The Definitives

Ugetsu

Essay by Brian Eggert |

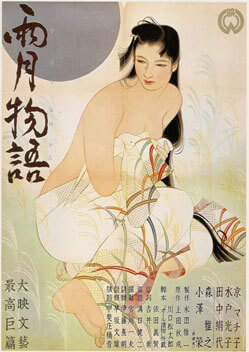

A mixture of social realism and otherworldly fantasy, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu takes place during a time of civil war in sixteenth-century Japan. The director’s sweeping tale of earthly humanity and spectral apparitions considers the fates of women during wartime. Wives become victims to the ambitions of their husbands and the cruelty of men, while their ghosts remain behind, haunted and unable to rest. The 1953 film, among the first to introduce the rest of the world to Japanese cinema, is a ponderous antiwar effort, informed by traditional Japanese art: scroll painting, noh theater, ghost stories, and biwa music. Mizoguchi’s use of such Japanese artforms in his aesthetic characterizes his visual elegance and refined approach. But his personal obsessions layer his work through a poetic treatment of a realistic social commentary. Ugetsu laments the suffering experienced, by women above all, in times of conflict, through sociopolitical subjugation, and within cultural systems. As a historical filmmaker, Mizoguchi explored suffering with the utmost accuracy in regard to the rich details of his productions, including sets, props, costumes, and behaviors, often laboring over the style of a kimono or actor’s expression in a given scene. At the same time, he paid particular attention to the inner being of his characters to ensure an emotional accuracy within his performers. Mizoguchi’s blend of historicity, artistic refinement, and human observation combines with his rare embrace of the spiritual in Ugetsu, and its effect is entrancing, affecting, and unforgettable.

Few decisive English-language studies have been written about Mizoguchi, though he often ranks among the great masters of cinema. His Japanese contemporaries (like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu) have had exhaustive texts written about them, but not Mizoguchi. Could this be, simply, because Mizoguchi has been called the “most Japanese” of all his countrymen-directors, and therefore his films resonate less with Western audiences? Or could it be that Western film historians have trouble identifying what are decidedly Japanese cultural, narrative, and aesthetic preoccupations? Though, as a cineaste, Mizoguchi enjoyed European and Hollywood films—evidenced by his enthusiastic appraisals of Italian Neorealism, Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1937, distributed in Japan in 1948), and Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941)—his primary influences resulted from Japan’s history of painting, literature, and music, in particular the former. He trained in Japanese watercolor painting, and his films were deeply influenced by the painting styles of artists ranging from portraitist Kitagawa Utamaro (1756-1806) to modern landscape painter Ryuzaburo Umehara (1888-1986). Mizoguchi’s influences resulted in an elegant style and execution, reflecting Japan’s long-held tradition of polished formalism and sophisticated aesthetic spectacle. Demonstrative of this style were Mizoguchi’s predominant socially conscious dramas about women.

Kenji Mizoguchi was born in 1898 in Tokyo to humble parents, the second child after an older sister, Suzu. His father was a carpenter who went bankrupt in 1905 after a bad business deal, leading to a series of formative events in Mizoguchi’s life: his family moved from a bourgeois home in Tokyo to a rundown neighborhood in Asakusa, near the red-light district; the addition of a younger brother made finances even more restraining; and due to their situation, his parents sold Suzu into the geisha trade. Suzu nonetheless played an important role in her brother’s life, securing him an apprenticeship designing kimono patterns in a factory. She eventually went on to marry well—a leading member of the Matsudaira line, a powerful family descendant from daimyo, rulers from feudal times—having a successful enough life to take her brothers in when their mother died in 1915. The following year, Mizoguchi enrolled at the Aoibashi Yoga Kenkyuko art school where he studied painting; he also studied opera at the Royal Theater in Akasaka before 1917, when his sister once again helped him secure a post, this time at a newspaper designing ads. In the subsequent years, Mizoguchi befriended a young actor with contacts at Nikkatsu film studio, where he designed costumes and sets but hoped to become an actor. Instead, a post opened for Mizoguchi to train as an assistant director under Eizo Tanaka in 1920.

Kenji Mizoguchi was born in 1898 in Tokyo to humble parents, the second child after an older sister, Suzu. His father was a carpenter who went bankrupt in 1905 after a bad business deal, leading to a series of formative events in Mizoguchi’s life: his family moved from a bourgeois home in Tokyo to a rundown neighborhood in Asakusa, near the red-light district; the addition of a younger brother made finances even more restraining; and due to their situation, his parents sold Suzu into the geisha trade. Suzu nonetheless played an important role in her brother’s life, securing him an apprenticeship designing kimono patterns in a factory. She eventually went on to marry well—a leading member of the Matsudaira line, a powerful family descendant from daimyo, rulers from feudal times—having a successful enough life to take her brothers in when their mother died in 1915. The following year, Mizoguchi enrolled at the Aoibashi Yoga Kenkyuko art school where he studied painting; he also studied opera at the Royal Theater in Akasaka before 1917, when his sister once again helped him secure a post, this time at a newspaper designing ads. In the subsequent years, Mizoguchi befriended a young actor with contacts at Nikkatsu film studio, where he designed costumes and sets but hoped to become an actor. Instead, a post opened for Mizoguchi to train as an assistant director under Eizo Tanaka in 1920.

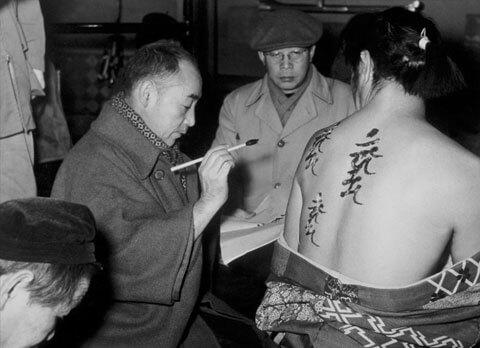

A strike at the studio meant Mizoguchi secured his first solo directing job on The Resurrection of Love in 1923. Once he became a director, he could spend more time researching subjects that interested him—kabuki and noh theater styles, literature from the world over, along with various styles of Japanese music and dance. Traditionalism became extremely important to the director, and his confident knowledge of traditional arts informed his cinema. He went on to make several Meiji Period films and earned a reputation for offering little insight or direction to his actors, beyond telling them to experience the inner being of their characters. He was a women’s filmmaker from the start, and quite by accident. Friend and mentor Minaru Marata had established himself for directing male-centric films; out of the pure commercial prospects, Mizoguchi was asked to make films about women. Drawing from his violent father and profound empathy for his mother and sister, Mizoguchi approached his subjects with a manner befitting his temperament: sensitive, with a rare aptitude for emotional insight. To be sure, friends and colleagues noted he was susceptible to bouts of displacement, sometimes removing himself from his career for a year at a time just to contemplate himself, his future. Although, he was also a great lover of women and prostitutes; infamously, he was stabbed in the back by a prostitute on a film set at the age of 27, an incident whose motivation remains a mystery.

After making dozens of programmers for various Japanese film studios during the first half of his career, Mizoguchi found his characteristic style in the late 1930s, marked by a rigorous attention to detail, a deliberate visual style, and humanist themes that often emphasized the sacrifices and harsh struggles endured by women. His films were unsparing in their depiction of the suffering women must endure, and he never glorified their beauty or treated them as objects; rather, he considered his female characters from a humanist perspective. In the history of Japan and its drama, women suffered needlessly under men but, culturally, were acquiescent to their fates. Women of the Meiji Period, for example, were required by law not to object to their subjectification. Sympathies aside, Mizoguchi’s method was exact. His reputation as a taskmaster solidified his assessment as an auteur among French writers in the Cahiers du cinéma, who celebrated Mizoguchi’s devotion to mise-en-scène and pristine aesthetics—which meant dozens of takes for his actors, precise and virtuoso camerawork, and a particular eye for detail. Famously, he had carpenters build a house set overnight for one of his films; in the morning, he felt it needed to be six feet to left. The carpenters rebuilt the house the next night, but again Mizoguchi thought the location was wrong. Only after a third and correctly situated set was built did shooting commence. Mizoguchi always remained on set to maintain a particular mood, going so far as to secretly urinate into bottles rather than leave to use the restroom. As many of his collaborators would attest, art was his life. All else was secondary.

Mizoguchi often told stories set in the past for the same reason as his more Westernized contemporaries such as Kurosawa or Masaki Kobayashi: the past’s ability to offer a reflector of the present. Sixteenth-century tales from the perspective of peasants and workers affected by the surrounding wars resonated with Mizoguchi. But for Ugetsu, he wanted to blend the supernatural with the realistic through a uniquely Japanese spiritual mix. Many Japanese follow both Shinto and Buddhism. The former involves the worship of a spiritual essence called kami, both a superior presence and an omnipresent force found in both animate and inanimate but natural objects. The latter concerns the spirits of former family members. The two combine into a belief that the ghosts of loved ones (usually) have an ever-present place among the living, whether they serve as guardians or something else. Though most Japanese ghost stories of Mizoguchi’s era tell of protective forces, today the more typical ghost is malicious with some lingering resentments toward the living. Before Hollywood reduced such stories to terms like “J-horror,” Japanese tales of the supernatural were called kaidan. Now commonly associated with scary tales of ghosts with an afterlife grudge, the traditional use of the term kaidan dates back to ancient stories compiled during the Edo period (1603–1868). Traditional kaidan were usually compiled into collections called kaidan-shif, what today might be called a horror anthology. Perhaps most famously, Masaki Kobayashi made Kwaidan in 1965, occupying the original form (and name) of kaidan anthologies with an impressive three-hour epic of horror.

Ugetsu takes the form of a kaidan anthology but interconnects two stories into a cohesive whole. After Genjuro (Mori Masayuki), a potter from the village of Omi, earns a massive payday selling his wares, he tries to convince his wife Miyagi (Tanaka Kinuyo) that they should rush another massive batch to take advantage of the market. Miyagi, who tends their home and mothers their young son Genichi, wants only that they remain “living together as a happy family.” Their neighbors, Miyagi’s sister Ohama (Mito Mitsuko) and her husband Tobei (Ozawa Eitaro), agree to assist Genjuro. Tobei hopes to use his portion of the profits to purchase his glory—he dreams of owning samurai armor and a spear, and then joining the civil war that sweeps the countryside. Even after soldiers invade Omi, robbing homes, dragging men away into forced labor, raping women, and killing others, Genjuro maintains “War’s good for business.” Genjuro’s business obsessions dominate his ambitions. As families scatter into the woods to hide, Genjuro resists abandoning his kiln, which is firing dozens of pots, plates, and cups—and if they cool too soon, the entire batch could be ruined. When the soldiers finally leave Omi, Genjuro and the others return to the village to find his kiln has cooled but the pottery inside is complete. They quickly gather the pottery, load it onto a boat, and then make for the market by way of Lake Biwa. Crossing the lake through a thick fog, they come across a stranded boatman who warns of pirates.

Their uncertainty about the dangerous journey ahead, mirrored by the haze around them, leads to a fateful decision: Genjuro, Tobei, and Ohama will continue on, while Miyagi and her son will be dropped off at the shore, where they will return home and wait for the others to return. On Miyagi’s way home, rogue samurai spear her to death and steal her food, leaving her son alive, clutching to her back. Meanwhile, unaware of Miyagi’s fate, Genjuro, Tobei, and Ohama sell the pottery for a hefty profit. Tobei quickly takes his portion, buys a sword, and attempts to join the war and achieve his glory—without a thought for his wife. Though clumsy and unprepared for battle, Tobei picks off a weak and vulnerable ronin, and then seeks the spoils of his victory. He receives a horse, armor, and vassals, and he immediately transitions from a cowering fool to a military character full of artificial pomp. At the same time, the abandoned Ohama finds herself cornered and gang-raped by a group of soldiers, who then deliver her to a brothel. Over time, she becomes an expert prostitute. One day, the newly dignified Tobei rides his vassals into a village. He grants them a reprieve at the local brothel. Inside, Tobei spots an experienced Ohama, clearly acclimated to her new vocation. He begs her forgiveness, vowing to restore her honor and set aside his military ambitions. She agrees, and together they return home to Omi.

During this time, Genjuro receives a massive pottery order from Lady Wakasa (Kyo Machiko), who has offered great compliments about his work. While at her home in Kuchiki manor—which soldiers ransacked long ago, killing all but Lady Wakasa and her servant—Genjuro falls under her spell. Enamored, Genjuro spends days with her, lost in bliss as if in a dream. They bathe together, make love, and soon agree to marry. But one day in town, Genjuro tells a man where he’s staying, and the man goes pale. A passing priest explains that Genjuro has been enchanted by a ghost. The priest offers to exorcize the “strange creature” by writing a Buddhist prayer on Genjuro’s skin. Upon his return, Lady Wakasa asks him never to leave again. But he reveals the prayers on his skin and says he wishes to return to his wife and child. Lady Wakasa confesses that she was killed before she could experience love and, having found it with him, now refuses to let him leave. Genjuro waves a sword to escape the manor and runs away, but he faints outside. The next day, he wakes to find the manor gone and nothing but ruins in its place. Genjuro resolves to return to Omi to find his family. He arrives in the evening to find Miyagi putting their son to bed. They embrace and, happy to be together again, sleep serenely through the night. The next morning, Genjuro wakes to find Miyagi gone. Villagers soon arrive and explain that Genichi had wandered back the night before, and that Miyagi had died. Genjuro realizes that Miyagi returned as a ghost to protect their son. He resolves to move on, making pottery alongside Tobei and Ohama, knowing that his wife is watching over them.

During this time, Genjuro receives a massive pottery order from Lady Wakasa (Kyo Machiko), who has offered great compliments about his work. While at her home in Kuchiki manor—which soldiers ransacked long ago, killing all but Lady Wakasa and her servant—Genjuro falls under her spell. Enamored, Genjuro spends days with her, lost in bliss as if in a dream. They bathe together, make love, and soon agree to marry. But one day in town, Genjuro tells a man where he’s staying, and the man goes pale. A passing priest explains that Genjuro has been enchanted by a ghost. The priest offers to exorcize the “strange creature” by writing a Buddhist prayer on Genjuro’s skin. Upon his return, Lady Wakasa asks him never to leave again. But he reveals the prayers on his skin and says he wishes to return to his wife and child. Lady Wakasa confesses that she was killed before she could experience love and, having found it with him, now refuses to let him leave. Genjuro waves a sword to escape the manor and runs away, but he faints outside. The next day, he wakes to find the manor gone and nothing but ruins in its place. Genjuro resolves to return to Omi to find his family. He arrives in the evening to find Miyagi putting their son to bed. They embrace and, happy to be together again, sleep serenely through the night. The next morning, Genjuro wakes to find Miyagi gone. Villagers soon arrive and explain that Genichi had wandered back the night before, and that Miyagi had died. Genjuro realizes that Miyagi returned as a ghost to protect their son. He resolves to move on, making pottery alongside Tobei and Ohama, knowing that his wife is watching over them.

As he explained in a note to longtime collaborator Yoshikata Yoda, Mizoguchi wanted to make a film about how “the violence of war unleashed by those in power on a pretext of the national good must overwhelm the common people with suffering—moral and physical.” To do this, Mizoguchi tells two intersecting stories drawn from several sources. The story of Genjuro and Miyagi was inspired by two of the nine stories in author Akirari Ueda’s 1776 collection Tales of Moonlight and Rain (Ugetsu Monogatari). Although the novel contains grotesque passages and other ghost stories, Mizoguchi chose only two, “The House in the Thicket” and “Lust of the White Serpent” (themselves based on Chinese novels). In the former, a farmer leaves home to sell his wares in Kyoto, where he’s robbed and falls ill. Years later, the farmer returns home to his wife, and they spend a pleasant evening together; only when the farmer wakes the next morning does he realize he spent the evening with his late wife’s ghost. In Lust of the White Serpent, a man seeks shelter from the rain inside a hut, where he meets a young woman. She lures him into her idyllic home and gives him a precious sword as a gift, but authorities later claim the sword was stolen from a shrine. When the man tries to introduce the authorities to the woman who gave him the sword, they inform him that she’s a ghost. Though the ghost seduces him and convinces him to get married, the man frees himself of her spell with the help of a priest, who, in turn, reveals the woman’s true form—a snake—and buries her. In both cases, Genjuro replaces Ueda’s protagonist; Miyagi serves as the forgotten wife, and Lady Wakasa is the ghost (but not a serpent).

Tobei and Ohama’s story was based on Guy de Maupassant’s 1883 novella Décoré, published in the collection Les Soeurs Rondoli. The original text follows an aspiring soldier who goes off to attain greatness, but in his absence, his wife beds an official to get her husband the coat of arms he desires. When he returns home, his wife gives him the official’s decorations and, being a dope, the husband believes he’s been awarded by his superiors. In the film, Tobei may be blinded by his ambitions, but in the end, he returns to Ohama after discovering her in a brothel. He reforms and sets aside his ambitions for a samurai’s armor and status, happily returning to their lives as peasants. This was not Mizoguchi’s preferred resolution, however; executives at the studio, Daiei Film Co. Ltd., insisted on a pleasant conclusion for at least one of the two central couples. The studio’s suggestions resulted in a comparatively optimistic, albeit still tragic, conclusion against Mizoguchi’s usual fatalism, especially surrounding his subjugated women characters. Matsutaro Kawaguchi and Yoshikata Yoda wrote the screenplay to Ugetsu, and Mizoguchi supervised their writing, providing precise instructions on its structure. At the same time, author Kawaguchi Matsutaro, who also served as director of the board at Daiei, penned a novelization.

The film was a success in Japan and for the studio, resulting in its distribution on the international festival circuit. A global appreciation of Japanese cinema did not develop until the 1950s—although, the Japanese film industry had flourished for decades. André Bazin, editor of France’s Cahier du Cinéma, wrote a 1955 essay called “The Lesson of Japanese Cinema Style,” which does not discuss Mizoguchi but remarks, “The beauty of their film reaches us with delay, like that of light from distant stars.” Throughout the 1950s, Japanese filmmakers like Kurosawa and Ozu won several international festival awards, and Mizoguchi was among them. The Venice Film Festival celebrated Mizoguchi early on, giving him the International Award in 1952 for The Life of Oharu; he also won the Silver Lion two years in a row, first for Ugetsu, then again for Sansho the Bailiff in 1953. Unfortunately, Mizoguchi died just three years after the release of Ugetsu, meaning, regardless of his awards, he would never go on to achieve the same level of commercial and artistic acknowledgment from a wider international audience. Those who championed Mizoguchi, such as Bazin and other writers on his film journal, did so, for the most part, looking back at the director after his death. Therefore, most of the serious analysis of Mizoguchi must be conducted through those who knew this inward man or have insight on Japanese filmmaking, history, and aesthetic traditions.

From the outset, Mizoguchi’s most apparent formal technique resides in his use of long takes. Extended shots often carry a balance between minimalism and virtuoso artistry. They seem minimalist for their lack of extravagant, fast-paced cutting that, by contrast to the rapid-fire editing of Hollywood cinema, occupies a slower visual rhythm—after all, cinema was first developed in the 1890s as a series of extended takes, while innovations of editing and montage arrived in the subsequent decades. The long take bears association to early silent films for that reason. The lack of edits to a Mizoguchi shot requires immersion and patience from an audience, gradually revealing its intimacy through a connection that it makes over time, through the viewer’s visual work in their act of watching, absorbing, and processing the entire length of an extended shot. Camera movements often differentiate an extended sequence or elaborate tracking shot depending on the context of a scene, such as their thrilling use in Welles’ Touch of Evil (1959) or Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948). Mizoguchi does not use long takes to thrill his audience, however, and his frequent one-scene-one-take method may result in an inattentive or impatient viewer. Still, as Mizoguchi’s enduring takes roll across landscapes or follow his characters across a stretch of terrain, they have a revitalizing effect on a more discerning viewer, particularly one not nourished by the relentless cuts of Hollywood cinema. The viewer experiences an exhilarating acknowledgment and identification of Mizoguchi’s bold mise-en-scène, how it informs a given scene, and how the long take engages our visual sense in a manner few other technical flourishes can.

In Ugetsu more than any other Mizoguchi film, Miyagawa uses extended crane shots to follow the characters within a landscape for a specific metaphoric purpose. These sequences unfold in a way directly related to medieval Japanese scroll paintings, while also containing an ethereal quality associated with suiboku-ga, paintings made in monochromatic ink (a method of painting developed in China and adopted by Buddhist monks). Traditional Japanese painting compositions placed tiny figures within monumental scroll and screen panoramas, flattening the depth of field so everything within the vista remained in focus. The act of unspooling the scroll of the scene represents a characteristic Mizoguchi metaphor. In the boat sequence on Lake Biwa, for example, the director captures entire scenes in long takes by pulling the camera along and observing from a distance. He resists close-ups and instead creates a broad picture of the characters in their environment. The viewer’s eyes follow as Mizoguchi extends the scroll or, for an alternative metaphor, walks along a Japanese screen with its individual wood panels angled along the floor. The effect creates a sense of omniscience, such as when the camera rises above Ugetsu’s characters to suggest their spiritual transmigration into another realm. Perhaps even more impressive than the Lake Biwa shot is a single transition that shows Genjuro, inside Lady Wakasa’s manor, and then moves outside, across the property to a bath, where Genjuro now sits with his enchantress, as though he has teleported through the ethereal plane.

Thematically, the director’s anti-war sentiments underscore Ugetsu, reflected by his use of human realism throughout the picture. Mizoguchi uses much of the film’s first-half to invest his audience in the peasant experience during wartime, undoubtedly drawing from his own experiences trying to survive during World War II. Modest huts and interior dwellings suddenly become prisons as soldiers pillage and rape their way across the landscape. Listen to the background noise in these scenes: Mizoguchi imbues scenes of devastation with barking dogs, distant screams, and the sound of scurrying people about the scene. Scenes in the aftermath prove just as intense and pitiless as the invading soldiers. A few brave peasants sneak back into their homes for food or, in Genjuro’s case, to check on his kiln. The nervous terror felt in these cautious scenes is chillingly realized. Straggling soldiers and bandits linger about the scene, taking advantage of the abandoned village. Or consider how Mizoguchi uses realism in a later sequence where Miyagi flees from soldiers, who proceed to rob her of her food and spear her to death. Mizoguchi’s omniscient camera follows her the whole way, and the shot pulls back to take a bird’s eye view, looking down as her assailants scurry across a rice field. Over the scene, the sound of Miyagi’s child crying reverberates and remains unresolved. Call it realism, naturalism, or mannered verisimilitude, Mizoguchi projects a grim and expertly rendered depiction of wartime ruin on everyday lives.

Thematically, the director’s anti-war sentiments underscore Ugetsu, reflected by his use of human realism throughout the picture. Mizoguchi uses much of the film’s first-half to invest his audience in the peasant experience during wartime, undoubtedly drawing from his own experiences trying to survive during World War II. Modest huts and interior dwellings suddenly become prisons as soldiers pillage and rape their way across the landscape. Listen to the background noise in these scenes: Mizoguchi imbues scenes of devastation with barking dogs, distant screams, and the sound of scurrying people about the scene. Scenes in the aftermath prove just as intense and pitiless as the invading soldiers. A few brave peasants sneak back into their homes for food or, in Genjuro’s case, to check on his kiln. The nervous terror felt in these cautious scenes is chillingly realized. Straggling soldiers and bandits linger about the scene, taking advantage of the abandoned village. Or consider how Mizoguchi uses realism in a later sequence where Miyagi flees from soldiers, who proceed to rob her of her food and spear her to death. Mizoguchi’s omniscient camera follows her the whole way, and the shot pulls back to take a bird’s eye view, looking down as her assailants scurry across a rice field. Over the scene, the sound of Miyagi’s child crying reverberates and remains unresolved. Call it realism, naturalism, or mannered verisimilitude, Mizoguchi projects a grim and expertly rendered depiction of wartime ruin on everyday lives.

Because Mizoguchi largely explored social and historical realism in his pictures, the presence of ghosts in Ugetsu marks an oddity in his works. The choice stems from his desire to explore formal and thematic elements from traditional noh theater in Ugetsu, and noh often involved tales of ghosts and maligned spirits. Typically in noh theater, a ghost is a framing device that recounts its story for the hero, explaining how it ended up a ghost to create a parallel to an event that has already occurred in the story or to foreshadow something yet to come. Unlike the blood-curdling ghosts of Hollywood, noh ghosts like Lady Wakasa seem alluring, mysterious, and seductive (as opposed to carnal and sexualized), while Miyagi seems gentle and loving. Mizoguchi’s treatment of the characters is a departure from Ueda’s source material, especially in the case of Lady Wakasa, as her terrifying serpent form from the book has no place in Ugetsu and its embrace of reserved noh traditions. Furthermore, Lady Wakasa appears in typical noh costume, her makeup reminiscent of a noh mask. When she dances for Genjuro, all of Mizoguchi’s aesthetic preoccupations converge, from the particular look of her kimono to the biwa music played her servant, and finally the movements of her dance to the traditional song. Everything onscreen with Lady Wakasa feels compelled by noh theater, while the sequence nevertheless feels perfectly integrated into the realistic world of the film.

More than just ghosts, Mizoguchi integrates noh music and set-pieces into his film. Composer Hayasaka Fumio wanted to use a Western score, but Mizoguchi insisted that Fumio use a noh flute, and the resulting score blends a traditional Japanese theater sound with more cinematic music. But the uses of these noh techniques also have a cultural significance that may be missed on Western viewers. Ugetsu contains no trace of the outside world, such as the Western influence on Kurosawa; rather, only Japanese painting, music, and theater have bearing here. The film’s most impressive and gorgeous sequences draw from noh and kaidan traditions. The haunting yet aching scenes with Lady Wakasa, a lonely ghost whose living status as a princess was not met with a lover before she died; having died alone, her spirit has returned to fulfill her desires. Cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa shot in low light to achieve her ghostly appearance. Mizoguchi wanted a very little contrast on the film stock to create similarities to suiboku-ga. However, Miyagawa’s soft lighting wasn’t faded enough to create the desired effect; he had to overdevelop the film several times to achieve an intentionally flat, washed-out appearance. The film’s aesthetics also reflect its themes in a mannered, deliberate way that carries notions of noh dramas and Buddhism through its uses of fog, mystery, and gradual movement within a scene.

Ugetsu’s movements between realistic scenes and the more other-worldly remain among the most transfixing in all of cinema. Mizoguchi effortlessly transitions between the real world of wartime death and survival to the eerie world of finer things, erotic joys, and the irresistible pleasures of the flesh—all achieved through his use of ambition as a theme, as well as ghosts. The balance between human drives and the spiritual springs more from Mizoguchi than Ueda’s source material. Ueda stories have been adapted for greater interconnectivity, but also greater consequence and artistic purpose. Rather than sensationalizing the original story by turning Lady Wakasa into a serpent in the finale through a mystical transformation, or even the appearance of a snake, the outcome proves entirely poetic. For instance, Ueda’s story contains none of the more seductive scenes between Genjuro and Lady Wakasa, all of which were created by Mizoguchi and his writers. Take when Lady Wakasa dances for Genjuro and hypnotizes him, and the scene serves as a sort of reverse snake charm; later, they bathe together and consummate their union. All of these moments were added by Mizoguchi to deepen the story’s emotional resonance, but also suggest the beleaguered state of women.

After all, Lady Wakasa’s fate echoes Miyagi’s, having been killed by soldiers during a raid on her family manor. Regardless of her deception, Lady Wakasa is a tragic figure in her solitude, loneliness, and desperation for affection—the absence of love and family that Miyagi could, for a time, enjoy. And though the sequences with Lady Wakasa draw the viewer’s attention due to their memorable supernatural elements, the character remains a supplementary inclusion to the film’s overriding theme that war leads to suffering, especially among women. Mizoguchi’s themes do not suggest cautionary tales for women or provide censures for men; they depict life as he sees it: Driven by ambitions and restless dreams, people force changes in their lives that cause suffering to others. But the director does not propose an alternative or suggest an impossible corrective action. Had Genjuro or Tobei insisted on staying home, their fates would undoubtedly be sealed by the larger scope of civil war. But the tragedy persists in how Tobei’s ambitions leave Ohama to suffer no end of indignities as a prostitute and rape victim. Miyagi’s husband disregards her in pursuit of his own greed, leaving her to become a wartime refugee and eventual victim of its violence. And yet, the women of Ugetsu forgive their husbands’ transgressions, redeeming them through their eventual return home.

Suffering is an innate part of life for women in Mizoguchi’s cinema, and in the world at large—that much has not changed since the time of this film’s release. Man’s drive for glory has dire costs for the women they leave behind, take for granted, or victimize, with consequences in Ugetsu that echo into the afterlife. Mizoguchi considers a woman’s fate to be the symbol of human cruelty, and his films emphasize the pattern of male ambition at a woman’s expense. Ugetsu is just one of several film he made at the height of his international renown in the 1950s, followed by The Life of Oharu (1952), Sansho the Bailiff (1954), and Street of Shame (1955), each of them about the suffering of women in roles from banished wives to those forced into geishadom. And while his other films reflect upon the ruin of women inflicted by their culture or social status in a historical setting, Ugetsu offers an outpouring of characteristically Japanese artforms integrated and reformatted for cinema. Mizoguchi’s treatment of traditional Japanese art combines with his humanist empathy, flush historical detail, and formal metaphors, giving Ugetsu its transportive power, and its harmony between the real and supernatural.

Bibliography:

Le Fanu, Mark. Mizoguchi and Japan. British Film Institute, 2005.

Lopate, Phillip. “Ugetsu: From the Other Shore.” Criterion.com. 7 Nov. 2005. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/401-ugetsu-from-the-other-shore. Accessed 13 June 2017.

Reider, Noriko T. “The Emergence of Kaidan-Shu: The Collection of Tales of the Strange and Mysterious in the Edo Period.” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 60, no. 1, 2001, pp. 79-99.

Sato, Tadao. Kenji Mizoguchi and the Art of Japanese Cinema. Berg, 2008.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review