The Beast

By Brian Eggert |

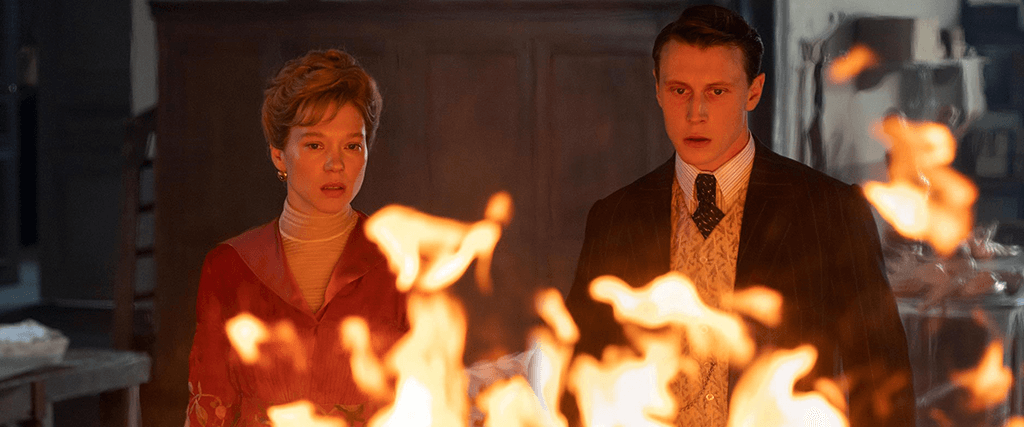

Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast opens inside a green screen void. Later, effects wizards will fill the space with computer-generated images. But for the moment, it’s a negative arena inhabited by Gabrielle, played by Léa Seydoux, an aspiring actress in a Hollywood movie. Gabrielle’s director instructs her to portray fear about something uncanny looming over her. During the scene, she loses herself in the performance; a look of uncertain terror grows in her eyes. She takes hold of the sole prop, a kitchen knife, and screams as though ushering the digital blur into the next scene, set in 1910. From this unsettling, claustrophobic opening, the French filmmaker establishes an equivocal framework that signals the sprawling enigma to come. Bonello’s film leaps from the modern first scene into a triptych spanning three periods, each beset by catastrophes or the fear thereof. In its portrait of three similar relationships, the film alternates among several genres and considers their perceived social, psychological, and technological boundaries, which we use as excuses to avoid making connections. Spanning more than a century in its narrative structure, Bonello’s film confronts how people deny love by avoiding emotional risks and clinging to illusions of control. The Beast is a mesmerizing examination of our reluctance to open ourselves up to vulnerability and authentic experiences, as well as the barriers we establish out of self-preservation.

Bonello based his screenplay on The Beast in the Jungle, Henry James’ 1903 novella about John, a man whose unsupported belief that some imperceptible threat, which he describes as a beast, will befall him. His certainty prevents him from committing to Mary, a woman who loves him. But it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy; John’s irrational sense that some unknown encapsulation of his fate will eventually arrive eats away at his life, wasting it, which becomes the disaster he feared. In freely adapting the famous text, Bonello swapped the protagonist’s gender from male to female and introduced the time-hopping arrangement reminiscent of Cloud Atlas (2012), hinting at a series of reincarnations involving Seydoux’s Gabrielle and her romantic orbit around Louis (George MacKay). Chronologically, the stories take place in 1910, culminating with the Great Flood of Paris; in the Los Angeles of 2014, where Bonello draws from Elliot Rodger, a real-life incel who went on a killing spree in 2014; and in the future Paris of 2044, a world where people purify their emotions by purging past traumas. Each epoch features Gabrielle incapable of communicating her anxieties because they’re “too horrible” to articulate, speaking to the universality of James’ story.

Bonello’s film offers the same warning against being too cautious, but how he turns James’ themes into unclassifiable cinema makes The Beast an absolute marvel. Searching for an unknowable quality in his star, the director cast Seydoux, whom he cast in a small role in his 2008 feature On War. Bonello was convinced that only Seydoux could fulfill Gabrielle’s identities in all their forms, from an intelligent pianist to an obscure object of Louis’ desire, from a floundering model-turned-actress to a doll-like figure. The director even delayed his production a year to accommodate Seydoux’s schedule, convinced no one else could embody his Gabrielles—whether they are separate characters or simply facets of the same person over time. Watching the film, it’s easy to see why Bonello waited. Few performers can so effortlessly transition from the distant past to the present to the future—Cate Blanchett, Juliette Binoche, Gong Li, and Kate Winslet come to mind. Seydoux personifies this timelessness, with a hypnotic quality that preserves her mystery across the film’s periods. And she does wonders with her roles in The Beast. In the press notes, Bonello calls his film “the portrait of a woman that almost turns into a documentary about an actress,” referring to Seydoux, who spends so much time onscreen that some sort of transcendence occurs between actor and character.

Bonello’s film offers the same warning against being too cautious, but how he turns James’ themes into unclassifiable cinema makes The Beast an absolute marvel. Searching for an unknowable quality in his star, the director cast Seydoux, whom he cast in a small role in his 2008 feature On War. Bonello was convinced that only Seydoux could fulfill Gabrielle’s identities in all their forms, from an intelligent pianist to an obscure object of Louis’ desire, from a floundering model-turned-actress to a doll-like figure. The director even delayed his production a year to accommodate Seydoux’s schedule, convinced no one else could embody his Gabrielles—whether they are separate characters or simply facets of the same person over time. Watching the film, it’s easy to see why Bonello waited. Few performers can so effortlessly transition from the distant past to the present to the future—Cate Blanchett, Juliette Binoche, Gong Li, and Kate Winslet come to mind. Seydoux personifies this timelessness, with a hypnotic quality that preserves her mystery across the film’s periods. And she does wonders with her roles in The Beast. In the press notes, Bonello calls his film “the portrait of a woman that almost turns into a documentary about an actress,” referring to Seydoux, who spends so much time onscreen that some sort of transcendence occurs between actor and character.

After the green screen prologue, Bonello leaps back to 1910 with a stark shift in time designed to prepare the viewer for similar transitions throughout the film. The initial change alerts viewers to sit up in their seats and expect the unexpected for the remainder of the film, and Bonello doesn’t disappoint. For the 1910 scenes, the director insisted on shooting with 35mm alongside cinematographer Josée Deshaies, his collaborator going back to The Pornographer (2001), and they captured sumptuous images reminiscent of Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993). The scenes in 1910 center on Gabrielle Monnier, a renowned pianist now struggling to master a piece by Arnold Schoenberg. At a party, she runs into an Englishman named Louis (MacKay), whom she met years ago in Naples where she confessed her fear that some manner of beast would be her fate. While “mixing tongues” between French and English—a loaded metaphor to be sure—she once again bonds with Louis about her sense of doom. The two have a tenuous and unrealized romance, marked by social decorum and Gabrielle’s pressing terror, and they remain on the verge until rising waters from the Seine undo their world.

Another stark shift brings the viewer to 2044, where excess and waste have been neutralized, leaving the era a spare and empty world, which Bonello captures in an efficient Academy ratio—at once austere and somehow limited. It’s a future where automobiles, billboards, and even people seem conspicuously absent from the surroundings, and nightclubs only engage in excess as a nostalgic treat, such as a club based on the year 1972. Gabrielle interviews for a job during this period, but her “affects” or emotions impact her chances. In a plot detail similar to the erasure of memories in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), people in this future purify themselves of emotions to remove excesses and achieve “clean DNA.” Gabrielle reluctantly visits a purification center to cleanse herself, even though she doesn’t feel that her emotions are impure. She worries about the consequences of the process, which involves lying in a black ooze—reminiscent of Baron Harkonnen’s detoxifying baths in the Dune series—and enduring a robotic needle in the ear. Also drawn to a Louis in this era, the last thing Gabrielle wants is to become another emotionless entity; AI and cold, impersonal interactions already consume enough in her world. Regardless, she keeps attending sessions, and because she remains triggered by images of her past lives, the process doesn’t stick.

In the middle of these two periods is a story set in 2014, where MacKay plays another Louis based on Elliot Rodger, who uploaded several videos to YouTube and declared his hatred for all women who reject him before going on a rampage that left six dead. During this period, Louis inhabits his safe world on social media by recording videos in which he describes himself as “magnificent” and “the ultimate gentleman.” Frustrated by the presence of couples in love, he’s determined to “show the world why life isn’t fair.” Bonello drew much of the dialogue in these scenes directly from Rodger’s original videos, adding a disturbing real-world undercurrent to MacKay’s performance. Louis is drawn to Gabrielle, who hopes to become a model and actress. House-sitting at a lavish residence in Los Angeles, a city often said to be difficult for its loneliness, Gabrielle yearns to make a connection. She wanders from auditions to nightclubs for company, but she ends up back at home. Scouring the internet, she visits a psychic’s website for a far-from-reassuring video chat, where the clairvoyant expresses fear for Gabrielle’s safety. Does the psychic’s feeling refer to the earthquake that occurs or the looming threat of Louis, who has been stalking Gabrielle? Either way, both Louis and Gabrielle in 2014 feel more connected by online worlds that alienate them, offering a sharp critique of the internet and social media.

In the middle of these two periods is a story set in 2014, where MacKay plays another Louis based on Elliot Rodger, who uploaded several videos to YouTube and declared his hatred for all women who reject him before going on a rampage that left six dead. During this period, Louis inhabits his safe world on social media by recording videos in which he describes himself as “magnificent” and “the ultimate gentleman.” Frustrated by the presence of couples in love, he’s determined to “show the world why life isn’t fair.” Bonello drew much of the dialogue in these scenes directly from Rodger’s original videos, adding a disturbing real-world undercurrent to MacKay’s performance. Louis is drawn to Gabrielle, who hopes to become a model and actress. House-sitting at a lavish residence in Los Angeles, a city often said to be difficult for its loneliness, Gabrielle yearns to make a connection. She wanders from auditions to nightclubs for company, but she ends up back at home. Scouring the internet, she visits a psychic’s website for a far-from-reassuring video chat, where the clairvoyant expresses fear for Gabrielle’s safety. Does the psychic’s feeling refer to the earthquake that occurs or the looming threat of Louis, who has been stalking Gabrielle? Either way, both Louis and Gabrielle in 2014 feel more connected by online worlds that alienate them, offering a sharp critique of the internet and social media.

Across these timelines, Bonello explores new genres and locations in his body of work. The 1910 setting may be familiar to the director, who made a costume drama about a Parisian brothel with House of Tolerance (2011). But the 2044 sequences feel like something altogether new in his filmography, conceived by Bonello and production designer Katia Wyszkop with minimalist futurology that looks as though Bonello simply reduced visual stimuli rather than added elaborate new technologies, outlandish costumes, and architecture. By contrast, the sequence in 2014 finds Bonello exploring the thriller genre, with hints of David Lynch’s two a-woman-in-trouble-in-Los-Angeles features, Mulholland Drive (2001) and Inland Empire (2006). Though, Bonello has said his primary reference point was When a Stranger Calls (1979). He implants a nerve-racking threat with the presence of Louis’ gun and the impending home invasion, prompted by Louis’ horrifying declaration that “today is the day of retribution.” And yet, the director also conjures a maddening, indistinct terror from Gabrielle’s incidental, disorienting experiences, such as stepping on a bloody dead bird in the driveway. And when her late-night web visit leads to a rampant influx of pop-up ads and videos—among them, images from Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers (2009)—the effect is somehow even more jarring.

Bonello and editor Anita Roth move freely between the three periods during the film’s two-and-a-half-hour runtime, focusing mainly on the 1910 story in the film’s first half and the 2014 story in the second. Both represent memories that Gabrielle in 2044 attempts to purge. Bonello presents them with a characteristic loose style and aesthetic freedom, indulging in delirious club sequences one moment and a montage of black-and-white photos from the 1910 flood the next. The one constant is that something unknown plagues each Gabrielle, but should she choose the safe option of bonding with an artificial person such as Kelly (Guslagie Malanda)—whose “Poupée” designation literally means “doll” in French—in the 2044 setting? Or should she risk emotional spontaneity by leaping into a bond with another individual who may have facets she may never understand? Most curious is Bonello’s willingness to understand the 2014 version of Louis, who seems to suffer from a fear of love, which he processes into a volatile relationship with women. After an earthquake in L.A., Gabrielle asks him to walk her home. Her attention might suggest that she’s interested in him, which she is, yet he refuses the opportunity out of the safety net of alienation. “I’m afraid I’d do something stupid,” he admits. The Beast becomes a commentary on a strain of emotional risk avoidance, amplified by the internet and social media, that has left our culture connection-averse.

Several recurring themes and symbols appear in the three periods, raising questions about what they signify. Each period features a looming disaster, a dreaded pigeon, and dancing, giving viewers plenty of parallels and symbols to interpret next to the film’s central theme—a cautionary tale about not reserving your love or authentic self out of fear, and instead embracing expressive actions. The most prominent theme is dolls. In 1910, Gabrielle’s husband runs a small factory that makes hand-crafted ceramic and celluloid dolls. The new celluloid models are flammable but with an appealing softness to the touch that distinguishes them, leading to a sequence involving a disastrous fire and underwater swim, both presented in a tactile contrast to the VFX prepared in the film’s first green screen sequence. In 2014, Louis sees women as inhuman dolls, whereas the 2044 timeline features Kelly as an AI robot, a kind of living doll to which Malanda gives an uncanny presence. But Gabrielle wants to avoid becoming another empty shell of a person who is no different than an automaton in the future setting. She looks at Kelly and declares, “You bore me.” Bonello critiques those who would live as an empty, inexpressive shell with a doll face designed to be neutral—“Not too emotional, so it will please everyone,” says Gabrielle’s dollmaker husband.

Several recurring themes and symbols appear in the three periods, raising questions about what they signify. Each period features a looming disaster, a dreaded pigeon, and dancing, giving viewers plenty of parallels and symbols to interpret next to the film’s central theme—a cautionary tale about not reserving your love or authentic self out of fear, and instead embracing expressive actions. The most prominent theme is dolls. In 1910, Gabrielle’s husband runs a small factory that makes hand-crafted ceramic and celluloid dolls. The new celluloid models are flammable but with an appealing softness to the touch that distinguishes them, leading to a sequence involving a disastrous fire and underwater swim, both presented in a tactile contrast to the VFX prepared in the film’s first green screen sequence. In 2014, Louis sees women as inhuman dolls, whereas the 2044 timeline features Kelly as an AI robot, a kind of living doll to which Malanda gives an uncanny presence. But Gabrielle wants to avoid becoming another empty shell of a person who is no different than an automaton in the future setting. She looks at Kelly and declares, “You bore me.” Bonello critiques those who would live as an empty, inexpressive shell with a doll face designed to be neutral—“Not too emotional, so it will please everyone,” says Gabrielle’s dollmaker husband.

The Beast features a staggering moment when Seydoux acts out a doll’s expression, and while Bonello holds the extended shot, the enigmatic performer’s face becomes increasingly empty and even creepy, devoid of any feeling. Every person has the potential to love or a similar potential to shut themselves off from love—though without love, we may as well be empty dolls. The Beast offers repeated warnings against hiding from love and reality, and the lesson extends to filmmaking as well. Many of today’s filmmakers avoid reality because digital solutions prove easier, leaving so much accomplished on green screens and processed through servers before becoming a completed work. The outcome is not a literal film but a digital file, and often, its CGI creations ring false—hollow and unconvincing replications of reality. For Bonello, this represents a fear of the unknown, a suppression of the controlled chaos inherent to filmmaking that digital confections circumvent. He yearns for more genuine, authentic expressions in cinema and blends classical celluloid filmmaking with modern digital methods to convey how cinema can still feel alive, even in a modern format. At the same time, Bonello proves skeptical about love and relationships in our increasingly artificial world, given the omnipresent need to control life out of fear of exposing oneself to emotional risk. To those ends, The Beast is a haunting, enthralling, yet oddly reassuring experience. Even as it transfixes and sometimes confounds, it offers a passionate meditation on how to live.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review