The Fabelmans

By Brian Eggert |

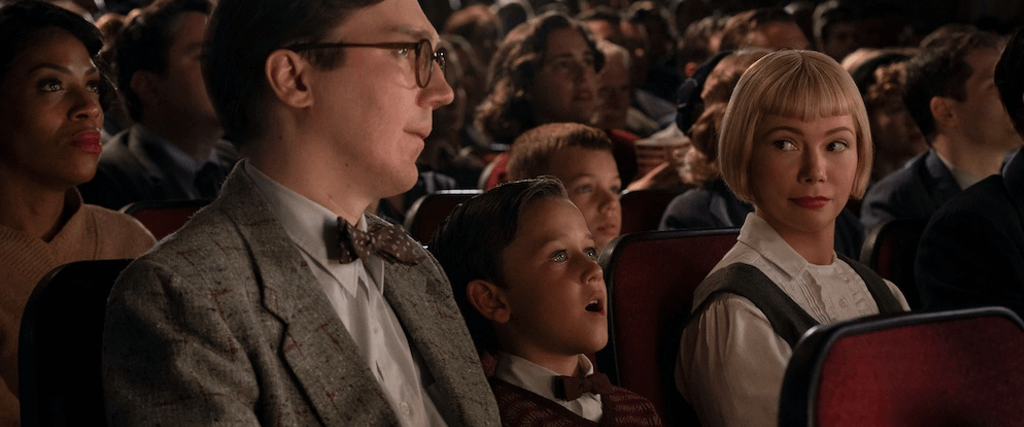

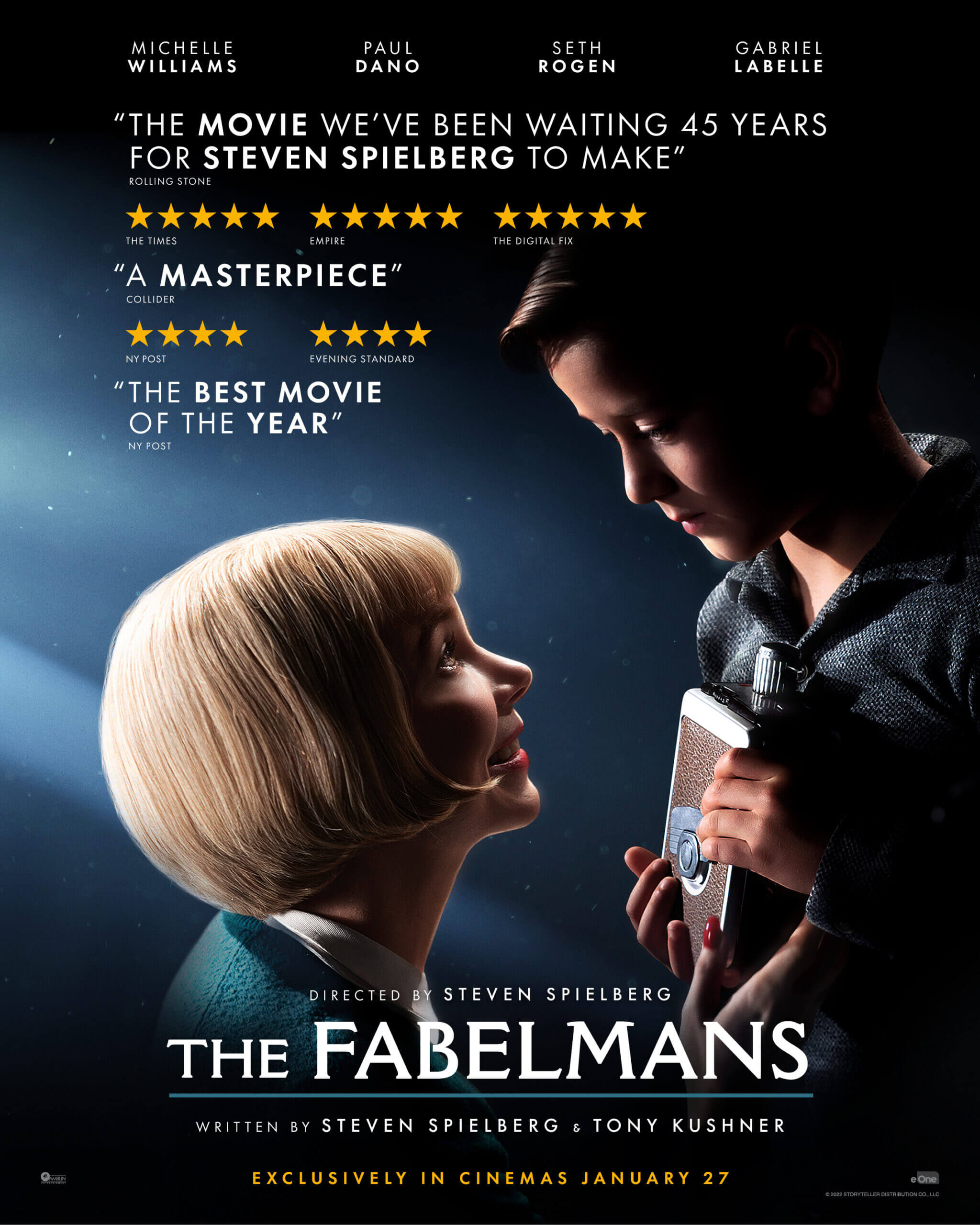

Standing outside a cinema in 1952, Mitzi and Burt Fabelman (Paul Dano and Michelle Williams) try to calm their 7-year-old son Sammy’s (Mateo Zoryon Francis-DeFord) apprehensions about seeing a movie for the first time. Burt crouches down and proceeds to explain the technical apparatus spinning 24-frames-per-second and the concept of “persistence of vision” to his son. Sammy’s mother takes a different approach: “Movies are dreams,” Mitzi says. “But dreams are scary,” her son replies. “Not all dreams,” she reminds him. Steven Spielberg’s autobiographical The Fabelmans is a self-mythologizing wonder and among the director’s best and most personal films. This moment in the opening encapsulates who Sammy, a stand-in for Spielberg (the titular storytelling fable-man), will become—an equal share of Mitzi and Burt, and a walking personification of film itself. Just as motion pictures are a transportive and dreamlike art, limited only by the imagination, they’re also a mechanical and scientific process. Similarly, Spielberg has consistently demonstrated a keen awareness of the technical aspects of filmmaking, but his childlike vision and virtuosity have inspired countless memorable images since his emergence in the 1970s. The Fabelmans is a coming-of-age tale about Spielberg’s early life and introduction to filmmaking. But it’s also a portrait of his influential parents, which acknowledges that without them, flaws and all, Spielberg wouldn’t have become one of the greatest and most successful directors of the last century.

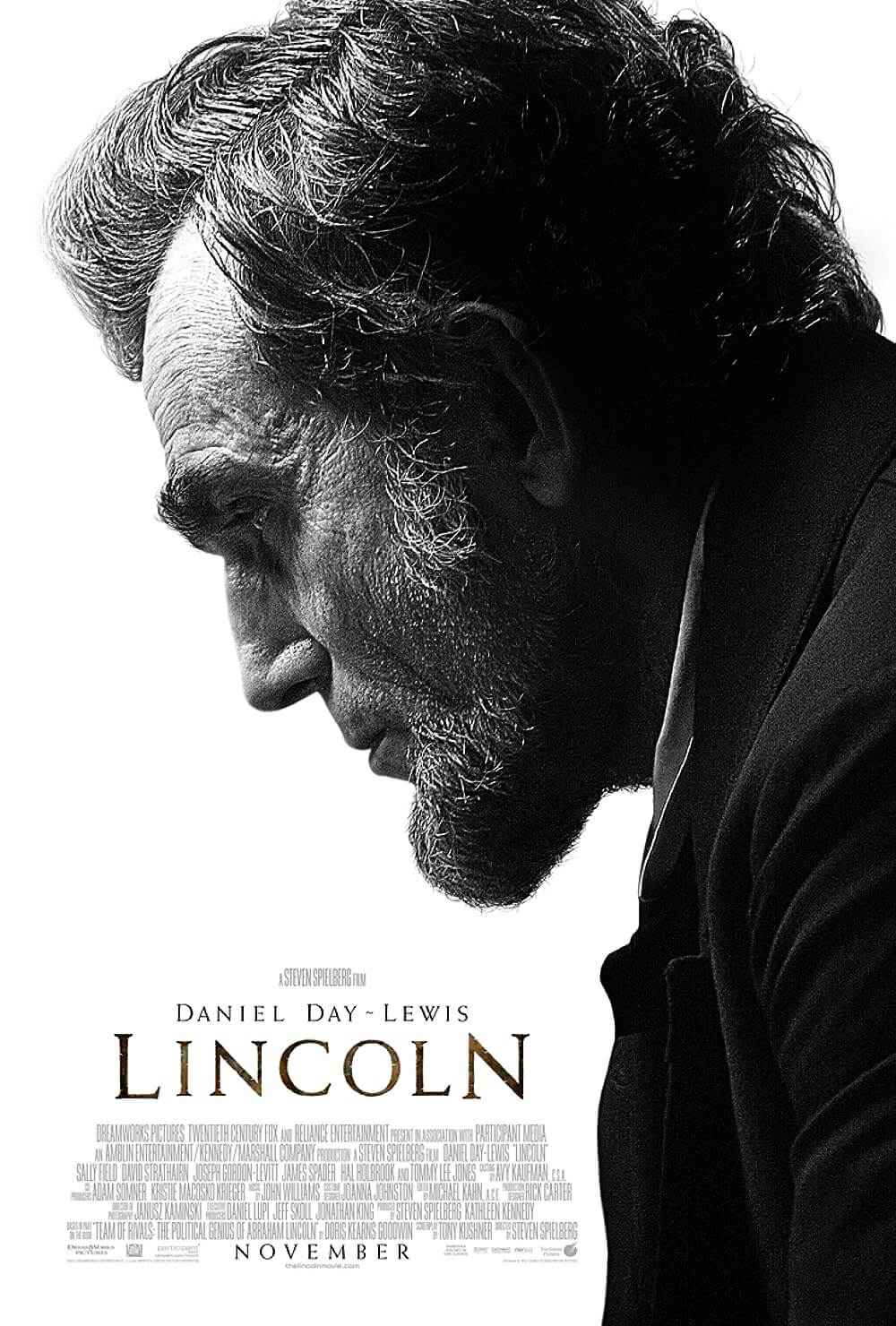

Back to the moviehouse: Sammy sits between Mitzi and Burt, and the Fabelmans bask in the Technicolor glow of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth. The famous train crash scene ignites in young Sammy’s mind. He is both terrified and transfixed, and his eyes glimmer in the movie’s light. His experience recalls those stories about the first time people saw the 50-second short “The Arrival of a Train” in 1896—they ducked and screamed, convinced they would be struck by a locomotive. Sammy undergoes something similar. Spielberg has told this story before, or versions of it, many times, including in the exhaustive (and rather excellent) biography by Joseph McBride. In his film, which Spielberg co-wrote with Tony Kushner—who contributed to the director’s Munich (2005), Lincoln (2011), and West Side Story (2021)—Sammy must work out his anxiety about the train crash he saw on the big screen by recreating that moment with his family’s 8mm camera and the train set he received over Hanukkah. Again, Burt takes the practical approach with his son, telling Sammy that he must take care of his expensive toy. But Mitzi understands Sammy’s need to see the train crash again and again with a film—to “make a little world you can be safe and happy in.” Thus began Spielberg’s need to process the world through filmmaking.

Of course, Spielberg has never been known as a particularly intimate or personal filmmaker. First and foremost, he is associated with commercial cinema and, in some circles, blamed along with George Lucas for turning Hollywood studios on to blockbuster paydays following his breakthrough with Jaws (1975). However, movie studio corporatization would have happened without Spielberg, as most industries became subject to the whims of conglomerates by the 1980s. In any case, Jaws, along with his other mainstream projects over the years—ranging from Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) to Schindler’s List (1993) to A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)—often find the filmmaker working through his sense of self, both as a storyteller and a human being. Some characters become unmistakable stand-ins for his absent father, while others show beleaguered mothers and forgotten sons, and others still grapple with their Jewish identity. Spielberg is more than simply an influence on the visual grammar of commercial cinema—although he is that, too. Rather, he’s an auteur who finds ways of weaving himself into his most marketable films. If The Fabelmans does nothing else, it gives audiences a reference point to rethink Spielberg’s earlier work through a biographical lens.

Similar to the way James Gray framed his childhood in this year’s Armageddon Time, Spielberg explores his home life in New Jersey with charming, lived-in details: how Sammy finds ways of tormenting his sisters on camera; how his mother uses disposable plates and tablecloths because she hates doing dishes; and how the omnipresence of Bennie (Seth Rogen), Burt’s colleague and best friend, presents a blithe component to the family dynamic, yet his presence seems strange. Soon, Burt, whose science and computer genius keeps him in demand with bleeding-edge tech companies, uproots the family and moves them to Arizona, away from Bennie, who will eventually join them. But for now, Mitzi responds with borderline panic. She gathers her children in the family car and drives toward chaos—a tornado swirling in the distance, recalling the final scene from the Coen brothers’ A Serious Man (2009)—and leaves Burt behind with their new baby. The children wonder whether it’s safe. “Of course it’s safe,” Mitzi explains. “I’m your mother.” For whatever the scene tells us about Mitzi’s fragile emotional state and affection for Bennie, the thrilling drive could have been a sequence out of a Spielberg adventure: power lines fall, cars crash, and violent winds propel a row of shopping carts to cross before the Fabelmans’ car, speeding by like the fiery train in War of the Worlds (2005).

Similar to the way James Gray framed his childhood in this year’s Armageddon Time, Spielberg explores his home life in New Jersey with charming, lived-in details: how Sammy finds ways of tormenting his sisters on camera; how his mother uses disposable plates and tablecloths because she hates doing dishes; and how the omnipresence of Bennie (Seth Rogen), Burt’s colleague and best friend, presents a blithe component to the family dynamic, yet his presence seems strange. Soon, Burt, whose science and computer genius keeps him in demand with bleeding-edge tech companies, uproots the family and moves them to Arizona, away from Bennie, who will eventually join them. But for now, Mitzi responds with borderline panic. She gathers her children in the family car and drives toward chaos—a tornado swirling in the distance, recalling the final scene from the Coen brothers’ A Serious Man (2009)—and leaves Burt behind with their new baby. The children wonder whether it’s safe. “Of course it’s safe,” Mitzi explains. “I’m your mother.” For whatever the scene tells us about Mitzi’s fragile emotional state and affection for Bennie, the thrilling drive could have been a sequence out of a Spielberg adventure: power lines fall, cars crash, and violent winds propel a row of shopping carts to cross before the Fabelmans’ car, speeding by like the fiery train in War of the Worlds (2005).

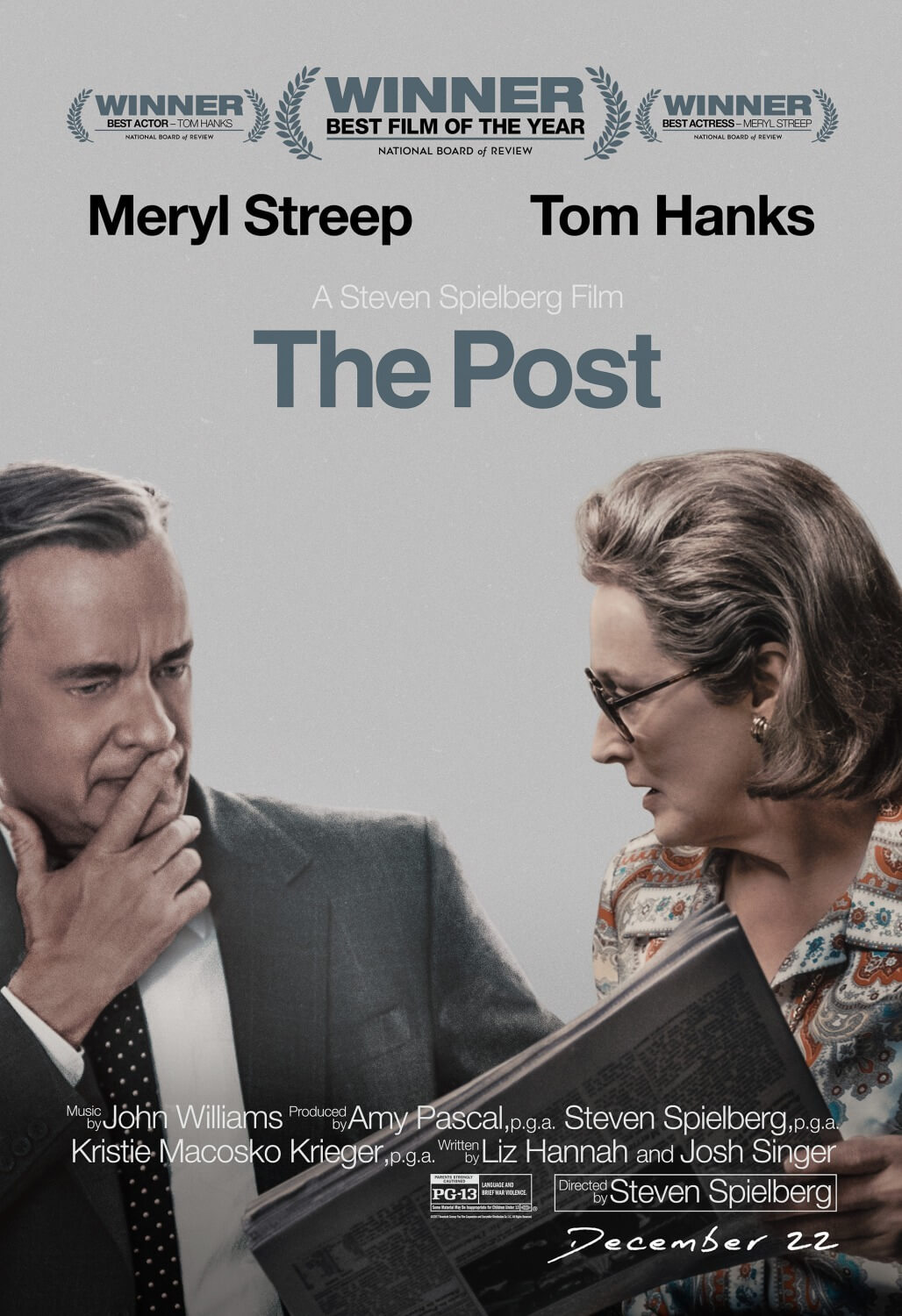

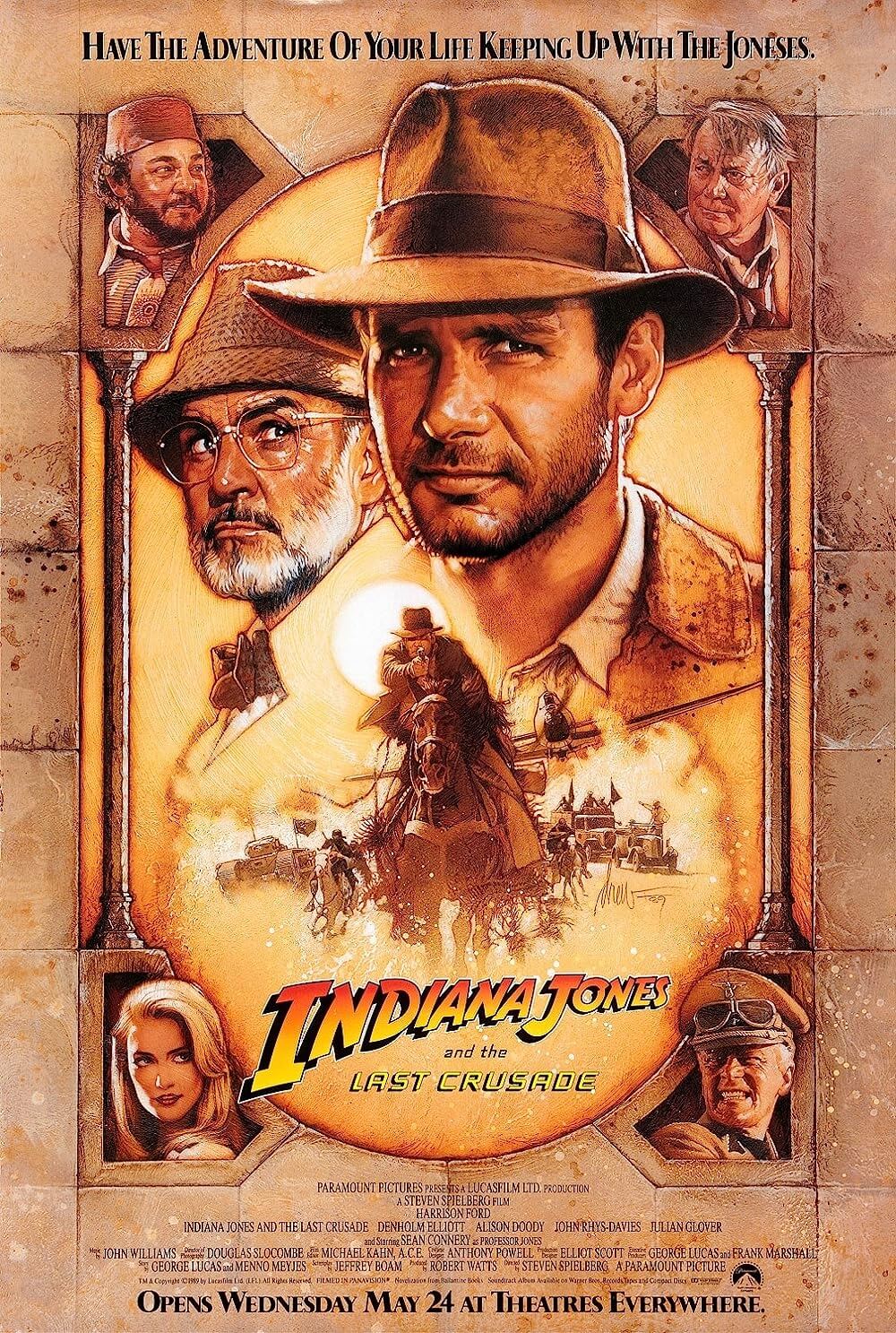

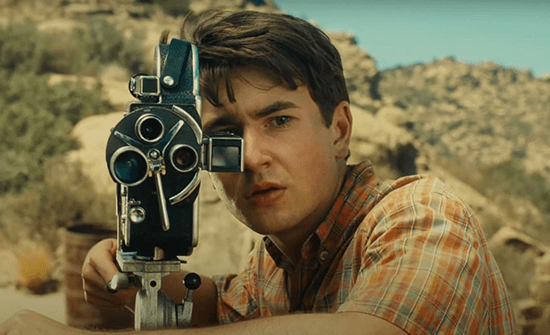

In a sharp transition, The Fabelmans leaps to the teenage version of Sammy (Gabriel LaBelle). In the years between, he has gone from making mummy movies with his sisters wrapped in toilet paper to a Western shot in the Arizona hills with his fellow Boy Scouts—images that recall the opening of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989). Sammy is inspired to make a short film called “Gun Smog” after seeing John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). Burt helps out, yet when he finally sees the film, Sammy’s father is amazed to discover the young director’s ingenuity in poking pin holes in the film stock to create the illusion of a gun flash. His mother and Bennie, of course, are moved by the story. During these teen years, Sammy starts to notice the curious role Bennie plays in their family. He’s a tech whiz, but not nearly as skilled as Burt, and a jokester who constantly makes Mitzi laugh. But there’s something more. The dynamic reveals itself further after a family camping trip, where Bennie tags along, and Sammy records everything. Only when Sammy goes back to cut the footage together does he see what he missed—and he receives an important lesson that nothing can hide from the camera.

For over two decades, Spielberg has shown interest in exploring his childhood on the screen, but he was hesitant to follow through, fearing how his parents would react to seeing their personal lives turned into art for the masses. His real-life parents, Leah and Arnold, have passed in the last few years, giving the director the push he needed to finally share his story. But The Fabelmans doesn’t show a scathing or unloving critique of his upbringing. Instead, it’s at once a tender portrait of his family and an effort to understand the complexity of his parents, including their unstable and sometimes downright volatile relationship. Dano plays Burt as cold and logical, evidenced by the vast, unwelcoming geometry of the eventual California home that takes the family away from Bennie. Burt has love to give, in his way, but his methods are reserved. The showier and more expressive performance belongs to Williams. She captures Mitzi’s artistic impulses and flighty emotionality in several unbridled scenes and amusing details, such as when her long nails click on the piano keys during a recital. The standout is a beautiful and oddly voyeuristic moment when Mitzi dances in front of car headlights one night on the family camping trip. This mesmerizing and loaded scene becomes ever more complex when Sammy revisits the footage. Although Sammy relates to Mitzi’s expressiveness, he also resents her for shattering his rosy perspective about his family.

One of the film’s most affecting scenes comes after Mitzi’s mother dies, prompting a visit from Sammy’s mysterious great uncle, Boris (Judd Hirsch), who regales the family with tales of his life in the circus and silent movies. Boris doesn’t take long to recognize that he and Sammy are “junkies for art.” Hirsch’s screentime barely amounts to 15 minutes, but he leaves a mark with Boris’ speech about how his family will always be secondary to his art: “It’ll tear you in two.” Indeed, at several points in the film, Sammy must reconcile what’s best for his art and what’s best for him. Maybe that’s why, after the Fabelmans move to California, and Sammy is exposed to anti-Semitism for the first time in high school, he resolves to frame his jocular bully Logan (Sam Rechner) as an Adonis-like hero when Sammy puts together the official class “Senior Ditch Day” movie. (His other bully, played by Oakes Fegley, isn’t so lucky.) Afterward, Logan confronts Sammy, and the two reach a kind of understanding, with Sammy promising to keep it a secret. “Unless I make a movie about it,” he adds—a riotous and winking moment of Spielberg’s self-awareness, and not the film’s last. This recalls another moment when Burt asks Sammy to create a sizzle reel of their camping trip for his mother, and Sammy leaves out the clear indicators of a romance between Mitzi and Bennie for his mother’s sake. Later, he cuts together the discarded footage—a cruel compilation that demonstrates how Sammy remains better at communicating through his art than articulating what he’s feeling with words. No wonder, given his upbringing under parents who seldom communicate their feelings.

One of the film’s most affecting scenes comes after Mitzi’s mother dies, prompting a visit from Sammy’s mysterious great uncle, Boris (Judd Hirsch), who regales the family with tales of his life in the circus and silent movies. Boris doesn’t take long to recognize that he and Sammy are “junkies for art.” Hirsch’s screentime barely amounts to 15 minutes, but he leaves a mark with Boris’ speech about how his family will always be secondary to his art: “It’ll tear you in two.” Indeed, at several points in the film, Sammy must reconcile what’s best for his art and what’s best for him. Maybe that’s why, after the Fabelmans move to California, and Sammy is exposed to anti-Semitism for the first time in high school, he resolves to frame his jocular bully Logan (Sam Rechner) as an Adonis-like hero when Sammy puts together the official class “Senior Ditch Day” movie. (His other bully, played by Oakes Fegley, isn’t so lucky.) Afterward, Logan confronts Sammy, and the two reach a kind of understanding, with Sammy promising to keep it a secret. “Unless I make a movie about it,” he adds—a riotous and winking moment of Spielberg’s self-awareness, and not the film’s last. This recalls another moment when Burt asks Sammy to create a sizzle reel of their camping trip for his mother, and Sammy leaves out the clear indicators of a romance between Mitzi and Bennie for his mother’s sake. Later, he cuts together the discarded footage—a cruel compilation that demonstrates how Sammy remains better at communicating through his art than articulating what he’s feeling with words. No wonder, given his upbringing under parents who seldom communicate their feelings.

Much of The Fabelmans unfolds in a familiar coming-of-age structure, especially the later high school scenes. They involve thuggish sportos, Sammy’s Christ-loving girlfriend (Chloe East), and a climactic scene at a school dance—all shot with a similar, albeit smaller-scale bravado as last year’s West Side Story. Spielberg and his regular cinematographer Janusz Kamiński capture commonplace domestic scenes with hints of nostalgia shaped by the sometimes volatile reality of familial discord. But it’s not all showy. A late shot of Burt grappling with Mitzi’s absence, framed against a white, spare interior, is captured with all the existential severity of an Ingmar Bergman composition. Elsewhere, the dazzling sequences of Sammy shooting his short films, including an elaborately mounted World War II drama that echoes Saving Private Ryan (1998), have an infectious energy. When Sammy exhibits them, Spielberg shows Burt nodding in intrigued appreciation. Still, the camera dwells on Mitzi’s enthralled reaction—a career-long technique that finds Spielberg more interested in a spectator’s reaction than the object of a spectacle alone. For Sammy, and therein Spielberg, there’s no reaction more important than his mother’s, at least while their family remains together. Accented by the lovely score by John Williams, these scenes contain magic that only Spielberg could accomplish. There’s also a profound sense of emotional truth throughout, such as how Sammy resents his father for loving his work but doesn’t yet see how his father’s affection for computers is tantamount to his own obsession with filmmaking.

The film’s inclusion of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance early on comes back around in the final scene—a recreation of a story that Spielberg has told many times. Sammy has an encounter with a cantankerous John Ford, hilariously played by David Lynch, who gives the young Hollywood wannabe some sage advice about camera placement before telling him to “get the fuck out of my office!” Whether the account is true or not doesn’t really matter anymore. As one character in Ford’s film resolves, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” The scene is followed by a final visual maneuver that shows the audience what it means to be conscious of framing and visuality—something apparent throughout The Fabelmans and Spielberg’s entire career. While the anecdote and much of the film could be accused of self-aggrandizing its director and printing the legend, that’s precisely what Spielberg does. The director’s knowledge of where to put the camera and how to induce our collective awe demonstrate his enduring skill at creating legendary and timeless onscreen imagery. More than that, The Fabelmans is also funny, moving, superbly acted, and extraordinarily well-executed. For those who don’t know much about Spielberg’s off-screen life or persistent themes involving broken families in his body of work, the film may not be quite a revelation. But for a certain segment attuned to one of this era’s greatest filmmakers, The Fabelmans may be Spielberg’s most heartfelt and personal film to date.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review