One Battle After Another

By Brian Eggert |

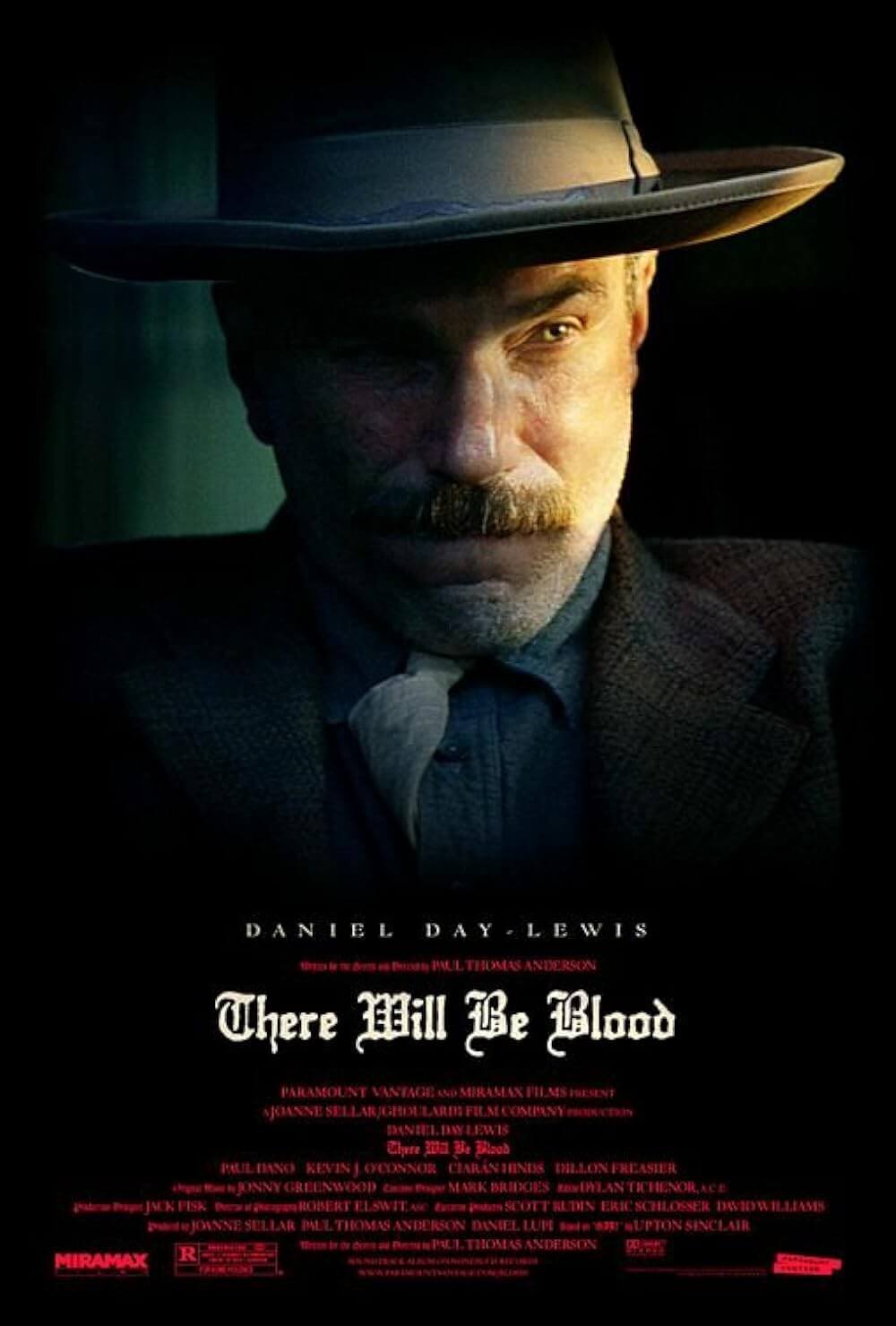

One Battle After Another opens with “the announcement of a motherfuckin’ revolution” by a group known as the French 75. They liberate immigration camps, bomb government offices that support unjust policies, and rob banks to fund their missions. Their dissent against the steadily more fascistic establishment has simmered for years. How telling and reflective of America’s continued infighting that writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson adapted Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel Vineland and gave the material a new skin for our times. Yet, the scenario feels no less relevant for its origins as a takedown of Reagan-era politics. The American culture war has been raging since its inception, and even while exploring that conflict and its consequences, Anderson delivers a galvanizing blend of high and low extremes: the film is his most urgent and political to date (even more than There Will Be Blood, 2007), albeit imbued with a humanity and unlikely humor that just so happens to be fun and exciting to watch. It’s an action movie collision between desperate extremists and zealous state oppressors. With a sprawling runtime and terrific ensemble cast, One Battle After Another feels at once epic and personal in Anderson’s portrait of America’s inward-facing bitterness and the accompanying human toll.

Anderson sets the story in motion with Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), a raging French 75 militant determined to set ablaze capitalist institutions that would imprison—both literally and figuratively—those marginalized in American society: anyone not fitting the white cisgender male archetype. Lighting her fuse is Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio), nicknamed “Ghetto Pat,” a demolitions expert who, in the first scenes, creates a pyrotechnic distraction as their group rescues dozens of immigrants from a detention center. During the fracas, Perfidia encounters Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn), a staunch military man and fanatical racist who, even while vowing revenge on Perfidia for humiliating him, nonetheless shares with her a mutual attraction. Each is the other’s obscure object of desire. Soon, Bob and Perfidia have a child together, but she remains defiantly self-involved, to the point that she loses respect for Bob’s willingness to settle down and raise Willa, their daughter. “I put myself first,” she declares. Inevitably, Lockjaw’s forces swoop in and dismantle much of the French 75, leaving the survivors to scatter. Captured, Perfidia goes into witness protection, only to disappear before testifying.

Sixteen years later, Bob and Willa (Chase Infiniti) live in an isolated home near Baktan Cross, a sanctuary city populated by immigrant workers who thrive thanks to the town’s integrated underground. When Lockjaw targets the city, he does so in the hope of capturing Perfidia’s daughter, believing he may be the father. Lockjaw’s agents invade local schools and businesses, but a French 75 rebel (Regina Hall) has already fled with Willa and plans to rendezvous with her father. One problem: Bob has spent the last decade and a half getting stoned and drunk, forgetting the passwords and elaborate codes he was charged with remembering in case this very situation arose. “Ghetto Pat” now casually watches The Battle of Algiers (1966) and smokes a roach while trying to remember the phrase that will unlock his daughter’s secret location. It’s among the funniest scenes in the film, with Bob trying to reason with and inevitably blowing up at the French 75’s fussy, by-the-book operator. In a frantic race to find Willa, Bob scrambles to find a charger for his dead phone amid the assault on Baktan Cross. And Willa’s sensei Sergio (Benicio del Toro), from the resident martial arts school, whose “no fear” attitude renders him delightfully cool as a cucumber even in the tensest situations, helps Bob along.

Lockjaw’s mission is both personal and ideological. He’s under review for acceptance into an elite underground white-supremacist order, ridiculously named the Christmas Adventurers Club, whose members greet each other with “Hail Saint Nick” and work in the shadows toward “racial purification” by disposing of the “dangerous lunatics, haters, and punk trash” of the world. In his twitchy ball-of-rage performance, Penn recalls Sterling Hayden in Dr. Strangelove (1963), whose warped ideas and psychosexual anxieties combined into a nasty and volatile human concoction. Penn’s leathery skin and wired physique make him visibly unstable, with his flushed neck looking like a cartoon character who’s boiling and about to steam from his ears. This is a long way from Jeff Spicoli. He’s the most pronounced military caricature in the film, accompanied by others with names such as Skinner and Toejam—not codenames, but actual surnames. Lockjaw becomes ever more dangerous when he targets Willa, who believes her mother is dead and doesn’t know that the French 75 consider her a rat. Lockjaw remains intent on disposing of her should he discover, with his travel-size DNA kit, that he’s Willa’s biological father. With her alive, he can’t become a Christmas Adventurer; one of their entry requirements precludes any relationships or history of sexual encounters with people of color.

Anderson’s loose adaptation of Pynchon’s novel changes character names and settings, updating the material for today’s America, where ICE goons hold brown people in caged detention centers and barely hide their white supremacist ambitions. One Battle After Another is bound to piss some people off, in particular one sequence where Lockjaw’s squad orders one of their own to throw a Molotov cocktail from within the ranks of peaceful protesters, justifying the soldiers’ violent response. Say what you will about studios capitulating to this administration’s pressure to limit critiques of hate groups; with this and Sinners, Warner Bros. has released two politically charged, original films by major auteurs this year, both of which censure American racism, and both with budgets of around $100 million. That level of risk-taking should be celebrated, and its not without precedent: While most studios curbed their anti-fascist rhetoric in the late 1930s and early 1940s before the United States entered World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Warner Bros. was among the only studios to actively condemn Hitlerism and fascism in their firebrand output, such as The Black Legion (1937) and Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939).

Much like another filmmaker from that era, Charlie Chaplin, who so effectively skewered Hitler with his satire The Great Dictator (1940), Anderson’s portrait of the fascist cabal dabbles in lampoonery. No wonder he casts Kevin Tighe, the villain in so many ’80s action movies and one of the union busters in Matewan (1984), alongside former SNL writer and Billy Madison (1995) star Jim Downey, as members of the Christmas Adventurers Club. Of course, Lockjaw remains the goofiest of them all—he might even be an absurdist character if he weren’t also a frightening, self-hating slab. DiCaprio offers the more comic performance, initially playing an out-of-his-depth rebel who follows in Perfidia’s wake, and then becoming rather endearing as a protective, burnout father whose sudden reactivation into a revolutionary group makes for priceless slapstick comedy. Channeling a similar physicality he displayed in The Wolf of Wall Street (2015)—just replace the cocaine with pot—DiCaprio plays Bob like Jeff Lebowski but with a purpose, donning a plaid flannel robe and shoplifted sunglasses for a slacker militant look throughout the chaos in the second half.

Anderson’s filmmaking, as expected, is nothing short of miraculous in its organization of sweeping events and clarity amid the tumult. Working with cinematographer Michael Bauman and editor Andy Jurgensen, Anderson seldom draws attention to his presence with the level of conspicuous camerawork found in his earlier features, Boogie Nights (1997) and Magnolia (1999). Instead, he employs an immersive and cohesive visual grammar to amplify our emotional involvement in the proceedings, shooting on VistaVision cameras for that deliciously textured, throwback look of real celluloid. Even at the height of the film’s pandemonium, Anderson maintains a spatial awareness with fluid camera movements that follow the action through cramped apartment buildings and down city streets teeming with protesters and soldiers. In the final stretch, he builds a breathless chase on a hilly highway with a camera mounted on the front of a car, producing a phantom sensation of ascending and descending, like we’re on a rollercoaster. Indeed, the film is a ride—clocking in at 162 minutes, its relentless pacing doesn’t let up until the hopeful coda, which is both heartrending and a commentary on how the next generation must keep up the fight.

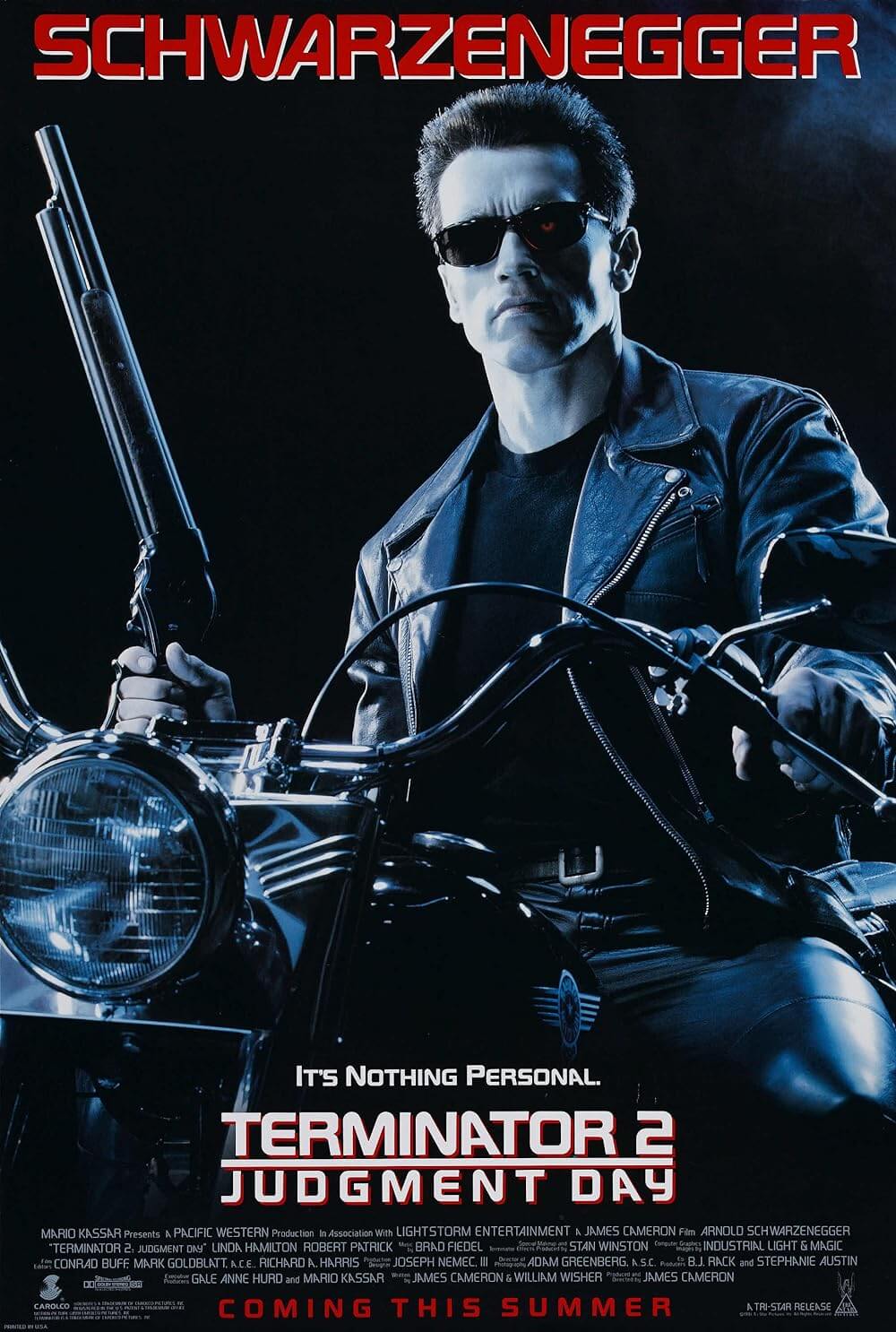

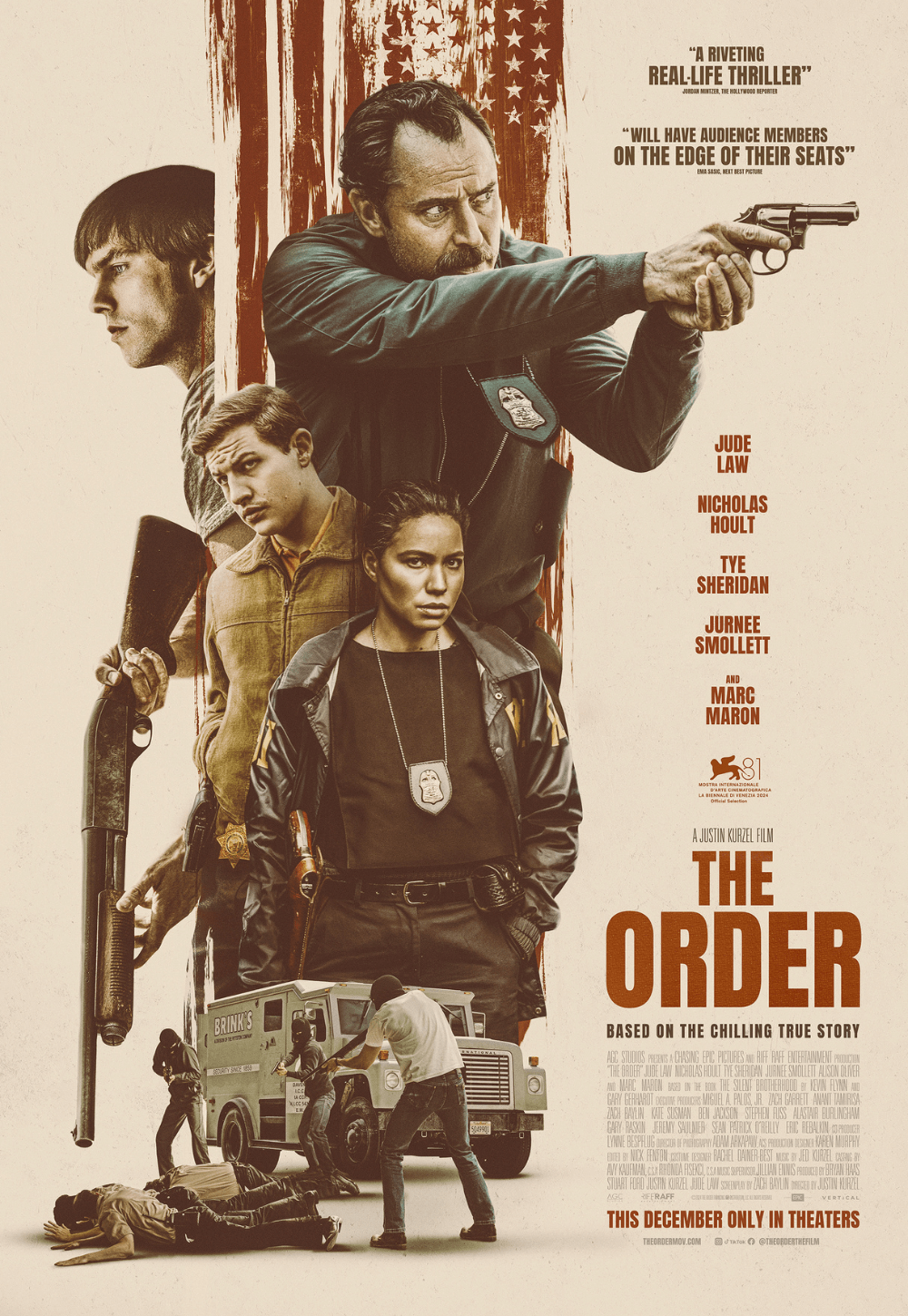

One Battle After Another finds the director in a unique action movie mode, delivering a film with momentum unlike anything he’s made before. After the 16-year leap, the narrative thrust never subsides, recalling the way James Cameron’s films build before setting into motion a nonstop series of action set pieces and chases—after all, Anderson famously quit film school when an instructor dismissed his enthusiasm for Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991). What is Bob other than a screwball stoner version of Sarah Connor, trying to protect his rebellious, revolutionary-trained teenager from an uncompromising villain? The director also employs another superb Johnny Greenwood score, punctuated by discordant piano notes and sharp strings, which sustains our elevated heart rate with its tempo. Many of his soundtrack choices also feel pointed, from Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers’ “American Girl” for Willa to Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” over the end credits. Most of the songs have a vintage feel, suggesting that the ideas in this film are not new. Pynchon was writing about the same concerns in the 1990s, and as last year’s The Order reminded us, white supremacists have been making plans for decades.

Rather than didacticism or ideological soapboxing (he never mentions Trump, MAGA, or the nebulous antifa), Anderson fuels the story with Bob’s moving race to rescue his daughter. However haphazard, Bob’s clumsy search for Willa prompts plenty of laughs, sure, but it also derives from a touching father-daughter bond that humanizes the material and prevents it from becoming a political diatribe—instead, an overwhelming reunion and catharsis await. Moreover, in today’s climate of Nexstar and Sinclair censoring Jimmy Kimmel for critiquing the current administration, and Apple TV+ delaying a new show that depicts white supremacists as domestic terrorists, it’s admirable to see a film and studio with guts, fearless against an inevitable backlash from the right. Setting aside all of that, One Battle After Another is simply great filmmaking made by a director whose flawless track record remains intact, even as he continues to evolve and experiment. That’s part of what makes Anderson such an intriguing filmmaker: he’s not merely making the same film over and over (see another Anderson named Wes); he grows and reveals new facets to his skill. Much like his title, it’s one film after another, each one as vital as the last.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review