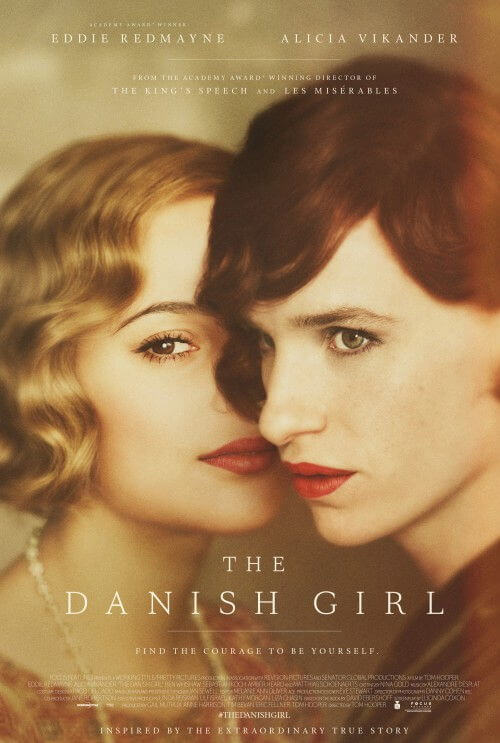

The Danish Girl

By Brian Eggert |

A portrait of a bohemian marriage and a transgender awakening, The Danish Girl is a film with something to say about surfaces and the truths beneath them. That message isn’t always clear thanks to director Tom Hooper (The King’s Speech, Les Misérables), who approaches the subject with utter care, relying on an elaborate formal style of wide-angle lenses, decorative interiors, and mannered performances, but also emotional distance. Alicia Vikander and Eddie Redmayne play Gerda and Einar Wegener, both painters in Copenhagen in the 1920s. Inside of Einar resides Lili Elbe, Einar’s deeply hidden female persona. The script by Lucinda Coxon was based on David Ebershoff’s 2000 novel of the same name, a fictionalized biography of Lili Elbe. Lili was one of the first people to try sexual reassignment surgery, and the physically taxing result left her with only moments of life to feel complete.

Living in a modest apartment, the painting couple seems incredibly happy and sexually alive in the initial scenes. Gerda works on her portraits, while Einar labors over landscapes. When a model fails to show up for a sitting, Gerda asks her husband to wear stockings and hold a dress over himself to assist in her finishing a piece. The moment feels comfortable for Einar, who proceeds to almost fetishize stockings and wear his wife’s nightie under his clothes. As a joke, Gerda dresses up the willing Einar as a woman to attend the local artists’ ball, and he attends under the faux identity of his cousin Lili. Only when a male suitor (Ben Whishaw) approaches does Lili, who has been there since Einar was a boy, come alive and begin to demand life. Through a process Lili herself describes through terms of death and rebirth, she and Gerda, who feels understandably conflicted about losing her husband, proceed to explore the possibility of a sex change.

Along with Alexandre Desplat’s forced score, Hooper’s treatment distances the audience from the subject matter. There’s an ornate quality to every shot, as though he and cinematographer Danny Cohen designed every frame to resemble one of Gerda’s paintings—filmed from painterly angles and with earthy, atmospheric colors taken from the Copenhagen seaside. This un-reality to the proceedings distances us from the emotional reality of Einar’s awakening into Lili, as does Redmayne’s forced and oozing performance (his portrayal is only about one bar less excessive than his villain role in Jupiter Ascending). Fraught with heavy blinks, breathy speech, affected mannerisms, and an uncomfortable smile that’s painful to watch, Redmayne’s performance turns the reality of Lili’s real-life journey into theater.

Rather than openly discuss how Lili feels trapped inside Einar’s body and create a dialogue about her incongruous balance between body and mind, the film chooses to represent that in ways that are more about technique. Redmayne shows us the physical differences in the way Lili and Einar walk and talk, how Lili carries herself with her chin down, her neck arched, her hands and wrist bending in mannered feminine pose—again, like one of Gerda’s paintings. Redmayne’s performance is labored over, which might be understandable if he chose to represent Einar as an act, but the Lili character emphasizes more than once that Einar is dying and Lili has been allowed to live. Nevertheless, Lili never comes alive, just as Hooper’s direction feels formally intentional in every shot.

By contrast, we feel every emotion in Vikander’s natural performance; however, her realness is almost out of place in a film that’s so much about surfaces. Vikander’s playful and raw performance as Gerda is the best thing about The Danish Girl. She’s had a stellar year in 2015, beginning with Ex Machina and carrying into The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Burnt (the less said about Seventh Son the better). But Vikander’s emotional reality also tips the audience to her perspective, even though the film isn’t solely “about” Gerda. Redmayne simply doesn’t have the same impact on the viewer. In a way, that’s the fault of the script, which has designed Gerda as an entry point for the audience—an historically inaccurate one, since Gerda’s most famous painting subject was lesbian erotica, yet the film chooses to depict her as purely heterosexual.

The Danish Girl is about eradicating surfaces and finding the truth underneath; and yet, to the contrary, Lili is brought to life through Gerda’s paintings—a process of building on a canvas. There’s a carefully played scene where Einar stands in front of a mirror naked, tucks his penis between his legs to create the appearance of a feminine pubic delta, and tears fill his eyes. This scene could have been the moment where the audience finally sees Lili as she should be. But instead, Redmayne and Hooper have left the viewer to imagine Lili’s thoughts and feelings, experiencing Lili’s trapped state through Redmayne’s overly stylized performance. The metaphor that the formation of transgender sexual identity is a portrait waiting to be painted seems wrong somehow, as painting is an individual interpretation, whereas sexuality is innate. By trying to link Lili’s experiences to the metaphor of painting, Hooper has over-thought his film and unintentionally distanced his audience from relating to the material.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review