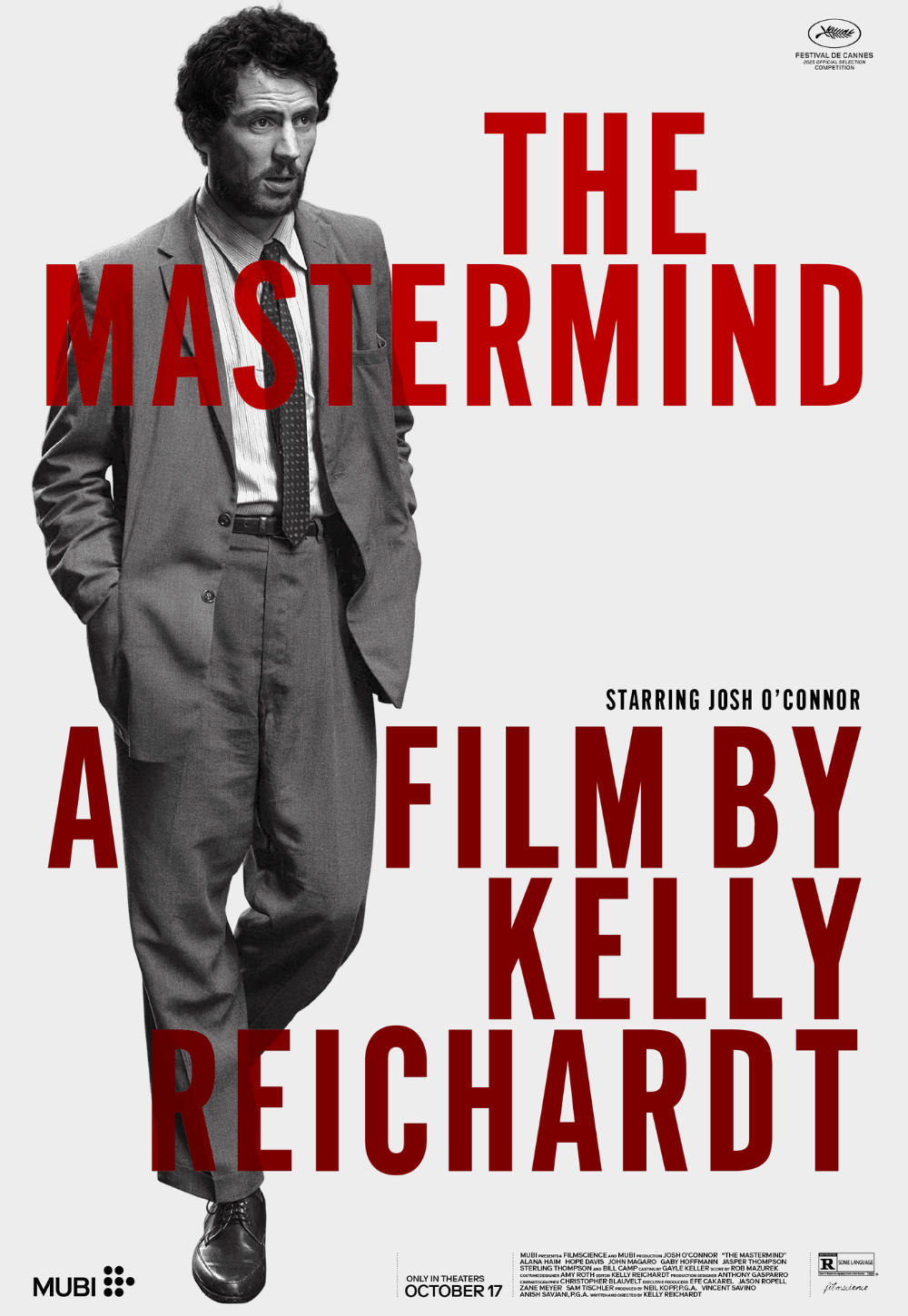

The Mastermind

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published on October 13, 2025. It has been reposted for its expansion into more theaters on October 24, 2025.

Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind opens in the Framingham Art Museum in Massachusetts. The year is 1970, and the Mooney family drifts around the galleries, passively looking at paintings while a security guard dozes nearby. The preadolescent boys, Tommy (Jasper Thompson) and Carl (Sterling Thompson), couldn’t be less interested in the artwork on the walls, with the former’s nose stuck in a comic book and the latter clinging to his mother, Terri (Alana Haim). Underneath the scene, Rob Mazurek’s jazzy score lends a mischievous tempo with a subtle bass line and brushes on cymbals that suggest something’s afoot. The music accompanies the father, JB (Josh O’Connor), an out-of-work schemer who has big plans for four Arthur Dove abstract paintings. For now, with his eye on the guard, JB carefully unlatches a display case—this is before museums had sensors and proximity alarms on their collections—and palms a small figurine, careful to avoid any sound or call attention to himself. This will be JB’s only successful theft in the film.

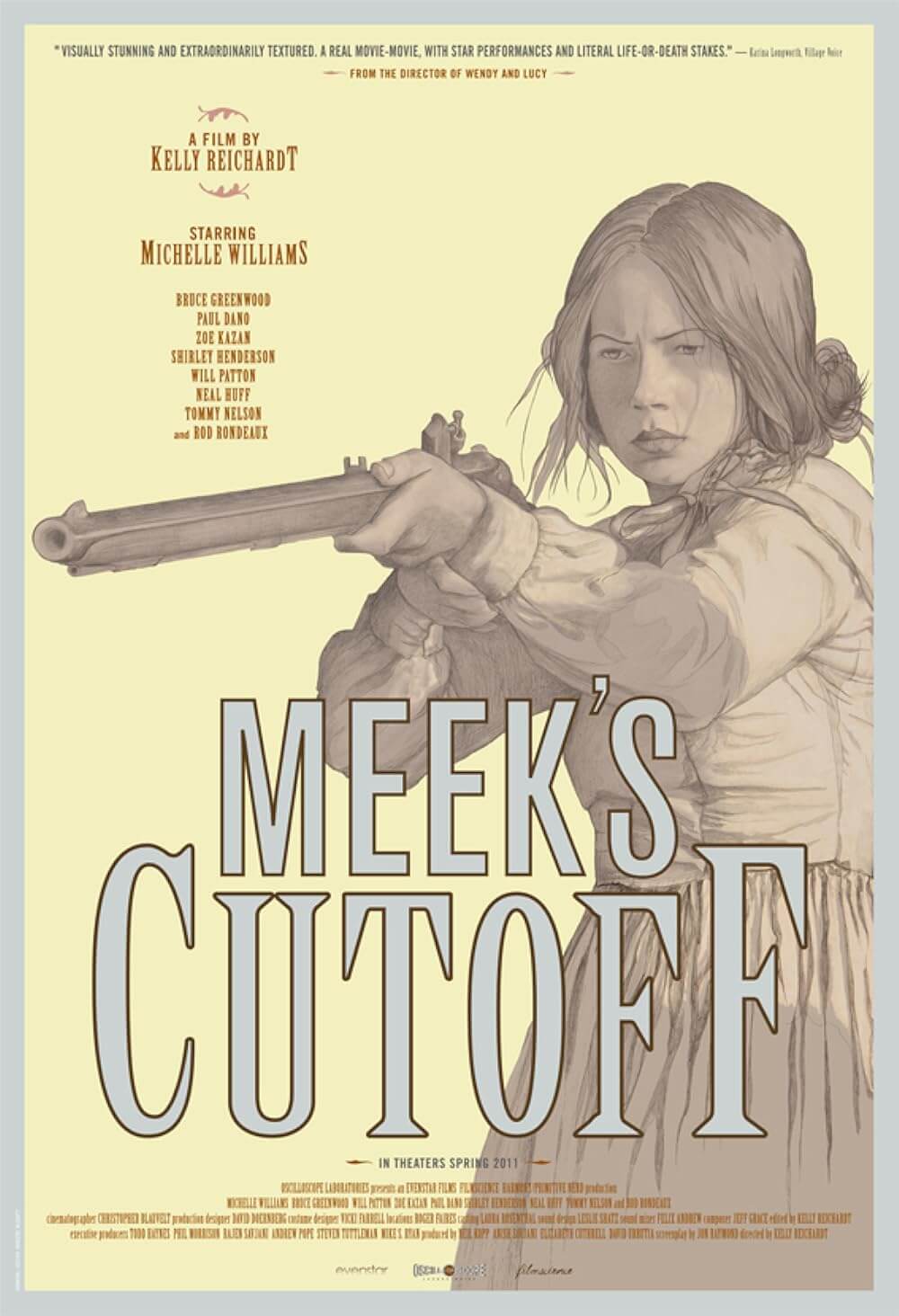

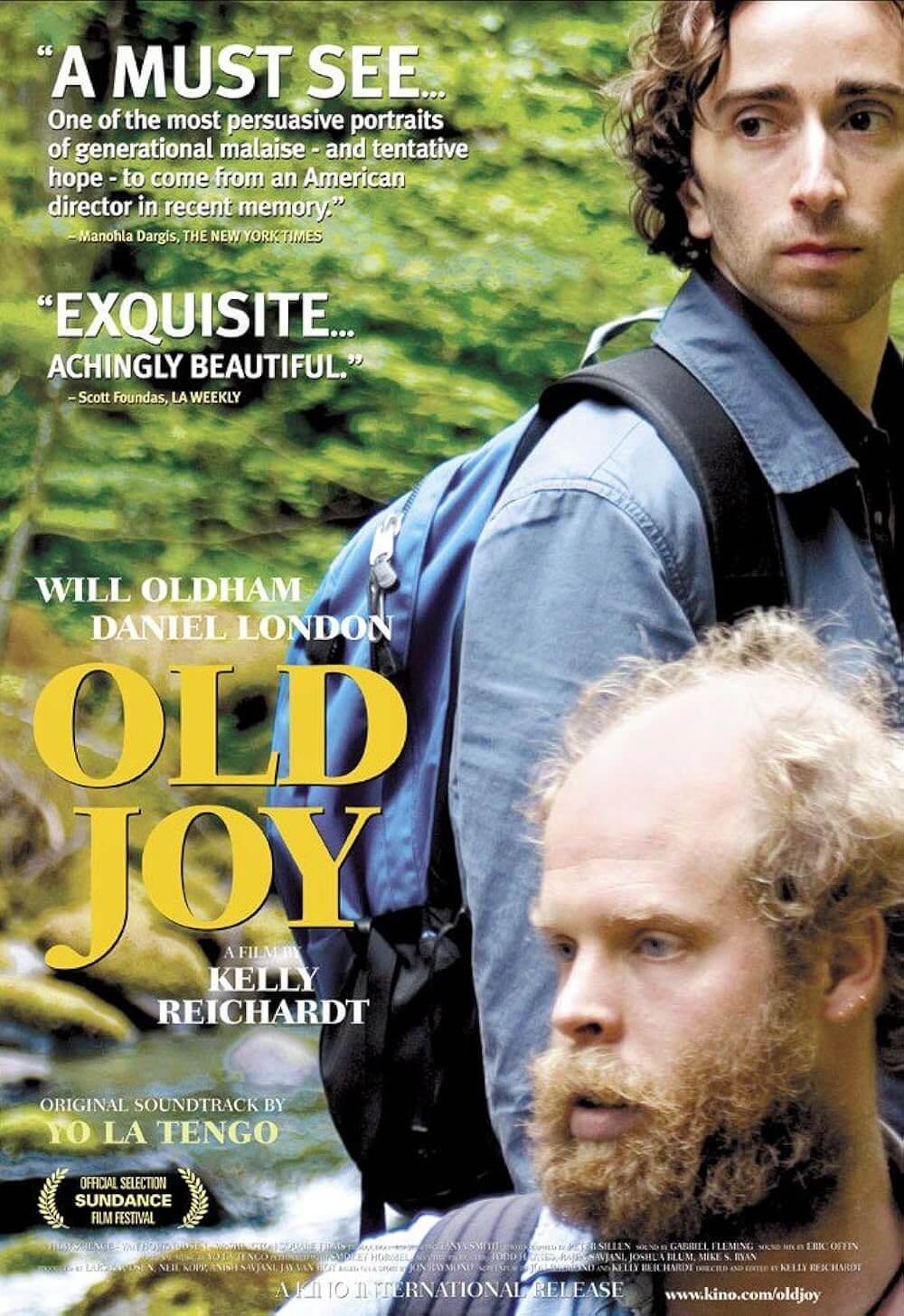

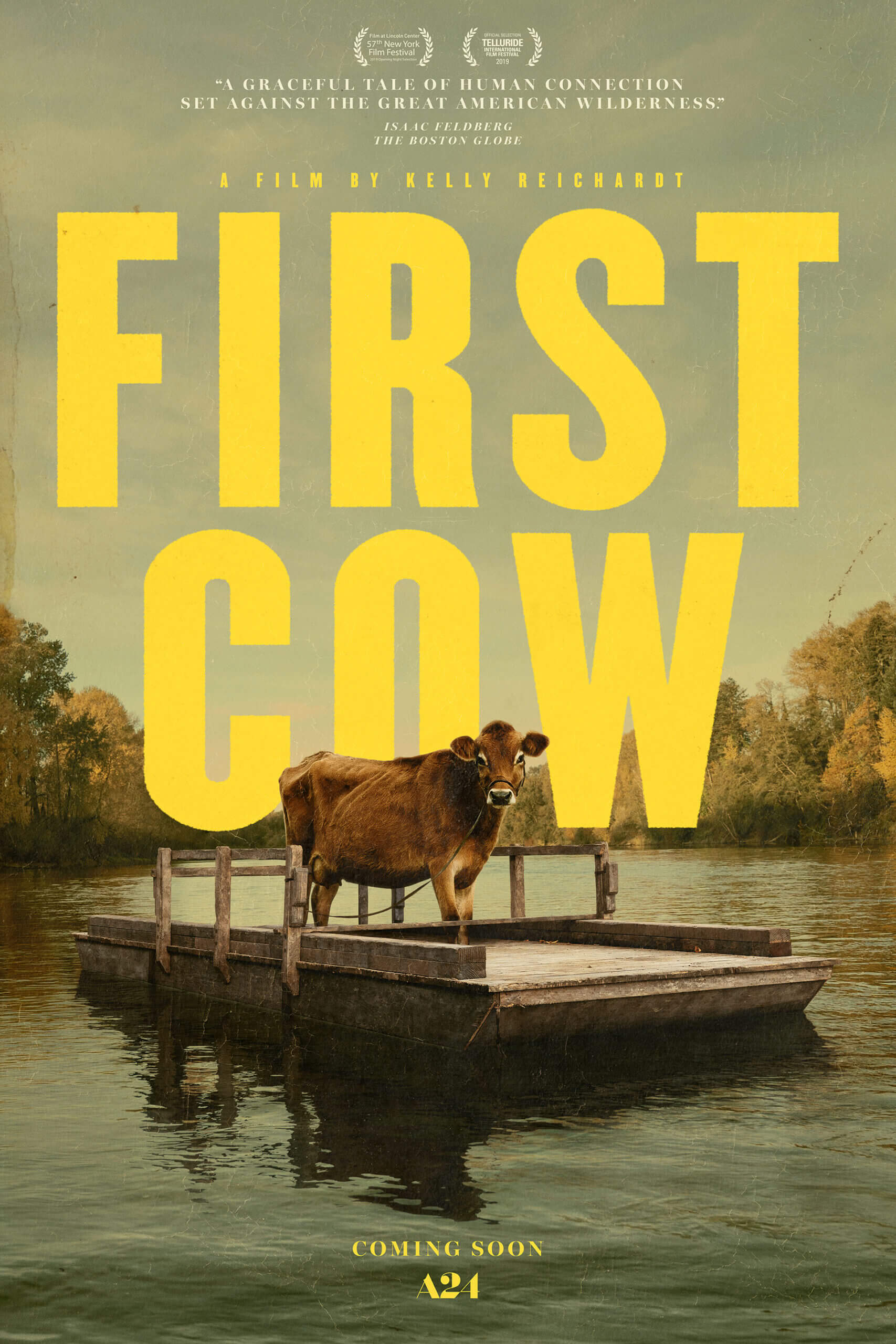

Reichardt continues to deconstruct genres in her latest effort, a wonderfully entertaining and slyly funny takedown of the masculine heist movie, where the lead proves not as smooth, cool, or intelligent as he perhaps imagines himself to be. Firmly situated in the heist-gone-bad realm of this genre, The Mastermind rethinks the mythmaking quality of many decidedly masculine master thieves from cinema, who demonstrate their prowess by outsmarting authorities and often other criminals, while preparing for every eventuality well before the audience or anyone onscreen has thought that far ahead. Reichardt often rethinks genre tropes and the aggrandizing stories usually told by men about other men. She disentangled the male-bonding buddy movie in Old Joy (2006), rethought the Western in Meek’s Cutoff (2010) and First Cow (2020), and deromanticized the eco-thriller with Night Moves (2013); she even eviscerated her audience’s emotional stability with her female take on a boy-and-his-dog tale in Wendy and Lucy (2008).

The Mastermind is another of Reichardt’s examinations of unchecked male entitlement as a flawed concept, comparable to how Stephen Meek claimed he knew a shortcut to the Oregon Trail and ended up lost. As cinematic thieves go, JB has more in common with the Wet Bandits than with Danny Ocean, Thomas Crown, or Dom Cobb. Marvelously played by O’Connor, one of today’s most dynamic and watchable performers, JB has the curly-haired mop and mischievous smile of Elliot Gould in The Long Goodbye (1973). In his basement, he pitches a scheme, which he claims to have been planning for some time, to his friends Guy (Eli Gelb) and Larry (Cole Doman). But he has no museum blueprints or elaborate timetable to follow. His plan involves L’eggs pantyhose as masks, a hotwired stolen station wagon, and a former drug-dealing wildcard named Ronnie (Javion Allen). Two masked men will enter the museum, place four Dove paintings into cloth sacks without waking the sleeping guard, and run out the front door, past the doorman, to the getaway car.

Even if the plan seems flimsy, Reichardt almost fools us into thinking JB might pull it off, in particular because of O’Connor’s confident screen presence. That’s a sharp deception on her part, casting this actor in this role. Watching JB assemble the pieces of his heist, he carries a certainty and intentionality to his gestures, as though he’s done this a million times. He hasn’t. Rather, he studied carpentry and art history as a post-grad and has been out of work for some time. Each morning, JB stays home, walking around in his boxers, a sweater, and socks, while Terri takes the kids to school, goes to work, and comes home to make dinner. What does JB do? Not much. It’s worth questioning to what extent Terri is aware of his plans. After all, she makes the cloth sacks on her sewing machine, and when her husband steals the figurine in the first sequence, he slips the item into her purse inside a glasses case. But outside, he sneaks the case back. And later, when speaking with his cohorts, he shushes them when Terri begins to come downstairs so she doesn’t hear their plans. She has to know he’s up to something.

O’Connor carries a similar vibe to his character in last year’s excellent La chimera, complete with a scruffy appearance and affinity for art. Except, that character looks brilliant and clever next to JB, who cannot catch a break the morning of his heist. A teacher’s workday means his kids don’t have school—which he should have known—and with no other options, he gives them some cash and drops them off at the bowling alley. Then, one of his crew drops out suddenly, requiring JB to serve as the getaway driver. His best laid plans are further thwarted by two female students in the museum and an unpredictable thief who shows up with a gun. Even so, they get the paintings, and JB hides them away in the loft of a nearby barn, protected by a wooden box he built. For a moment, he appears to have gotten away with it, until two detectives show up at his house. They explain that, after the art heist, Ronnie robbed a bank, got caught, and named him as an accomplice.

How is JB going to get out of this one? Easy. His disapproving father (Bill Camp) is a well-known judge in the area, and simply mentioning his name prompts the detectives to leave. Reichardt’s script establishes JB as incapable of self-reliance and dependent on his privilege. For instance, to fund his robbery and pay his accomplices, he appeals to his mother (Hope Davis), concocting an elaborate story about a carpentry commission that requires him to buy tools and a workspace. She reluctantly agrees to write him a check, provided he keeps the loan a secret from his father. Other cinematic thieves would plan a small job to fund their larger score. Not JB. What’s fascinating about how Reichardt has written him, and how O’Connor plays him, is that JB is likable, and despite his tendency to fuck up and make terrible choices, we root for him. But gradually, Reichardt characterizes him as incompetent and quite despicable. A scene late in the film finds JB desperate for money, and he targets an older woman with a wallet full of cash for a quick purse-snatching—and she’s not the only senior citizen he preys upon.

Working once again with cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt, her regular cinematographer since Meek’s Cutoff, Reichardt presents a soft-filtered and earth-toned aesthetic against the autumnal setting, vaguely reminiscent of 1970s cinema. The work of Hal Ashby came to mind watching The Mastermind, not only for its look, but for its interest in a bumbling outsider. Her characters dress in period-appropriate browns, greens, and oranges courtesy of costume designer Amy Roth, who captures the style of the period without calling attention to her efforts. Production designer Anthony Gasparro, too, offers subtle elements that immerse the viewer in the proceedings. Reichardt casts actors who disappear into the 1970s milieu, such as Haim, who already proved she belongs in that decade in Licorice Pizza (2021). But there’s also Gabby Hoffmann and John Magaro, who play JB’s old friends, a couple of country hippies who give him a place to hide out for a night.

As ever, Reichardt is an efficient writer. She resists the usual trappings of a heist movie by omitting otherwise expository scenes we might usually see in this fare, such as the thief outlining his plan or explaining to his wife why she must stay with his parents. When three men grab JB and force him to give up the paintings, Reichardt doesn’t bother identifying them. We can guess. She trusts her audience to put things together. And so, what seem like minor scenes reveal JB’s true colors, as seen when he almost blames Terri for not having more faith in him—as though he’s owed some measure of respect for messing up their lives. But he’s incapable of taking responsibility for his actions. Reichardt’s portrait of JB extends to the film’s background details. An undercurrent involves news bulletins about the Vietnam War and eventually anti-war student protests that play a larger role in the finale. JB has no stake in the protests, but he’ll use them to his advantage.

Throughout this entire, rather unaffected, quietly brilliant film, Mazurek’s jazz score reminds us that JB isn’t so much a mastermind as an improv artist, making things up as he goes. And while many cinematic thieves must pivot in ways that capture their nimble minds and ability to think on their feet, Reichardt’s thief belongs in a camp of witless criminals from the Coen brothers’ cinema—JB has much in common with Llewyn Davis or the ensemble from Burn After Reading (2008). But his simultaneous charisma and deplorable actions evoke Robert Pattinson’s whirlwind character in Good Time (2017) as well. By the almost punchline conclusion, which recalls After Hours (1985) in its ironic doom, Reichardt turns JB into a comic disaster who deserves what he gets. The film explores how individuals like JB manage to endure, relying on others and exploiting those around them, with a persistent feeling that the universe owes them something for merely existing. In today’s world, overrun by entitled white guys incapable of owning up to their behavior, it’s refreshing to see one receive his comeuppance.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review