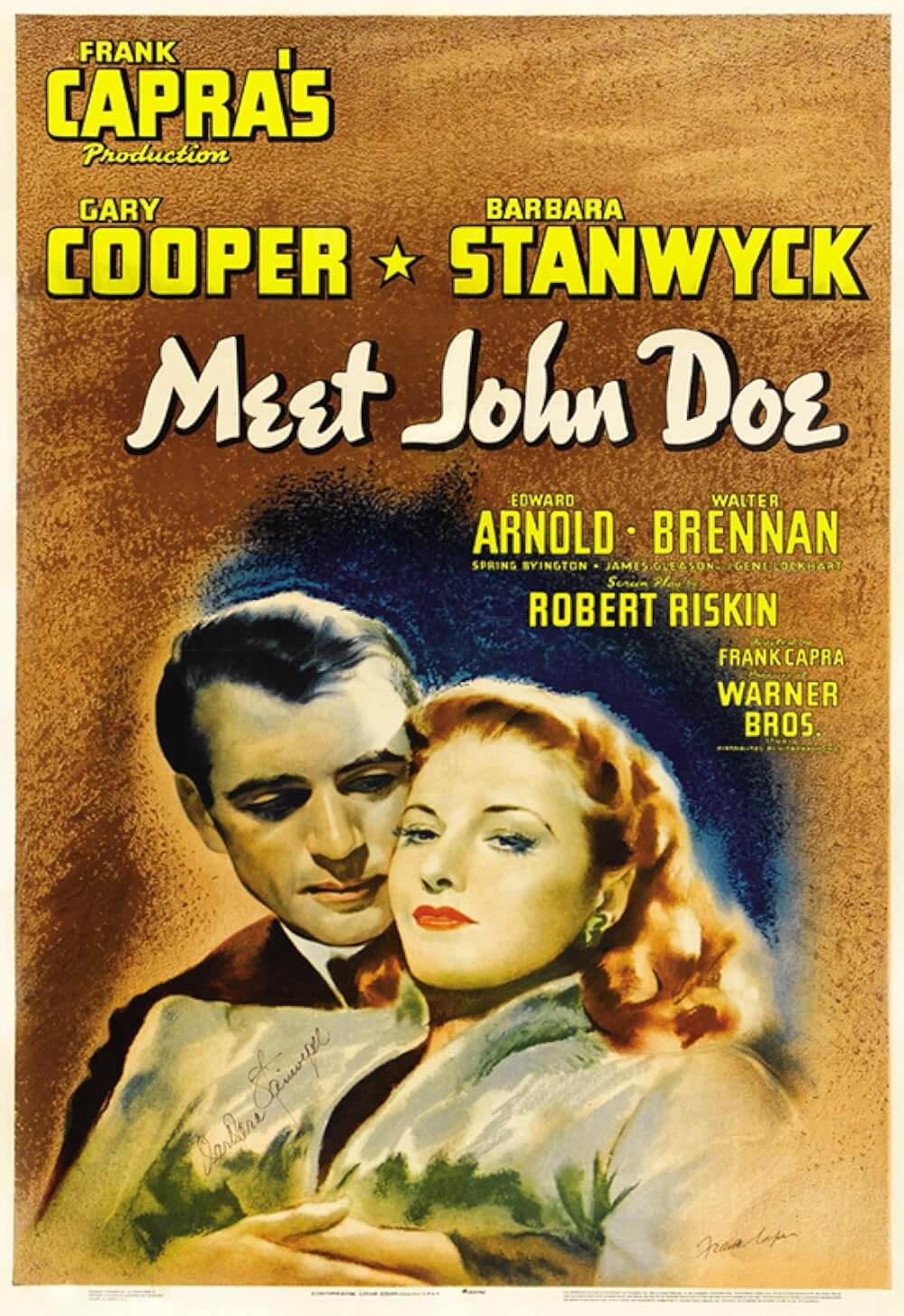

Meet John Doe

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Frank Capra kept an earnest faith in the American Dream. As a Sicilian immigrant, America had been good to him; he treasured the idealistic pledge of liberty and justice for all. During Capra’s height as a Hollywood filmmaker, a period lasting the decade of the 1930s, the American Dream was always under siege from threats such as the Great Depression, the rise of fascism in the United States, or the rumblings of the Second World War. With the country on the verge of collapse and its foundational standards disintegrating, many Americans were losing hope. Capra’s most popular films sought to counteract this decline with stories that spoke to people in terms of the moral principles that drive the civic culture, bolstering national pride from its foundation in the average American moviegoer. But his artistic ambitions were sometimes confronted, even contradicted by his devotion to that audience, his need to please, make us laugh, and warm our hearts. Capra was sentimental and politically idealistic, a profoundly humanistic filmmaker who told stories about people with an unshakable belief in their country and the goodness of the everyday American because he, too, had an unshakable belief in America. He dealt with serious issues the only way he knew how: through the magic of classic Hollywood filmmaking. In his films, Capra brought his characters to unbelievable lows, revealing the depths of corruption and greed at the heart of American politics and business, but he always reestablished some measure of order to the universe, an idea personified by the average American. Indeed, Capra’s inner cynic and optimist were always at odds.

Reflecting the countless contradictions in his work, Meet John Doe is perhaps Capra’s most self-reflective film. His 1941 picture acknowledges that politicians and the mass media can sway the American people; such institutions could, in the wrong hands, threaten the liberty of the individual with their mass-produced culture. Yet, the film puts forth an unwavering belief that the average American is decent and kind, and it does so through arguably the most powerful mass-produced communication device of the twentieth century. The discrepancy in Capra’s work remains that his faith in the individual was betrayed by his understanding that cinema could be used to communicate ideas. Capra was a populist, and Meet John Doe embraces this, sometimes in uneasy ways. Even so, the film represents a singular example of his patriotic approach, a method that relies less on sound theory and intellectual readings than the galvanizing emotions of his characters. Meet John Doe is the work of a passionate filmmaker whose most famous films have been said to exemplify what it means to be an American. Then again, perhaps he exaggerated, if not fabricated an American myth with Meet John Doe and other titles such as Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), You Can’t Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). As John Cassavetes once remarked, “Maybe there never was an America in the thirties. Maybe it was all Frank Capra.”

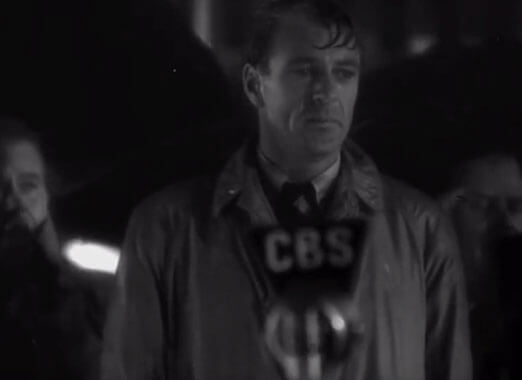

In Meet John Doe, Barbara Stanwyck plays Ann, a reporter whose paper is taken over by corporate interests; the stone words “Free Press” are jackhammered off the façade and replaced with a shiny metal placard reading “The New Bulletin” in the opening scenes. When she’s laid off and told to deliver her final column, Ann, disgruntled, authors a rabble-rousing article under the pseudonym John Doe, declaring a protest of “slimy politics” and “the state of civilization.” Unless things change, she ghostwrites in Doe’s words, he will commit suicide on Christmas Eve. The column quickly gains the attention of local politicians and newspapers, and Ann concocts a plan to save her job by pitching an ongoing John Doe column to her editor (James Gleason). They need a face to match Ann’s words, and so they hire the bewildered Long John Willoughby (Gary Cooper), a former amateur baseball player who has fallen on hard times. The newspaper puts Willoughby, along with his hobo friend, known as the Colonel (Walter Brennan), up in a posh hotel room, where they pass the time pantomiming a baseball game. Ann continues to write passionate letters in Doe’s name, espousing a simple philosophy based “on friendliness; on giving, not taking; on helping your neighbor and expecting nothing in return.” Inspired by Doe’s words, which Ann drew from her late father, people across the country who are “lonely and hungry for something” form John Doe Clubs. They start behaving with empathy and kindness toward their neighbors, mounting protests “against our country closing its doors on the needy.” At the same time, Willoughby believes in and becomes the John Doe of Ann’s column, falling in love with her in the process.

In Meet John Doe, Barbara Stanwyck plays Ann, a reporter whose paper is taken over by corporate interests; the stone words “Free Press” are jackhammered off the façade and replaced with a shiny metal placard reading “The New Bulletin” in the opening scenes. When she’s laid off and told to deliver her final column, Ann, disgruntled, authors a rabble-rousing article under the pseudonym John Doe, declaring a protest of “slimy politics” and “the state of civilization.” Unless things change, she ghostwrites in Doe’s words, he will commit suicide on Christmas Eve. The column quickly gains the attention of local politicians and newspapers, and Ann concocts a plan to save her job by pitching an ongoing John Doe column to her editor (James Gleason). They need a face to match Ann’s words, and so they hire the bewildered Long John Willoughby (Gary Cooper), a former amateur baseball player who has fallen on hard times. The newspaper puts Willoughby, along with his hobo friend, known as the Colonel (Walter Brennan), up in a posh hotel room, where they pass the time pantomiming a baseball game. Ann continues to write passionate letters in Doe’s name, espousing a simple philosophy based “on friendliness; on giving, not taking; on helping your neighbor and expecting nothing in return.” Inspired by Doe’s words, which Ann drew from her late father, people across the country who are “lonely and hungry for something” form John Doe Clubs. They start behaving with empathy and kindness toward their neighbors, mounting protests “against our country closing its doors on the needy.” At the same time, Willoughby believes in and becomes the John Doe of Ann’s column, falling in love with her in the process.

But as the Colonel warns, the newspaper business is run by a bunch of corrupt “heelots,” no different than the banks and politicians. “The world’s been sheared by a drunken barber,” he says, urging Willoughby not to trust Ann or the newspaper. Meanwhile, the newspaper’s publisher D. B. Norton (Edward Arnold) schemes to use John Doe’s fame to form a third-party political campaign and take the White House. “What the American people need is an iron hand,” says Norton, who plans to rally the silent majority in the John Doe Clubs and use Willoughby as his personal mouthpiece. But before Norton’s plot can take hold, Willoughby realizes how Norton has used him. It’s all the more painful because he planned to propose to Ann. An often-overlooked aspect of Meet John Doe is the touching relationship between Ann and Willoughby (though it reinforces the old-fashioned idea that every young woman wants to marry her father), particularly in the scene where Willoughby stumbles around his proposal to Ann by confirming the matter with her mother (Spring Byington). When Willoughby discovers he’s being used by both Norton and Ann, he plans to tell the truth to people at a rally. Norton beats him to it, feigning honesty by exposing Willoughby as a paid figurehead. The crowd quickly turns on Willoughby, throwing tomatoes and rain-soaked newspapers. Exposed, Willoughby resolves to prove his faith to John Doeism by committing suicide, leaping to his death on Christmas Eve as promised in the first John Doe column. But he’s stopped at the last minute by Ann, who loves him back, and a small group of John Doe followers, who coax him from the ledge and urge him to carry on inspiring the country with a message in which he now wholeheartedly believes.

Meet John Doe stands as Capra’s most self-reflexive work, as both he and Willoughby question their role as a speaker to a countrywide audience, while they also ask whether or not they are worthy of the attention. Born in Palermo in 1897, Capra was just 6-years-old when his family moved to the United States. After arriving on Ellis Island, they hopped a train to Los Angeles, where the young Capra sold newspapers in the Italian ghetto. During this time, he developed an unwavering appreciation for the opportunities afforded his family in their new country. He attended the California Institute of Technology and earned a degree in engineering. Afterward, he enlisted to fight in the First World War, but he contracted the Spanish flu that had wiped out tens of millions in the pandemic of 1918, earning him a discharge. When he returned home, Capra made ends meet with a series of odd jobs—from salesperson to professional poker player—that developed his talent as a huckster. Using his skills as a pitchman, he conned his way into the film business, passing himself off as a professional to get his first job in San Francisco as the director of a single-reel silent. Soon after, he went to work for Hal Roach as a gagman, then Max Senet as a screenwriter of Charlie Chaplin’s copycat, Harry Langdon (Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, 1926). Capra eventually signed a long-term contract with Harry Cohn at CBC Film Sales Corporation, before the studio changed its name to the more prestigious sounding Columbia Pictures. After little more than a decade, he became one of the most renowned, recognized, and awarded filmmakers of his day.

At Columbia, Capra directed a series of pictures alongside his collaborator, Robert Riskin, screenwriter of Capra’s The Miracle Woman (1931), Platinum Blonde (1931), American Madness (1933), Lady for a Day (1933), It Happened One Night (1934), Broadway Bill (1934), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and You Can’t Take It with You. Their pictures earned more than twenty Academy Award nominations, including statues for both Capra and Riskin. Of course, it didn’t hurt that Capra helped legitimize the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. What started as a banquet dinner attended by a few self-congratulatory Hollywood elite was transformed into a national sensation under Capra’s leadership as the Academy president between 1935 and 1939. Capra and Riskin’s collaboration supplied a foundation to the contradictions apparent in Meet John Doe and, to a greater extent, the director’s career. With Riskin, Capra made his most successful pictures, but the two men often quarreled off-screen because of their ideological differences. Capra was a staunch conservative Republican, while Riskin’s views leaned liberal, and their collaborations contain evidence of both influences. To be sure, Meet John Doe runs counter to some of Capra’s politics, from his republicanism to his refusal to vote for John F. Kennedy to his defending of Richard Nixon as late as 1981 (Nixon “wasn’t stealing any great money,” the director rationalized). Capra and Riskin’s shared body of work resulted in films that could be argued as representative as either side, but rather than divide the audience, they seemed to bring everyone together.

At Columbia, Capra directed a series of pictures alongside his collaborator, Robert Riskin, screenwriter of Capra’s The Miracle Woman (1931), Platinum Blonde (1931), American Madness (1933), Lady for a Day (1933), It Happened One Night (1934), Broadway Bill (1934), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and You Can’t Take It with You. Their pictures earned more than twenty Academy Award nominations, including statues for both Capra and Riskin. Of course, it didn’t hurt that Capra helped legitimize the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. What started as a banquet dinner attended by a few self-congratulatory Hollywood elite was transformed into a national sensation under Capra’s leadership as the Academy president between 1935 and 1939. Capra and Riskin’s collaboration supplied a foundation to the contradictions apparent in Meet John Doe and, to a greater extent, the director’s career. With Riskin, Capra made his most successful pictures, but the two men often quarreled off-screen because of their ideological differences. Capra was a staunch conservative Republican, while Riskin’s views leaned liberal, and their collaborations contain evidence of both influences. To be sure, Meet John Doe runs counter to some of Capra’s politics, from his republicanism to his refusal to vote for John F. Kennedy to his defending of Richard Nixon as late as 1981 (Nixon “wasn’t stealing any great money,” the director rationalized). Capra and Riskin’s shared body of work resulted in films that could be argued as representative as either side, but rather than divide the audience, they seemed to bring everyone together.

Scholars, such as Capra biographers Joseph McBride and Raymond Carney, frequently note the contradictory value systems at work in Capra’s films, requiring “complex acts of narrative repression and selection” by the viewer to negotiate each film. Even Capra’s autobiography, called The Name Above the Title—as he was one of the first directors to have that honor alongside D.W. Griffith, Cecile B. DeMille, and Alfred Hitchcock—shows evidence of a man unwilling to dissect the political meaning of his work with any detail, perhaps for fear of what he might discover about himself or his output. He sought approval and success from his audience and his industry, but he resented having to succumb to the demands of Columbia and its need to produce crowd-pleasers. Capra had darker and more severe themes he wanted to explore about corruption, rising political tensions, and despair, but he learned, after two of his purely dramatic films bombed—The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932) and Lost Horizon (1937)—that he remained in the good graces of both Cohn and the American moviegoer by delivering laughs and a happy ending. Audiences didn’t want high-mindedness, especially not in the 1930s; they wanted to escape. It was Capra’s need to explore the grim aspects of the American experiment, combined with commercial cinema’s demand for escape, that defined Capra’s films with their occasionally dreamy optimism in the face of staggeringly pessimistic odds.

Throughout his life, Capra struggled with depression, self-doubt, and the persistent fear that he was a phony—a quality he explores in Meet John Doe. “Capra, like Doe, seems to be torn,” wrote Charles J. Maland. “Who is he (the Sicilian immigrant, the ex-ballplayer) to be the national spokesman of values, communicating to millions through the media?” Watch the scene at the rally when the audience turns on Doe and shouts “Impostor!” at him. It’s as though Capra has orchestrated his worst fear on the screen. But after a few disappointments—as well as backlash from politicians surrounding the release of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, a film distributed under an air of controversy for its suggestion that an American senator could be corrupt—Capra became acutely aware that people, especially a crowd, could quickly transform into an angry mob. He bore a dogged faith in people (“The typical American who can keep his mouth shut,” says one character in Meet John Doe) and a steady distrust of them (“Show me an American who can keep his mouth shut and I’ll eat him,” says another from the same film). With a crowd so volatile and subject to whim, Capra came to understand that an audience could be duped just as easily as they could turn against you. He continuously worried that he would be exposed and seen as a fraud, and rather than risk vilification, he sought to appease his audience. And this disparity between Capra’s life and his work reflects the autobiographical nature of his output, and how many Capra heroes are reflections of their creator.

If Meet John Doe mirrors its director’s insecurities more than his earlier films, it may be because it was Capra’s first independent production. Capra’s twelve-year contract with Columbia Pictures had just expired, marking an end to the most successful, productive, and profitable era of his career. It was also a tumultuous period, where Capra was answerable to Cohn for every creative choice that resulted in a commercial uncertainty or failure. Unsure where to go next (he could have gone anywhere) and reluctant to sign another long-term contract after his experience with Cohn, he turned down offers from Samuel Goldwyn and David O. Selznick, among others. Instead, he teamed with Riskin, who became the vice president of Frank Capra Productions, Inc., the short-lived production company whose only notable credit was Meet John Doe. Capra believed wholeheartedly in the auteur theory long before the term was ever coined, having written a series of articles beginning in 1936 about the ideal of a “one man, one film” production with the director leading the show. For their first project under this ideal, Riskin proposed an adaptation of the short story “A Reputation” by Richard Connell, published in the August 1922 issue of Century Magazine. It had already been worked into a screen treatment in 1939 by Connell and Robert Presnell called “The Life and Death of John Doe,” which Capra read and enjoyed. Riskin set out to write the screenplay, while Capra sought a distributor.

If Meet John Doe mirrors its director’s insecurities more than his earlier films, it may be because it was Capra’s first independent production. Capra’s twelve-year contract with Columbia Pictures had just expired, marking an end to the most successful, productive, and profitable era of his career. It was also a tumultuous period, where Capra was answerable to Cohn for every creative choice that resulted in a commercial uncertainty or failure. Unsure where to go next (he could have gone anywhere) and reluctant to sign another long-term contract after his experience with Cohn, he turned down offers from Samuel Goldwyn and David O. Selznick, among others. Instead, he teamed with Riskin, who became the vice president of Frank Capra Productions, Inc., the short-lived production company whose only notable credit was Meet John Doe. Capra believed wholeheartedly in the auteur theory long before the term was ever coined, having written a series of articles beginning in 1936 about the ideal of a “one man, one film” production with the director leading the show. For their first project under this ideal, Riskin proposed an adaptation of the short story “A Reputation” by Richard Connell, published in the August 1922 issue of Century Magazine. It had already been worked into a screen treatment in 1939 by Connell and Robert Presnell called “The Life and Death of John Doe,” which Capra read and enjoyed. Riskin set out to write the screenplay, while Capra sought a distributor.

At first, the production was announced as a Selznick International release with James Stewart and Jean Arthur, stars of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, leading the cast. The Selznick deal never happened. Instead, Jack Warner advanced Capra nearly half of the budget, plus the use of the studio facilities, in exchange for twenty-five percent of the box-office. The rest of the production was financed through the Bank of America, who had developed a practice of taking film negatives as collateral to ensure payment. Capra decided on Gary Cooper to play the resident common man, requiring Warners to negotiate a deal with Samuel Goldwyn for the actor: they paid $200,000 and lent out Bette Davis for MGM’s production of The Little Foxes in exchange for Cooper’s services. For Ann, Capra turned to Stanwyck, who had become a star in his early films The Miracle Woman and Forbidden (1932). Edward Arnold, the standard heavy in Capra’s stock, having appeared in You Can’t Take It with You and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, was the obvious choice for Norton. Principal photography took place in the summer of 1940, and the film was released the following May. Critics were lukewarm on the film compared to other Capra efforts, and the box-office receipts hardly proved the financial viability of Capra and Riskin’s independent company, which they dissolved at the end of 1941 when the director joined the Signal Corps to direct war films for the U.S. government.

After the war, Capra and Riskin liquidated and sold all rights to Meet John Doe, including the camera negative, to an independent distributor named Sherman K. Krellberg, whose Goodwill Pictures failed to maintain its copyright over the film. Unlike Columbia’s inventory of Capra pictures, which were lovingly preserved and maintained over the years even as Columbia was sold to Sony, Krellberg allowed his copy of Meet John Doe to deteriorate and his ownership to expire. In 1969, the film entered the public domain, where cheap copies were made of the original print. The American Film Institute stepped in and restored the film, working from prints in both Krellberg and Warners possession, before submitting their restoration to the Library of Congress. Regardless, Meet John Doe remains an underseen Capra picture compared to the director’s work at Columbia, in part due to the poor-quality prints still circulated and the limited presence of a better restoration on home entertainment platforms. Cinephiles can more readily access Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life or Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, but not Meet John Doe, as these films have had proper restorations and distribution over the years. Even today, consumers and cinephiles may struggle to locate a sharp, clean restoration, thus they are less likely to rediscover one of Capra’s best films.

Meet John Doe reads like a compendium of Capra’s preoccupations, themes, and symbolism found in his other films. McBride noted Capra’s persistent theme surrounding a “Gary Cooperish man who practices the Christian virtues of poverty and brotherhood in the midst of the modern metropolis.” But the Christian imagery doesn’t end there. Capra’s repeated motif of a Christlike figure, from Jefferson Smith to George Bailey, find men willing to sacrifice themselves for the greater good of the people—Bailey and Willoughby even both attempt suicide on Christmas Eve. Willoughby resembles any number of the director’s heroes: men who have power, who must live up to the public trust, and who come close to corruption before setting themselves straight. Willoughby also recalls the women protagonists from The Miracle Woman and Lady for a Day, as both become subjects, if not pawns in a game between those pulling the strings and the masses (and in Capra’s films, large groups of people behave in a thoughtless manner, incapable of understanding or negotiating complex ideas). To these ends, Capra’s cast was essential, especially Cooper. Willoughby epitomizes the actor’s screen persona—the solid blank slate who intentionally underplayed his expressions and often stood for American values. Such roles were not uncommon for Cooper. Released a few months after Meet John Doe, Cooper appeared in Sergeant York for Howard Hawks, playing the national hero of the First World War. Years later in 1952, Cooper fought against American institutions that were poisonous to the country (such as McCarthyism) in High Noon.

Meet John Doe reads like a compendium of Capra’s preoccupations, themes, and symbolism found in his other films. McBride noted Capra’s persistent theme surrounding a “Gary Cooperish man who practices the Christian virtues of poverty and brotherhood in the midst of the modern metropolis.” But the Christian imagery doesn’t end there. Capra’s repeated motif of a Christlike figure, from Jefferson Smith to George Bailey, find men willing to sacrifice themselves for the greater good of the people—Bailey and Willoughby even both attempt suicide on Christmas Eve. Willoughby resembles any number of the director’s heroes: men who have power, who must live up to the public trust, and who come close to corruption before setting themselves straight. Willoughby also recalls the women protagonists from The Miracle Woman and Lady for a Day, as both become subjects, if not pawns in a game between those pulling the strings and the masses (and in Capra’s films, large groups of people behave in a thoughtless manner, incapable of understanding or negotiating complex ideas). To these ends, Capra’s cast was essential, especially Cooper. Willoughby epitomizes the actor’s screen persona—the solid blank slate who intentionally underplayed his expressions and often stood for American values. Such roles were not uncommon for Cooper. Released a few months after Meet John Doe, Cooper appeared in Sergeant York for Howard Hawks, playing the national hero of the First World War. Years later in 1952, Cooper fought against American institutions that were poisonous to the country (such as McCarthyism) in High Noon.

Commentator Alistair Cooke wrote upon the release of Mr. Deeds Comes to Town that Capra doomed himself when he “started to make movies about themes instead of people.” To some extent, Cooke correctly observes a growing trend in Capra’s films, as Meet John Doe offers an indictment of the fascistic ideologies that were emerging in the United States and around the world in the years leading up to the U.S. finally joining the Second World War after the attack on Pearl Harbor. With the character of Norton, Capra doubtless sought to call out William Randolph Hearst, who openly supported Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, if not draw comparisons between Norton and Hitler himself (Norton’s Motor Corps, for instance, recall Hitler’s storm troopers). But then, Norton is a figurehead that could be representative of any number of Capra’s list of American antagonists: the banks, money itself, or the fatcats running America—“heelots” all, in the Colonel’s view. McBride noted Capra’s “reactionary idealization” that the average American, particularly those less fortunate or situated in small towns, should maintain a healthy suspicion of the “cynical city” and its institutions. What Capra fails to recognize is that fascists, his target with Meet John Doe, spread similar messages of distrust for institutions. They break down the establishment to erect their own, more easily controlled power system. Hitler and Benito Mussolini discredited the media, censored ideas that diverged from the party line, and created their own propaganda departments, while Donald Trump proclaims “fake news” to any media outlet that does not support his ideas and praises those that do. Capra’s most prominent films demand that audiences keep to their principles, suggesting that anyone behind a microphone has an angle and anyone listening is a stooge. The irony, of course, is that his message is communicated by John Doe, a man behind a microphone, by way of Capra addressing his audience from the platform of cinema. The director warns that the media and public opinion can be manipulated in Meet John Doe, a film that uses cinema to disseminate his message.

But perhaps the ending of Meet John Doe is Capra’s way of admitting that his message is more important than the person, despite building Willoughby as a Christ-like figure for much of the film. Quite famously, Capra and Riskin could not reconcile their film’s ending; they shot three endings in all and conceived several others in hopes of discovering a conclusion that would serve the film’s two masters—Capra’s artistic intent and the ticket-buying audience. At first, Capra wanted Willoughby to follow through with his suicide, which would seal his martyrdom and embolden his message. Two of the three endings shot featured Willoughby following through with killing himself, but preview audiences found it unsatisfying. The conclusion that exists in the film features Willoughby talked down from the ledge by Ann, who tells him, “You don’t have to die to keep the John Doe ideal alive. Someone already died for that once. The first John Doe. And he’s kept that ideal alive for nearly 2,000 years.” Responding to the ending, Capra scholars from McBride to Richard Schickel have described it as a betrayal of what came before, suggesting that Capra had refused to commit to an ending that would have drawn a line in the sand, thus he sacrificed his artistic integrity to ensure box-office success. In his autobiography, Capra admits that Meet John Doe was conceived as a response to his perceived sentimentalism (dubbed “Capra-corn”) and to acquire critical praise: “Riskin and I would astonish critics with contemporary realities: the ugly face of hate; the power of uniformed bigots in red, white, and blue shirts; the agonist of disillusionment.” But there’s a sizeable gap between making a critical success and a film that resonates with an audience enough to earn a profit.

Capra was ever the commercial-minded sentimentalist, equally concerned with turning a profit as he was unprepared to betray the audience’s faith in moviegoing by killing fan-favorite Gary Cooper. Though his initial intent of the film was to appease “intellectual critics,” Capra would get a greater sense of validation from his audience, and deep down, perhaps he knew that. Even today, reviewers tend to dismiss the ending as a mixed message, completely illogical, or an unbelievable fantasy in the context of the film. But John Doe’s choice to remain alive and fight for his now-solidified beliefs is a quintessential Capra ending that brings the protagonist to the brink but not over it. This is the trajectory of The Miracle Woman, American Madness, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and It’s a Wonderful Life. Would the ending have been better if John Doe had jumped to his death? Perhaps, in a dramatic and even artistic sense. Then again, the lesson to Capra’s audience would have been that, when the world reeks of corruption, the noble path leads to self-sacrifice to demonstrate your firm beliefs. Dying for the country that had served him so well was certainly something Capra was prepared to do—he enlisted in the First World War as a soldier and volunteered himself to shoot war footage and make propaganda films during the Second World War. But such an ending would break with Capra’s sensibilities as an entertainer, and it’s a message that would prove unsuitable for audiences of the era, who needed reassurance and broad inspirational messages. Ultimately, had Willoughby killed himself, Meet John Doe would not have felt like a Frank Capra film.

Capra was ever the commercial-minded sentimentalist, equally concerned with turning a profit as he was unprepared to betray the audience’s faith in moviegoing by killing fan-favorite Gary Cooper. Though his initial intent of the film was to appease “intellectual critics,” Capra would get a greater sense of validation from his audience, and deep down, perhaps he knew that. Even today, reviewers tend to dismiss the ending as a mixed message, completely illogical, or an unbelievable fantasy in the context of the film. But John Doe’s choice to remain alive and fight for his now-solidified beliefs is a quintessential Capra ending that brings the protagonist to the brink but not over it. This is the trajectory of The Miracle Woman, American Madness, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and It’s a Wonderful Life. Would the ending have been better if John Doe had jumped to his death? Perhaps, in a dramatic and even artistic sense. Then again, the lesson to Capra’s audience would have been that, when the world reeks of corruption, the noble path leads to self-sacrifice to demonstrate your firm beliefs. Dying for the country that had served him so well was certainly something Capra was prepared to do—he enlisted in the First World War as a soldier and volunteered himself to shoot war footage and make propaganda films during the Second World War. But such an ending would break with Capra’s sensibilities as an entertainer, and it’s a message that would prove unsuitable for audiences of the era, who needed reassurance and broad inspirational messages. Ultimately, had Willoughby killed himself, Meet John Doe would not have felt like a Frank Capra film.

Meet John Doe might be reduced to a work of feel-good escapism, complete with a few laughs, a little romance, and a crowd-pleasing ending. Capra never resisted an easy joke or a tug on the heartstrings, but his light touch also makes his social consciousness bearable to a wide audience. As other critics and scholars have pointed out, Capra has made better films. But none of them represent Capra so well. “I wanted to glorify the average man,” Capra once said, “not the guy at the top, not the politician, not the banker, just the ordinary guy whose strength I admire.” Meet John Doe maintains a heartfelt belief that the average person has a chance against oppressive systems of political, financial, and social power, even while acknowledging what Schickel observed as Capra’s “affection for ordinary Americans, and his fear of them.” If his characters behave in inconsistent ways, it is only to provide the audience with some measure of reassurance before leaving the world of the film and returning to a harsh reality. Richard Jewell wrote that Capra made films “grounded in the belief that the average American was smart, principled and kindhearted and that these character traits would enable him/her to win out no matter the resources of the adversaries or the seeming hopelessness of the predicament.” Meet John Doe wrestles with Capra’s unwavering love of the American ideal and his understanding that people could too easily be led to corrupt it. His work affirms Americans’ worst fears about our institutions and ourselves. But Capra also offers a brief escape from reality and a message of hope before sending us back into a corrupt world, revitalized and prepared to endure, and in doing so, he wields the most essential power of classic Hollywood cinema

Bibliography:

Capra, Frank. The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography. Macmillan, 1971.

Carney, Raymond. American Vision: The Films of Frank Capra. Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Glatzer, Richard; Raeburn, Jon. Frank Capra: The Man & His Films. University of Michigan Press, 1975.

Maland, Charles J. Frank Capra. Twayne Pub, 1980.

McBride, Joseph. Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. University of Mississippi Press, 1992.

Poague, Leland. Another Frank Capra. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review