Nazi Agent

By Brian Eggert |

Nazi Agent from 1942 stands among Hollywood’s efforts to mobilize and garner support for World War II through motion pictures. Although by 1942 Japan had just bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States economy surged to prepare the military for a response, many Americans still had no idea about what Nazis stood for, except that they were the enemy. Beyond the appearance of Nazis in newsreels, Hollywood, backed by the U.S. government, went to great lengths to define the Nazi ideology for viewers in hundreds of message films, everything from Tarzan Triumphs (1943), where the famous ape-man fights against the Nazi invasion of Africa, to Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror (1942), where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s legendary detective exposes covert Nazi radio broadcasts heard on the BBC. Nazi Agent has a typical kind of message for the period, where the hero stops an invisible invasion of Nazi spies on home turf, and with the threat resolved, the picture reminds audiences to invest in war bonds. Nevertheless, the film remains significant as an early effort from director Jules Dassin, while also boasting terrific dual performances by Conrad Veidt.

During the war years, Hollywood helped popularize the myth of foreign spies on U.S. soil. Propaganda posters that warned “Careless talk costs lives” and “Loose lips sink ships” emphasized the notion that anyone, even a friend or loved one, could be working for the enemy. The studios made excellent use of this rampant paranoia in an entire subgenre of spy-thrillers and espionage melodramas. Due to the lack of accurate information about Nazis, Hollywood screenwriters were left to invent the frightening possibilities of Nazi espionage. On rare occasion, the studios based their yarns on actual incidents, as with Warner Bros.’ Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939), based on a real-life espionage case from 1937 that led to three arrests. In most cases, tales of spies in America, like Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942), were pure fiction. And while it might seem as though Hollywood was fueling undue paranoia throughout the country, the FBI would report in 1945 that thousands of enemy agents, schemers, and dangerous persons were arrested after the start of the war. Indeed, the FBI and even Average Joe American had become adept in Nazi counterintelligence, leaving the U.S. almost entirely spared of successful enemy sabotage or significant acts of espionage. In effect, fear over enemy spies led to a ubiquitous sense of distrust that ironically helped unify the country.

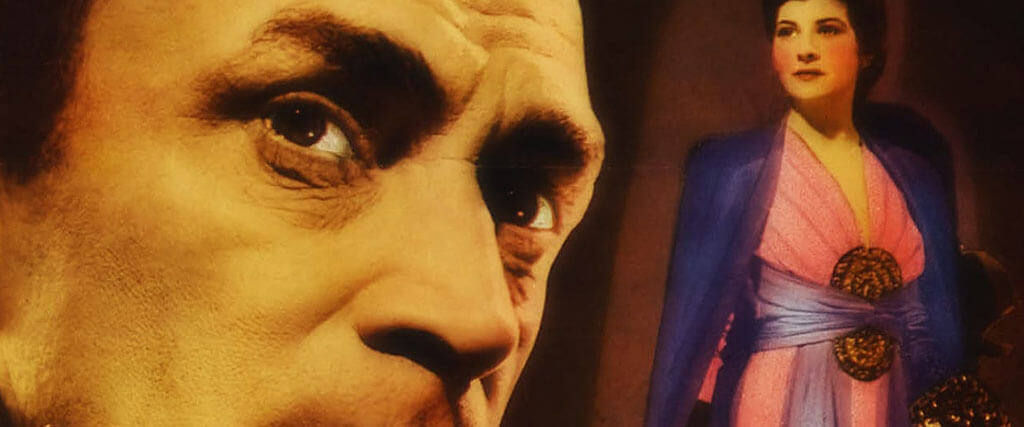

Nazi Agent’s basic plot takes place before Pearl Harbor and involves two identical twins of a prestigious German family, both played by Conrad Veidt. The good twin, a bibliophile and German-expatriate-turned-American-citizen named Otto Becker, left his home country before the Nazis came to power. Becker operates a rare bookstore in New York; at night, he retires to his apartment above the store, accompanied by his sole companion—a canary that will only sing in his presence. The other sibling, Baron Hugo von Detner, serves as a German consul in New York, though he doubles as the leader of a Nazi spy ring, using his official position in the U.S. to obtain secrets for the Nazi Party. One evening, von Detner confronts his brother, coercing the use of Becker’s store as a front for Nazi activity. Becker, who loves America and considers it his home, eventually kills his brother and, to avoid being captured by his brother’s Nazi friends, the bearded hero shaves and wears his brother’s monocle, adopting his brother’s Nazi identity to expose the spy ring from the inside. Meanwhile, Becker sacrifices his own identity.

Nazi Agent’s basic plot takes place before Pearl Harbor and involves two identical twins of a prestigious German family, both played by Conrad Veidt. The good twin, a bibliophile and German-expatriate-turned-American-citizen named Otto Becker, left his home country before the Nazis came to power. Becker operates a rare bookstore in New York; at night, he retires to his apartment above the store, accompanied by his sole companion—a canary that will only sing in his presence. The other sibling, Baron Hugo von Detner, serves as a German consul in New York, though he doubles as the leader of a Nazi spy ring, using his official position in the U.S. to obtain secrets for the Nazi Party. One evening, von Detner confronts his brother, coercing the use of Becker’s store as a front for Nazi activity. Becker, who loves America and considers it his home, eventually kills his brother and, to avoid being captured by his brother’s Nazi friends, the bearded hero shaves and wears his brother’s monocle, adopting his brother’s Nazi identity to expose the spy ring from the inside. Meanwhile, Becker sacrifices his own identity.

Anonymously and under the noses of the Nazis, Becker provides the police with details about several Nazi schemes, but the enemy spies begin to realize something is amiss, leading to some well-earned suspense. The family servant working for von Detner realizes his employer must be Becker in disguise given the appearance of a scar on his shoulder. An icy Nazi named Miss Harper (Dorothy Tree) notices that Becker’s canary now sings whenever von Detner enters the room. A romantic subplot develops between Becker and Kaaren De Reele (Anne Ayars, who later became an opera performer), a sympathetic female informant strong-armed by the Nazis, giving the finale ample emotional weight. Before long, Becker’s disruption of the Nazi schemes is exposed, yet so are the Nazi spies. Everyone in the German consulate will be deported, but the Nazis plan to kill both Becker and Kaaren for sabotaging their sabotage. Becker makes a deal with them. He agrees to return to Germany, where they can deliver him as “a traitor to Nazi justice” in a victory for the Nazis, but only if they allow Kaaren to live. The Nazis agree. The final scene shows Becker on a boat to Germany, looking at the Statue of Liberty from New York harbor with tears filling his eyes, doomed but proud.

Veidt would play spies and Nazis throughout his Hollywood career. Born in Berlin in 1893, he studied acting at a young age, starting on the stage under director Max Reinhardt at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin, and then to German film, where he made landmark appearances in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and The Man Who Laughs (1928). Veidt’s fame and talent led to his being coaxed to England in the early 1930s. Not long after he married his third wife, who was Jewish, the Nazi Party rose to power in Germany. The actor resolved to remain in England. He was so devoted to his wife and that he even registered himself as Jewish in an act of defiance and support. Veidt became a British citizen in 1938 after appearing in many of the local industry’s productions, including two films for Michael Powell, The Spy in Black (1939) and Contraband (1940). Along with many other British talents during the war, Veidt moved to Hollywood in 1940, where he was almost exclusively cast as Nazis, including memorable roles in All Through the Night (1941) and Casablanca (1942). Veidt’s life and career in Hollywood were cut short by his sudden death from a heart attack in 1943.

Veidt’s dual role in Nazi Agent must have been personal for the actor. It allowed him to portray in Becker a character not unlike himself—a German who refuses to go along with the fascist fervor that had overtaken many of his countrymen. Moreover, the screenplay by Paul Gangelin, John Meehan, Jr., and Lothar Mendes may have based von Detner on the German consul of Los Angeles, Georg Gyssling, a dutiful Nazi since 1931 who served in Hollywood from 1933 to 1941. Gyssling communicated regularly with Joseph Breen, the so-called Czar of the Production Code Administration (PCA), and because Gyssling reported directly to Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler’s propaganda minister had shocking influence over Hollywood’s depiction of Germans and the Nazis before Pearl Harbor. Working with the PCA before the United States was pulled into World War II, when the country remained predominantly isolationist and considered Nazis to be the rest of the world’s problem, Gyssling used his influence on Breen to ensure no anti-German or even anti-Nazi sentiments made it into motion pictures in the years preceding the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Veidt’s dual role in Nazi Agent must have been personal for the actor. It allowed him to portray in Becker a character not unlike himself—a German who refuses to go along with the fascist fervor that had overtaken many of his countrymen. Moreover, the screenplay by Paul Gangelin, John Meehan, Jr., and Lothar Mendes may have based von Detner on the German consul of Los Angeles, Georg Gyssling, a dutiful Nazi since 1931 who served in Hollywood from 1933 to 1941. Gyssling communicated regularly with Joseph Breen, the so-called Czar of the Production Code Administration (PCA), and because Gyssling reported directly to Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler’s propaganda minister had shocking influence over Hollywood’s depiction of Germans and the Nazis before Pearl Harbor. Working with the PCA before the United States was pulled into World War II, when the country remained predominantly isolationist and considered Nazis to be the rest of the world’s problem, Gyssling used his influence on Breen to ensure no anti-German or even anti-Nazi sentiments made it into motion pictures in the years preceding the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor.

For instance, in 1936, MGM planned to adapt Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 anti-fascist novel, It Can’t Happen Here, a dystopian cautionary tale about a fascist seizure of the United States government. Louis B. Mayer paid Lewis $50,000 and secured the novel’s rights, and then hired Sidney Howard, who would later adapt Gone with the Wind (1939), to write the screenplay. Mayer paid Howard thousands for his work on the script, and in the meantime, he cast Lionel Barrymore, Basil Rathbone, and a young Jimmy Stewart to appear in the film. But Gyssling protested to Breen about the anti-fascist themes in the proposed film, and because the U.S. did not want to upset Germany and Italy, Breen recommended more than 60 changes to the existing script to make it acceptable for distribution. Breen’s request would make the production impossible if not pointless. Mayer resolved not to proceed with the production, despite having already spent $200,000 developing it. Although Gyssling’s tactics and Nazi loyalties were eventually exposed by Hollywood’s Anti-Nazi League, his protests shaped and ultimately tamed Hollywood’s anti-Nazi messages before Pearl Harbor. Quite daringly so, Nazi Agent seems to call out the common belief that many German consuls in the United States during this time were either confirmed Nazis or sympathizers.

Nazi Agent also marks the feature-length debut of Jules Dassin, who went on to direct some of the most memorable film noirs from the 1940s and 1950s, including Thieves’ Highway (1949) and Night and the City (1950). Like Veidt, Dassin started in the theater as a member of the ARTEF Players in the 1930s, a Jewish socialist theater collective, and then directed his first Broadway production in 1939. Along with many Broadway talents of the era, he was charmed from the East Coast to Hollywood. He signed with RKO in 1940 in advance of moving to MGM, where he made short subjects before graduating to features with Nazi Agent. After workmanlike releases under MGM, Dassin signed with producer Mark Hellinger, a partnership that resulted in Brute Force (1947) and The Naked City (1948)—films imbued with the dehumanizing effect of postwar America. How fitting, since the director would later become a victim to McCarthyism during this period. Edward Dmytryk and Frank Tuttle named Dassin as a member of a Hollywood Communist group in their House Un-American Activities Committee testimony in 1951. Dassin, after being blacklisted from Hollywood, moved to Europe and made films like Rififi, an essential heist film that won him the Best Director Award at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival.

Of course, Nazi Agent doesn’t have the biting commentary, chiaroscuro style, or cynicism of Dassin’s postwar efforts. But it would be too easy to consider Nazi Agent as a dismissible “B” production or simple studio programmer, undoubtedly paired on a double-bill with some other forgotten gem from this era. Besides creating ample tension and directing Veidt in two strong central performances, Dassin shows that he’s technically capable by delivering the best use of identical twins onscreen outside of David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers (1988). Consider how Dassin uses convincing doubles and split-screen effects to render two version of Veidt in the same shot (a breeze today with CGI, a challenge in 1942). The director doesn’t limit himself to a single angle, either; Becker and von Detner appear together in various profiles, with one in the foreground and the other in the background, and other ways that allow the viewer to accept their presence together onscreen. It’s an easy detail to overlook precisely because it’s so convincing.

Of course, Nazi Agent doesn’t have the biting commentary, chiaroscuro style, or cynicism of Dassin’s postwar efforts. But it would be too easy to consider Nazi Agent as a dismissible “B” production or simple studio programmer, undoubtedly paired on a double-bill with some other forgotten gem from this era. Besides creating ample tension and directing Veidt in two strong central performances, Dassin shows that he’s technically capable by delivering the best use of identical twins onscreen outside of David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers (1988). Consider how Dassin uses convincing doubles and split-screen effects to render two version of Veidt in the same shot (a breeze today with CGI, a challenge in 1942). The director doesn’t limit himself to a single angle, either; Becker and von Detner appear together in various profiles, with one in the foreground and the other in the background, and other ways that allow the viewer to accept their presence together onscreen. It’s an easy detail to overlook precisely because it’s so convincing.

When watching Nazi Agent today, viewers must approach the material with the above historical considerations in mind, accepting the film on its own terms. Most pictures released in the early 1940s were shaped by World War II in some manner, with evidence of this appearing in both direct and indirect ways onscreen. It’s perhaps most important to note that Nazi Agent was in production in November of 1941, before the attack on Pearl Harbor, and then wrapped production not long after the following month. From that perspective, MGM had committed to a staunch anti-Nazi message before Pearl Harbor, before the U.S. government asked Hollywood to use their cultural influence to support the war. This makes Nazi Agent part of a rare few Hollywood films of the prewar era in isolationist America that dared speak out against Nazism. After the U.S. joined the war, however, the film fit easily into a new initiative to support the military by selling war bonds, a request surely added onto the end title card in post-production.

Nazi Agent becomes a stirring drama thanks to Veidt’s performance, as well as the parallels between his life and his onscreen character. When Becker strikes a deal with a Nazi to sacrifice himself and protect Kaaren from reprisals, he says, “I am only one, one of 130 million Americans who together with all the good people of the world are rising to crush you and everything you stand for, once and for all.” The character’s speechifying patriotism may seem earnest and derived from Hollywood’s growing number of message films and propaganda from this period, but it’s delivered with an undeniable authenticity and passion in Veidt’s eyes. Whereas wartime Hollywood propaganda was influenced or encouraged by the U.S. government, message films like this one came from a place of Hollywood’s genuine disdain for Nazism. Capably made by Dassin, signaling a promising new talent in the years to come, Nazi Agent is far too easy to disregard as nonessential next to the other output by the talent involved. Beyond being an entertaining spy yarn, it reflects the lives of those involved, the Nazis working in America and Hollywood, and therein remains a fascinating and significant piece of Hollywood history.

Sources:

Allen, Jerry C. Conrad Veidt: From Caligari to Casablanca. Boxwood Press, 1987.

Dick, Bernard F. The Star-Spangled Screen: The American World War II Film. The UniversityPress of Kentucky, 1985.

Koppes, Clayton R. and Gregory D. Black. Hollywood Goes to War: How Politics, Profits and Propaganda Shaped World War II Movies. University of California Press, 1987.

McLaughlin, Robert L. and Sally E. Parry. We’ll Always Have the Movies: American Cinema During World War II. The University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

Urwand, Ben. The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler. Yale University Press, 2013.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review