Reader's Choice

Billy Madison

By Brian Eggert |

Billy Madison is a film about the redemption of the soul. The 1995 comedy, starring Saturday Night Live alumnus Adam Sandler in his first big-screen showcase, grossed enough at the U.S. box office to ensure his place in comedies for the next 25 years, for better or worse. Sandler brings his popular gibberish-voiced, song-singing persona from television into the movie, and though Billy Madison is often cited for its juvenile humor and penchant for randomness, upon closer inspection it can be interpreted as having powerful themes about atonement, growing up, and recovering from a life of sin. Perhaps such ideas were not intended by writers Sandler and Tim Herlihy; however, director Tamra Davis’ clear use of symbolism throughout makes the movie’s more substantive motives difficult to deny. What makes the movie, which runs a mere 89 minutes, seem so trivial is the humorous context from which its larger themes unfold. Nevertheless, Billy Madison is a morality tale that pushes its titular character from a profound state of depravity and guilt into a quest to save his own soul.

The driving symbolism of the movie is embedded into the story so intricately that the viewer may not even notice, as they would be focused too much on the laughter, occasional songs, and silly situations. Taken from one perspective, the movie is just a goofy story of Sandler’s twentysomething layabout, Billy Madison, a serial partier whose father (Darrin McGavin), the owner of a prestigious line of hotels, paid off Billy’s teachers from the first grade onward. Due to Billy’s chronic drunkenness, idiocy, and irresponsible behavior, his father has resolved to give the company to Eric (Bradley Whitford), a duplicitous second-in-line executive. This news snaps Billy out of his complacency. To save the company from falling into Eric’s clutches, he resolves to go back to school, complete each grade in two weeks, and earn his father’s respect. Inevitably, that’s just what happens, culminating with an “academic decathlon” against Eric. Along the way, Billy makes several new friends and starts a romance with his (second) third-grade teacher Veronica Vaughn (Bridgette Wilson), while Eric reveals himself to be incapable of running a Fortune 500 company.

From another perspective, Billy Madison is a movie rich with imagery that reflects its protagonist’s desperate need to save his soul and redeem himself. Billy’s life is one of overindulgence and immorality, established in the first scenes that show his ritualized binge drinking and penchant for nudie magazines like “Drunk Chicks”. His debauched behavior, regretfully indulged by his father, has carried over from his youthful heyday in the 1980s, the decade of greed and excess. Ever since, Billy has remained in a state of sin and, by extension, arrested development—evidenced by his persistent use of baby talk in the movie’s first half. Indeed, the movie draws correlations between Billy’s crude behavior and his inability to grow up as signs that his soul remains in jeopardy. But as he commits himself to his own education and betterment, he gradually moves away from a life of sin and alcohol; he no longer wants to binge drink, light bags of poo on fire, or force donkeys to drink beer—and he becomes a fully formed individual who uses a grown-up voice. And throughout the movie, the viewer finds other critical symbols that chart Billy’s redemption arc.

The movie’s morality tale symbolism begins almost immediately with the presence of a hallucinated, human-sized penguin. It appears to Billy in the first scenes, where he has hit rock bottom. He begins chasing the penguin, which draws him closer to the Madison mansion entrance where his father’s colleagues have gathered for an announcement, and where Billy proceeds to pass out, embarrassing himself and his father. It is this behavior that convinces Billy’s father that his son is incapable of handling the company when he retires, thus propelling the movie’s adult-buffoon-goes-back-to-school scenario into motion. The penguin reappears throughout the movie when Billy is at his lowest points. Note Billy’s observation in the opening sequence that it’s “too damn hot for a penguin to just be walkin’ around.” This remark is a reminder that Billy leads a life of sin, and in his current state, he can feel the fires of Hell. The penguin, a cold climate animal, appears when Billy is at his worst and seems to beckon him to cool down and avoid the scorching hellfire that awaits him should he continue to live this way. The penguin appears again after Eric seems to get the upper hand and, feeling hopeless, Billy backslides. In a drunken stupor, Billy appears on Veronica’s doorstep, and when she opens the door, he sees the penguin inside, holding a cocktail. He assumes the worst, that Veronica and the penguin have been having a romantic tryst. But later, after Veronica convinces Billy to sober up and stop Eric, he no longer sees the penguin as the threat of Hell has subsided.

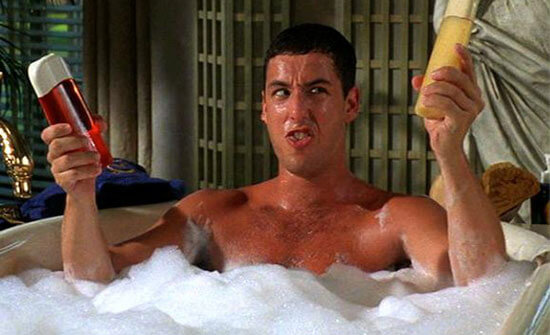

But the penguin is one of many symbols in Billy Madison that evokes the character’s inner conflict between sin and righteousness. Consider the famous scene of Billy in the bathtub as another example of Billy wrestling with himself to save his own soul. He asks himself which is better, shampoo or conditioner? But these are more than just hair care products. The question is really whether he wants to clean his soul and reform or continue with the silky life of sin in which he has lost himself. Does he prefer to cleanse his soul with shampoo, which will wash away his sins? Or does he prefer conditioner, which gives him the ability to luxuriate in the velvety softness that his life of leisure affords him? In the bath, he crashes the two bottles together, unable to decide, until they are lost in the bathwater. At this, he turns to the tub faucet, which has the shape of a swan, a symbol of purity that, at this moment, confronts Billy with the reality of his own sinfulness. “Stop looking at me, swan,” he says, in a statement that reveals Billy’s refusal at that moment to address what may become of his soul if he continues on his current path.

Although Billy overcomes his excessive drinking and irresponsible behavior with relative ease once he goes back to school, his bullying behavior represents another condition that he must overcome. Billy Madison contains several subplots that involve bullies and bullying behavior as further symbols of the protagonist wrestling with his soul. When Billy first goes back to elementary school, he berates his classmates, shouting in their faces or pummeling them in a game of dodgeball. When he enters Veronica’s third-grade class, he mocks a fellow student who stutters when reading aloud. At this, Veronica takes Billy by the ear and pulls him into the hallway. “Making fun of a little kid trying to read […] Do you not have a soul?” This question permeates the movie as Billy grapples with his own bullying behavior; he gradually proves that he does have a soul when he discourages and atones for his own bullying in several instances. During a field trip, his friend Ernie pees his pants, Billy proceeds to splash water on his groin so it appears as though he too has peed his pants. He makes sure the other students notice: “Of course I peed my pants. Everybody my age pees their pants—it’s the coolest!” Now that peeing your pants is seen as cool, Ernie has no need to be embarrassed about his accident or worry that he might be bullied because of it.

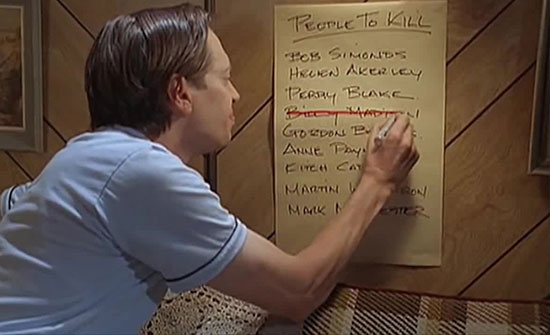

Bullying is a central component of Billy’s former wicked lifestyle and his redemption arc. Although Billy Madison associates bullying with sinful behavior, it also suggests that bullies are doomed figures and therefore underscores the gravity of the conflict. Not only does Billy’s soul hang in the balance because of bullying, but his life seems to hang in the balance as well. After Veronica confronts Billy about his bullying, he begins to examine his past behavior. One night, he calls a former high school classmate named Danny McGrath (Steve Buscemi) and apologizes for his “mean and stupid” actions in the past, and Danny accepts his apology. It’s a decision that proves fateful, as Danny crosses out Billy’s name from his “people to kill” list. In a different twist of fate, watch what happens to the O’Doyles—an entire family of bullies who build themselves up (“O’Doyle rules!”) by putting others down. By chance, a discarded banana peel causes the O’Doyle family car to swerve off a cliff, and the O’Doyles succumb to the same outcome as all unreformed bullies in Billy Madison: death.

If the movie can be read as a tale of Billy saving his soul by redeeming his sins, then Eric is a Satan figure who attempts to corrupt Billy. Described as a “bad, bad man,” Eric wants Billy to continue his lifestyle of drinking and debauchery because it means he can take over the company, but perhaps it also means he will collect Billy’s soul. When Billy is first confronted with the idea of Eric taking over his father’s company, Eric attempts to convince Billy by tempting him with sin: “You don’t ever have to look for a job. You can sit around all day, goofing off, sipping drinks.” Once Billy refuses, and he goes back to school to prove to his father that he’s not a fool, Eric goes to more menacing lengths. He exploits the sins of others to his benefit, such as when he blackmails Principal Max Anderson (Josh Mostel), using his sordid past in wrestling to convince him to lie about Billy. Elsewhere, Eric pushes children, refuses to enjoy Billy’s grade-level graduation parties, and puts his secretary into a coma. He even resembles a fiendish figure, complete with an insidious grin, a weasel laugh, and a grim office where he torments a caged rodent. His devilish appearance begs the question: When Eric is pushed over a bench during the academic decathlon, and two teen boys glimpse his balls, what did they see? Were they human balls, or were they the balls of Satan?

Though Billy manages to redeem himself by the end of the movie, he does so in a roundabout way, otherwise unconnected to education, which threatens to derail some of Billy Madison’s otherwise consistent themes. Note how Billy’s performance in the academic decathlon involves cheating in the chemistry round, where he pulls his own shoe from a bubbling container, much to the excitement of the teacher (Robert Smigel). In most rounds, actually, Billy’s performance is subpar. His rambling answer in a round of academic speeches incites a vicious response from the judge: “I award you no points, and may God have mercy on your soul.” But education is not equivalent to a clean soul in the movie. Billy Madison is more about living a life without sin, and school is the platform where Billy learns this lesson. Without it, he never would have stopped drinking, nor would he have realized the folly of bullying, and these lessons ultimately save him. When Eric sees he is defeated, he pulls a gun, laughing maniacally as he aims at Billy’s beloved Veronica. At that instant, Danny McGrath appears and shoots Eric down, a turn of events that would have gone very differently if Billy had not sought the redemption of his soul and apologized to Danny. Indeed, those committed to a life of sin in Billy Madison, from Eric to the O’Doyles, meet a disastrous end.

Though Billy manages to redeem himself by the end of the movie, he does so in a roundabout way, otherwise unconnected to education, which threatens to derail some of Billy Madison’s otherwise consistent themes. Note how Billy’s performance in the academic decathlon involves cheating in the chemistry round, where he pulls his own shoe from a bubbling container, much to the excitement of the teacher (Robert Smigel). In most rounds, actually, Billy’s performance is subpar. His rambling answer in a round of academic speeches incites a vicious response from the judge: “I award you no points, and may God have mercy on your soul.” But education is not equivalent to a clean soul in the movie. Billy Madison is more about living a life without sin, and school is the platform where Billy learns this lesson. Without it, he never would have stopped drinking, nor would he have realized the folly of bullying, and these lessons ultimately save him. When Eric sees he is defeated, he pulls a gun, laughing maniacally as he aims at Billy’s beloved Veronica. At that instant, Danny McGrath appears and shoots Eric down, a turn of events that would have gone very differently if Billy had not sought the redemption of his soul and apologized to Danny. Indeed, those committed to a life of sin in Billy Madison, from Eric to the O’Doyles, meet a disastrous end.

Viewed as an absurdist comedy by many, Billy Madison is nonetheless the product of a director who specializes in cautionary tales about the temptations of sin putting one’s soul in jeopardy. Tamra Davis also made CB4 (1993), starring Chris Rock as a young man who takes on the false identity of a gangster rapper to acquire fame and fortune, but he realizes he has lost himself in the process; Half Baked (1998), about stoners who learn the consequence of excessive drug use and distribution; and Crossroads (2002), the Britney Spears vehicle about a series of youthful transgressions that lead to a message of female empowerment. In Billy Madison, Davis makes use of Adam Sandler’s foolish comic stylings for a greater lesson about cleansing the soul and finding salvation through good behavior and sobriety. She achieves this with a rich use of symbolism that’s evident in many of the primary scenes and characters, and even some imagined ones. If there is a significant fault to be found in the movie, it’s the frequent bouts of randomness that divert from its moral thrust, which have led to many viewers overlooking its finer lessons about the condition of the soul.

(Editor’s Note: Thanks to Aaron, who suggested and commissioned this review on Patreon!)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review