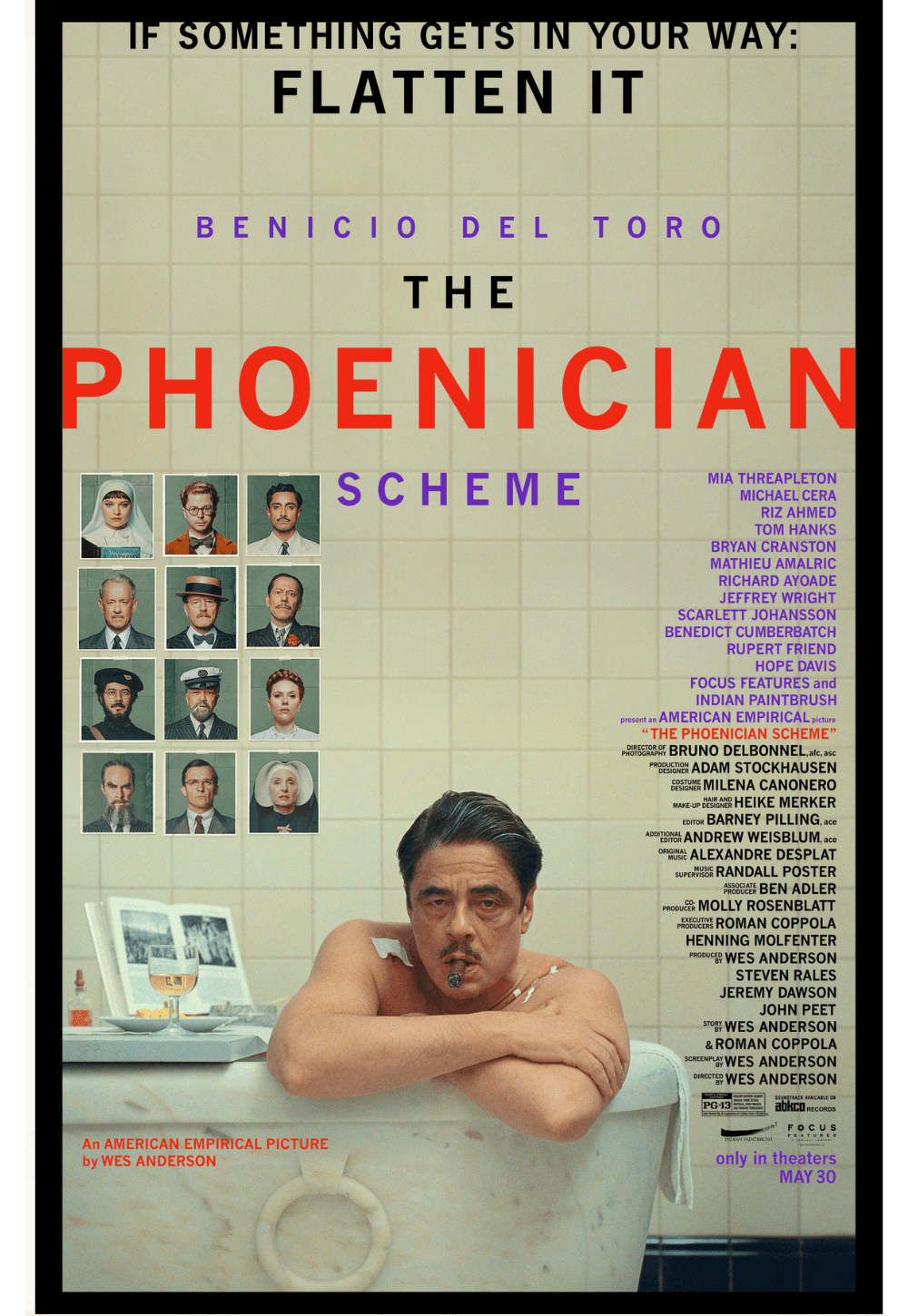

The Phoenician Scheme

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review of Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme was originally posted on May 24, 2025. The film arrives in theaters in wide release on June 6, 2025.

Wes Anderson’s last few films have operated similarly to his latest, The Phoenician Scheme. They hum along in his predictably fastidious, parodiable manner, deploying both random asides and narrative-driven scenes with the same attention to detail. And oh, what detail. Anderson and his team of designers in the production, costume, and graphic departments give every corner of the frame equal attention, ornamenting everything so meticulously that almost nothing stands out—the cinematic equivalent of Jackson Pollock’s all-over painting method or panoramic compositions in photography. Anderson and cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel present tableaus that flatten the screen image, directing our attention nowhere and thus everywhere. The narrative almost feels secondary to Anderson’s consideration of the image’s totality, brimming with fascinating touches and layered meanings. This quality enriches and hinders The Phoenician Scheme, an amiable if not-quite-essential entry in Anderson’s filmography.

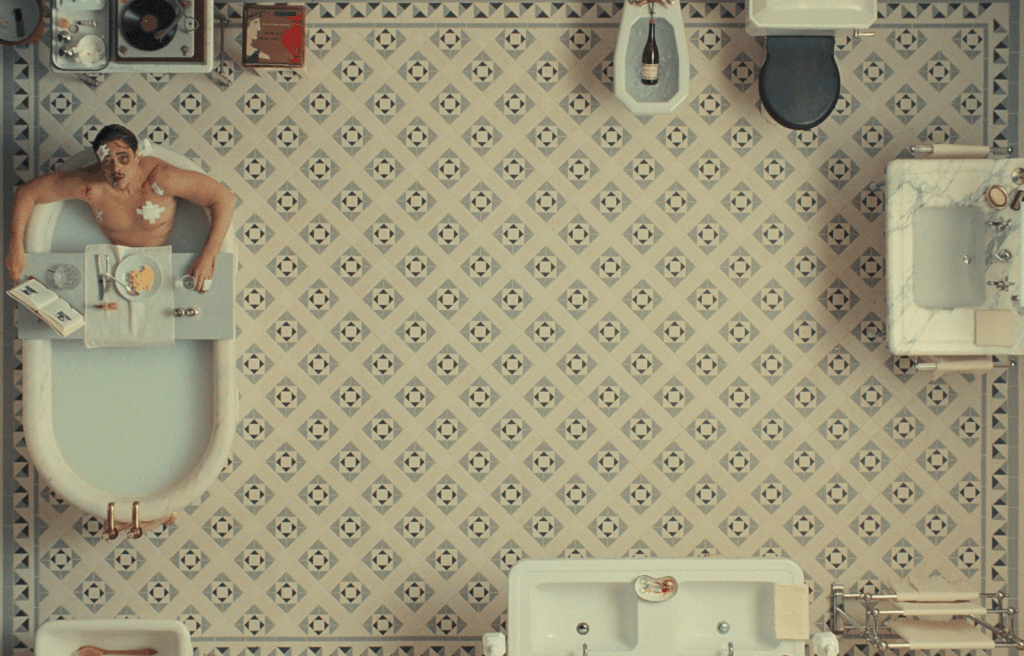

Consider the credits sequence, which features a shot looking down from above—recalling Brian De Palma’s early scene in The Untouchables (1987), where Al Capone gives an interview while receiving a shave. In Anderson’s film, set in the 1950s, nurses and attendants busily move around the elaborate en suite of Benicio Del Toro’s Zsa-Zsa Korda (his name a hybrid of socialite-actress Zsa Zsa Gabor and London Films founder Alexander Korda), a wealthy international businessman who takes his breakfast in the bath. Our eyes scan the image, absorbing how the credits font blends in with patterned tiles on the bathroom floor, how each character entering and leaving the frame feels inconsequential, and how Korda—despite his importance to the scene—is not a focal point. This sort of asymmetrical composition has its artistic purpose, ironically diverting our attention away from Korda, though most aspects of the story revolve around him.

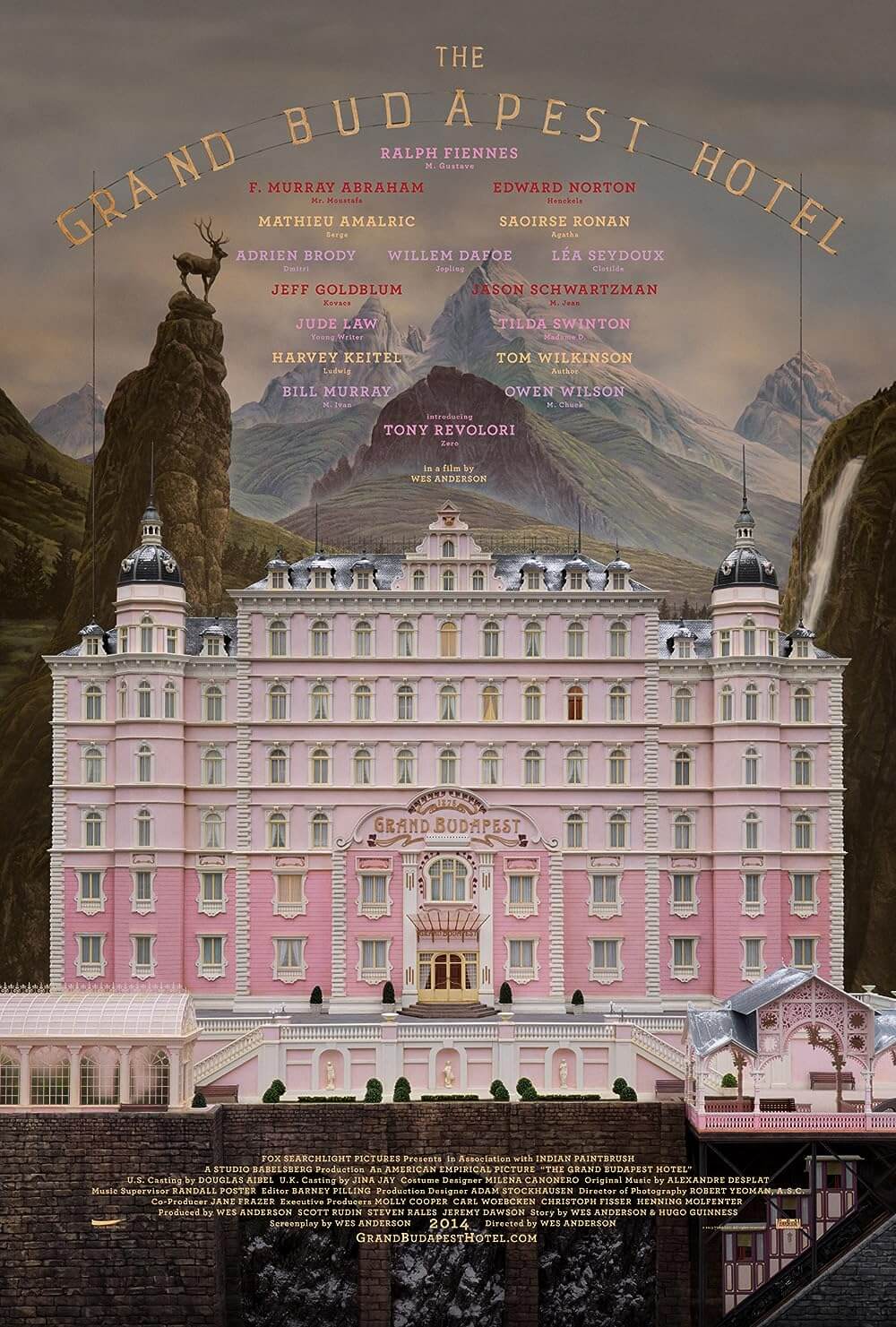

Anderson endures as a fascinating auteurist case study because his films now challenge me to consider what about them I value. When he first arrived on the scene with 1996’s Bottle Rocket, followed by Rushmore (1998) and The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), his approach registered as self-consciously stylized but reinforced by genuine emotions. Gradually, as Anderson became a master of meticulous form, his stories began losing their emotional impact on me. After The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), a perfect harmony of tenderness and ornately festooned aesthetics, and arguably his best film, Anderson’s focus became ever more committed to design and style over characters and drama—evidenced in Isle of Dogs (2018), The French Dispatch (2021), and Asteroid City (2023). This also coincided with Anderson no longer collaborating on his scripts. He co-wrote many of his earlier, more affecting films with Owen Wilson, Roman Coppola, Noah Baumbach, and Jason Schwartzman. They brought heart to his work, perhaps reining in his more unwieldy and obsessive tendencies. Lately, Anderson has been writing solo with no one to keep him in check.

His career path recalls that of Jacques Tati, the French master whose arthouse comedies began with warmth and humor in Jour de fête (1949), M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), and Mon oncle (1958), before turning into more painstakingly detailed and difficult-to-penetrate work in PlayTime (1967) and Trafic (1971). And yet, I adore Tati and his evolving style, which, like Anderson’s career progression, seems to become more concentrated with each new film. Perhaps I am more willing to embrace Tati’s undiluted artistic instincts because I can look at them from a historical perspective, whereas I have watched Anderson’s filmography unfold in real-time. Maybe in ten or twenty years, I will look back at The Phoenician Scheme and Anderson’s last few films and finally see what I’ve been missing. In the meantime, I yearn for Anderson’s films to move me again. For now, Anderson’s output reminds me of Rushmore’s Max Fischer, whose intricate productions and vast extracurricular activities disguise his inner pain. Anderson has become so good at distracting us with details that he’s forgotten that his characters occasionally need to halt their pretense and show their wounds.

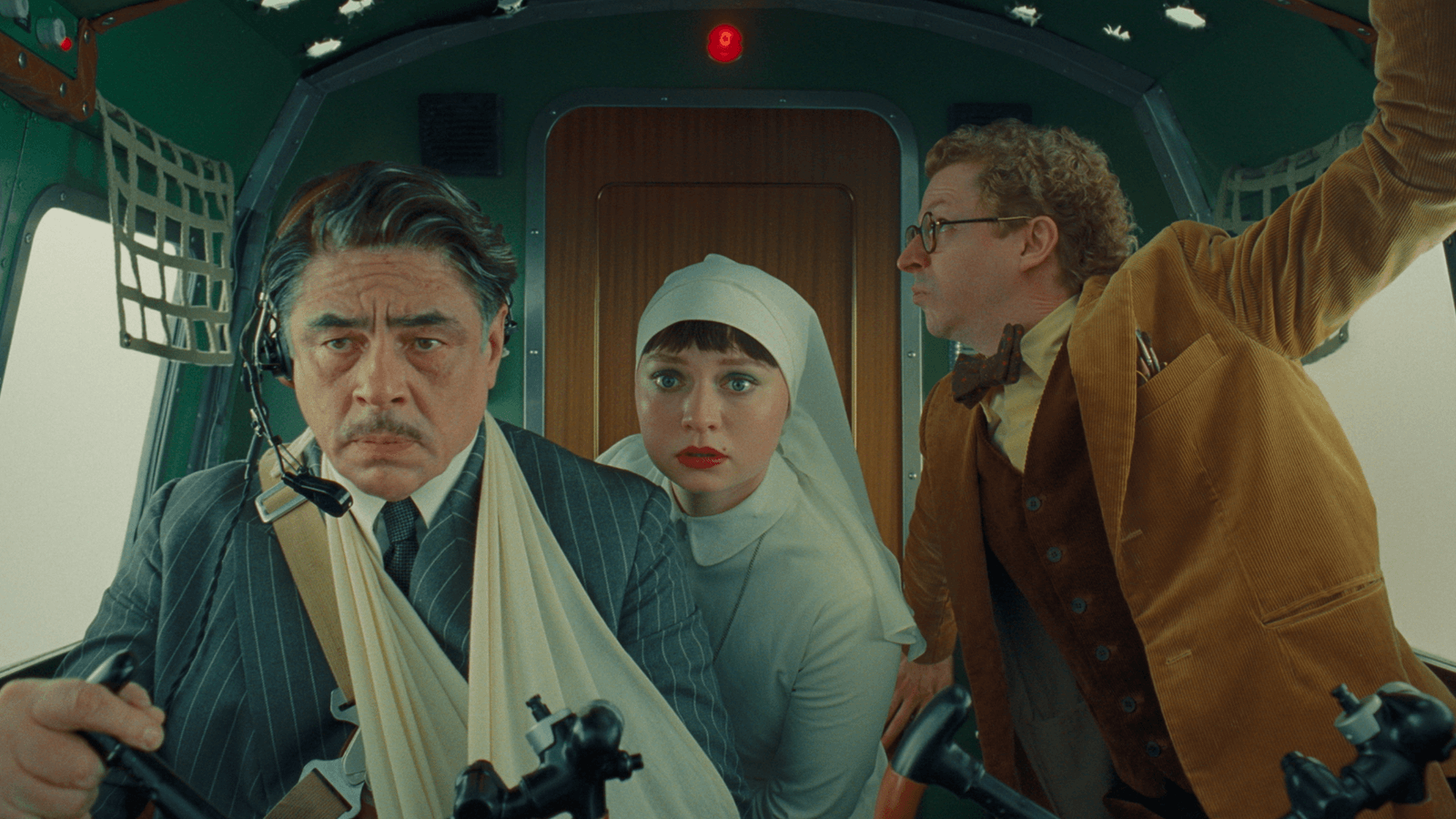

Accordingly, The Phoenician Scheme’s protagonist, Korda, has erected a tangled infrastructure around his business affairs. Refusing to call anywhere home, he travels around the globe and swindles everyone from industries to governments, earning enemies along the way. Most of them want him dead, so Korda narrowly survives a near-constant barrage of assassination attempts. Korda might be a genius; he knows a lot about a lot. He always travels with a small library of books and a tutor on a new subject. His latest interest is entomology, facilitated by expert Bjorn Lund (Michael Cera, whose Scandinavian accent wavers). Besides Korda’s entourage of assistants and employees, he has nine children with three wives; he has adopted even more children to play the odds. His sole daughter, Liesl (Mia Threapleton), is a nun in novitiate, but Korda expects her to give up her plans and take over his businesses. She’s the resident Michael Corleone, reluctantly pulled into her family’s shady dealings only to embrace them.

The title’s scheme entails Korda building a series of engineering projects, all relying on a particular brand of rivets. The US government, its head bureaucrat played by Rupert Friend, attempts to thwart the projects by driving up the price of those rivets. This requires Korda to meet with his various financiers to renegotiate their contributions. As usual, Anderson convinced half of Hollywood to appear: Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston play partners who settle the financial disputes with Korda over a basketball game. Mathieu Amalric plays a French nightclub owner. Benedict Cumberbatch is Korda’s ruthless and “biblical” brother, Nubar. Jeffrey Wright, Scarlett Johansson, Riz Ahmed, Richard Ayoade, and Hope Davis also appear. Meanwhile, Korda’s mortality weighs on him, prompting dreamy black-and-white sequences in a Heaven reminiscent of the one in A Matter of Life and Death (1946). In these stark, heavenly cutaways, Anderson regular Bill Murray plays God, Willem Dafoe plays a prophet, and Korda’s three dead wives sit in judgment—maybe because he murdered them.

One can see Anderson in Korda. They’re both control freaks. Korda even remarks at one point, “Why would anyone do something I didn’t tell them to do?” To be sure, Korda demonstrates his concern for the art of the deal more than matters of human rights—an uncomfortable subplot finds Korda arguing for slave labor and wondering why he should pay workers. Never mind the collateral damage in his wake; Korda believes in the sort of ruthless scheming and plotting that reinforce his reputation as “Mr. 5%”—a nickname earned for his skill at the bargaining table. Whereas Korda, and therefore Anderson, might seem to lack self-awareness about their tendencies at times, they also offer evidence to the contrary: Korda demonstrates his love for Liesl in his way, just as Anderson seems to recognize his fussy, even dehumanizing tendencies by making The Phoenician Scheme about a character not unlike himself, warts and all.

There’s no question that Anderson’s overloaded set pieces, characters, and filmmaking techniques construct an immaculate production accented with an exceptional score composed by Alexandre Desplat and shaped by multiple narrative framing devices. But a question continues to nag at me about this and other recent Anderson films: Did I feel anything profound, apart from detached admiration for Anderson’s complete control over the cinematic apparatus? Even Anderson’s perceived self-awareness as a Korda counterpart is delivered with muted emotions. Korda’s eventual acknowledgment of his behavior, and his love for Liesl, arrives in a small but wonderfully performed moment of recognition by Threapleton that carries the film’s emotional punch—and it’s not a knockout or gut punch; it’s a jab to the shoulder that snapped me out of the film’s formal spell. The Phoenician Scheme is easy to admire as a work of scrupulous precision, yet Anderson challenges his audience to feel something more for Korda. And I did, to the slightest degree.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review