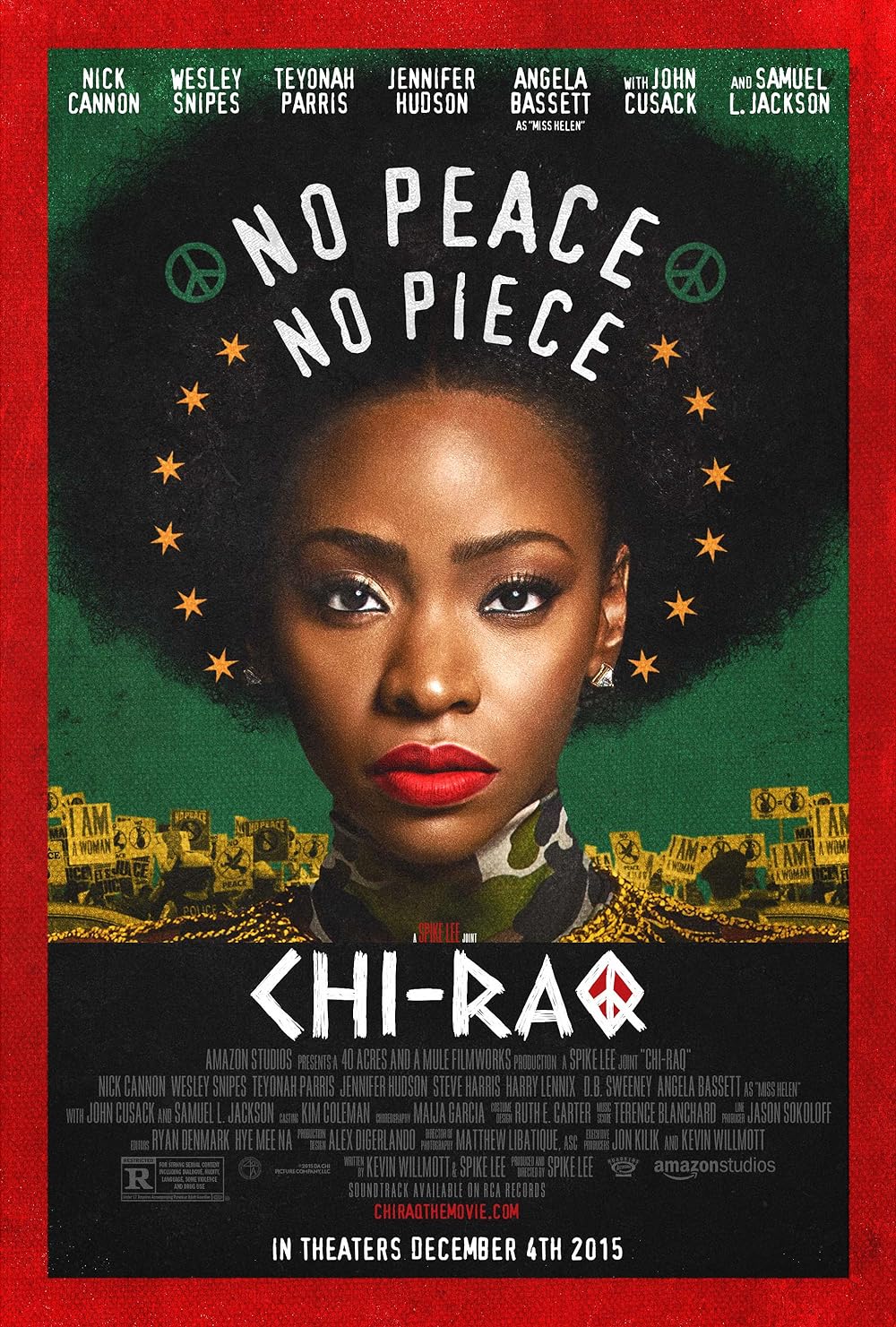

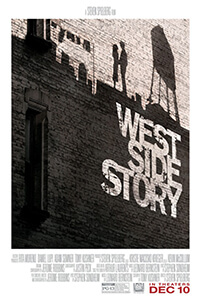

West Side Story

By Brian Eggert |

West Side Story has a place in the canon of great Broadway musicals adapted to the screen. First performed in 1957 on stage and made into an iconic motion picture in 1961, the material blends highbrow and lowbrow, repackaging Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet into a commentary on racial intolerance through the then-prevalent epidemic of street violence among juvenile gangs. Leonard Bernstein’s music, Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics, Arthur Laurents’ book, and Jerome Robbins’ choreography combine into a cherished, archetypal musical, where shifts in tone prove erratic but thrillingly unpredictable. The story, about a gang of Irish kids warring with a group of Puerto Ricans, and the two lovers, one from either side, caught in the middle, has been praised for its focus on Latinx characters (most of them played by white actors) and criticized for racial stereotypes. Yet, wherever you come down on West Side Story, there’s no denying that it’s been a cultural landmark for more than half a century, inspiring countless revivals (and cringe-worthy high school productions). So, given its well-established legacy, why would a filmmaker like Steven Spielberg want to remake it?

The result, a profoundly well-directed film, boasts revised choreography by Justin Peck and an updated screenplay by Tony Kushner, who wrote Munich (2005) and Lincoln (2012) for Spielberg. The new version keeps the songs intact but amends many aspects of Robert Wise’s 1961 film that haven’t aged well. For instance, Spielberg casts Latinx performers in the appropriate roles and forgoes the original’s brownface. There’s also a greater focus on diverse Puerto Rican representation, complete with long patches of dialogue in Spanish—and refreshingly, without subtitles (not that non-Spanish-speakers will require them; the context is clear). Additionally, Kushner develops xenophobia into an active theme and holds bigots accountable, whereas socially undesirable behavior in Wise’s film went mostly unchecked. To be sure, the new film reveals undercurrents that would have made the original too political or controversial in 1961—Wise’s film, after all, is best remembered for its singing, dancing, and production design. But, 60 years later, these necessary conversations about race and representation don’t have to feel so half-hearted.

The film’s first shots signal gentrification underway in the titular neighborhood, where the bodegas that once replaced the Irish pubs will soon meet with a wrecking ball. The Jets, led by the wiry Riff (Mike Faist) who is angry at anyone who doesn’t look like him, gather paint cans to deface wall art of the Puerto Rican flag. The Sharks, led by boxer Bernardo (David Alvarez), catch them in the act. There’s a brawl and a chase, at which point Officer Krupke (Brian D’Arcy James) and Lieutenant Schrank (Corey Stoll) appear to explain that soon enough, they’ll all be evicted, regardless of their ethnicity. The Jets, products of abusive fathers and neglectful mothers are “the last of the can’t-make-it Caucasians,” Schrank explains. Despite living in New York, the melting pot of all melting pots, these groups want to destroy each other. Spielberg’s film underlines how the Jets remain the aggressors of racial bigotry, with Riff silencing dissenters who question the logic of intolerance given that Puerto Rico is, technically, part of America. The Puerto Ricans, meanwhile, sought America’s promise of freedom and opportunity only to realize the reality: “Life is all right in America, If you’re all white in America.”

What seemed trivially handled in Wise’s version feels searing and complex in Spielberg’s hands. Just as Wise did, Spielberg shoots scenes in actual exterior locations, using CGI to paint over the modern cityscape in the background. But Spielberg’s take feels grittier, set among crumbling buildings and rubble. The streets and alleyways look busier, filthier, like spaces where people live instead of Wise’s locations that seemed emptied to service the production. Spielberg recognizes that West Side Story is a film about star-crossed lovers Tony and María, played by Ansel Elgort (Divergent, Baby Driver) and Rachel Zegler, who makes her film debut. Even so, his film’s portrayal of racial intolerance, multiple murders, and attempted rape feel more urgent—and production designer Adam Stockhausen’s treatment of the surroundings reflects that. Spielberg’s world of griminess also features brutal violence. The paint-bucket-to-head fights between the two gangs leave a mark (or a nail through the ear). And the violence doesn’t look like old-fashioned movie violence; it looks like it hurts and kills.

What seemed trivially handled in Wise’s version feels searing and complex in Spielberg’s hands. Just as Wise did, Spielberg shoots scenes in actual exterior locations, using CGI to paint over the modern cityscape in the background. But Spielberg’s take feels grittier, set among crumbling buildings and rubble. The streets and alleyways look busier, filthier, like spaces where people live instead of Wise’s locations that seemed emptied to service the production. Spielberg recognizes that West Side Story is a film about star-crossed lovers Tony and María, played by Ansel Elgort (Divergent, Baby Driver) and Rachel Zegler, who makes her film debut. Even so, his film’s portrayal of racial intolerance, multiple murders, and attempted rape feel more urgent—and production designer Adam Stockhausen’s treatment of the surroundings reflects that. Spielberg’s world of griminess also features brutal violence. The paint-bucket-to-head fights between the two gangs leave a mark (or a nail through the ear). And the violence doesn’t look like old-fashioned movie violence; it looks like it hurts and kills.

Still, Spielberg embraces West Side Story’s awkward shifts in tone, customary for musicals, meaning audiences witness the two gang leaders murdered in one scene, then transition from grave seriousness to María’s airy “I Feel Pretty” in the next. That’s part of the fun, I suppose. Although Spielberg has never made a musical, watching the film brings to mind his incredible dance-turned-brawl sequence from 1941 (1979), and his organization of screen chaos has rarely been better since. He replicates something similar during the community’s “social experiment” dance designed to bring the combative sides together. The camera enters the dance hall, glides over dozens of dancers, and turns to regard the action from the other side as though Janusz Kamiński’s camera has wings. Indeed, Spielberg’s near-flawless control of the cinematic apparatus throughout results in a wellspring of stunning imagery, such as when the gangs meet for their showdown, and their long shadows extend across the floor and intertwine. It’s a downright beautiful film, but more often than not, I found myself appreciating the choreography and cinematography more than the substance of the narrative.

Even as Spielberg manages the basic requirements of a movie musical, complete with spectacle and visual splendor aplenty, his film doesn’t correct some of the fundamental issues with the source material. Despite its origins in the greatest romantic tragedy ever told, Tony and María have never been that interesting. Kushner’s screenplay may inch toward realism, but it doesn’t resolve how Tony and María fall in love after one meeting like in an old movie. It’s what keeps this critic from loving the original film and Spielberg’s new one. And just as the original’s Natalie Wood and Richard Beymer had no chemistry, the least convincing aspect of the film remains the two leads, who become its not-quite-fatal flaw. Zegler may have worked with another performer, but Elgort looks too polished next to his fellow Jets. He has the appearance of an actor reprising his role from his high-school production and not like a character who has been to jail or seen “trouble.” In a film populated by mostly unknown performers, his presence distracts, offering little expressivity or rage. The one exception is Elgort’s reaction when Anita (Ariana DeBose, ever a scene-stealer), getting revenge for Tony’s killing of Bernardo, lies and tells him María has died—the look of terror and heartbreak is genuinely unhinged. Of course, Spielberg’s West Side Story stops short of giving María the same fate as Juliet, which has always felt wrong somehow.

At 156 minutes, West Side Story moves at a brisk pace and improves on the original, which, I know, may sound like blasphemy to some. Although it would be a stretch to call the new film necessary, it demonstrates how a director who takes another pass at established material, especially in the case of a Broadway musical or stage play, can work out some of the kinks—but in this case, not all of them. Spielberg’s urgency, Kushner’s sharper and slightly more socially aware screenplay, and the dazzling individual song sequences work wonders, even as all of the dancing and singing seem to contrast the story’s tragic subject matter. But the film’s standout is DeBose as Anita, the exact role played by Rita Moreno in Robert Wise’s original film (Moreno also appears as Valentina, the wise sage who runs the local pharmacy). DeBose electrifies; she commands the screen whenever she appears, conveying Anita’s energy and passion. A performance like this makes us question why Anita and Bernardo aren’t the leads and naggingly reminds us that Tony and María are dull by comparison. There are some things not even Spielberg can improve.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review