The Definitives

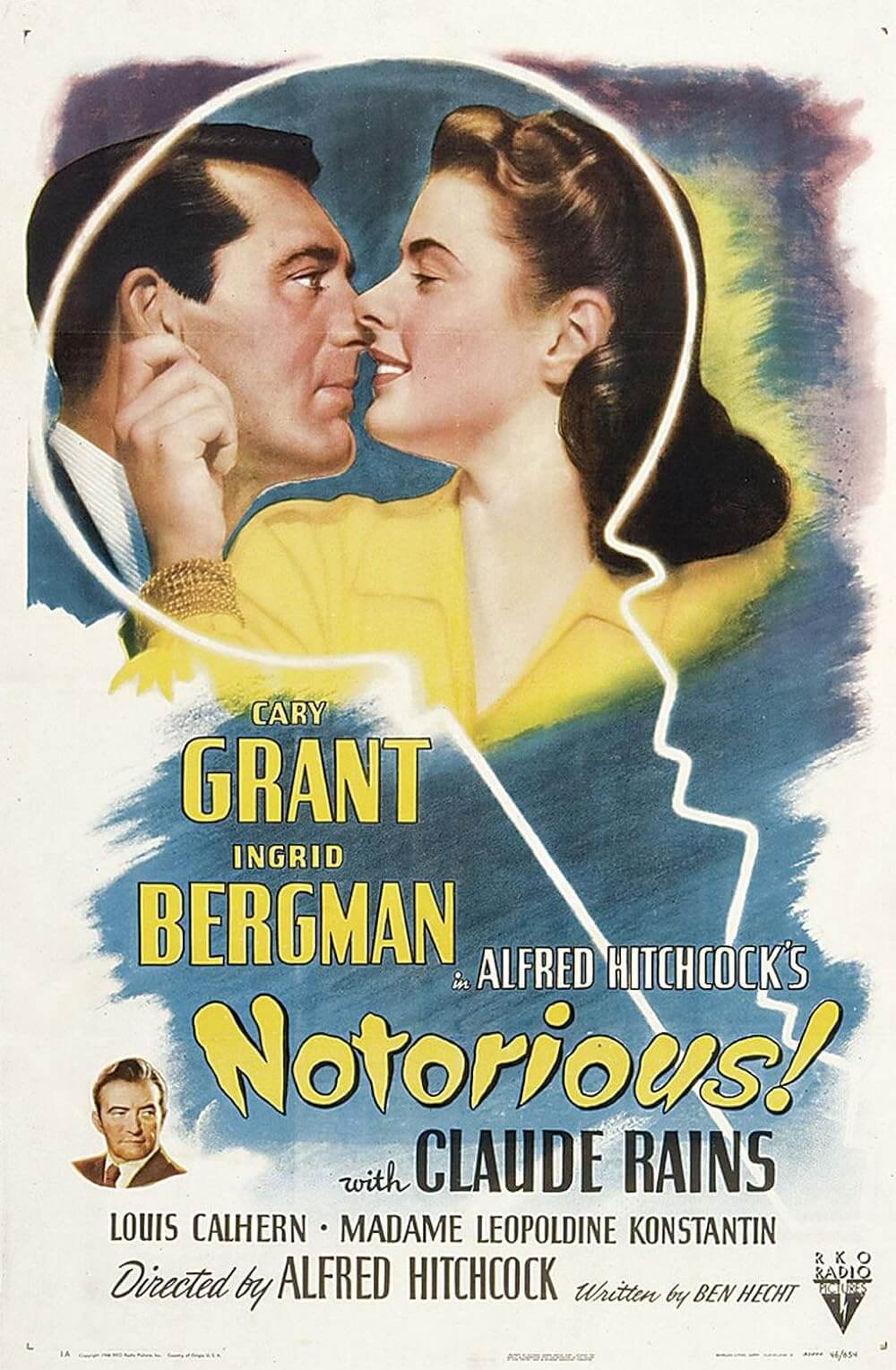

Notorious

Essay by Brian Eggert |

François Truffaut called Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious “the quintessential Hitchcock film,” as if there could be just one. Truffaut’s wise assessment in the face of Hitchcock’s preeminent Psycho or Vertigo demands investigation; after all, how strange that the quintessential film from the Master of Suspense is actually a complicated romance. Shrouded by a curtain of espionage, Hitchcock’s 1946 picture disguises itself behind a smokescreen of undercover spies, Nazi plots, and a pre-Atomic Age nuclear threat. Hitchcock’s numerous spy yarns, each filled with wrongly accused men and elaborate chases, were some of his most popular, but none of them achieve the balance between dramatic immersion and the director’s visual stylization at play in Notorious. This is a deceptive film wherein its composition works to define a quintessence to Hitchcockian storytelling, and yet at the same time, Hitchcock diverts from his archetypal narrative structures, gender assignments, and character functions to explore a scenario whose spy-thriller elements are never more important than the true, romantic intent. Ingenious for its marriage of breathless tension in an aching love story, it is Hitchcock’s greatest film.

The story surrounds Alicia Huberman, the daughter of a Nazi agent hiding in America just after WWII. Alicia is played by Ingrid Bergman, who had just finished filming Spellbound with Hitchcock the year before. Alicia is commissioned by T.R. Devlin (frequent Hitchcock collaborator Cary Grant), an agent who convinces her to go undercover in Rio de Janeiro where a consortium of Nazis plot their party’s return. Her specific purpose there is yet unknown to Devlin, only that her familial affiliation with the ousted party, which she has denounced, will help American interests. She agrees, and she and Devlin fly to Brazil where they ignite a brief but meaningful love affair. Devlin is eventually told Alicia’s mission: she is to bed Alexander Sebastian (Claude Rains), an undercover Nazi agent living surreptitiously in South America. Alicia’s well-known promiscuity and reputation as a party girl would seem to make her perfect for this Mata Hari assignment to discover what Sebastian and his group of Nazis are scheming. Ripped away from her newfound love, Devlin, she must pretend with and even marry another man in hopes of uncovering the Nazi secret.

The details of the Nazi secret, better known as a filmic contrivance or “MacGuffin”, is meaningless next to how the film’s setup tears at Alicia and Devlin. Hitchcock’s MacGuffin disguises the picture’s love story, making it about something other than love, when in actuality love is all there is, as they say. The MacGuffin is any film’s fabricated cause, utterly pointless in its specificity, but nonetheless, the reason everything happens. Hitchcock would often add the MacGuffin lastly to the script, as it was the film’s least important detail, despite all events revolving around it. His goal was to first imagine scenarios, and then afterward fit a MacGuffin that would allow those scenarios to progress naturally and to their full cinematic possibility. In Notorious, the MacGuffin is a wine bottle, specifically a 1934 Pommard filled with uranium, and through the search for this MacGuffin, Hitchcock’s romance drama blossoms. Replace the wine bottle with the frozen body of Hitler, a roll of microfilm, or any other thingamajig relatable to Nazis, and the plot would be the same—centered on the love triangle between Alicia and Devlin and Sebastian.

The details of the Nazi secret, better known as a filmic contrivance or “MacGuffin”, is meaningless next to how the film’s setup tears at Alicia and Devlin. Hitchcock’s MacGuffin disguises the picture’s love story, making it about something other than love, when in actuality love is all there is, as they say. The MacGuffin is any film’s fabricated cause, utterly pointless in its specificity, but nonetheless, the reason everything happens. Hitchcock would often add the MacGuffin lastly to the script, as it was the film’s least important detail, despite all events revolving around it. His goal was to first imagine scenarios, and then afterward fit a MacGuffin that would allow those scenarios to progress naturally and to their full cinematic possibility. In Notorious, the MacGuffin is a wine bottle, specifically a 1934 Pommard filled with uranium, and through the search for this MacGuffin, Hitchcock’s romance drama blossoms. Replace the wine bottle with the frozen body of Hitler, a roll of microfilm, or any other thingamajig relatable to Nazis, and the plot would be the same—centered on the love triangle between Alicia and Devlin and Sebastian.

But spy details are not the most interesting aspect about Notorious; rather, the games and suspense and romance denoted by it. Nevermind that the ore in Sebastian’s wine cellar could be used for an Atom Bomb. The audience does not care. Our concern resides in Alicia and Devlin’s eventual love, the suspense of stealing the wine cellar key, and their staying in character while in the presence of Nazis. The ‘34 Pommard allowed Hitchcock to conceive one of his most suspenseful setups, wherein Alicia steals Sebastian’s Unica-brand wine cellar key, slips Devilin into the cellar, where they uncover what the Nazis are planning. After her staged honeymoon, Alicia is told by Devlin to propose that Sebastian throw a party, so that she might meet Rio de Janeiro’s elite. Her first task requires taking the Unica key from Sebastian’s keychain. While he dresses in another room, she sneaks in to retrieve it. Just as she has the key, he enters, now dressed, and embraces his wife. Holding her endearingly on the forearm, Sebastian kisses the palm of her right hand; in her left hides the Unica key. Before he can kiss her left palm, she thrusts both arms around his neck—what might seem a desperate cuddle provides a narrow escape.

Cut to the night of the party, where a high crane shot gives us a full view of Sebastian’s massive foyer, and then tightens on Alicia standing nervously next to Sebastian; in the same move, the camera zooms to a detailed close-up of Alicia’s hand, where she hides the Unica key. This bravado shot is one of the most impressive of Hitchcock’s career, one of many in Notorious, and certainly complicated, requiring a number of shifting focuses, from wide-to-mid and mid-to-tight. Devlin, invited to the party, warns that their time is limited, as the butler is running low on serving wine and may have to enter the cellar soon; furthermore, Sebastian, jealous of the “very good looking” Devlin, is keeping an eye on his wife. Sneaking away, Alicia and Devlin enter the cellar to find the mysterious contents of the bottle. She keeps watch while he snoops. The sequence is intercut with shots back to the butler’s ice tub housing the party’s wine stock, creating writing suspense with an elegant countdown: first eleven bottles, then seven, then three. Back in the cellar, Devlin causes a bottle to slip from the shelf and break on the ground, spilling the uranium hidden inside. Quickly cleaning up, they replace the ore into an empty 1940 Pommard bottle, an inconsistency that Sebastian later notices, thus realizing Alicia is an American spy.

Cut to the night of the party, where a high crane shot gives us a full view of Sebastian’s massive foyer, and then tightens on Alicia standing nervously next to Sebastian; in the same move, the camera zooms to a detailed close-up of Alicia’s hand, where she hides the Unica key. This bravado shot is one of the most impressive of Hitchcock’s career, one of many in Notorious, and certainly complicated, requiring a number of shifting focuses, from wide-to-mid and mid-to-tight. Devlin, invited to the party, warns that their time is limited, as the butler is running low on serving wine and may have to enter the cellar soon; furthermore, Sebastian, jealous of the “very good looking” Devlin, is keeping an eye on his wife. Sneaking away, Alicia and Devlin enter the cellar to find the mysterious contents of the bottle. She keeps watch while he snoops. The sequence is intercut with shots back to the butler’s ice tub housing the party’s wine stock, creating writing suspense with an elegant countdown: first eleven bottles, then seven, then three. Back in the cellar, Devlin causes a bottle to slip from the shelf and break on the ground, spilling the uranium hidden inside. Quickly cleaning up, they replace the ore into an empty 1940 Pommard bottle, an inconsistency that Sebastian later notices, thus realizing Alicia is an American spy.

The central plot was inspired by John Taintor Foote’s story called “The Song of the Dragon”, published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1921. Foote’s yarn entailed a WWI-era theater producer smitten with an actress, who volunteers herself to seduce an enemy spy for a group of feds. Producer and Hollywood legend David O. Selznick became fascinated with “The Song of the Dragon” as early as 1939, envisioning Vivien Leigh as a potential star. Ingrid Bergman was later offered the role. At first, Bergman disproved of the story, believing a propaganda angle existed within its pages; but upon a second reading sometime later, the actress agreed with Selznick that it was a ripe part for any actress, specifically under Hitchcock. Selznick believed the material to be seasoned with Hitchcockian qualities, and Hitchcock agreed with Selznick on the story, but not his choice of actors. The producer wanted Joseph Cotten for Devlin, but Hitchcock cast Cary Grant in the lead role instead.

Starting in 1944, Hitchcock worked with writer Ben Hecht to rework Foote’s Mata Hari account into Notorious; not much else besides the basic plot of “The Song of the Dragon” survived the transfer. They updated the story by moving its events to WWII, afterward even, in spite of the war still raging as they worked. They conceived the uranium wine bottle plot device after a long period of deliberation. “A bomb is always good,” Hitchcock would say, as a plot detail or in this case a MacGuffin. It was strange that Hitchcock and Hecht knew the significance of uranium in 1944, one year before America dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Selznick had certainly never heard of it, and scoffed when it was pitched. Uranium seemed like an odd MacGuffin, and a risky one given the political climate of the period—not to mention that general audiences at the time would be unfamiliar with, therefore unresponsive to its onscreen suggestion. Hitchcock learned of uranium and the A-Bomb through Hollywood friends, a number of them serving as spies for the British Ministry of Information. It was not unheard of for everyday people, if not minor celebrities (such as actor Reginald Gardiner), to be asked to seduce enemy operatives for information. Everyone wants to talk to a movie star, even spies. Trade secrets were communicated by a few good loose-lipped men.

Starting in 1944, Hitchcock worked with writer Ben Hecht to rework Foote’s Mata Hari account into Notorious; not much else besides the basic plot of “The Song of the Dragon” survived the transfer. They updated the story by moving its events to WWII, afterward even, in spite of the war still raging as they worked. They conceived the uranium wine bottle plot device after a long period of deliberation. “A bomb is always good,” Hitchcock would say, as a plot detail or in this case a MacGuffin. It was strange that Hitchcock and Hecht knew the significance of uranium in 1944, one year before America dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Selznick had certainly never heard of it, and scoffed when it was pitched. Uranium seemed like an odd MacGuffin, and a risky one given the political climate of the period—not to mention that general audiences at the time would be unfamiliar with, therefore unresponsive to its onscreen suggestion. Hitchcock learned of uranium and the A-Bomb through Hollywood friends, a number of them serving as spies for the British Ministry of Information. It was not unheard of for everyday people, if not minor celebrities (such as actor Reginald Gardiner), to be asked to seduce enemy operatives for information. Everyone wants to talk to a movie star, even spies. Trade secrets were communicated by a few good loose-lipped men.

For scientific details, Hitchcock and Hecht visited Nobel Prize winner Dr. Robert A. Millikan at the California Institute of Technology, though this meeting was very hush-hush and undocumented, making it nearly impossible to verify. In later interviews, Hitchcock referred to his chat with Dr. Millikan, giving historians some indication that he indeed researched his MacGuffin well. The director would later claim that the FBI kept an eye on him for three months subsequently, hearing of Hitchcock’s interest in a subject no one was yet supposed to know about. Nevertheless, Hitchcock and Hecht insisted on their idea. More than half a year was spent on writing, working out plot details, and pinning down what, exactly, this film’s MacGuffin would be. Selznick, though adverse to the uranium idea, had better things to worry about—other over-budget projects he was more invested in and had further control over, such as Duel in the Sun. Two sides developed, as was often the case on Selznick productions: Selznick, representing the studio brass disconnected from artistic vision, and a massive creative half fronted by Hitchcock, Hecht, Bergman and Grant. Selznick was all but turned on his head when, after a budgetary argument, he threatened to sell the whole production to Hal B. Wallis at Warner Bros., and found that everyone on the creative end seemed pleased with the idea. It was a moot threat, however; Wallis rejected Notorious on the basis that the uranium was an unproven MacGuffin.

Never quite pleased with Hitchcock’s MacGuffin or the writers’ “contemporary” plot, Selznick sold the entire kit and caboodle to RKO producer William Dozier for a hefty $800,000. The producer would still retain fifty percent of all profits, but Hitchcock demanded that Selznick have no creative say on their production while at RKO. Though there was still occasionally one of Selznick’s infamous memos attempting to change some minor detail here or there, the contract with RKO allowed Hitchcock and Hecht to freely construct their Notorious vision without having to humor Selznick by pretending to consider his off ideas. Filming began in October of 1945, after more than a year of groundwork, and it was completed in January of 1946. Hitchcock and Hecht continued to rework the script while shooting, in sequence as the director often did, finishing pages sometimes the night prior to filming. Herein dwells an alternative to the customary Hitchcock preparation myth. Traditionally, Hitchcock was thought to have storyboarded every shot and work solely from script direction, which would be perfected in his laborious writing and storyboarding processes during pre-production. With Notorious, Hitchcock not only proves this myth false but shows how well he improvises without notes there in front of him. The director essentially produced Notorious under RKO, with Selznick contractually powerless on or off the set. His usual, legendary system of detailed preparation came about after working with Selznick and other dictatorial producers, as perfecting such early groundwork left no loose ends for a nosy producer to tamper with.

Never quite pleased with Hitchcock’s MacGuffin or the writers’ “contemporary” plot, Selznick sold the entire kit and caboodle to RKO producer William Dozier for a hefty $800,000. The producer would still retain fifty percent of all profits, but Hitchcock demanded that Selznick have no creative say on their production while at RKO. Though there was still occasionally one of Selznick’s infamous memos attempting to change some minor detail here or there, the contract with RKO allowed Hitchcock and Hecht to freely construct their Notorious vision without having to humor Selznick by pretending to consider his off ideas. Filming began in October of 1945, after more than a year of groundwork, and it was completed in January of 1946. Hitchcock and Hecht continued to rework the script while shooting, in sequence as the director often did, finishing pages sometimes the night prior to filming. Herein dwells an alternative to the customary Hitchcock preparation myth. Traditionally, Hitchcock was thought to have storyboarded every shot and work solely from script direction, which would be perfected in his laborious writing and storyboarding processes during pre-production. With Notorious, Hitchcock not only proves this myth false but shows how well he improvises without notes there in front of him. The director essentially produced Notorious under RKO, with Selznick contractually powerless on or off the set. His usual, legendary system of detailed preparation came about after working with Selznick and other dictatorial producers, as perfecting such early groundwork left no loose ends for a nosy producer to tamper with.

Notorious skews Hitchcockian convention with its characters as well, reversing Alicia and Devlin’s gender roles—roles that in Hitchcock’s oeuvre usually have tightly bound designations. Hitchcock’s obsessions repeated a frequent need to place the lead female, usually a blonde, virginal but certainly sexually attractive, in precarious situations, demanding that she be rescued by a heroic male. This male character is often an ordinary or “Wrong Man” thrown into an impossible set of circumstances. And yet, in Notorious, few of those all-too-frequent Hitchcockian stereotypes exist. Rather than a blonde ideal present merely to be rescued, Ingrid Bergman is a brunette, sexually experienced, even a drunk. Like many Hitchcock women, Alicia eventually needs to be rescued, yet only because she has thrust herself into a waning suicidal position. Devlin, meanwhile, is not Cary Grant’s Roger O. Thornhill from North by Northwest nor even the sly cat burglar John Robie from To Catch a Thief —he’s not a likable, good-humored everyman. Devlin is a spiteful character, sarcastic and sour toward Alicia; he loves her, but hates himself for loving her, thus derides her for his own self-loathing.

The night following her father’s trial, we see Alicia dressed in a risqué faux zebra-print midriff outfit (by costume designing legend Edith Head), partying with drunken friends. She finds Devlin there, and though he says nothing, she says she likes him. Feminist writer Tania Modleski argues in her book The Women Who Knew Too Much that Alicia’s role is strangely both a female object subjected to sexual investigation (a Hitchcockian ideal), and more significantly a sexual investigator. An interesting duality—even though Alicia is an object, it is she who leads the story. She demands the voyeur’s gaze, and yet she has clearly tamed her own sexuality enough to explore. Hitchcock wants us to adore our hero, but also experience the film through her eyes, so his camera illustrates Alicia’s duality. Third party camera positions place us in a spectator role. At the post-trial party, we first see only Devlin’s back; at the party, he’s observer watching Alicia pour drinks and act a fool (in a charming way, of course). In contrast, several point-of-view shots occur and work to identify the audience with Alicia. The morning after meeting Devlin, Alicia wakes, hung over, catching him in her bedroom’s doorway; when he approaches, the camera twists as she turns in her bed, rolling until the audience gets an upside-down view of Cary Grant.

The night following her father’s trial, we see Alicia dressed in a risqué faux zebra-print midriff outfit (by costume designing legend Edith Head), partying with drunken friends. She finds Devlin there, and though he says nothing, she says she likes him. Feminist writer Tania Modleski argues in her book The Women Who Knew Too Much that Alicia’s role is strangely both a female object subjected to sexual investigation (a Hitchcockian ideal), and more significantly a sexual investigator. An interesting duality—even though Alicia is an object, it is she who leads the story. She demands the voyeur’s gaze, and yet she has clearly tamed her own sexuality enough to explore. Hitchcock wants us to adore our hero, but also experience the film through her eyes, so his camera illustrates Alicia’s duality. Third party camera positions place us in a spectator role. At the post-trial party, we first see only Devlin’s back; at the party, he’s observer watching Alicia pour drinks and act a fool (in a charming way, of course). In contrast, several point-of-view shots occur and work to identify the audience with Alicia. The morning after meeting Devlin, Alicia wakes, hung over, catching him in her bedroom’s doorway; when he approaches, the camera twists as she turns in her bed, rolling until the audience gets an upside-down view of Cary Grant.

Joseph I. Breen, the chief enforcer of the Production Code, scoffed at an early draft of the screenplay for Notorious in 1945, finding Alicia “grossly immoral” and “superficially” a prostitute. A more Freudian explanation to her behavior resides in her feelings toward her Nazi father: she explains, “When I found out about him, I just went to pot. I didn’t care what happened to me.” She loves her father but despises him, torn between her family commitment and her opposition toward Nazism, just as we are torn between Alicia’s amorality and her clear hold over us as a protagonist. For that, her self-punishment extends far, to where she nearly allows herself to be poisoned, the same manner of death as her father. When Sebastian discovers his wife is a spy after the key incident, he goes to his mother, played by actress Leopoldine Konstantin. They develop a plan to slowly poison Alicia. Killing her quickly would draw attention from Sebastian’s Nazi cohorts, and to confess that he has married an American agent would mean his own death. Poison is the only way to keep her secret his. Alicia, pained with guilt and loving hatred for Devlin, keeps her poisoning a secret. When she and Devlin meet for one of their intermittent reporting sessions, she pretends to be hungover, hiding that she is sick. Perhaps she has resolved that without love, suicide, the same escape as her father, is her only solution, and so she resigns herself to inaction, thus accepting her death with suicidal extreme.

Hitchcock gives his audience no choice but to identify with Alicia, whose self-destructive behavior surfaces in heavy drinking. Alicia is not unlike Laraine Day’s Carol Fisher in Hitchcock’s 1940 film Foreign Correspondent—a woman pinched by her morality to do good after discovering her father is an enemy agent. Ironically, Alicia beds a Nazi to clear her guilty conscience brought about by her Nazi father. Victimized by her love for Devlin, all of the film’s pains and conflicts for the viewer reside in her, with Devlin as the distant spectator, out of the action but overseeing and judging, if not administering a kind of shock cure for Alicia’s guilt. Analogous to placing a child’s hand on a hot burner to teach it not to touch such things, Devlin thrusts Alicia into the film’s conflict, nearly killing her to prove what guilt-driven promiscuity and reckless behavior get you. Indeed, this is not the charming Cary Grant of His Girl Friday and Charade. Grant plays a character that would anticipate similar types that reflected the director’s obsessions with and manipulation of women in Vertigo, The Birds, Marnie, and other films. To this point in Hitchcock’s career, the director did not yet have an onscreen counterpart who shaped a woman according to a grand design as Devlin does. Devlin, through his backhanded way of forcing Alicia into service and then punishing her for it, corresponds to Hitchcock’s frequent method later in his career of shaping his leading ladies to conform to his vision. In doing so, Devlin is motivated by duty, but more so love and his inability to express it; he is drawn to Alicia’s sexuality, but he also resents her for her openness. “I’ve always been scared of women,” Devlin says. In this sense, Devlin is the epitome of Hitchcock, who in life practiced an almost celibate and reserved quality, whereas he explored the depths of his sexual fantasies in his films.

Hitchcock gives his audience no choice but to identify with Alicia, whose self-destructive behavior surfaces in heavy drinking. Alicia is not unlike Laraine Day’s Carol Fisher in Hitchcock’s 1940 film Foreign Correspondent—a woman pinched by her morality to do good after discovering her father is an enemy agent. Ironically, Alicia beds a Nazi to clear her guilty conscience brought about by her Nazi father. Victimized by her love for Devlin, all of the film’s pains and conflicts for the viewer reside in her, with Devlin as the distant spectator, out of the action but overseeing and judging, if not administering a kind of shock cure for Alicia’s guilt. Analogous to placing a child’s hand on a hot burner to teach it not to touch such things, Devlin thrusts Alicia into the film’s conflict, nearly killing her to prove what guilt-driven promiscuity and reckless behavior get you. Indeed, this is not the charming Cary Grant of His Girl Friday and Charade. Grant plays a character that would anticipate similar types that reflected the director’s obsessions with and manipulation of women in Vertigo, The Birds, Marnie, and other films. To this point in Hitchcock’s career, the director did not yet have an onscreen counterpart who shaped a woman according to a grand design as Devlin does. Devlin, through his backhanded way of forcing Alicia into service and then punishing her for it, corresponds to Hitchcock’s frequent method later in his career of shaping his leading ladies to conform to his vision. In doing so, Devlin is motivated by duty, but more so love and his inability to express it; he is drawn to Alicia’s sexuality, but he also resents her for her openness. “I’ve always been scared of women,” Devlin says. In this sense, Devlin is the epitome of Hitchcock, who in life practiced an almost celibate and reserved quality, whereas he explored the depths of his sexual fantasies in his films.

The centerpiece of Notorious is Alicia and Devlin’s broken romance. After they meet, Alicia confesses to Devlin, “I don’t like gentlemen who grin at me.” How true, since her bitter enemy, Sebastian, is a gentleman, while Devlin, her love, is anything but. Devlin is as his devilish name suggests: cruel and punishing toward Alicia for her willingness to participate in a Mata Hari plot against Sebastian. While at first her behavior is shocking to Devlin, he does not mind, insomuch that he falls in love with her. Love would seem to wash away her promiscuous reputation, giving her a new start. When he tests her upon first divulging what her role in Brazil is to be, he tells her to decide and refuses to decide for her. She chooses duty, unaware that Devlin is testing her to prove her confessed love for him. After this betrayal from Devlin’s point of view, he never misses an opportunity to scorn her. And when she tries to explain her motivations, she receives a customary response: “Skip it.” Indeed, their relationship throughout the film, until its harrowing climax, consists of two heartbroken lovers attempting to hurt the other through indirect action. Devlin behaves as if he were aware of what his role in a Hitchcock film should be, but resists that role—he derides Alicia with resentment, all but calling her a tramp on numerous occasions. That masochistic type of punishment goes both ways. Alicia may not be able to place Devlin into a Mata Hari situation akin to where he has placed her, but she tortures him as a spectator. She refuses to make it easy on him, twisting the knife whenever she can initially, to drive him mad with guilt for putting her in such a spot. Alicia gloats to Devlin “You can add Sebastian to my list of playmates.”

But this is also a love triangle, the third member being Sebastian, who Rains plays as gallant and kind, like a daring hero, whereas Devlin is more cowardly, if not villainous. Furthermore, Devlin will not stand up and fight for Alicia, to prevent her impending position under Sebastian, and she despises him for it. Instead, Grant plays an almost spineless character, trite and angry, working in the shadows. Sebastian, in contrast, is forthright, even polite and direct in his actions. Only Claude Rains could make a movie Nazi somehow sympathetic and charming. These temporary stations held by either character are later switched, of course, when Devlin makes his final dashing rescue of Alicia from the Nazi home, with Sebastian quiet, resigned to accept his doomed fate. Sebastian is also a distinct Hitchcock type, reminiscent of the later Norman Bates from Psycho, who, like Hitchcock himself, was a devoted mama’s boy. Hitchcock lived with his mother until his late twenties and depended on her like a safety blanket for much of his life. It cannot be ignored that Sebastian, when confronted with two major decisions in the film, marrying Alicia and eventually killing her, seeks counsel in his mother’s bedroom.

But this is also a love triangle, the third member being Sebastian, who Rains plays as gallant and kind, like a daring hero, whereas Devlin is more cowardly, if not villainous. Furthermore, Devlin will not stand up and fight for Alicia, to prevent her impending position under Sebastian, and she despises him for it. Instead, Grant plays an almost spineless character, trite and angry, working in the shadows. Sebastian, in contrast, is forthright, even polite and direct in his actions. Only Claude Rains could make a movie Nazi somehow sympathetic and charming. These temporary stations held by either character are later switched, of course, when Devlin makes his final dashing rescue of Alicia from the Nazi home, with Sebastian quiet, resigned to accept his doomed fate. Sebastian is also a distinct Hitchcock type, reminiscent of the later Norman Bates from Psycho, who, like Hitchcock himself, was a devoted mama’s boy. Hitchcock lived with his mother until his late twenties and depended on her like a safety blanket for much of his life. It cannot be ignored that Sebastian, when confronted with two major decisions in the film, marrying Alicia and eventually killing her, seeks counsel in his mother’s bedroom.

The final scenes play out in true Hitchcock fashion, with silence punctuating suspense. Having learned of Alicia’s illness, blown cover, and poisoning, Devlin arrives at Sebastian’s and races up the stairs for his first truly active participation thus far. Sebastian and his mother are powerless to stop him; should they attempt anything, they would give up to their Nazi guests that their syndicate has been penetrated by an American mole, allowed entry via Sebastian’s heart. If they accept that guilt, it would be a death sentence. Devlin bravely walks downstairs toward a Nazi greeting party with Alicia in his arms, the frightened Sebastian and his mother leading them as they fear their imminent deaths. Nazi goons standby, watching the scene, finding holes in Sebastian’s explanation that Alicia is off to the hospital. Devlin puts Alicia in his car and Sebastian follows in a moment of cowardice, begging Devlin to open the door, to save him from his Nazi partners. But Devlin has locked it, forcing Sebastian to accept his demise. Other possible endings were conceived, none with the minimalist wonder present in the final film. Of the suggestions, a bloody shootout was recommended, as well as a number of light postscript scenes that, with humor, might have lifted the audience away from Sebastian’s dreadful end. Hitchcock refused any alternatives.

As is, the last scene in Notorious is perfect, comparable to final shots in Casablanca or The Third Man. Truffaut called the film “precise as an animated cartoon,” and goes on to say the film has “a maximum of stylization and a maximum of simplicity.” Certainly, this ending attests to Truffaut’s statement. Our lovers drive off and Sebastian turns to walk up the stairs, back into his home where his Nazi partners will surely learn everything. A grim light from inside penetrates the night, with Sebastian’s shadow hanging behind him, as if Death follows him inside. Hitchcock believed in not pulling his punches, letting the suspense strike in pangs throughout the film until the climax, at which point the film would end with haste. Look at the finale of Saboteur, where his audience follows a Wrong Man escaping authorities, seeking out the person who framed him, catching the true saboteur, and in the last scene watching the villain slip off the Statue of Liberty (in no way a subtle political image). Despite some romance in the film, thus potential for falling action after this zenith (perhaps a scene where hero Robert Cummings embraces Priscilla Lane one last time, or even an apology from the authorities for wrongfully arresting him), Hitchcock ends Saboteur with the enemy falling to his death, closing the film in that very shot. The audience is left shocked. Hitchcock wants to sustain that feeling, prolong it as long as possible. He does not wipe it away, putting the audience at ease just in time for us to feel safe again as the credits roll, when we go back into the real world. For this reason, a Hitchcock ending often seems abrupt. His movies are never about the destination; they are about the journey there. Once you have arrived, there is no more story to tell.

As is, the last scene in Notorious is perfect, comparable to final shots in Casablanca or The Third Man. Truffaut called the film “precise as an animated cartoon,” and goes on to say the film has “a maximum of stylization and a maximum of simplicity.” Certainly, this ending attests to Truffaut’s statement. Our lovers drive off and Sebastian turns to walk up the stairs, back into his home where his Nazi partners will surely learn everything. A grim light from inside penetrates the night, with Sebastian’s shadow hanging behind him, as if Death follows him inside. Hitchcock believed in not pulling his punches, letting the suspense strike in pangs throughout the film until the climax, at which point the film would end with haste. Look at the finale of Saboteur, where his audience follows a Wrong Man escaping authorities, seeking out the person who framed him, catching the true saboteur, and in the last scene watching the villain slip off the Statue of Liberty (in no way a subtle political image). Despite some romance in the film, thus potential for falling action after this zenith (perhaps a scene where hero Robert Cummings embraces Priscilla Lane one last time, or even an apology from the authorities for wrongfully arresting him), Hitchcock ends Saboteur with the enemy falling to his death, closing the film in that very shot. The audience is left shocked. Hitchcock wants to sustain that feeling, prolong it as long as possible. He does not wipe it away, putting the audience at ease just in time for us to feel safe again as the credits roll, when we go back into the real world. For this reason, a Hitchcock ending often seems abrupt. His movies are never about the destination; they are about the journey there. Once you have arrived, there is no more story to tell.

Throughout Notorious, Hitchcock builds to his concise final moments by heightening the emotional resonance between Alicia and Devlin, and their inability to embrace one another. Consider the scene where Alicia reports to a room of American spies that Sebastian wants to marry her. Hitchcock almost exclusively shoots Alicia and Devlin, though they barely speak. As spy bosses ramble on about their plans, Hitchcock shows us that the two are in love. The American chief, Prescott (Louis Calhern), talks of the opportunity to gain important intel, but Hitchcock avoids keeping the camera on him—in its place, we see the agony on Bergman’s face, frustration in Grant’s. Prescott notices their glances and expressions throughout the picture; we suspect he knows they are in love, as certainly their inner romantic woes cannot be concealed.

While the film’s espionage thread offers the daring key sequence to punctuate it, Hitchcock concocts a likewise audacious scene for the couple’s love story. The director filmed what was then claimed to be “the longest kiss in film history” by condensing five pages of dialogue into one shot, extending not one kiss, but several small kisses over a prolonged period. The Production Code demanded that screen kisses not last more than three seconds; as is, Hitchcock has upwards of fifteen kisses (depending on your definition of a kiss), each broken up into smaller nibbles that append into one enormous bite. The kissing scene takes place before Devlin is told what Alicia’s role in Brazil will be, during their brief affair in Rio de Janeiro. Hitchcock wanted the conversation as natural as possible; he demanded that Bergman and Grant improvise their lines, avoid showiness or flair, and instead express an unsophisticated romantic moment. That is not to say the scene is simple: Grant and Bergman were horribly uncomfortable while filming the scene, keeping as intimately, unnaturally close together as Hitchcock demanded they be. What works on camera often does not in reality.

While the film’s espionage thread offers the daring key sequence to punctuate it, Hitchcock concocts a likewise audacious scene for the couple’s love story. The director filmed what was then claimed to be “the longest kiss in film history” by condensing five pages of dialogue into one shot, extending not one kiss, but several small kisses over a prolonged period. The Production Code demanded that screen kisses not last more than three seconds; as is, Hitchcock has upwards of fifteen kisses (depending on your definition of a kiss), each broken up into smaller nibbles that append into one enormous bite. The kissing scene takes place before Devlin is told what Alicia’s role in Brazil will be, during their brief affair in Rio de Janeiro. Hitchcock wanted the conversation as natural as possible; he demanded that Bergman and Grant improvise their lines, avoid showiness or flair, and instead express an unsophisticated romantic moment. That is not to say the scene is simple: Grant and Bergman were horribly uncomfortable while filming the scene, keeping as intimately, unnaturally close together as Hitchcock demanded they be. What works on camera often does not in reality.

This scene shows characters wrapped in each others’ arms, moving from the terrace indoors, Devlin answering a phone call from Prescott, and then moving to the door where Devlin slips out—all the while, Bergman and Grant are never more than a few millimeters away from each other. Rather than play the scene thick with sexual innuendo, as we would later see in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (in a familiar sequence between Grant and Eva Marie Saint), the two talk of their dinner, that Alicia will prepare chicken and Devlin will pick up champagne. Hitchcock famously told Truffaut that he hoped to include the audience in a “temporary ménage à trois” with the stars—a rare, if not odd filmic feature, indeed. But several ménage à trois scenes would appear throughout Hitchcock’s filmography, inviting the viewer to take part in the onscreen intimacy between two stars. He also claimed the scene was inspired by something he witnessed while in France, in a small town called Etaples: Two lovers stood against a wall. The boy urinated, and the girl held his hand while she casually looked around. That unshakable proximity, to Hitchcock, spelled true love.

Alicia Huberman and T.R. Devlin stand out in Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant’s careers, just as they do in Hitchcock’s methodology. Prior to Notorious, Bergman had played model women, damsels, even a nun, in movies like Casablanca, Gaslight, and The Bells of St. Mary’s. Grant’s name was best associated with Howard Hawks’ screwball comedies, an image he hoped to change. In 1941, Grant and Hitchcock attempted such a transformation of onscreen persona with Suspicion, a film that should have ended with Grant as a would-be wife-killer. Grant’s hopes to finally be depicted as a debased mind were squashed by cowardly studio execs unwilling to show the one-and-only Cary Grant as a potential murderer. Therefore, Suspicion ends with his wife (Joan Fontaine) realizing she has exaggerated her doubts in a severely anticlimactic finale, that it was all just a case of female hysterics (a sexist note to be sure). With Notorious, both performers would play against their respective, predestined Hollywood fronts, offering audiences an unexpected dynamic of character in either case, though neither is underlined as utterly wicked. Hollywood personas notwithstanding, Bergman and Grant were Hitchcockian ideals, particularly Grant as the director’s prototypical male lead. His suave good looks, onscreen charisma, ability to deliver fast-paced dialogue, and agile physical stature all appealed to Hitchcock, not to mention a few million moviegoers. During a number of his later productions, the director sought out Grant for his lead, accomplishing this task on only the three aforementioned occasions (frequently due to Grant’s busy schedule or high price tag). Few of Hitchcock’s leading men compare. James Stewart, Hitchcock’s recurrent voyeur, exists as Grant’s only competition.

Alicia Huberman and T.R. Devlin stand out in Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant’s careers, just as they do in Hitchcock’s methodology. Prior to Notorious, Bergman had played model women, damsels, even a nun, in movies like Casablanca, Gaslight, and The Bells of St. Mary’s. Grant’s name was best associated with Howard Hawks’ screwball comedies, an image he hoped to change. In 1941, Grant and Hitchcock attempted such a transformation of onscreen persona with Suspicion, a film that should have ended with Grant as a would-be wife-killer. Grant’s hopes to finally be depicted as a debased mind were squashed by cowardly studio execs unwilling to show the one-and-only Cary Grant as a potential murderer. Therefore, Suspicion ends with his wife (Joan Fontaine) realizing she has exaggerated her doubts in a severely anticlimactic finale, that it was all just a case of female hysterics (a sexist note to be sure). With Notorious, both performers would play against their respective, predestined Hollywood fronts, offering audiences an unexpected dynamic of character in either case, though neither is underlined as utterly wicked. Hollywood personas notwithstanding, Bergman and Grant were Hitchcockian ideals, particularly Grant as the director’s prototypical male lead. His suave good looks, onscreen charisma, ability to deliver fast-paced dialogue, and agile physical stature all appealed to Hitchcock, not to mention a few million moviegoers. During a number of his later productions, the director sought out Grant for his lead, accomplishing this task on only the three aforementioned occasions (frequently due to Grant’s busy schedule or high price tag). Few of Hitchcock’s leading men compare. James Stewart, Hitchcock’s recurrent voyeur, exists as Grant’s only competition.

Only the stellar blonde beauty of Grace Kelly compares as Hitchcock’s supreme female archetype, yet with Ingrid Bergman, Hitchcock shared a curious link. Rumors circulated around Hollywood for years about a romantic rendezvous in one of their homes, where Hitchcock arrived to find a willing Bergman coaxing him, yet she was turned down by the director—in spite of his persistent infatuation with his leading ladies, Hitchcock was also a gentleman and loved his wife. Many critics and scholars rightfully balk at this story, sometimes retold by Hitchcock after a few drinks, details wavering. Certainly, it was a piece of mid-career Hollywood lore for the director to recount later in life. And yet, the story is not unbelievable. As Patrick McGilligan asks in his exhaustive biography, A Life in Darkness and Light, “Don’t actresses fall in love with their directors all the time?” A somewhat typical symptom and cliché in Hollywood is the actress smitten with her director, and so this would not be incredible for Bergman, who had affairs with directors before (including Victor Fleming). Perhaps she was overly consumed by her character in Notorious, as such a tryst could hardly occur while filming her other two Hitchcock films: Spellbound and Under Capricorn, wherein her characters are not the creature of open sexuality that is Alicia Huberman.

Years later, in 1978, when Alfred Hitchcock was honored by the American Film Institute with a Lifetime Achievement Award, he would join the likes of honoree directors John Ford, Orson Welles, and William Wyler. That night’s ceremony featured bittersweet sentiment on the director, whose physical health was waning and usual wit was blanketed by his modesty. François Truffaut and Ingrid Bergman hosted the event. After a series of testaments to the director’s brilliance, Bergman approached his table and presented him with the Unica key, an item she and Cary Grant mutually kept as a good luck charm since production on Notorious, for more than thirty years. She returned the key to him, and Hitchcock accepted it with a loving embrace from a dear friend. Bergman and Hitchcock’s connection was undeniable, whatever its origins or circumstances. Grant joined the two, knowing it would likely be the last time the three could be reunited.

Years later, in 1978, when Alfred Hitchcock was honored by the American Film Institute with a Lifetime Achievement Award, he would join the likes of honoree directors John Ford, Orson Welles, and William Wyler. That night’s ceremony featured bittersweet sentiment on the director, whose physical health was waning and usual wit was blanketed by his modesty. François Truffaut and Ingrid Bergman hosted the event. After a series of testaments to the director’s brilliance, Bergman approached his table and presented him with the Unica key, an item she and Cary Grant mutually kept as a good luck charm since production on Notorious, for more than thirty years. She returned the key to him, and Hitchcock accepted it with a loving embrace from a dear friend. Bergman and Hitchcock’s connection was undeniable, whatever its origins or circumstances. Grant joined the two, knowing it would likely be the last time the three could be reunited.

A synchronization of thrills and affectionate drama drive Notorious, a career-encompassing model of Alfred Hitchcock’s approach to the kind of storytelling where a meaningless MacGuffin allows screen suspense to play out. And yet, the picture is made in a style and with a narrative that disestablishes the traditional elements associated with an Alfred Hitchcock film, where blondes are rescued by wrong men. Immersed in Hitchcock’s spy tale, his audience discovers a romantic interior unmatched in the director’s career, but also the prime example, in an almost endless continuation of examples, of Hitchcock’s genius. In choosing this picture as “quintessential Hitchcock,” Truffaut correctly avoided more popular choices like The Birds or Psycho, or even the director’s other two central pollinators Vertigo and North by Northwest. Here the director activates his clever MacGuffin to manipulate his viewers into an emotionally involving, harrowing experience, and therein exposes how plot devices mean nothing next to the narrative they reveal. No other single Hitchcock film tells us so much about how his cinema functions, and no other Hitchcock film functions in such a thrilling, romantic way.

Bibliography:

Krohn, Bill. Hitchcock At Work. Phaidon, 2000.

McGilligan, Patrick. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. Regan Books, c2003.

Modleski, Tania. The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory. Routledge, 2006.

Petrie, Graham. Hollywood destinies: European directors in America, 1922-1931. Wayne State University Press, c2002.

Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. Pantheon, 1988.

Schickel, Richard. Cary Grant: A Celebration. Little, Brown, c1983.

Schickel, Richard. The Men who made the movies: interviews with Frank Capra, George Cukor, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Vincente Minnelli, King Vidor, Raoul Walsh, and William A.Wellman. Atheneum, 1975.

Truffaut, François. Hitchcock. With the collaboration of Helen G Scott. Simon and Schuster, 1985.

Žižek, Slavoj. Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock). Verso, 1992.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review