The Definitives

Critical essays, histories, and appreciations of great films

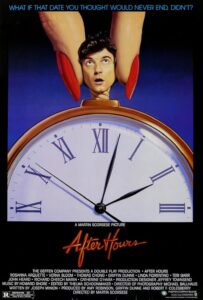

After Hours

- Director

- Martin Scorsese

- Cast

- Griffin Dunne, Rosanna Arquette, Verna Bloom, Linda Fiorentino, Teri Garr, John Heard, Catherine O'Hara, Dick Miller, Will Patton, Cheech Marin

- Rated

- R

- Runtime

- 97 min.

- Release Date

- 10/11/1985

Martin Scorsese’s After Hours exists in a fever dream, where strange people behave in even stranger ways, and an obsessive rationale inhabits every detail. To watch the comedy is to willingly submit yourself to a pattern of horrifying coincidences in which brief moments of security and possibility give way to confusing yet unsettling danger. “Kafkaesque” might be adequate to describe its paranoid internalism, except the term scarcely accounts for the unreservedly bizarre conduct on display or its richly comic effect. Then again, the film tangles the viewer into such unbearable knots that from scene to scene it may not feel like a comedy at all, but rather a twisted trip down the rabbit hole into a Wonderland-esque version of New York City, the likes of which only the director of such New York films as Mean Streets (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976) could represent. Scorsese’s 1985 release, though not commonly measured alongside his best works, represents a stylistic exercise unmatched in his career—an undertaking wherein the methods and sensations of the production are far more significant than the nightmare logic that makes them possible.

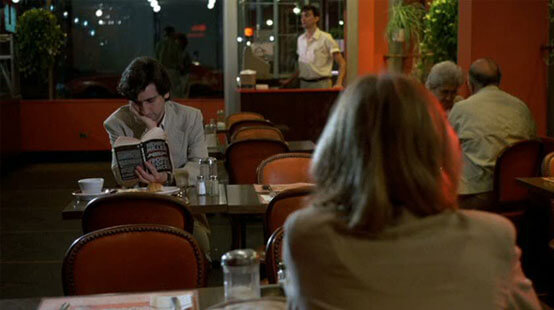

Lowly word processor Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne) needs to get out of his apartment one night to make a connection, so he heads to a diner and reads Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. As luck would have it, an attractive young woman named Marcy (Rosanna Arquette) notices him reading and strikes up a conversation about Miller. On the elusive promise of a casual sexual encounter, he’s enticed from his safe, midtown Manhattan comfort zone into the weird and wonderful goings on of SoHo after midnight, all on the thin pretense of buying a Plaster of Paris bagel-and-cream-cheese paperweight from Marcy’s artist friend, Kiki (Linda Fiorentino). But, as one character observes, it must be a full moon. Nothing works out for Paul. He loses his only $20 bill in the cab ride to Kiki’s loft, where Marcy is staying. Before long, Marcy’s cryptic behavior impels Paul to bolt for home, except subway fares have gone up, and he hasn’t enough change. Rain forces him into a nearby bar owned by Tom (John Heard), where Paul is promised subway fare if he can go to Tom’s apartment and pick up keys to a locked register. When Paul heads out, he’s sidetracked and drawn into another seemingly unconnected encounter. His night becomes a series of horrifying episodes that make us wonder, Can this night possibly get any worse? Of course it can, and it does. One thing happens after another, and a sense of peril, impossibility, and surreality fester beneath every encounter.

Without money or a ride home, Paul is reduced to accepting favors from the sorts of people who only come out after dark. And because he has no other choice, he’s forced to endure their strangeness just to get out of the rain or find a place to sleep. He’s tired and just wants to go home and, in some cases, do the right thing. But the night, or perhaps it’s the city, won’t let him. Take when Paul sees two burglars (Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong) walking off with one of Kiki’s human figure sculptures; being a Good Samaritan, he chases after them and resolves to return the piece. When he reenters Kiki’s loft, he discovers Marcy dead, having committed suicide presumably after he abandoned her. He returns to Tom’s bar, but the doors are locked; Tom is out looking for Paul who has his keys. Where can Paul stay except with Julie (Teri Garr), Tom’s flirty “Miss Beehive 1965” waitress who sketches portraits and keeps rat traps around her bed? Later, Paul is taken in by Gail (Catherine O’Hara), a short-tempered Mister Softee ice-cream truck driver with a morbid sense of humor. As Paul tries to remember a telephone number from directory assistance to call a friend for a ride, Gail prattles off numbers, laughing, making it impossible for him to remember the number he stubbornly refuses to write down.

Without money or a ride home, Paul is reduced to accepting favors from the sorts of people who only come out after dark. And because he has no other choice, he’s forced to endure their strangeness just to get out of the rain or find a place to sleep. He’s tired and just wants to go home and, in some cases, do the right thing. But the night, or perhaps it’s the city, won’t let him. Take when Paul sees two burglars (Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong) walking off with one of Kiki’s human figure sculptures; being a Good Samaritan, he chases after them and resolves to return the piece. When he reenters Kiki’s loft, he discovers Marcy dead, having committed suicide presumably after he abandoned her. He returns to Tom’s bar, but the doors are locked; Tom is out looking for Paul who has his keys. Where can Paul stay except with Julie (Teri Garr), Tom’s flirty “Miss Beehive 1965” waitress who sketches portraits and keeps rat traps around her bed? Later, Paul is taken in by Gail (Catherine O’Hara), a short-tempered Mister Softee ice-cream truck driver with a morbid sense of humor. As Paul tries to remember a telephone number from directory assistance to call a friend for a ride, Gail prattles off numbers, laughing, making it impossible for him to remember the number he stubbornly refuses to write down.

In a way, After Hours is a comic reflection of Scorsese’s Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, or even Bringing Out the Dead. Each film represents New York City as a fascinating, mythic haven for a peculiar cross-section of urban human strangeness unlike anywhere else on Earth. Taxi Driver revels in the city’s lowest point, when crime rates were frighteningly high and the streets raged with criminality and prostitution, and the frenzy gives birth to Travis Bickle’s psychosis. After the film, one feels afraid to step into a cab for fear of who might be driving. Bringing Out the Dead drops the viewer into a terrifying version of New York City saturated by derelicts, junkies, and ghosts on every corner. The film takes place in the 1990s during the manic late-night shifts suffered by Nicolas Cage’s ambulance driver, whose resolve against the city has long since been worn down and defeated. After Hours remains bemused by the bizarre human specimens that emerge in the city at night: A leather-clad sadomasochist named Horst (Will Patton); a Club Berlin bouncer (Clarence Felder) versed in Kafka; and a lonely artist named June (Vera Bloom) who seems to take motherly sympathy on Paul, until she imprisons him in a sculpture that resembles Edvard Munch’s The Scream. All of them seem as though they’re out to get Paul. For what reason, who knows?

The film is populated by characters that remain impossible to know or in some cases even understand, and this quality drives our predominant feeling of fearful paranoia about them. One character might seem normal until some unusual detail about them tears down our first impression. Consider Paul’s exchanges with Marcy, who’s either a pathological liar or just your garden-variety lunatic. Who can know for sure? Their first conversation in the diner begins with Henry Miller’s writing, and then Marcy scoots closer to point out the diner clerk who’s “a little weird.” And so, she seems normal enough, being able to identify the strangeness in others. Later, Marcy proceeds to talk about her first husband, how he’d shout “Surrender Dorothy!” when he climaxed in bed because he was obsessed with The Wizard of Oz. In her bedroom, Marcy tells Paul that she was raped once. “As a matter of fact it happened right here in this very room,” she explains. Paul looks about the bed aghast. “He came in through there on the fire escape. He held a knife to my throat and said if I made a move, he’d cut my tongue out. He tied me to the bed… He took his time… Six hours.” Paul is almost speechless. “Actually it was a boyfriend of mine,” she continues offhandedly. “To tell you the truth, I slept through most of it. So… there you are.” This is not the kind of story most people would end with “there you are.”

The film is populated by characters that remain impossible to know or in some cases even understand, and this quality drives our predominant feeling of fearful paranoia about them. One character might seem normal until some unusual detail about them tears down our first impression. Consider Paul’s exchanges with Marcy, who’s either a pathological liar or just your garden-variety lunatic. Who can know for sure? Their first conversation in the diner begins with Henry Miller’s writing, and then Marcy scoots closer to point out the diner clerk who’s “a little weird.” And so, she seems normal enough, being able to identify the strangeness in others. Later, Marcy proceeds to talk about her first husband, how he’d shout “Surrender Dorothy!” when he climaxed in bed because he was obsessed with The Wizard of Oz. In her bedroom, Marcy tells Paul that she was raped once. “As a matter of fact it happened right here in this very room,” she explains. Paul looks about the bed aghast. “He came in through there on the fire escape. He held a knife to my throat and said if I made a move, he’d cut my tongue out. He tied me to the bed… He took his time… Six hours.” Paul is almost speechless. “Actually it was a boyfriend of mine,” she continues offhandedly. “To tell you the truth, I slept through most of it. So… there you are.” This is not the kind of story most people would end with “there you are.”

Beyond Marcy’s mere strangeness, she’s something of an unsolved mystery. Or perhaps Paul is just imagining it all. When he first arrives at Kiki’s loft, Marcy isn’t there. She’s gone out to the all-night drug store for a prescription. Paul asks Kiki if Marcy is okay. “It’s under control,” she says. Kiki goes on to say that some people are covered with “horrible, ugly scars” from head to toe. “I’m just telling you now,” she adds. Soon Marcy returns from the drug store. She and Paul go into her bedroom. She showers, and when she’s gone Paul snoops in her bag, where she has a book on burn victims and ointment for second-degree burns in a pharmacy bag. She returns from the shower and sits down on the bed next to Paul. For a brief moment, he notices her bare leg and sees what appear to be gashes, maybe claw marks on her inner thigh. Is this what Kiki was referring to? What the hell happened to Marcy? And given the increasing number of oddities about her, how can Paul escape this impossible situation without offending her? Later in the film, when Paul returns to Kiki’s loft and finds Marcy dead, he cannot resist pulling the covers back to inspect her thigh. But there are no claw marks, only a tattoo of a skull in a top hat—the same image on Tom’s the bar owner’s keychain. The entire evening may be an unsolved mystery populated by curious late-nighters, but Paul too perpetuates the mystery in his own imagination.

Every encounter throughout Paul’s evening takes a turn like this, where his simple expectations for an individual go terribly wrong. Their behavior proves at times baffling; the world has turned upside-down. An all-consuming sense of helplessness prevails along with the feeling that the city and its late-night inhabitants are out to get him. When he goes into the punk haven Club Berlin to find Kiki and her boyfriend Horst to tell them about Marcy’s death, Paul narrowly escapes the club’s “Mohawk night” with just a chunk of hair buzzed off. Perhaps he’s being punished for following his rather low, lustful drive for casual sex with Marcy. Perhaps the city after hours is no place for anyone, much less a yuppie word processor looking for a meaningful or even casual connection. By the time he’s being chased through the city streets by a throng of neighborhood watch fanatics who are convinced he’s the burglar robbing their homes, the film has transformed from a comedy into an all-out paranoid hallucination. In one scene, Paul hides from a mob and in a nearby window notices a couple bickering; all at once the woman pulls a gun and shoots her husband dead. The horror of the random violence is offset by dark humor: “I’ll probably get blamed for that,” Paul remarks. There’s no safety cushion for him, and the viewer has no earthly idea how far these unhinged people could go. We’re even convinced our protagonist might die at some point.

Every encounter throughout Paul’s evening takes a turn like this, where his simple expectations for an individual go terribly wrong. Their behavior proves at times baffling; the world has turned upside-down. An all-consuming sense of helplessness prevails along with the feeling that the city and its late-night inhabitants are out to get him. When he goes into the punk haven Club Berlin to find Kiki and her boyfriend Horst to tell them about Marcy’s death, Paul narrowly escapes the club’s “Mohawk night” with just a chunk of hair buzzed off. Perhaps he’s being punished for following his rather low, lustful drive for casual sex with Marcy. Perhaps the city after hours is no place for anyone, much less a yuppie word processor looking for a meaningful or even casual connection. By the time he’s being chased through the city streets by a throng of neighborhood watch fanatics who are convinced he’s the burglar robbing their homes, the film has transformed from a comedy into an all-out paranoid hallucination. In one scene, Paul hides from a mob and in a nearby window notices a couple bickering; all at once the woman pulls a gun and shoots her husband dead. The horror of the random violence is offset by dark humor: “I’ll probably get blamed for that,” Paul remarks. There’s no safety cushion for him, and the viewer has no earthly idea how far these unhinged people could go. We’re even convinced our protagonist might die at some point.

But for Scorsese, the implacable Kafkaesque tone of After Hours took on a separate, personal meaning. As he tried to develop an adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’ book The Last Temptation of Christ, his string of failed attempts and Hollywood bureaucracy undoubtedly fueled After Hours’ potent mood of confusion, fear, and frustration. In 1983, Scorsese had just released The King of Comedy and went into production on The Last Temptation of Christ with Paramount Pictures. Over nine months of preparation, Scorsese and Jay Cocks rewrote and expanded Paul Schrader’s 90-page screenplay, began casting, and scouted locations in the Middle East. Paramount, reminded of Michael Cimino’s legendary bomb the previous year with Heaven’s Gate, was concerned that another high-profile director was getting out of control with a large budget and self-indulgent production. Moreover, religious fundamentalists wrote the studio and objected to the adaptation of Kazantzakis’ controversial text, while at the same time budgetary estimates continued to grow. Paramount at last canceled the production, saying, “It’s not worth the trouble”—this after Scorsese and his crew had already begun to build sets and make costumes. Everyone who said Scorsese’s picture was greenlit suddenly said his production would never happen. He couldn’t trust anyone, it seemed. Frustrated and eager to begin making another film as soon as possible, Scorsese was offered and passed on “hot” scripts for Beverly Hills Cop and Witness. He finally settled on Joe Minion’s After Hours, which the 26-year-old writer had completed for a course at Columbia University taught by Serbian director Dusan Makavejev (Sweet Movie, 1974). As Scorsese himself pointed out, Makavejev gave Minion’s script an “A” grade.

Originally called Lies and later A Night in SoHo, Minion’s script, owned by actors Amy Robinson and Griffin Dunne, could be shot fast and for cheap. Robinson and Dunne had already started to develop the project with a young Tim Burton as director, but when Scorsese showed interest, Burton willingly stepped aside. After everything that had just occurred with his Hollywood production of The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese was drawn to the prospect of a low-budget independent film on which he had creative control away from a major studio. He rewrote portions of the final script, but much of Minion’s original draft was, in fact, based on an uncredited monologue called “Lies” by radio artist Joe Frank. (Frank eventually filed a plagiarism suit and the matter was settled, kept quiet, and rarely acknowledged in subsequent years.) With a budget of $3.5 million, Scorsese was faced with the challenge of filming on location in New York City with a forty-day shooting schedule, something he hadn’t attempted since his younger days making Taxi Driver. “I thought it would be interesting to see if I could go back and do something in a very fast way,” Scorsese remembered. “All style. An exercise completely in style. And to show they hadn’t killed my spirit.” He was assigned a new cameraman, Michael Ballhaus, a frequent collaborator with German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder (The Marriage of Maria Braun, 1979). Under the prolific Fassbinder, Ballhaus had grown accustomed to speedy shoots with little money, and alongside Scorsese, he developed innovative camera movements, supported by then-new high-speed lenses.

Originally called Lies and later A Night in SoHo, Minion’s script, owned by actors Amy Robinson and Griffin Dunne, could be shot fast and for cheap. Robinson and Dunne had already started to develop the project with a young Tim Burton as director, but when Scorsese showed interest, Burton willingly stepped aside. After everything that had just occurred with his Hollywood production of The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese was drawn to the prospect of a low-budget independent film on which he had creative control away from a major studio. He rewrote portions of the final script, but much of Minion’s original draft was, in fact, based on an uncredited monologue called “Lies” by radio artist Joe Frank. (Frank eventually filed a plagiarism suit and the matter was settled, kept quiet, and rarely acknowledged in subsequent years.) With a budget of $3.5 million, Scorsese was faced with the challenge of filming on location in New York City with a forty-day shooting schedule, something he hadn’t attempted since his younger days making Taxi Driver. “I thought it would be interesting to see if I could go back and do something in a very fast way,” Scorsese remembered. “All style. An exercise completely in style. And to show they hadn’t killed my spirit.” He was assigned a new cameraman, Michael Ballhaus, a frequent collaborator with German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder (The Marriage of Maria Braun, 1979). Under the prolific Fassbinder, Ballhaus had grown accustomed to speedy shoots with little money, and alongside Scorsese, he developed innovative camera movements, supported by then-new high-speed lenses.

With limited resources and budgetary funds, Scorsese couldn’t afford to improvise; he planned out every shot in advance with small sketches and considered the editing long in advance. In this and other respects, Scorsese’s approach adopted a Hitchcockian style. Alfred Hitchcock was so famous for his meticulous pre-planning that it was often said that he didn’t need to be on-set, that his shots and editing had been worked out to such extreme detail in the storyboards and script, the day-to-day shoot was a just matter of completing what was already on paper. Of course, this was an exaggeration even for Hitchcock. Scorsese’s dependence on his storyboards required his flexibility when things inevitably went wrong during the tight shoot. In another way, Hitchcock inspired Scorsese’s visual approach in his concentration on simple objects throughout the film, fixating his frame on a thing to create the illusion of importance. Watch the way Scorsese uses close-ups of hands reaching for objects such as Kiki’s Plaster of Paris bagel, the elusive $20 bill, or a finger on a door buzzer. These objects have the same fascination as the shot of Norman Bates’ knife in Psycho, the close-up of the lighter in Strangers on a Train, or the Unica key in Notorious. Simple items are impregnated with incredible significance, and Scorsese uses this tactic to enhance Paul’s, and thus the viewer’s, irrational mistrust toward and obsession over everyone and everything around him.

Who could blame someone for not finding any of it very funny? It’s not inconceivable to imagine a moviegoer seeing Paul’s torturous Odyssey in SoHo as nothing more than an uncomfortable nightmare devoid of humor and full of tension, even suspense. But mixed feelings toward Scorsese’s films is not uncommon. All throughout the 1980s, Scorsese released films that were misunderstood. For example, The King of Comedy is a morbid picture about an aspiring entertainer who takes his idol hostage to arrange his big break, and it was originally perceived as too cynical and even creepy to be funny. Like that film, After Hours makes us laugh at its protagonist’s misfortunes, which are of such an extreme and claustrophobic nature that for some the effect may pass right by humor and translate into tension. After all, Paul almost never has a moment of comfort or ease. He’s always trying to escape one discomfited situation only to find himself in another, until all at once, the inconveniences and misfortunes of his night grow so intense that they change from social oddity into physical danger.

Who could blame someone for not finding any of it very funny? It’s not inconceivable to imagine a moviegoer seeing Paul’s torturous Odyssey in SoHo as nothing more than an uncomfortable nightmare devoid of humor and full of tension, even suspense. But mixed feelings toward Scorsese’s films is not uncommon. All throughout the 1980s, Scorsese released films that were misunderstood. For example, The King of Comedy is a morbid picture about an aspiring entertainer who takes his idol hostage to arrange his big break, and it was originally perceived as too cynical and even creepy to be funny. Like that film, After Hours makes us laugh at its protagonist’s misfortunes, which are of such an extreme and claustrophobic nature that for some the effect may pass right by humor and translate into tension. After all, Paul almost never has a moment of comfort or ease. He’s always trying to escape one discomfited situation only to find himself in another, until all at once, the inconveniences and misfortunes of his night grow so intense that they change from social oddity into physical danger.

When Gail takes him in, she notices a news clipping stuck to his arm with plaster. She reads it aloud, “A man was torn limb from limb by an irate mob last night in the fashionable SoHo area of Manhattan. Police are having trouble identifying the man because no form of I.D. was found in his shredded clothing and his entire face was pummeled completely beyond recognition.” Will this be Paul’s fate? Sometime after suspicious neighbors start to question him about the area’s string of burglaries, a vindictive Julie draws his portrait on a wanted poster. Gail sees this and calls on her neighborhood watch, and suddenly the film turns into a Wrong Man thriller by way of Hitchcock. Paul Hackett now aligns with Cary Grant in North by Northwest (1959) or Robert Cummings in Saboteur (1942), while Howard Shore’s winding, kaleidoscopic score heightens our fear with the tempo of a ticking clock. Scorsese also channels Fritz Lang’s M (1931) in scenes where Paul runs from the ruthless neighborhood watch mob, their flashlights peering into windows and down wet city streets after him.

When the film finally ends the way it does, for some the moment of irony may be too small a release to fully relieve the anxiety built up throughout the picture. Despite Scorsese’s Hitchcockian level of preparation, he and the producers agreed that Minion’s original ending was unsatisfactory. Minion’s version featured Paul going out to buy June some ice-cream and then returning to her basement, “And that was it,” Scorsese remarked. “I felt something was missing.” Minion proposed another ending that would play on the surreal elements present in the film: Paul would escape the neighborhood watch when June grows in size and he enters her womb; in an ode to 2001: A Space Odyssey, Paul would’ve been reborn naked onto the cold city street, and then he’d get up and run home to safety. The expressive idea was rejected, regardless of its surrealistic appeal. At the time, British filmmaker Michael Powell (who, along with Emeric Pressburger, made fantastical films like The Red Shoes and A Matter of Life and Death) had been seeing Scorsese’s editor Thelma Schoonmaker romantically (they married the next year). Powell screened the unfinished film alongside Scorsese’s father with an ending where Cheech and Chong simply drive into the distance with Paul encased in June’s sculpture in their van. Both Powell and Scorsese’s father agreed the current ending was not only dissatisfying but infuriating, given how the audience has suffered along with Paul through the course of the film. Powell suggested that Paul falls out of the van and, in a supremely Kafkaesque flourish, gets up and walks back into work to start another day. Scorsese showed an unfinished cut to filmmakers like Terry Gilliam and Steven Spielberg, and everyone agreed Paul should fall out of the van and return to work. With this ending, Scorsese returns the audience to the safe, albeit dull office of a word processor, and we’re thankful for it.

Scorsese completed the film four days over schedule and one million dollars over-budget; however, the production was still considered low-budget and the eventual box-office performance turned a profit. The director followed After Hours with several other projects that were less passion pieces and more director-for-hire jobs: The Color of Money (1986), the Oscar-winning sequel to Robert Rossen’s The Hustler (1961), starring Paul Newman; an episode of the Spielberg-produced TV show Amazing Stories called “Mirror, Mirror” (1986); and Michael Jackson’s music video “Bad” (1987). He considered each a test of his talent and versatility across various video mediums. Finally, in 1987, Universal Studios picked up Scorsese’s production of The Last Temptation of Christ, a film which survived commercially by its controversy. And while After Hours seldom earns mention as one of Scorsese’s best films (on lists consisting of Goodfellas, Raging Bull, Taxi Driver, Mean Streets, The Departed, etc.), the film is his most unabashed stylistic exercise—an achievement in what has been called “pure filmmaking.” Only from the catastrophic delays on The Last Temptation of Christ could After Hours have emerged, itself a reaction to Scorsese’s frustration, disappointment, and aggravation—his desperate need to shoot a film, and fast. He may have agreed to the project just to keep busy, but one cannot help but see that a kind of transference has taken place from the director to the screen, leaving it a monumentally personal exercise of expulsion.

To categorize After Hours as merely a dark comedy or an offbeat entry in Martin Scorsese’s career overlooks the film’s entrenched paranoid atmosphere and dismisses the director’s personal, desperate need to put as much into one film as he could muster after toiling on his canceled version of The Last Temptation of Christ. Though Scorsese didn’t form the story from its inception, never once does After Hours feel like impassionate or impersonal filmmaking; rather, quite the opposite. It plays as if Scorsese was purging himself. His raw and unfiltered frustrations spill out onto the screen through Paul’s endless suffering. What could be more personal? Scorsese’s orchestration of Paul’s increasingly punishing night translates into a draining, hilarious experience that’s also something of a wonder, as the director has incorporated every stylistic method in his arsenal to further enhance the narrative. Ballhaus’ ever-mobile camera glides and shotguns about each scene with delirious speed, Schoonmaker’s editing develops a persistent rhythm, while both the audience and Paul are left to wonder what just happened and why. But these are questions that will go unanswered in After Hours. And before long we’re no longer chasing answers but running away from them, desperate to escape to safety. Through its deceptively simple function and concentration on style, After Hours captures Scorsese’s root mastery of the cinematic medium like no other picture to his name.

Bibliography:

Christie, Ian; Thompson, David (edited by). Scorsese on Scorsese. Revised Edition. London: Faber, 2003.

Scorsese, Martin; Henry, Michael. A Personal Journey Through American Movies. New York: Hyperion, 1997.

The Wolf of Wall Street

The Wolf of Wall Street  Funny People

Funny People  Synecdoche, New York

Synecdoche, New York