Mistress America

By Brian Eggert |

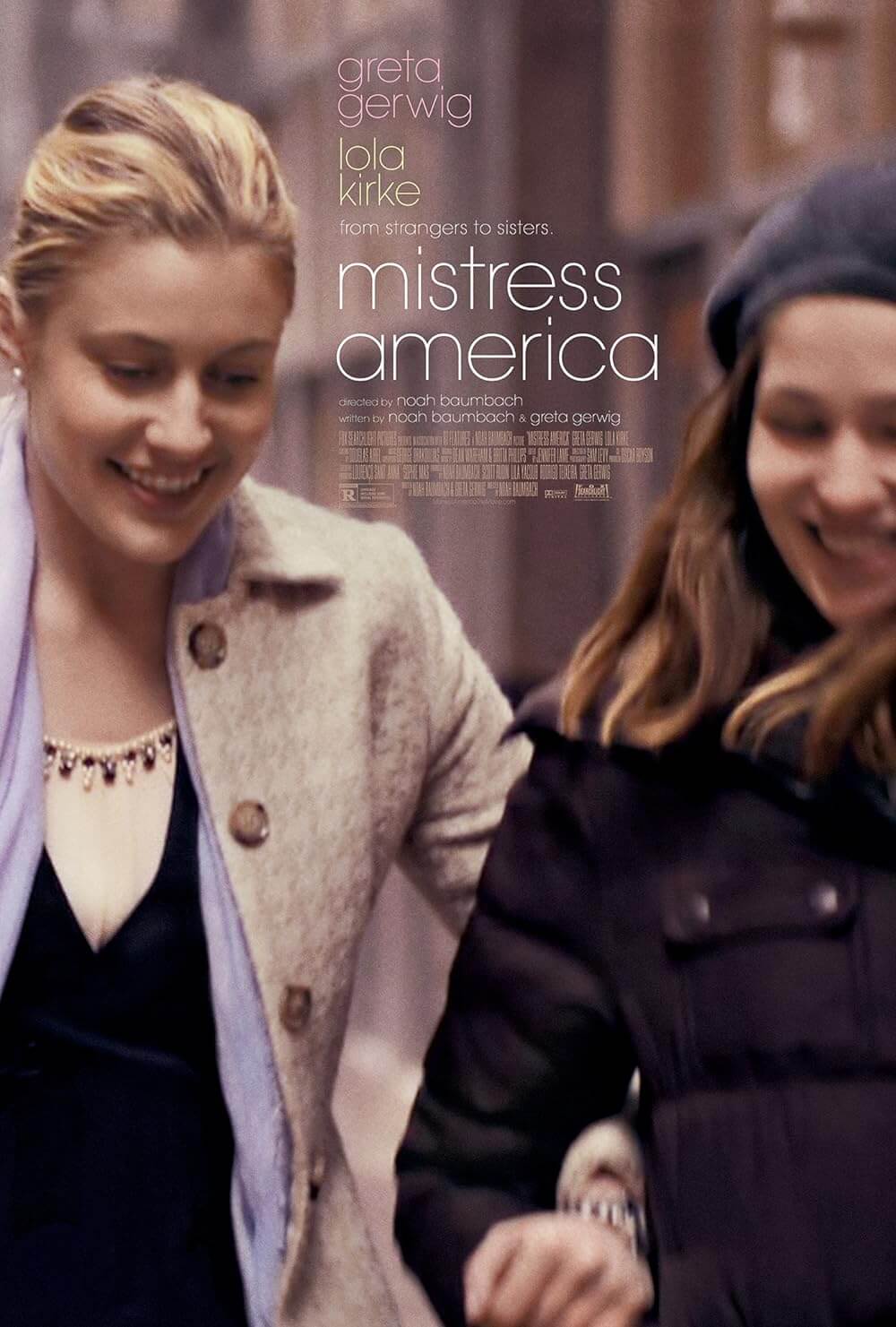

A little more than midway through Mistress America, Noah Baumbach directs his most comically brilliant sequence in a showcase of screwball fancy. With equal measures of inspiration from Preston Sturges and Woody Allen, Baumbach orchestrates a slowly building farcical situation in a Connecticut estate (the final setting of Sturges’ screwball great The Lady Eve). Somehow both ditzy and commanding, Brooke, played with whimsy by Greta Gerwig, pitches her restaurant idea to an old boyfriend (Michael Chernus) and his wife, Brooke’s ex-friend (Heather Lind), who stole her million-dollar t-shirt idea. We’re thrust headlong into a progression of comic entrances and exists, situational turnovers, and no end of complications. There’s a nosy neighbor, a pregnant woman, a jealous lover (or two), and a well-to-do benefactor. And yet, the dazzling and wonderfully timed comedy gives way to an emotional fallout. Like the rest of Mistress America‘s brisk 84 minutes, this sequence is handled with pitch-perfect control by Baumbach.

Although it originally debuted at Sundance in early 2014, Mistress America is Baumbach’s second film released in 2015, after March’s While We’re Young. The wait has been long for Baumbach fans (since 2012’s Frances Ha, also starring Gerwig), but well worth it. The New York director’s similarly themed titles are each about our fixation on how we’re supposed to act according to our age. In While We’re Young, Ben Stiller and Naomi Watts play insecure fortysomethings who latch-on to a younger couple (Adam Driver, Amanda Seyfried) to revitalize their own marriage, taking on the qualities of youthful hipsters. In Mistress America, Brooke, who’s thirty, has all the jazzed-up energy of someone with all the potential in the world, except that potential is running out. She’s the sister-to-be of Tracy (Lola Kirke), a hopeful writer and freshman at Barnard College. Tracy’s divorcee mother (Kathryn Erbe) will soon marry Brooke’s widower father, and to prepare for their future sisterhood, Tracy calls up her future big-sis. Around the 18-year-old Tracy, Brooke feels old. “We’re ten, twelve years apart,” Brooke defends in one scene. “We’re contemporaries.”

Baumbach’s muse from Greenberg and Frances Ha, Gerwig gives Brooke life with all of the considerable charms—and vulnerabilities—she brings to the screen. Consider her entrance, when Tracy watches as Brooke makes her way down the flashy red steps near the TKTS Discount Booths in Times Square. About twenty steps up, Brooke appears open-armed, like a celebrity descending on a red carpet. Except Baumbach doesn’t break the shot, and as the scene keeps going and it takes longer than Brooke expected to take every deliberate step, the grandiose moment becomes awkward. That’s Brooke—full of energy and promise, but ultimately a washout, yet no less delightful for her failures. She’s a self-styled social-media maven, wannabe interior designer, part-time tutor, and spin-class instructor. She’s invited onstage to dance with the band at a hipster club. People snap photos of her; she no doubt loves the attention, but insists, “Do we have to document ourselves all of the time?” She’s kind of person who says she knows everything about herself, so she’s immune to therapy.

Tracy resides somewhere looking in, on the margins. Whether she does this by design or unintentionally, who can say? Perhaps even she doesn’t know. Lonely, she laments going to school, which she describes like “being at a party where you don’t know anybody, all the time.” Her only friend is a would-be conquest, a fellow aspiring writer and a nervy type played with comic aplomb by newcomer Matthew Shear; only, that idea is quickly shot-down when Tracy sees him holding hands with his bluntly jealous girlfriend (Jasmine Cephas-Jones). To earn a coveted spot on a campus literary magazine, Tracy lingers around Brooke and uses her pointedly New Yorker energy to inspire her writing. At first it seems as though Tracy’s identity will be informed by Brooke, and that once again Baumbach is showing us how one age group clings to another; however, Tracy turns out to be more certain of herself than she seems, and the inspiration flows the other way.

Kirke participated in Baumbach’s film before shooting her role in Gone Girl, as the trashy drifter who befriends and robs Rosamund Pike’s character. The 24-year-old actress blends chameleon-like into her seemingly naive, yet watchful character. She also shares an incredible chemistry with Gerwig, whose high-energy talks about whatever comes to mind wisp away both Tracy and the audience. There’s a hilarious and telling moment when the two go out dancing, where Tracy says something-or-other about frozen yogurt, and in response, Brooke drops, “I watched my mother die.” At first, this seems like another symptom of Brooke’s very impulsive, matter-of-fact, tell-all personality. (Another example: She says of her fiancé, whose off in Greece on a business deal, “He’s the kind of person I hate, except I’m in love with him.”) But later, Brooke proves to be far more vulnerable and frightened of the world around her.

Baumbach and Gerwig wrote Miss America together, playing to Gerwig’s strengths, testing the limits of Baumbach’s direction, and once more tapping into intense female relationships. What seems farcical and fun-loving at times breaks down into a tender story, as this director’s films often do. Though the film is ultimately told from Tracy’s perspective, it’s all about Brooke, and to a greater extent the experiences and people that shape and inspire artists (specifically Baumbach’s penchant for authors). In Brooke’s case, she aspires to be a creative type, but, tragically, she doesn’t have the follow-through to carry out her ideas. As Baumbach’s frequent author-protagonists often realize, the people who endeavor and fail often make the best subjects. They may not recognize it themselves, but they are the artist’s muse, the mistress who reinvigorates the dead marriage between art and the artist. It’s a fascinating metaphor in a film that’s funny and touching, and another welcome picture from Baumbach and Gerwig.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review