Tornado

By Brian Eggert |

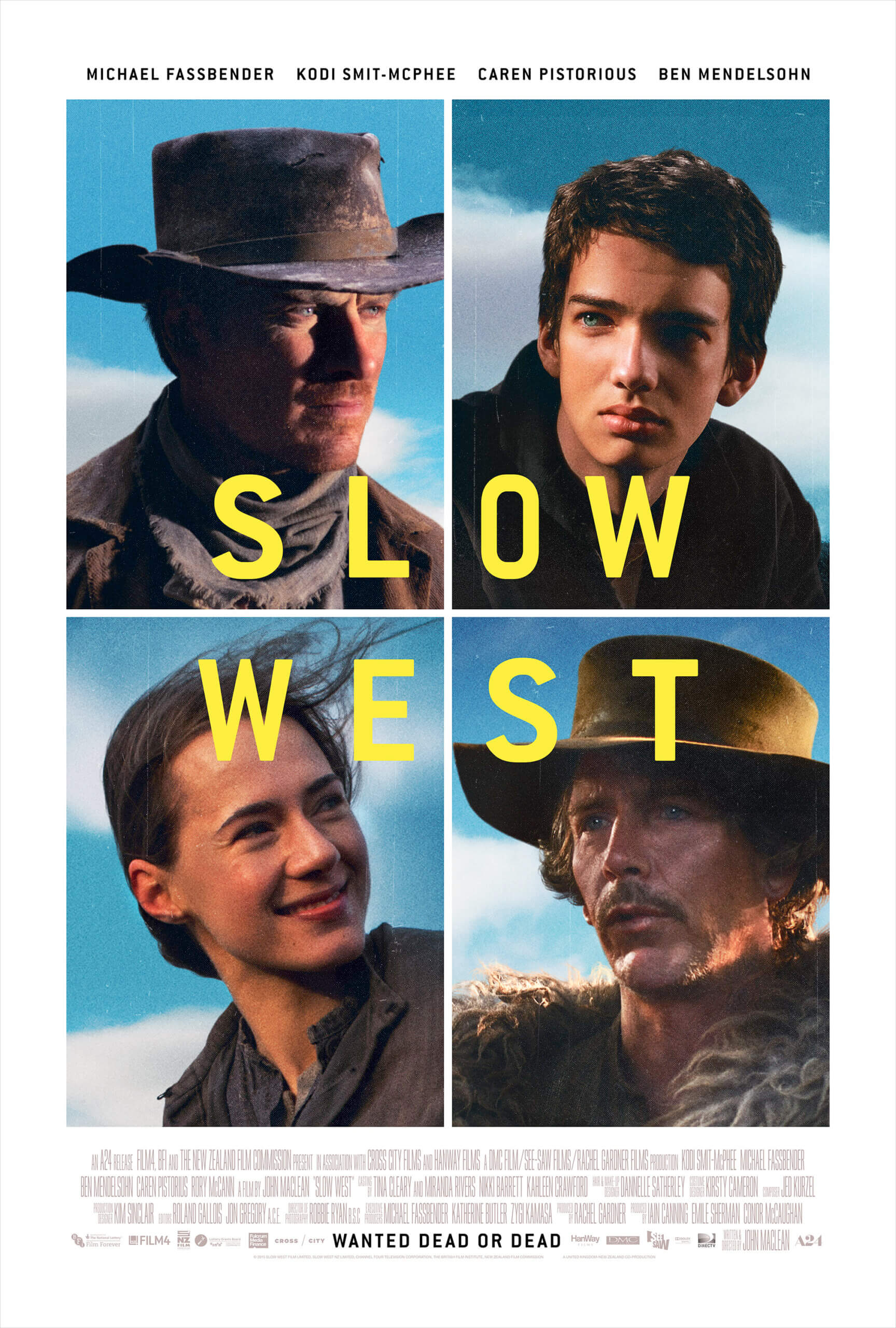

A decade has passed since John Maclean’s superb debut film, Slow West (2015), and the writer-director’s long-awaited sophomore effort, Tornado, is an underwhelming follow-up. Both films unfold in a similarly spare, natural setting that, if not situated literally in the American West, draws from Western imagery so liberally that it may as well be. Both feature minimalist characters played by actors who can imbue their roles with presence to spare. And both owe a great deal to loaded silences and gorgeous landscapes, captured by cinematographer Robbie Ryan in luminous, painterly compositions that frame iconic-looking figures against dramatic backdrops. Maclean’s composer, Jed Kurzel, brother of director Justin (The Snowtown Murders, 2011), also returns, interrupting the quiet, intense passages with sudden bursts of strings and heavy drums. Tornado is altogether thoughtfully crafted, just as Slow West was, but it’s missing an emotional core that might’ve centered the film.

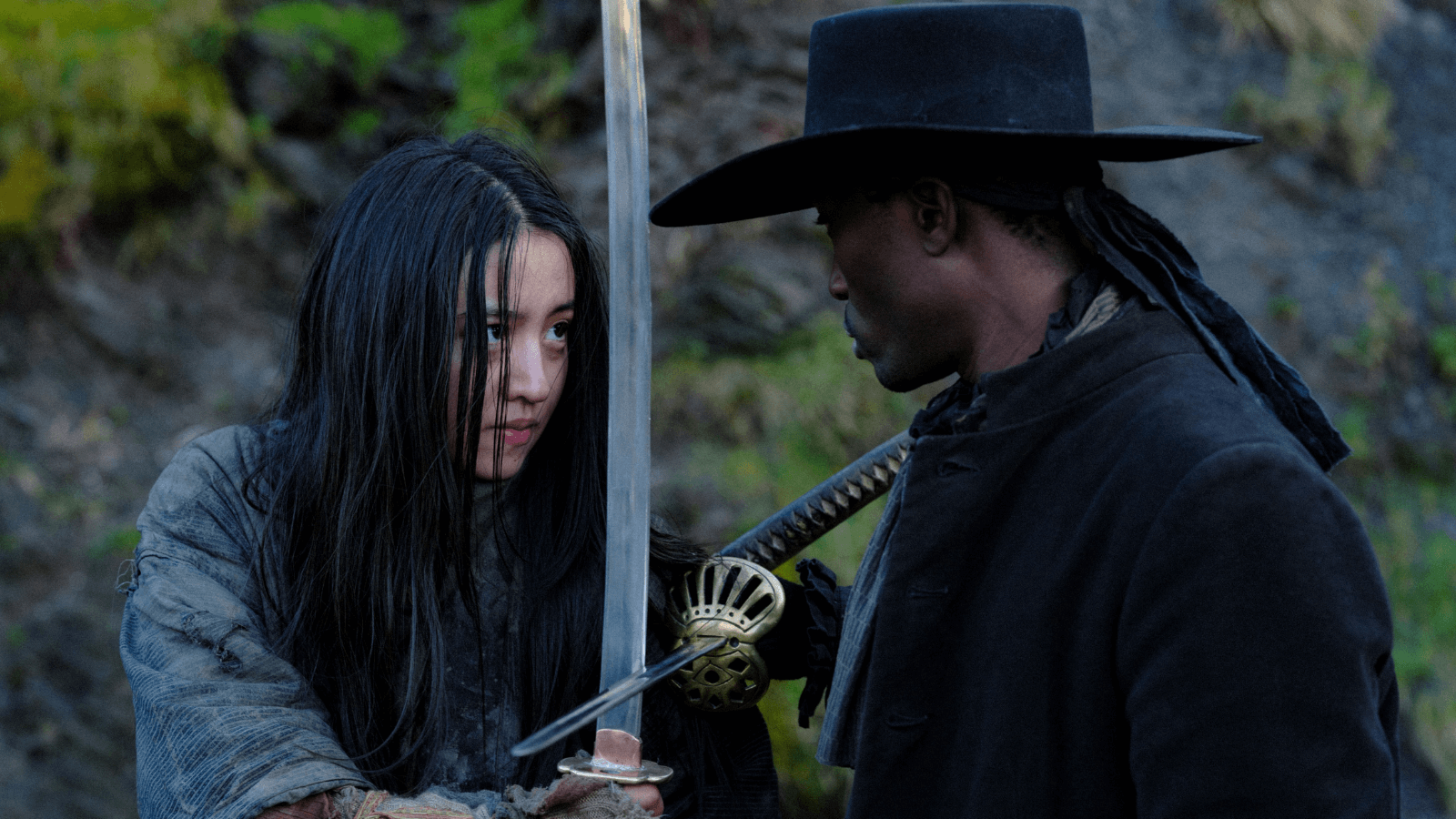

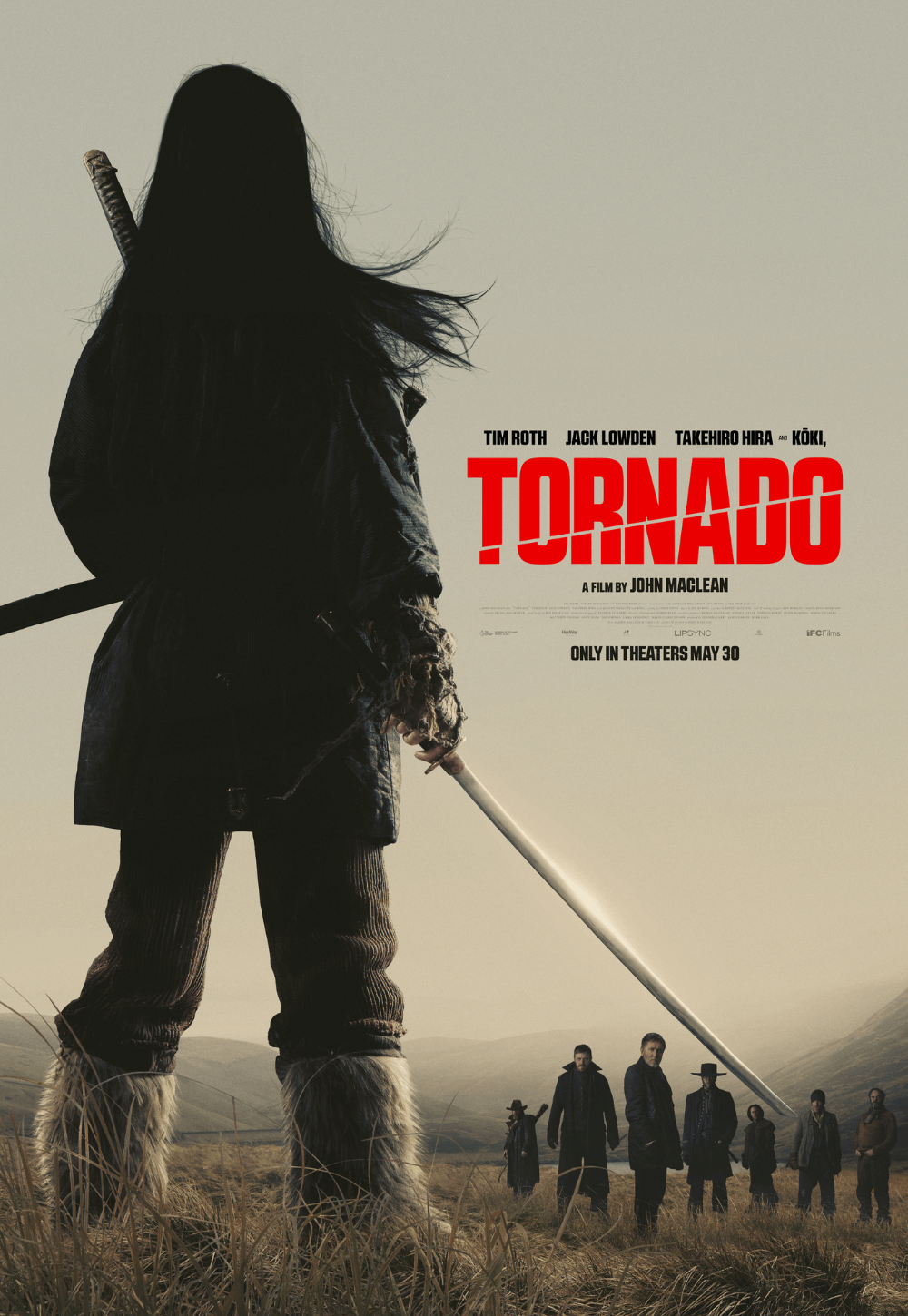

If Maclean’s interest in Western classics turned Slow West into an inspired homage to John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Anthony Mann, the filmmaker switches to Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah, and Akira Kurosawa in Tornado. Set on the Scottish countryside in the 1790s, the material almost plays like a post-apocalyptic story on par with The Road (2009), devoid of civilization, following a few scrappy outsiders who inhabit a near-mythic terrain. The first scene opens in medias res, with the titular hero Tornado (Japanese popstar Kōki) on the run across grassy, hilly country, from a wild bunch led by Sugarman (Tim Roth). Among the ten, the boss’ son, Little Sugar (Jack Lowden), buckles against his father’s rule. The other nine henchmen—with similarly cute names likeKitten (Rory McCann), Lazy Legs (Douglas Russell), and Psycho (Dennis Okwera)—prove more compliant yet have somewhat anonymous roles in this story.

Eventually, Maclean cuts back to a short while earlier, when Tornado and her father, Fujin (Takehiro Hira), perform a puppet theater show for a small, scattered audience, who seem to have no village nearby yet arrived in the middle of nowhere for this performance. The tension between the performers is palpable, with Fujin focused and his daughter impatient, tired of the same old routines. At the center of Tornado are two parent-child relationships, each involving a father who attempts to impart lessons and values to their defiant child. However, Maclean doesn’t explore this theme beyond superficial characterizations. He establishes that Fujin has taught Tornado how to use a samurai sword despite not mentioning the samurai principles outlined in the Bushidō Code. In Maclean’s hands, to be a samurai is an abstract cinematic concept, more inspired by a surface-level nod to Kurosawa’s ronin films, Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962), than the more profound understanding of samurai philosophy found in Seven Samurai (1954).

The plot entails Tornado lifting two burlap sacks of stolen gold from Sugarman’s posse, hoping to liberate herself and take a new path. The gang quickly identifies the culprit and hunts the father-daughter performers down, killing Fujin and prompting Tornado to avenge her father’s death. But Little Sugar schemes for the loot, compelled by the same selfish reasons as Tornado. What follows reminded me of A Field in England (2013), with a few rough types chasing after each other in spare fields that roll into the distance, its imagery more potent than its storytelling. A brief interlude finds Tornado hiding with a traveling troupe of performers, including a strong man (Raphaël Thiéry) and a knife thrower (Jude Cranston). Another filmmaker might have given them personalities or showcased their abilities. Instead, Maclean’s pseudo-samurai Western disposes of them almost as quickly as he introduces them, leaving only a missed opportunity for some added humanity or personality to this austere revenge story.

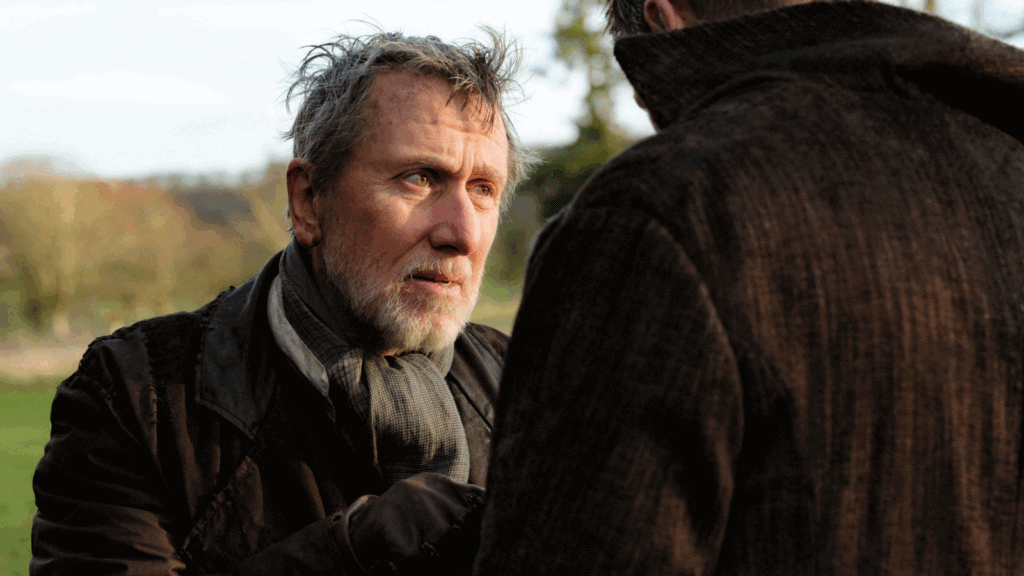

Shooting on location in the brittle Scottish winter, the production lasted 25 days, with Ryan employing 35mm celluloid for textured images and stunning light. Ryan captures the countryside’s beauty, where light interacts with the hazy skies and atmosphere to illuminate the setting. Visually, Tornado is a breathtaking picture, and only occasionally do Maclean and Ryan lift directly from specific sources—a shot replicated from The Sword of Doom (1966) stood out to me. Maclean’s blocking also suggests the operatic stillness of Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), with characters who fill space with long silences. Maclean doesn’t seem as invested in his characters’ faces as Leone was, though, leaving Sugarman’s crew a hodgepodge of forgettable goons that add to Tornado’s body count. Roth’s face remains singular among the cast; his expressions are unflinching and imposing, but also exhausted, grizzled, and impatient.

Despite the sudden deaths and blood-spurting effects, Tornado registers as an actionized samurai-Western hybrid and also a tonal experiment within the framework of established genre modes. Next to Slow West, where Maclean’s writing gave the actors more to work with, the filmmaker’s latest feels stripped down and overly focused on style and homage. Played by Kōki in a performance summed up by a few poses and gestures, Tornado’s journey from rebellious adolescent to a novice warrior bent on revenge, slicing and dismembering her opponents with a sword, lacks a strong dramatic pull. That pull might have made these proceedings—however cool-looking—more than just a genre or aesthetic exercise. With its runtime (minus end credits) at just under 90 minutes, I was left wanting more humanity from this otherwise handsome and formally assured production.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review