The Definitives

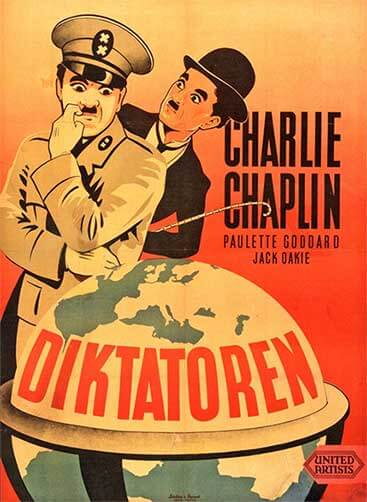

The Great Dictator

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Only Chaplin could have made The Great Dictator in 1940, during a period in Hollywood when a motion picture against Nazism was considered a commercial and political risk. In the years after Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party gained control of Germany, and before the United States was dragged into the Second World War, Hollywood films that depict Hitler, or Hitler-like persons, were limited. The Production Code Administration (PCA) and its chief enforcer, Joseph Breen, censored any negative portrayals of other countries or their leaders to preserve the isolationist and noninterventionist status of the United States. Many politicians, influencers in Hollywood, and American citizens felt that dictators and fascism overseas could not be ignored. They sought to circumvent official policy by alternative means and communicate their protest against the inhuman actions of foreign leaders, while also supporting foreign allies, many under occupation or invasion. For Charles Chaplin, making The Great Dictator in 1940 was a stand for humanism. Chaplin’s satire of Hitler can be logged among a rare few other films from the pre-Pearl Harbor era that defied the cautious times by representing Hitler in no uncertain terms. To make the film, Chaplin earned uncommon approvals and authorizations from the powers that be to take a firm, unwavering stance against Nazism and, perhaps more specifically, Hitler. And while many have critiqued The Great Dictator over the years for its outright political statements that cap an otherwise delightful and sometimes harrowing picture, today, Chaplin’s unflinching work stands as an example of humanism rising to the forefront of cinema out of an impassioned need to combat the racist, megalomaniacal, and dangerous ambitions of world leaders who use their power to dehumanize.

Prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States government and many Americans held an isolationist stance and willfully ignored the looming dangers of Nazi Germany. Although the eventual victory in what would become known as the Good War would be a lasting point of pride for the American people, before Pearl Harbor, the U.S. was still reeling from the loss of life and infrastructural effects of the First World War, and many in the U.S. believed Hitler was Europe’s problem. Along with the Spanish Civil War, the Japanese takeover of China, and Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime in Italy, the march Adolf Hitler’s Stormtroopers across Europe was just another “foreign war” according to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration. This official policy meant that Hollywood was restricted from commenting openly about the European conflict and, at the same time, could not directly acknowledge Hitler’s anti-Semitic pogroms or the plight of Jewish people in Europe under the foot of Nazi oppressors—in part because of many in the U.S. were not yet aware of the full extent of the Holocaust. Though Hitler established himself as the figurehead of the Nazi Party on visual terms by commissioning painted portraits, erecting statues, and disseminating printed propaganda with his image, any depiction of Hitler on film would surely alert Breen’s antennae in the PCA office and represent a potential violation of the Code’s promise to fairly represent “prominent people and citizenry of all nations.” Nevertheless, Chaplin’s The Great Dictator somehow defied the Roosevelt administration, the PCA, the views of many isolationist Americans, and above all, Hitler himself, with a bold caricature of the Nazi leader and an open critique of his anti-Semitism.

To better appreciate why The Great Dictator became such a deeply personal, exceptional lampooning of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, one must have a sense of its author. Charles Chaplin, the most well-known face in Hollywood, and perhaps the world, emerged in the silent era as a superstar of two-reel comedies. In the few short years between his first appearance on the screen in 1914 and 1919, Chaplin worked for a variety of studios—New York Motion Picture Company, Keystone Studios, Essanay, Mutual, First National—and signed contracts with enormous bonuses in the hundreds of thousands. During this time, he became a household name, and his Little Tramp was the screen’s most iconic and beloved figure. Being a scrappy and playful vagrant with a bowler hat, bending cane, and a toothbrush mustache, the character resonated with audiences by holding the appearance of a relatable, crestfallen member of the nobility. The Little Tramp personified the Depression, and millions of moviegoers rushed to their local cinema to see the latest Chaplin short. In 1919, Chaplin’s success and constant artistic conflict with his studios led him to establish the independent distribution company United Artists alongside Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D. W. Griffith, ensuring his artistic control over his output. Having achieved financial and artistic independence at United Artists, Chaplin worked slowly and methodically over the next two decades, releasing a feature-length film every two to five years, as opposed to upwards of ten two-reel comedies per year in his earlier career. Not only would his films become more artistically ambitious, but with artistic autonomy, Chaplin began to place his political and humanist motivations at the forefront of his work.

To better appreciate why The Great Dictator became such a deeply personal, exceptional lampooning of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, one must have a sense of its author. Charles Chaplin, the most well-known face in Hollywood, and perhaps the world, emerged in the silent era as a superstar of two-reel comedies. In the few short years between his first appearance on the screen in 1914 and 1919, Chaplin worked for a variety of studios—New York Motion Picture Company, Keystone Studios, Essanay, Mutual, First National—and signed contracts with enormous bonuses in the hundreds of thousands. During this time, he became a household name, and his Little Tramp was the screen’s most iconic and beloved figure. Being a scrappy and playful vagrant with a bowler hat, bending cane, and a toothbrush mustache, the character resonated with audiences by holding the appearance of a relatable, crestfallen member of the nobility. The Little Tramp personified the Depression, and millions of moviegoers rushed to their local cinema to see the latest Chaplin short. In 1919, Chaplin’s success and constant artistic conflict with his studios led him to establish the independent distribution company United Artists alongside Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D. W. Griffith, ensuring his artistic control over his output. Having achieved financial and artistic independence at United Artists, Chaplin worked slowly and methodically over the next two decades, releasing a feature-length film every two to five years, as opposed to upwards of ten two-reel comedies per year in his earlier career. Not only would his films become more artistically ambitious, but with artistic autonomy, Chaplin began to place his political and humanist motivations at the forefront of his work.

Chaplin’s noted sympathies for an underdog informed both the Little Tramp and his political beliefs. In Modern Times (1938), he satirized the dehumanization of the middle-class worker by the world’s prevailing industrialization, while a growing number of detractors accused him of Communist leanings, to the extent that he eventually left the United States and went into exile in 1952. Chaplin’s humanist compassion led to his emerging anti-fascist views throughout the 1930s. He attended meetings of the Anti-Fascist League and Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, and he soon resolved to aim his creative arsenal at Adolf Hitler. In 1938, Chaplin announced plans to make The Great Dictator, his first full talkie after his slight implementation of sound in Modern Times. Almost immediately after Chaplin announced the picture, German consul Georg Gyssling, the mouthpiece of Joseph Goebbels in Hollywood, protested with Breen at the PCA, while the censor board in England, which had yet to declare war on Germany, promised that Chaplin’s film would go unreleased to avoid their country antagonizing Hitler—a promise that remained until war was declared. Despite these initial protests, Chaplin’s autonomy meant he had no studio executives to appease, meaning he spent his own money to hire actors, pay for the production, and shoot on his own lot, regardless of whether the film’s release was assured.

Serving in his usual capacity as writer, director, producer, star, and composer, Chaplin started shooting his enormous 300-page script just a few days after his home country of England declared war on Germany. The production, Chaplin’s first fully integrated talkie, lasted for 559 days, which was protracted next to the average Hollywood production, but also representative of indulgent masters who insist on perfecting every detail. Later, similarly meticulous filmmakers, including Stanley Kubrick, Terrence Malick, and James Cameron, would demand to oversee every detail, drawing out their production times. Such productions often run long because the studio or backers have granted the filmmaker unusual creative freedoms. Thus, the success of Chaplin’s attack on Hitler relied in part on his considerable means and status—and his political connections. Surprisingly, Breen’s office had just one problem with the entire picture, Chaplin’s use of the prohibited word “lousy,” which the director removed without argument. Then again, Breen’s shocking leniency may have resulted from President Roosevelt’s promise to Chaplin that the film would be released. Or perhaps Breen approved Chaplin’s film because the artist never mentions Hitler by name. Regardless, Chaplin did not disguise his satire out of necessity; he did so because his most powerful weapon against Hitler was laughter. Chaplin resolves to transform Hitler from a domineering, scary figure into an absurd, laughable, and insecure but unquestionably human figure.

Of course, Chaplin intended to play on the similarities between the Little Tramp and Hitler, which commentators had observed throughout the 1930s. The best-loved and most-hated men in the world were born in the same week of 1889; both grew up on the streets, knew poverty well, and eventually rose to sway millions of people through their performances. And then there was their shared toothbrush mustache, which some believed Hitler adopted as a subliminal attempt to redirect the public’s love for Chaplin his way. But there were obviously significant differences. The Little Tramp wore oversized clothes, had a disheveled mop of hair, and bore his signature toothbrush mustache because Chaplin thought it looked funny; Hitler’s dress relied on tight lines and slicked hair, and he wore the same mustache because he thought it was efficient. Yet, both men savored absolute control. After Chaplin achieved independence from the studios, he dominated his sets with fastidious attention to detail. He sometimes required dozens of takes and would often halt productions for days at a time to rethink his approach to a scene, whereas the average Hollywood production could not afford such luxuries of time and perfectionism. As an article in Spectator in April 1939 observed in a critique of Hitler by comparing him to the Little Tramp: “Each is a distorting mirror, the one for good, the other for untold evil.” Hitler despised Chaplin’s success, as the world-famous filmmaker helped raise money through war bonds during First World War. Hitler and Mussolini banned Chaplin’s films given their certitude of his Jewishness, and the Nazis made propaganda films and books calling out Chaplin for being Jewish. On the question of his Jewish heritage, Chaplin maintained, “I do not have that honor.” Hitler’s condemnation of Chaplin spread to the United States, where American isolationist and fascist organizations sent the performer hateful letters after reading about the highly publicized production of The Great Dictator in trade magazines.

Of course, Chaplin intended to play on the similarities between the Little Tramp and Hitler, which commentators had observed throughout the 1930s. The best-loved and most-hated men in the world were born in the same week of 1889; both grew up on the streets, knew poverty well, and eventually rose to sway millions of people through their performances. And then there was their shared toothbrush mustache, which some believed Hitler adopted as a subliminal attempt to redirect the public’s love for Chaplin his way. But there were obviously significant differences. The Little Tramp wore oversized clothes, had a disheveled mop of hair, and bore his signature toothbrush mustache because Chaplin thought it looked funny; Hitler’s dress relied on tight lines and slicked hair, and he wore the same mustache because he thought it was efficient. Yet, both men savored absolute control. After Chaplin achieved independence from the studios, he dominated his sets with fastidious attention to detail. He sometimes required dozens of takes and would often halt productions for days at a time to rethink his approach to a scene, whereas the average Hollywood production could not afford such luxuries of time and perfectionism. As an article in Spectator in April 1939 observed in a critique of Hitler by comparing him to the Little Tramp: “Each is a distorting mirror, the one for good, the other for untold evil.” Hitler despised Chaplin’s success, as the world-famous filmmaker helped raise money through war bonds during First World War. Hitler and Mussolini banned Chaplin’s films given their certitude of his Jewishness, and the Nazis made propaganda films and books calling out Chaplin for being Jewish. On the question of his Jewish heritage, Chaplin maintained, “I do not have that honor.” Hitler’s condemnation of Chaplin spread to the United States, where American isolationist and fascist organizations sent the performer hateful letters after reading about the highly publicized production of The Great Dictator in trade magazines.

On the surface, The Great Dictator is strictly an allegorical representation of Nazism and Hitler, although Chaplin’s lampooning of his subject is unambiguous, and he knew it. Chaplin jokes about the obvious connections between life and fiction, and between himself and Hitler, with his film’s opening title card: “Any resemblance between Hynkel the dictator and the Jewish barber is purely co-incidental.” The film proceeds with two intersecting stories. Chaplin plays Adenoid Hynkel, the Phooey (Führer) of Greater Tomania (to mania), who secured power after the First World War as the Depression and riots rocked his country. Hynkel’s anti-Semitic fascist party seeks to invade their neighboring country, Osterlich, but he must negotiate with another egomaniacal dictator, Benzini Napoloni (Jack Oakie), leader of Bacteria, who also has eyes on Osterlich. Meanwhile, in the Jewish ghetto, the Barber (Chaplin again), a tidier version of the Little Tramp by another name, returns home after years of amnesia following his service in the First World War, unaware of the rampant anti-Semitism in his country. Befriending the resident Hannah (Paulette Goddard, Chaplin’s wife at the time), the Barber faces persecution from Hynkel’s stormtroopers in the ghetto. He is detained and placed in a concentration camp, but he soon escapes in an official uniform. At the same time, stormtroopers find Hynkel duck hunting in civilian clothes, mistake him for the Barber, and detain him. Meanwhile, during his escape, the Barber is mistaken for Hynkel by the party, and he’s rushed to a give a speech at their celebration of the Osterlich invasion. In the final scene, the Barber, speaking as Hynkel, decries fascist thinking and promotes a humanist message.

But the plot remains almost compulsory next to The Great Dictator’s take on Hitler and Nazism, which, upon the film’s U.S. release in October 1940, was completely exceptional and unprecedented in Hollywood. It remains so today. Film historian Richard Schickel wrote that The Great Dictator “as a moral act is probably unsurpassed in American film history.” Self-financed, independent, and free of studio pressure, Chaplin turned Hitler and the Nazi Party into a laughing stock. He transforms the horrific reality of the Nazis into a joke, repurposing their most distinct characteristics into subversive punch lines. Chaplin replaces the swastika with the emblem for Hynkel’s party, two vertical X symbols, referred to as the “double-cross.” Hynkel’s Aryan stormtroopers, almost exclusively an overweight bunch of lugs, march through the Jewish ghetto like drunkards, singing a daffy tune: “We’re the Ar-ryans, the Ary-Ary-Ary-Ary-Ar-ryans!” Chaplin does not find an amusing alternative to the Nazi salute; however, he suggests that Hynkel ordered the Venus de Milo and Rodin’s The Thinker re-sculpted to feature the iconic Nazi greeting. Elsewhere, Chaplin pokes fun at Hitler’s inner circle. Hynkel is accompanied by Billy Gilbert as Field Marshall Herring and Henry Daniels as Minister of Propaganda Garbitsch (pronounced “Garbage”), thin disguises for Hermann Wilhelm Göring and Joseph Goebbels.

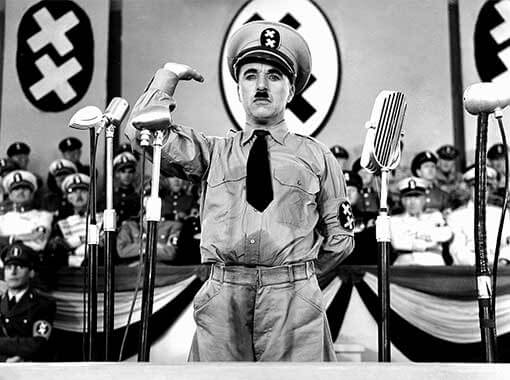

Chaplin’s portrait of Hitler by way of Hynkel is The Great Dictator’s most triumphant satiric stroke, as it reduces Hitler to an absurdist monster and a petty human being. When Hynkel addresses the masses of Tomania, Chaplin performs with Hitler’s rigid, intentional gestures, which the actor had studied (he even once called Hitler a great actor). Hynkel’s speech is German-sounding gibberish in harsh tones, and Chaplin occasionally inserts English words like “sauerkraut” or “cheese and crackers” into the otherwise indecipherable mix, until finally descending into burps and guttural noises, followed by a steady cough. Between applauses, Hynkel waves his hand for a curt, immediate silence from the crowd, and his unintelligible rhetoric is so aggressively performed that microphones bend back on the podium. Much of Chaplin’s caricature involves emasculating or otherwise removing Hitler’s power through humiliation. When Hynkel declares his ambition to become Emperor of the World by building war machines, he must borrow funds from Jewish bankers to fund his operation; as he waits for loan approval, he rescinds his previous anti-Semitic orders to ensure the loan goes through, suggesting his hypocrisy. With world domination in his grasp, he takes a moment to dance with a balloon modeled after a globe in Hitler’s actual offices. This most famous sequence shows Hynkel’s desperation to possess and manhandle the world. He regards the globe wide-eyed and fanatical before spinning it on his finger, and then he bounces it off his foot and head. Chaplin extends the joke when Hynkel lies face-down on his desk to send the globe flying into the air with his bottom. Finally, the balloon pops in Hynkel’s hands and, like a child who has broken his toy, the great dictator sobs.

Chaplin’s portrait of Hitler by way of Hynkel is The Great Dictator’s most triumphant satiric stroke, as it reduces Hitler to an absurdist monster and a petty human being. When Hynkel addresses the masses of Tomania, Chaplin performs with Hitler’s rigid, intentional gestures, which the actor had studied (he even once called Hitler a great actor). Hynkel’s speech is German-sounding gibberish in harsh tones, and Chaplin occasionally inserts English words like “sauerkraut” or “cheese and crackers” into the otherwise indecipherable mix, until finally descending into burps and guttural noises, followed by a steady cough. Between applauses, Hynkel waves his hand for a curt, immediate silence from the crowd, and his unintelligible rhetoric is so aggressively performed that microphones bend back on the podium. Much of Chaplin’s caricature involves emasculating or otherwise removing Hitler’s power through humiliation. When Hynkel declares his ambition to become Emperor of the World by building war machines, he must borrow funds from Jewish bankers to fund his operation; as he waits for loan approval, he rescinds his previous anti-Semitic orders to ensure the loan goes through, suggesting his hypocrisy. With world domination in his grasp, he takes a moment to dance with a balloon modeled after a globe in Hitler’s actual offices. This most famous sequence shows Hynkel’s desperation to possess and manhandle the world. He regards the globe wide-eyed and fanatical before spinning it on his finger, and then he bounces it off his foot and head. Chaplin extends the joke when Hynkel lies face-down on his desk to send the globe flying into the air with his bottom. Finally, the balloon pops in Hynkel’s hands and, like a child who has broken his toy, the great dictator sobs.

Chaplin also addresses Hitler’s narcissism and aggrandization of his own image. Next to Hynkel’s office sits a room where a painter and sculptor wait, and the Phooey enters for mere seconds at a time—between his unrequited, snorting advances at a female secretary—during which the artists frantically try to progress on their portraits. Chaplin’s most effective display of Hynkel’s egoism involves Hitler’s uses of body language to influence his audience by addressing the way he positioned himself from a high angle to the viewer or used strategies to make himself look bigger, more powerful. For this, Chaplin shows Hynkel growing frustrated with his inferiority to Napaloni, whom Oakie portrays with an uncanny resemblance to Mussolini’s bulldog expressions and body language. Despite Garbitsch’s attempts to put Napaloni at a subtle disadvantage, the Bacterian dictator towers over Hynkel and remains unimpressed by the Phooey’s grandiose chancellery, which of course enrages Hynkel. Even Napaloni’s wife leads when she and Hynkel dance. When both men sit down for a shave, Hynkel raises his barber’s chair a bit higher, but then Napaloni boosts his chair for the advantage, and this continues until they have raised themselves fifteen feet in the air. Both shouting, ego-driven, irrational men are ultimately reduced to boyish whining in The Great Dictator by spicy English mustard.

The Great Dictator alternates between comic scenes with Hynkel and those of the Barber in the Jewish ghetto, but Chaplin also alternates between scenes of humor and those of a more serious nature—a tension that later critics admonished. Most of the dramatic scenes involve the persecution of Jews. Hollywood films of the pre-Pearl Harbor era avoided referencing Jewish people at all, disguising them with thin veils, labels such as non-Aryan, or not depicting them at all. The Great Dictator presents a shocking contrast to earlier methods by matter-of-factly representing Hynkel’s anti-Semitic hatred against Jews, as well as the plight of Jewish citizens under the anti-Semitic reign of the Tomanian government. Chaplin depicts Jews in the ghetto who worry about their future, followed by Aryan stormtroopers who paint “JEW” on shop windows and houses, raid Jewish homes, burn shops to the ground, confiscate Jewish property, and gun down Jews in the street. Even so, Chaplin’s references to Jews are not entirely serious. During Hynkel’s initial speech, he talks at length of the “Juden” with a tone of contempt and incredulity in his garbled rhetoric, lowering his voice to a boorish snorting—Hynkel’s personal translator explains, “The Phooey has just referred to the Jewish people.” Chaplin also uses anti-Semitism as a joke, since Hynkel plans to pursue brunette-haired people as his next target (“Brunettes are more trouble than the Jews,” says Hynkel). And Chaplin is quick to point out the hypocrisy of Hynkel’s plan for a blonde-haired, blue-eyed Aryan world “and a Brunette leader.”

Chaplin also portrays the conflict within the Jewish community about whether or not to take action against Hynkel. Since Chaplin had long been a member of Hollywood royalty and maintained close ties with the predominantly Jewish heads of major studios, he surely would have been aware of the pressure on the studios from Jewish community leaders to keep out of the anti-Nazi debate. Chaplin considers both sides, although his use of humor implies the filmmaker’s leanings. He shows the perspective of noninterventionist thinking held by many Jewish community leaders when characters in the ghetto remark, “We Jewish people shouldn’t get mixed up in such business.” Later, one of the Jewish characters says, “Our place is at home looking over our own affairs” in a line that sounds more applicable to an American Jew than someone in Tomania, in the thick of it. Chaplin pokes fun at such attitudes during a scene where several reluctant Jews try to avoid finding a coin that was baked into one of their puddings—a lottery that will determine who among them will sacrifice themselves in an assassination attempt against Hynkel. Chaplin also mocks those reluctant to engage a ruthless dictator and sentimentalizes those willing to speak up or fight back. Note the earnestness of the scene where Hannah says, “That’s what we should all do—fight back. We can’t lick ‘em alone. But we could together.”

Chaplin also portrays the conflict within the Jewish community about whether or not to take action against Hynkel. Since Chaplin had long been a member of Hollywood royalty and maintained close ties with the predominantly Jewish heads of major studios, he surely would have been aware of the pressure on the studios from Jewish community leaders to keep out of the anti-Nazi debate. Chaplin considers both sides, although his use of humor implies the filmmaker’s leanings. He shows the perspective of noninterventionist thinking held by many Jewish community leaders when characters in the ghetto remark, “We Jewish people shouldn’t get mixed up in such business.” Later, one of the Jewish characters says, “Our place is at home looking over our own affairs” in a line that sounds more applicable to an American Jew than someone in Tomania, in the thick of it. Chaplin pokes fun at such attitudes during a scene where several reluctant Jews try to avoid finding a coin that was baked into one of their puddings—a lottery that will determine who among them will sacrifice themselves in an assassination attempt against Hynkel. Chaplin also mocks those reluctant to engage a ruthless dictator and sentimentalizes those willing to speak up or fight back. Note the earnestness of the scene where Hannah says, “That’s what we should all do—fight back. We can’t lick ‘em alone. But we could together.”

Critics and film historians would eventually disapprove of the forthright sincerity throughout in The Great Dictator, such as Hannah’s earnestness or the Jewish barber’s six-minute speech as Hynkel in the last scene. The final speech brings the dramatic momentum to a halt, but its effect is rousing. Chaplin wrote the appeal just after France had fallen to Germany, and its idealism and optimism are only matched by its contagious sentimentality and hope. It’s easy to see why so many have condemned the scene for its intrusion in the overall film, as the speech itself raises the question: Who gives the speech, Chaplin or his character? The Barber hardly seems like a speechmaker. Either Chaplin intended the Barber, with his amnesia, to regard Hynkel’s ideology from an outsider’s what-have-we-become perspective, or it is Chaplin himself who speaks, looking into the camera at the audience. In the former case, the Barber may have been inspired by Garbitsch’s introduction in which he states, “Today, democracy, liberty, and equality are words to fool the people. No nation can progress on such ideas. They stand in the way of action. Therefore we frankly abolish them.” Then again, Chaplin’s aching candor in the ensuing speech implies something more, as though, from within the film, the filmmaker set aside his work to address something more important.

In either case, the scene proceeds as the Barber rises to the stage to give a speech that yearns for the goodness in human beings; weighs how machines, while a potential benefit to the human beings, more often than not separate us; condemns the machine-like existence of the fascist ideology; and praises the power of the people. He opens by stating human beings are generally good people, but that “Greed has poisoned men’s souls, has barricaded the world with hate, has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed.” He calls out how “Our knowledge has made us cynical; our cleverness, hard and unkind” and that “More than machinery, we need humanity.” The soldiers who rely on their industry have turned themselves into machines, into “unnatural men—machine men with machine minds and machine hearts.” The Barber then calls to the people to rise up with an active awareness and willingness to stand against the cruel mechanization of the human heart: “You, the people, have the power, the power to create machines, the power to create happiness! You, the people, have the power to make this life free and beautiful, to make this life a wonderful adventure. Then in the name of democracy, let us use that power. Let us all unite. Let us fight for a new world, a decent world.”

Watching The Great Dictator decades after its release, Schickel altogether dismissed the film for its “horribly botched concluding sequence,” accusing the final speech of having no artistic semblance. But Schickel, age seven upon the film’s release, could not have had the same experience as the film’s contemporary audiences and critics, who viewed the film as a bold anti-Nazi statement that no other Hollywood studio was willing to make. The young Schickel was likely unaware of Hollywood’s lack of outspoken commentary against Nazis and Adolf Hitler, and what is more, he could only view the film from a historical context later in life through the lens of criticism and dramatic structure. Some of the film’s contemporary critics noted how the speech threatens to undo the entire experience, such as The Sunday Times critic who wrote, “This finale is so blatantly out of harmony with what has gone before as to nullify much of the effectiveness of the preceding two hours.” But most viewers and critics at the time viewed Chaplin and his speechifying politics as representative of his David-and-Goliath motif in his film and, further, throughout his career. In Hollywood, Chaplin’s boldness with The Great Dictator and its speech were well received, with many reprinting the speech. Director Archie Mayo included it with his Christmas card in 1940.

Watching The Great Dictator decades after its release, Schickel altogether dismissed the film for its “horribly botched concluding sequence,” accusing the final speech of having no artistic semblance. But Schickel, age seven upon the film’s release, could not have had the same experience as the film’s contemporary audiences and critics, who viewed the film as a bold anti-Nazi statement that no other Hollywood studio was willing to make. The young Schickel was likely unaware of Hollywood’s lack of outspoken commentary against Nazis and Adolf Hitler, and what is more, he could only view the film from a historical context later in life through the lens of criticism and dramatic structure. Some of the film’s contemporary critics noted how the speech threatens to undo the entire experience, such as The Sunday Times critic who wrote, “This finale is so blatantly out of harmony with what has gone before as to nullify much of the effectiveness of the preceding two hours.” But most viewers and critics at the time viewed Chaplin and his speechifying politics as representative of his David-and-Goliath motif in his film and, further, throughout his career. In Hollywood, Chaplin’s boldness with The Great Dictator and its speech were well received, with many reprinting the speech. Director Archie Mayo included it with his Christmas card in 1940.

Years after the Second World War, Chaplin said he would have never made The Great Dictator had he known the full extent of the horrors of the Holocaust. This remark speaks to the degree to which people in the United States, even someone of Chaplin’s considerable influence, remained uncertain and uninformed about the genocide in Europe. Whether more knowledge about the reality of the Holocaust’s atrocity would have swayed the isolationists in the U.S., who can say. But such uninformed views certainly explain why The Great Dictator depicts the Barber’s experience in a concentration camp as no more oppressive or dehumanizing than a federal penitentiary—complete with a numbered jumpsuit and a handwritten letter from Hannah delivered to his cot. Chaplin’s ignorance allows for darker humor, such as a grim line delivered by the gleeful Herring: “We’ve just discovered the most wonderful, the most marvelous poisonous gas. It will kill everybody!” Perhaps, with full knowledge of the Holocaust’s horrors, Chaplin would have omitted the dark comic strains and made something more dramatic, or perhaps he would have focused his time and money on humanitarianism, or combating isolationism in America. Nevertheless, Chaplin’s film remains the pre-Pearl Harbor era’s most potent anti-Nazi film by carefully attacking Hitler and his fascist party, as opposed to all of Nazi Germany, while acknowledging not every German hates Jews and not every German is a Nazi.

By wielding the power of laughter to destabilize Hitler’s authority, Chaplin’s satire acknowledged the enormous absurdity of such blatant egomania and hatred spewing from the Nazi leader, and his film became a rare open protest against Nazism in pre-Pearl Harbor Hollywood. The fascist authority mocked in The Great Dictator is one of comically outlandish selfdom, ironically perpetuated by another domineering individual. But while Chaplin’s desire for control guided his art, that art contained boundless humanism that reached beyond borders, religion, race, or politics. For Chaplin, Hitler and those like him were obvious living caricatures, using their bold, yet false personas to convince the populace of their ersatz superiority and cruel agendas. Chaplin’s film demands the audience recognize the oversized, dangerous ego of a ruler determined to suppress, deny, discount, and create divisions between people. As the Barber announces in his speech, “We all want to help one another. Human beings are like that. We want to live by each other’s happiness—not by each other’s misery. We don’t want to hate and despise one another. In this world there is room for everyone, and the good earth is rich and can provide for everyone, the way of life can be free and beautiful. But we have lost the way.” Chaplin’s attack on Nazism provides a brave cautionary tale, not only against Hitlerism, but against future leaders who would govern by propelling hatred rather than spreading good will among human beings. Chaplin beckons the viewer to recognize and fight against tyrants, and every few years, as another despot comes along, The Great Dictator becomes achingly relevant again.

Bibliography:

Brownlow, Kevin, and Michael Kloft, directors. “The Tramp and the Dictator,” 2001. The Great Dictator. The Criterion Collection. Blu-ray.

Koppes, Clayton R. and Gregory D. Black. Hollywood Goes to War: How Politics, Profits and Propaganda Shaped World War II Movies. University of California Press, 1987.

McLaughlin, Robert L. and Sally E. Parry. We’ll Always Have the Movies: American Cinema During World War II. The University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Robinson, David. Chaplin: His Life and Art. McGraw-Hill, second edition, 2001.

Sarris, Andrew. “The Most Harmonious Comedian.” The Essential Chaplin: Perspectives on the Life and Art of the Great Comedian. Edited by Richard Schickel. I.R. Dee, 2006, pp. 45-58.

Schickel, Richard. “Introduction: The Tramp Transformed.” The Essential Chaplin: Perspectives on the Life and Art of the Great Comedian. I.R. Dee, 2006, pp. 1-41.

Vance, Jeffrey. Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema. Harry N. Abrams, 2003.

(Note: The above was excerpted and re-edited from a Master’s thesis, An Undeclared War: Hollywood’s Pre-Pearl Harbor Anti-Nazi Cinema.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review