The Holdovers

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published for the Twin Cities Film Fest. Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers opens on October 27, 2023.

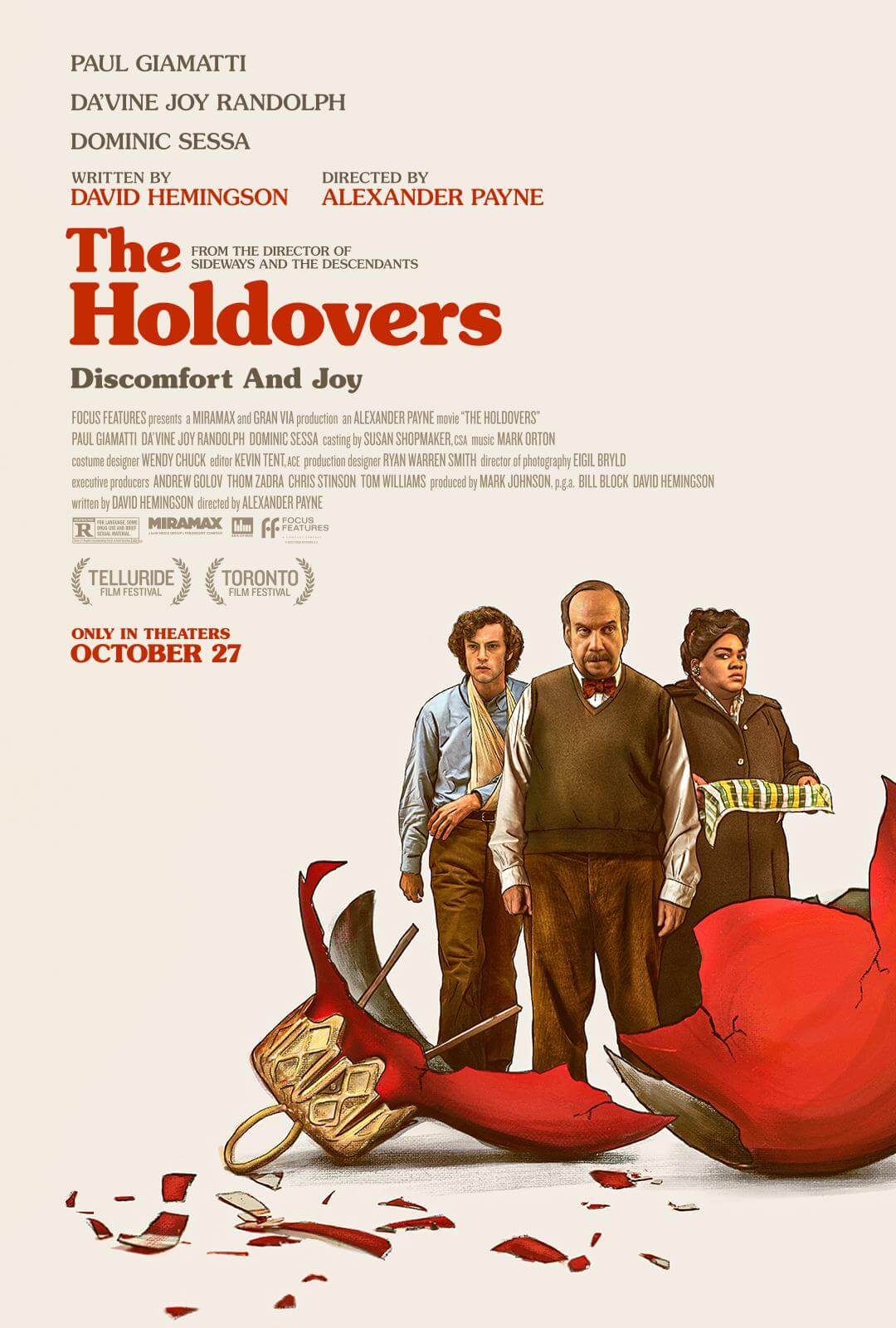

The Holdovers may be an imitation Hal Ashby film, but it’s a pretty convincing fake. Directed by Alexander Payne, the film demands comparisons between Ashby’s cinema and Payne’s similar interest in misfits who take journeys of self-discovery. Surely, when Payne read the screenplay by TV writer David Hemingson, the experience brought to mind Ashby’s Harold and Maude (1971) and The Last Detail (1973), and maybe even Being There (1979). In those examples, Ashby’s characters refuse to conform to conventional expectations and often defy the rules, learning hard lessons about life with notes of cynicism toward various establishments, while feeling emboldened by the freedom and power of individuality. Payne at least has the misfits and cynicism part down, evidenced in Election (1999) and Downsizing (2017), though he’s arguably just as derisive toward his characters as he is empathetic. Fortunately, many of these parallels hardly matter because The Holdovers is among Payne’s best films, largely thanks to its intelligent writing and terrific performances from the three leads.

Still, Payne draws on these similarities to Ashby’s work and accentuates them in The Holdovers, applying a nostalgia that not only harkens back to Ashby’s 1970s heyday but deploys familiar visual flourishes and needle drops within the film’s first moments. A Focus Features release, the film’s opening titles display an imagined vintage logo (the company was founded in 2002), followed by grainy film stock with pops and visible dust on the print. The opening credits almost imperceptibly shake onscreen, a quirk of ‘70s productions. Later, Payne and his cinematographer Eigil Bryld use long zooms, fades, and intimate close-ups that are more attuned to Ashby’s aesthetic than Payne’s. And in a film full of excellent tunes on the soundtrack, the conspicuous presence of Cat Stevens cannot help but recall Harold and Maude. Along with thesubtle CGI to render snow, all of these touches amount to a familiar albeit artificial something: A committed pastiche? A knock-off? An homage? However you define it, the film feels like Payne working outside his usual, less distinct formal mode and instead applying another director’s visual identity to his work.

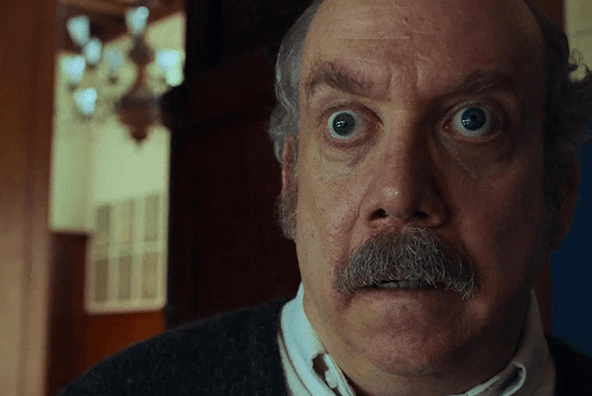

In another way, The Holdovers wields nostalgia for Payne’s indie darling, Sideways (2004), with the presence of star Paul Giamatti. Payne directed one of Giamatti’s finest performances in that film, and the actor outdoes himself here. The film opens just a few weeks before Christmas in 1970, on the campus of a New England prep school, Barton Academy. Giamatti plays Paul Hunham, an ancient civilizations instructor whom the students deplore. Hunham sits in the campus quarters he calls home, grading exams. “Lazy, vulgar, rancid little philistines,” he mutters to himself about his underperforming students over a morning serving of Jim Beam. With his exotropic eyes, pipe in mouth, sharp sense of intellectual superiority, and dogged adherence to academic principles, Hunham is an archetypal Giamatti character—a little funny looking, a bit angry, certainly petty, yet deserving of empathy. Later, we learn more about him, such as the condition that causes his distinct odor, or inevitably, the revelation that his identity might boil down to a single mistake that shaped why he laments academia’s politics and spoiled students who expect leniency on their grades because of their influential families.

Hunham is a delightfully complex and entertaining character, amusing and tragic, and Payne pokes fun at him but never robs him of integrity. When Hunham finds himself tasked with supervising students who have nowhere to go over the Christmas break, accompanied by the cafeteria manager, Mary (Da’Vine Joy Randolph, also excellent on Hulu’s Only Murders in the Building), he resolves to keep them busy with schoolwork, perhaps out of spite for their privileged lives. It’s not until most of the boys are rescued by one of their rich fathers that Hunham and Mary are left with just one rebellious yet intelligent teen, Angus (Dominic Sessa), whose mother and stepdad have abandoned him for the holidays to take their honeymoon. With only three of them on campus, the rules loosen, guards lower, and what might be the sad solitude of the Christmas season feels a little less melancholy once the trio forms a makeshift family. Hunham even begins to realize that privilege doesn’t necessarily preclude students like Angus from having serious problems.

Misadventures ensue, and Hunham’s defenses lower after he develops an understanding with Angus that their many mistakes over the holiday period shall be kept “entre nous.” A trip to the hospital, a Christmas Eve party, and a road trip have an almost One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) quality—which, incidentally, Ashby was originally poised to direct. Randolph remains on the sidelines mostly, but her few scenes resonate, marked by Mary’s loss of a child and husband. Each of these characters might be reduced to a trope in another filmmaker’s hands; however, Payne never allows the potentially wacky situations to overcome how these three people are more than their surface implies. Without overstating it, Hemingson’s script explores how Hunham, Angus, and Mary have arrived at individual crossroads where the winter setting seems to signal a grim finality, despite the holiday backdrop. That The Holdovers manages to end on a note of mild optimism could be viewed as sentimentalism on Payne’s part. However, the director’s brand of hopefulness feels more bittersweet than saccharine.

So when Hunham rants, “The world doesn’t make sense anymore,” it’s just a momentary descent into pessimism. Quite refreshingly, The Holdovers maintains a philosophy that no matter how difficult things may get, history can teach us how to deal with it. Hunham’s oft-tapped knowledge of antiquity has taught him that the limits of human experience have already been tapped, so stop acting shocked and use history—even if it’s your personal history—to inform how you process the present and change for the better. Then again, life can come at you in unpredictable ways and feel tragicomic, as this film often does. At 133 minutes, it begins to feel overlong in the end as it wraps up the story. But through the outstanding performances and heartrending situations, no matter how aesthetically familiar they may be, Payne has made a film bound to be revisited around the holidays by those who find the season somewhat depressing. It’s sure to bring plenty of laughs, and maybe a few tears, too.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review