The Definitives

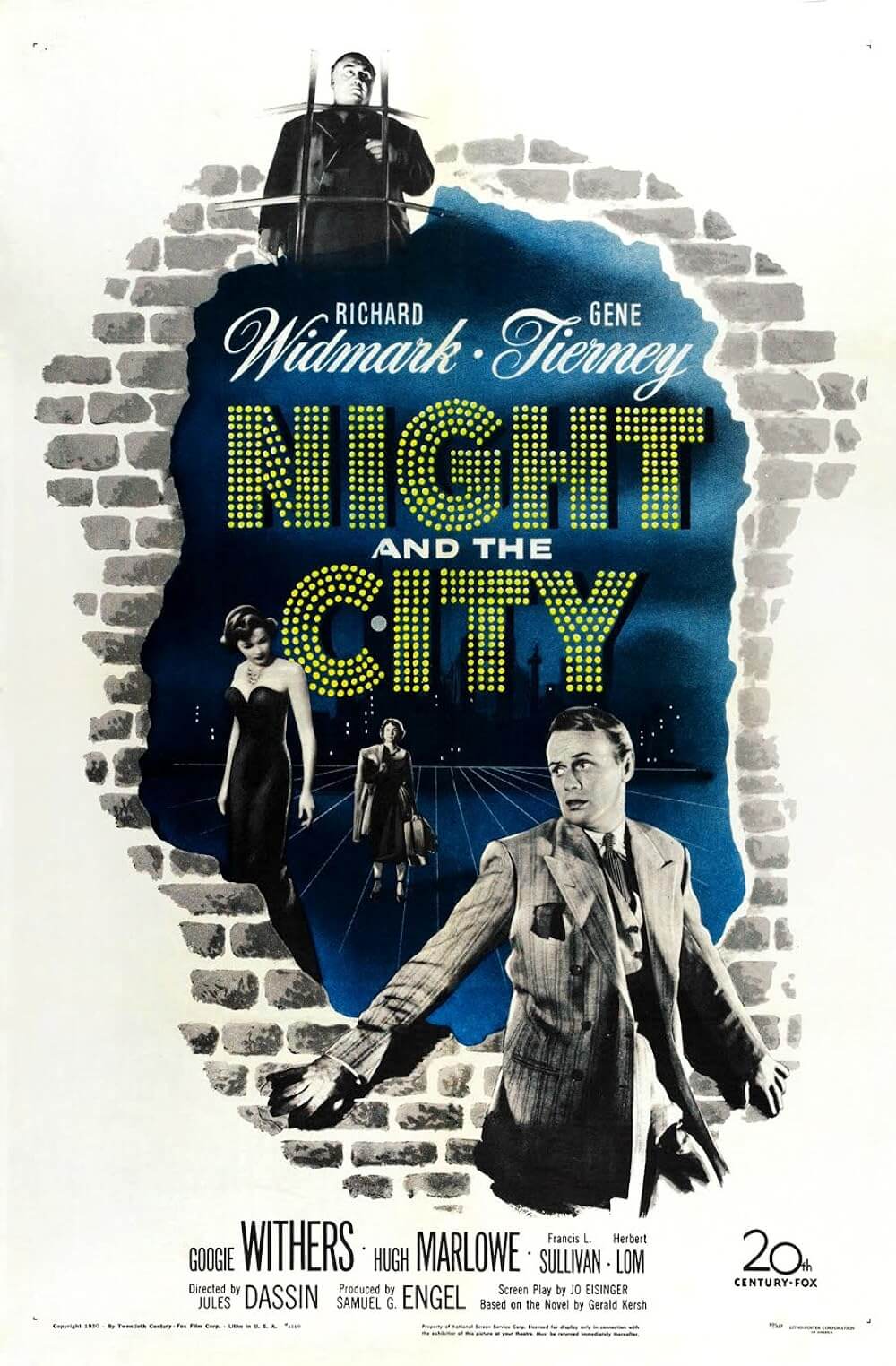

Night and the City

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Night and the City opens with narration over shots of London at night. “Night and the city,” says an American voice. “The night is tonight, tomorrow night, or any night. The city is London.” More specifically, the nocturnal Soho neighborhood known for gangs, its red light district, and rampant crime—a legendarily infected hub within London’s West End. Thomas de Quincey wrote of Soho at the beginning of the nineteenth century in Confessions of an English Opium Eater, whose title is suggestive enough, that Soho was “darkness… and desolation” where a flâneur could wander at night, collapse from hunger, and find reprieve in the bosom of an underage prostitute. Gerald Kersh’s source novel for Night and the City was his third, written in 1938, but not published until 1946 due to World War II. Kersh described the story’s protagonist, Harry Fabian, played with slimy glee by Richard Widmark, as a Soho “ponce” (what today we would call a pimp). Fabian stands as a classical film noir character, doomed from the outset, and ever-pursued by his desire to get ahead, until his scheming catches up with him in the worst ways. Produced by Daryl F. Zanuck at Twentieth Century Fox and shot in England, the film delivers a Dickensian cityscape through pointedly Hollywood film noir storytelling.

The film’s opening narration, spoken by its director Jules Dassin, recalls how filmmaker Carol Reed opened his picture The Third Man (1949) in much the same way. This will not be the last comparison made to Reed’s film in this appreciation, as both titles suggest parallel themes of realism and expressionism, and both go about achieving them in similar ways. Dassin and Reed each harnesses the reality of their postwar underworld by shooting on location and exposing horrendous crimes, yet their films have been masterfully crafted with chiaroscuro shadows and off-kilter angles, accentuating the undercurrent of darkness beneath these settings even further. But where The Third Man is playful, even the title of Night and the City is “pure, hard poetry,” as Andrew Pulver observed in his volume for the British Film Institute. To be sure, Dassin’s cinematographer Max Greene shoots rich street photography recalling that of Weegee. The locations range from flophouses to seamy flats, dive bars to alleyways. The familiar setting of London becomes a strange and unseemly environment. Transforming a generalized setting into a sordid, alternate backdrop was a common theme in film noir, and another connection between Night and the City and The Third Man, which takes place in Vienna. Likewise, both films also use the crumbled post-World War II milieu to their advantage. Reed’s Vienna had collapsed buildings and mounds of wreckage; Dassin’s postwar London features an effort to tear down toppled buildings and reconstruct.

When Kersh’s novel was released in 1946, producer Charles K. Feldman paid $45,000 for the film rights and hired former police reporter Jo Eisinger to write the script. Feldman had negotiated with Jacques Tourneur (Out of the Past, 1947) to direct, but ultimately Feldman’s financing fell through. The production, including the book-to-film rights and Eisinger’s script, was sold to Zanuck at Fox. Because the film took place in London, Zanuck set up production at Fox’s U.K. office to avoid any questions about postwar currency regulation. The Anglo-American Film Agreement would not allow U.S. films to draw too much away from the U.K. box office, so Zanuck used British facilities and crewmembers, but reserved key positions (leading man, director) for U.S. talent. Zanuck dispatched Dassin overseas, knowing the director was a member of the Communist Party since 1939; the studio wanted Dassin out of the country before he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Dassin remarked, “Zanuck pushed this book in my hand, and said, ‘You’re leaving, you’re getting out of here. You’re going to London and you’re going to make this, because this is probably the last picture you’re ever going to make.'” However, if given a choice, Dassin later claimed he would not have fled to avoid giving testimony. Nevertheless, Night and the City would be Dassin’s last film shot in the United States until Uptight in 1968.

When Kersh’s novel was released in 1946, producer Charles K. Feldman paid $45,000 for the film rights and hired former police reporter Jo Eisinger to write the script. Feldman had negotiated with Jacques Tourneur (Out of the Past, 1947) to direct, but ultimately Feldman’s financing fell through. The production, including the book-to-film rights and Eisinger’s script, was sold to Zanuck at Fox. Because the film took place in London, Zanuck set up production at Fox’s U.K. office to avoid any questions about postwar currency regulation. The Anglo-American Film Agreement would not allow U.S. films to draw too much away from the U.K. box office, so Zanuck used British facilities and crewmembers, but reserved key positions (leading man, director) for U.S. talent. Zanuck dispatched Dassin overseas, knowing the director was a member of the Communist Party since 1939; the studio wanted Dassin out of the country before he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Dassin remarked, “Zanuck pushed this book in my hand, and said, ‘You’re leaving, you’re getting out of here. You’re going to London and you’re going to make this, because this is probably the last picture you’re ever going to make.'” However, if given a choice, Dassin later claimed he would not have fled to avoid giving testimony. Nevertheless, Night and the City would be Dassin’s last film shot in the United States until Uptight in 1968.

Around that time, another blacklisted Hollywood director, Edward Dmytryk, who accepted jail time for his Communist status, testified at HUAC hearings against Dassin and the director was officially blacklisted. Not that it was a surprise. Dassin began in the theater—politicized, radical theater to be specific—working with the Yiddish Proletarian Theater, also known as ARTEF, in New York. He became a member of the American Communist Party after seeing Clifford Odet’s Waiting for Lefty in 1935. Working in the Federal Theater Project, which had a decidedly left-wing political agenda with famous productions like The Cradle Will Rock, Dassin soon found himself out of work when the state project’s funding was canceled by Congress in 1939. He transitioned to motion pictures and secured a position with RKO as a “watcher” of directors; among the filmmakers he watched was Alfred Hitchcock, from whom he learned the craft of directing. Dassin went on to helm several features for MGM, including Nazi Agent (1942), The Canterville Ghost (1944), and A Letter for Evie (1946). A falling out with Louis B. Mayer left Dassin fired from MGM. Soon enough, he began to work with producer Mark Hellinger, who, like Dassin, was Jewish, leaned far to the left, and was quite often a radical. Alongside Hellinger, Dassin made his most dynamic U.S. films, beginning with Brute Force (1947) and then The Naked City (1948). With those films, Dassin made a name for himself as a noir director; he was hired by Zanuck to make Thieves’ Highway (1949) at Fox. He and Zanuck would collaborate one last time on Night and the City.

Shooting took place over the summer of 1949, beginning in July, mostly overnights. Widmark was needed most nights for the shoot, meaning he rarely got back to the country cottage or Mayfair flat Twentieth Century Fox secured for him. Cameraman Max Greene, who was accustomed to shooting noirish stories with violent content (A Voice in the Night, 1946; So Evil My Love, 1948), flourished alongside his director, who was experienced in location shooting after The Naked City in New York. Greene was a Berlin-born cinematographer active since the 1920s and originally named Mutz Greenbaum; he left Germany for the U.K. in 1931 and changed his name to Max Greene, a common practice for many German émegrés in the industry. Percy Hoskins, a 1950s crime reporter in England, served the production as location manager, bringing Dassin to all the seedy nightspots he learned about as a newspaper man. Hoskins found incredible, authentic locations in the filthiest parts of town. Dripping alleyways with neon signs, walk-up flats, sweaty basement dives, and atmospheric streets. Greene shot them all with a combination of expert chiaroscuro and the fast-paced, documentary-style realism Dassin later displayed on Rififi (1955).

Shooting took place over the summer of 1949, beginning in July, mostly overnights. Widmark was needed most nights for the shoot, meaning he rarely got back to the country cottage or Mayfair flat Twentieth Century Fox secured for him. Cameraman Max Greene, who was accustomed to shooting noirish stories with violent content (A Voice in the Night, 1946; So Evil My Love, 1948), flourished alongside his director, who was experienced in location shooting after The Naked City in New York. Greene was a Berlin-born cinematographer active since the 1920s and originally named Mutz Greenbaum; he left Germany for the U.K. in 1931 and changed his name to Max Greene, a common practice for many German émegrés in the industry. Percy Hoskins, a 1950s crime reporter in England, served the production as location manager, bringing Dassin to all the seedy nightspots he learned about as a newspaper man. Hoskins found incredible, authentic locations in the filthiest parts of town. Dripping alleyways with neon signs, walk-up flats, sweaty basement dives, and atmospheric streets. Greene shot them all with a combination of expert chiaroscuro and the fast-paced, documentary-style realism Dassin later displayed on Rififi (1955).

Between the time filming wrapped in November 1949 and Night and the City hit theaters the following June, the studio produced two different cuts, an edit for release in the U.K. with music by Benjamin Frankel, and another cut released in America and internationally with a score by Franz Waxman. During the editing process, Dassin only had contact with the editors via telephone and had no knowledge that two cuts would be produced; he later remarked the studio had avoided him “like the plague,” no doubt due his blacklisted status. Zanuck hired two editors to cut the film, Nick De Maggio and Sidney Stone. Stone produced the 101-minute British version and De Maggio, who had worked with Dassin before on Thieves Highway, cut the 96-minute American version. The two scores play a major role in differentiating the two versions, as Frankel’s score is far less intense and suspenseful than Waxman’s. Waxman had worked for Fritz Lang on Fury (1936), Hitchcock on Rebecca (1940) and Rear Window (1954), and Billy Wilder on Sunset Blvd. (1950) and Stalag 17 (1953). Waxman knew how to compose music for darker thrillers. Frankel was best suited to lighter, more bubbly fare like Alexander Mackendrick’s The Man in the White Suit (1951) and Anthony Asquith’s The Importance of Being Earnest (1952). Likewise, the opening narration is spoken with a British accent in the British version, and an American accent in the American version.

The film opens as Fabian races away from a villain, having weaseled his way out of the £5 he owes for his latest failed scheme. And where does Fabian run? Where he always runs, to Mary (Gene Tierney), his sweetheart who can’t help but concede when he begs for cash. She helps him, as she always does, and as quick as he came rushing in he goes back out into the night. Fabian works on commission at the Silver Fox, a nightspot whose owners Phil Nosseross (Francis L. Sullivan) and wife Helen (Googie Withers) pay him to hustle suckers into their club. While out spotting dupes, Fabian visits a wrestling match operated by the underworld boss Kristo (Herbert Lom), who promotes all London wrestling. There, Kristo’s father, the aged world-famous Greco-Roman wrestler Gregorius (Stanislaus Zbyszko), cannot stand to watch Kristo’s wrestler The Strangler (Mike Mazurki) engage in today’s artless wrestling style. Greco-Roman wrestling was once an Olympic sport and allowed holds only above the waist; it required more skill than today’s punchy, savage show-wrestling. Gregorius would rather train Nikolas (Ken Richmond), a young student of Greco-Roman wrestling, and resolves to leave the match, much to Kristo’s disappointment. Fabian sees his chance and takes it, appealing to Gregorius’ pride. His plan: become London’s new wrestling promoter with Gregorius as his figurehead. But he needs £400 as starter money. When Fabian tries to borrow money from Phil, he’s laughed at and, based on Helen’s suggestion, he’s told if he can raise £200, Phil will match it. Phil only makes the offer because he knows Fabian can’t get it.

The film opens as Fabian races away from a villain, having weaseled his way out of the £5 he owes for his latest failed scheme. And where does Fabian run? Where he always runs, to Mary (Gene Tierney), his sweetheart who can’t help but concede when he begs for cash. She helps him, as she always does, and as quick as he came rushing in he goes back out into the night. Fabian works on commission at the Silver Fox, a nightspot whose owners Phil Nosseross (Francis L. Sullivan) and wife Helen (Googie Withers) pay him to hustle suckers into their club. While out spotting dupes, Fabian visits a wrestling match operated by the underworld boss Kristo (Herbert Lom), who promotes all London wrestling. There, Kristo’s father, the aged world-famous Greco-Roman wrestler Gregorius (Stanislaus Zbyszko), cannot stand to watch Kristo’s wrestler The Strangler (Mike Mazurki) engage in today’s artless wrestling style. Greco-Roman wrestling was once an Olympic sport and allowed holds only above the waist; it required more skill than today’s punchy, savage show-wrestling. Gregorius would rather train Nikolas (Ken Richmond), a young student of Greco-Roman wrestling, and resolves to leave the match, much to Kristo’s disappointment. Fabian sees his chance and takes it, appealing to Gregorius’ pride. His plan: become London’s new wrestling promoter with Gregorius as his figurehead. But he needs £400 as starter money. When Fabian tries to borrow money from Phil, he’s laughed at and, based on Helen’s suggestion, he’s told if he can raise £200, Phil will match it. Phil only makes the offer because he knows Fabian can’t get it.

And so, Fabian must raise £200. But all of his shady contacts fall through, until Helen, fed up with her husband, agrees to give Fabian the money if he secures her a license to open her own club. Phil quickly puts together that Fabian only secured the funds because Helen pawned the fox fur he recently gave her. Betrayed, Phil wants revenge and goes along with Fabian’s scheme; knowing Kristos will not let Fabian’s plan proceed, he waits for the right moment to strike. Meanwhile, Fabian sets up his own wrestling shop with Gregorius as his partner, but Phil suddenly refuses to back him, claiming there’s no audience for Greco-Roman wrestling. Fabian resolves to attract viewers by orchestrating a grudge match between Nikolas and The Strangler, brilliantly arranged by concocting an ersatz quarrel between the two. And for a brief moment, Fabian feels on top of the world. He seems to have an edge on everybody and a surefire sold-out event on the horizon. To pay The Strangler for the match, Fabian returns to Phil—who takes down Fabian at his peak. He refuses Fabian the money, another lousy £200. Not 2 million or even 2 thousand. Just £200. Phil tells Fabian that he’s been feeding Kristo information about Fabian’s scheme to take over the wrestling market. But now Kristo will be after him. “You’ve got everything,” Phil says. “But you’re a dead man.”

Still desperate to secure £200 to pay The Strangler for the proposed grudge match and earn a fortune, Fabian rushes to Mary’s and throws her place apart looking for her savings. “You’re killing me,” she cries, and then foretells, “And you’re killing yourself.” Just as Fabian returns to the wrestlers at his shop, he finds The Strangler drunk and picking a fight with Nikolas. All at once, The Strangler throws Nikolas and breaks his wrist, and Gregorius steps in to put The Strangler down. The two titans wrestle in a savage battle, which, just as Kristo arrives to see the finale, Gregorius wins—or rather, Greco-Roman wrestling wins. But Fabian’s tight-knit plans unravel when Gregorius, having mortally over-exerted himself, stumbles out of the ring and dies in Kristo’s arms. Fabian runs for it, and Kristo puts out a £1,000 bounty for information leading to his capture. Fabian scrambles through ruined buildings and reconstructions sites. His former friends sell him out for the bounty. He runs and runs, before stumbling down to a shack near the Thames, the shop of black marketer Anna O’Leary (Maureen Delaney). Mary finds him there. He concedes to his own doom and, only in these last moments, realizes what he’s become and how poorly he’s treated her. To pay her back, he resolves to carry out his first truly “foolproof” idea—he takes to the street and races toward Kristo, whom he can see on the Hammersmith Bridge. He shouts as if Mary sold him out, hoping that Kristo will give her the £1,000 reward. In a split second, The Strangler grabs Fabian, unceremoniously breaks his neck, and throws him into the river.

Still desperate to secure £200 to pay The Strangler for the proposed grudge match and earn a fortune, Fabian rushes to Mary’s and throws her place apart looking for her savings. “You’re killing me,” she cries, and then foretells, “And you’re killing yourself.” Just as Fabian returns to the wrestlers at his shop, he finds The Strangler drunk and picking a fight with Nikolas. All at once, The Strangler throws Nikolas and breaks his wrist, and Gregorius steps in to put The Strangler down. The two titans wrestle in a savage battle, which, just as Kristo arrives to see the finale, Gregorius wins—or rather, Greco-Roman wrestling wins. But Fabian’s tight-knit plans unravel when Gregorius, having mortally over-exerted himself, stumbles out of the ring and dies in Kristo’s arms. Fabian runs for it, and Kristo puts out a £1,000 bounty for information leading to his capture. Fabian scrambles through ruined buildings and reconstructions sites. His former friends sell him out for the bounty. He runs and runs, before stumbling down to a shack near the Thames, the shop of black marketer Anna O’Leary (Maureen Delaney). Mary finds him there. He concedes to his own doom and, only in these last moments, realizes what he’s become and how poorly he’s treated her. To pay her back, he resolves to carry out his first truly “foolproof” idea—he takes to the street and races toward Kristo, whom he can see on the Hammersmith Bridge. He shouts as if Mary sold him out, hoping that Kristo will give her the £1,000 reward. In a split second, The Strangler grabs Fabian, unceremoniously breaks his neck, and throws him into the river.

Along with alternate edits of the same scene and a generally more manipulative version of Fabian in the American cut, the endings also differ. The British version even suggests a happy ending. After Fabian is killed, there’s an additional scene where Adam (Hugh Marlowe), Mary’s concerned niceguy neighbor, rushes to comfort Mary; he takes her hand and they walk off together in the distance, the scene implying the two will live happily ever after. This scene doesn’t exist in the American version. Once the Strangler tosses Fabian’s corpse into the Thames, Kristo flicks a cigarette toward his body: The End. It’s among the bleakest endings ever conceived for a film noir or otherwise in this era. And yet, it aligns perfectly with film noir titles of the period, many of which ended with the amoral hero meeting his demise. Double Indemnity (1944) saw Fred MacMurray’s character doomed to either die of a gunshot wound or survive and face the gas chamber. John Garfield also faced execution for his crimes at the end of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946). Out of the Past ended with Robert Mitchum’s character betrayed, shot, and later found dead in a burning car wreck. In the truest form of film noir, the unscrupulous protagonist meets his demise in the American cut of Night and the City. Not long before his death in 2008, Dassin said he preferred the American edit.

Critical reactions were just as divisive as the two edits. Despite Zanuck catering to British audiences with a carefully modulated cut, the British critics were unenthusiastic. “Dassin remains a tourist in London,” said the critic for the Monthly Film Bulletin. Dilys Powell wrote in The Sunday Times, “It is about as British as Sing Sing and will do the British cinema nothing but harm.” Other critics called Night and the City inaccurate geographically, though all exteriors were shot on location. “The real flavor of London is missing,” wrote the Star critic. Elsewhere, Kersh despised the film and deemed it unfaithful, repeatedly complaining that he was paid £10,937 per word, for the four-word title. Dassin later admitted that he never read the novel: “There was no time. We had to get the script going, and I was under pressure.” When he finally read it, he conceded, “It was a whole other story!” Aside from character names and the London underworld setting, the film and novel bear little resemblance to one another. The differences are many and, in some cases, significant. In Kersh’s book, Fabian is a British pimp who often claims to be American. He lives off the earnings of his prostitute girlfriend and blackmails her clients; generally, he’s a much nastier sort of criminal and, at one point, even tries to sell his girlfriend to a sex trafficker. Unlike the film, the book’s Fabian doesn’t meet a film noir demise; rather, he’s spared a death-by-wrestler when he’s detained by authorities, who are cleaning up the streets in anticipation of the coronation ceremony for the British monarch. In the film, Kristo and the entire climax were pure inventions of Jo Eisinger.

Critical reactions were just as divisive as the two edits. Despite Zanuck catering to British audiences with a carefully modulated cut, the British critics were unenthusiastic. “Dassin remains a tourist in London,” said the critic for the Monthly Film Bulletin. Dilys Powell wrote in The Sunday Times, “It is about as British as Sing Sing and will do the British cinema nothing but harm.” Other critics called Night and the City inaccurate geographically, though all exteriors were shot on location. “The real flavor of London is missing,” wrote the Star critic. Elsewhere, Kersh despised the film and deemed it unfaithful, repeatedly complaining that he was paid £10,937 per word, for the four-word title. Dassin later admitted that he never read the novel: “There was no time. We had to get the script going, and I was under pressure.” When he finally read it, he conceded, “It was a whole other story!” Aside from character names and the London underworld setting, the film and novel bear little resemblance to one another. The differences are many and, in some cases, significant. In Kersh’s book, Fabian is a British pimp who often claims to be American. He lives off the earnings of his prostitute girlfriend and blackmails her clients; generally, he’s a much nastier sort of criminal and, at one point, even tries to sell his girlfriend to a sex trafficker. Unlike the film, the book’s Fabian doesn’t meet a film noir demise; rather, he’s spared a death-by-wrestler when he’s detained by authorities, who are cleaning up the streets in anticipation of the coronation ceremony for the British monarch. In the film, Kristo and the entire climax were pure inventions of Jo Eisinger.

American critics were divided, with the film’s greatest admirers citing Dassin’s impressive technical display, his use of shadow and frenzied on-location shooting. Then again, the Americans had no idea that for Fabian to sprint from Waterloo to Hammersmith Bridge in a matter of moments was laughable (it’s about a 40-minute walk and a 15-minute car ride). No matter, since realism was very much the British priority at the time, whereas style was more important to both American and French audiences. Indeed, the French critics, who had celebrated Dassin’s output since The Naked City, received Night and the City as another revelation from the director. François Truffaut, writing in Arts magazine, called it “the best of Dassin’s films” and said it demonstrated “true epic inspiration”—that is, until most French critics were later drawn to Dassin’s French-language masterpiece Rififi (which Truffaut later called “The best crime film I have ever seen.”). The French critics also celebrated Night and the City for characteristics that would later become popular during the French New Wave. Improvisational location camerawork and ad-libbed moments from Widmark, such as Fabian drumming his enthusiasm on the Silver Fox’s drum set, demonstrated that Dassin could take rather familiar material and, through his auteuristic perspective, reformat the experience into something wholly unique.

Widmark had already made his mark in film noir, and earned himself an Academy Award nomination playing the maniacal villain in 1947’s Kiss of Death. A political liberal much like his director, the otherwise easygoing Widmark was a wiry-looking figure with sharp movements and a skeletal, expressive face. He played brash, energetic, and sometimes hysterical characters, each with the actor’s signature laugh. Whether he dialed up the snicker for his bloodthirsty Kiss of Death character Tommy Udo, or transformed it into a boastful cackle, as he does in Pickup on South Street (1955), Widmark’s laughs are always memorable. In Night and the City, he laughs with outward confidence, often with an undercurrent of insecurity, but more often with a blind enthusiasm that whatever scheme he’s cooking will work out fine. One critic remarked, “he adds demonic rage to the role.” Ever sweating and desperate to prove himself, Widmark’s character has animal desperation to him, as though he’s been cornered and will soon be trapped. “Harry is an artist without an art,” says Adam. “A man very unhappy… groping for the right level, the means with which to express himself.” The film even gives Fabian a backstory to enhance his impending, tragic doom. At one point, Mary reflects on a photo of them from a while back. “Remember them, Harry? Nice people.” Since then, Harry has been running, scheming, trying to get ahead. In some ways, he perpetuates the danger around himself; but there’s also a reference to his troubled backstory running from “Welfare officers, thugs, my father…” But Fabian is also a cruel, unfeeling bastard who takes every advantage he can. And yet, when Fabian is on the run, Widmark breaks the character down into a trembling dog as he ponders his death.

Widmark had already made his mark in film noir, and earned himself an Academy Award nomination playing the maniacal villain in 1947’s Kiss of Death. A political liberal much like his director, the otherwise easygoing Widmark was a wiry-looking figure with sharp movements and a skeletal, expressive face. He played brash, energetic, and sometimes hysterical characters, each with the actor’s signature laugh. Whether he dialed up the snicker for his bloodthirsty Kiss of Death character Tommy Udo, or transformed it into a boastful cackle, as he does in Pickup on South Street (1955), Widmark’s laughs are always memorable. In Night and the City, he laughs with outward confidence, often with an undercurrent of insecurity, but more often with a blind enthusiasm that whatever scheme he’s cooking will work out fine. One critic remarked, “he adds demonic rage to the role.” Ever sweating and desperate to prove himself, Widmark’s character has animal desperation to him, as though he’s been cornered and will soon be trapped. “Harry is an artist without an art,” says Adam. “A man very unhappy… groping for the right level, the means with which to express himself.” The film even gives Fabian a backstory to enhance his impending, tragic doom. At one point, Mary reflects on a photo of them from a while back. “Remember them, Harry? Nice people.” Since then, Harry has been running, scheming, trying to get ahead. In some ways, he perpetuates the danger around himself; but there’s also a reference to his troubled backstory running from “Welfare officers, thugs, my father…” But Fabian is also a cruel, unfeeling bastard who takes every advantage he can. And yet, when Fabian is on the run, Widmark breaks the character down into a trembling dog as he ponders his death.

Opposite Widmark was Gene Tierney, a popular Hollywood figure and established star of Laura (1944) and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947). Tierney often played women with an unstable element to them, perhaps because she, too, felt unstable; she had long suffered from manic depression and endured a tumultuous series of treatments at psychiatric facilities beginning in 1954. After shock treatments (the use of which she would later rally against), a suicide attempt, and nearly a decade of personal troubles, Tierney returned to film, if only periodically, whenever she felt the stress was not too much to bear. Dassin also hand-picked Polish wrestler Stanislaus Zbyszko to play Gregorius the Great, despite Zanuck’s insistence that Dassin should just find a muscular actor to fill the role. The director vaguely remembered watching a Zbyszko bout from his youth, unaware that Zbyszko had helped shape the worldwide wrestling scene as a Greco-Roman devotee and world champion in 1925. The director asked his sports reporter friend to trace Zbyszko, and the long-retired figurehead was located on a farm in New Jersey. Alongside Zbyszko, lesser-known real-life wrestler Mike Mazurki was hired to play The Strangler; Mazurki, however, had already worked on a few Hollywood films, including The Canterville Ghost with Dassin. Still powerful and even unbearable today is the well-acted wrestling bout between Gregorius and the Strangler. Though Gregorius prefers a more classical style of wrestling, the brawl descends into eye-gouging, callous jabs, and piercing handfuls of flesh among the usual bear hugs and body slams.

But Night and the City relies most on Widmark, whose Fabian stands as an assemblage of hustler cues, from trying to lift loose cash out of Mary’s purse to constantly sweating, quite literally, about the pressure that’s bearing down on him. “You can’t go on forever,” says Mary, “always running, always in a sweat.” Fabian also always has an angle. In a tragic subplot, he makes that deal with Helen to secure her a license for her own club. Fabian, ever the scoundrel, sells her a forged license. When Helen leaves Phil in a harsh scene, saying he disgusts her and she will never come back to him, she finally lives her dream of opening her own club. But she quickly discovers the license Fabian sold her is a fake. She has no choice but to return to Phil, who has since shot himself out of despair. It’s one of the story’s turns that renders Fabian impossible to redeem, no matter how hard he tries in the last scene. As a result, historians who associated Fabian to Dassin, because Dassin avoided HUAC just as Fabian runs from gangsters, rely on a thin tissue to connect their arguments. Perhaps Dassin did feel a certain kinship with his film’s anti-heroic protagonist, which, intentionally or not, fuelled Night and the City‘s manic intensity through Widmark’s performance. Although, unlike Dmytryk (the sole member of the Hollywood Ten to give evidence to HUAC and admit his Communist standing), Dassin never returned to the U.S. for punishment. Fabian, however, clearly regrets and laments his crimes when, on the run, he stops for a brief reprieve at Anna O’Leary’s ramshackle boathouse. “Oh, Anna, the things I did,” he bemoans. Regardless of the initially parallel trajectories of Dassin and Fabian, they seem coincidental, superficial, and most certainly unplanned.

But Night and the City relies most on Widmark, whose Fabian stands as an assemblage of hustler cues, from trying to lift loose cash out of Mary’s purse to constantly sweating, quite literally, about the pressure that’s bearing down on him. “You can’t go on forever,” says Mary, “always running, always in a sweat.” Fabian also always has an angle. In a tragic subplot, he makes that deal with Helen to secure her a license for her own club. Fabian, ever the scoundrel, sells her a forged license. When Helen leaves Phil in a harsh scene, saying he disgusts her and she will never come back to him, she finally lives her dream of opening her own club. But she quickly discovers the license Fabian sold her is a fake. She has no choice but to return to Phil, who has since shot himself out of despair. It’s one of the story’s turns that renders Fabian impossible to redeem, no matter how hard he tries in the last scene. As a result, historians who associated Fabian to Dassin, because Dassin avoided HUAC just as Fabian runs from gangsters, rely on a thin tissue to connect their arguments. Perhaps Dassin did feel a certain kinship with his film’s anti-heroic protagonist, which, intentionally or not, fuelled Night and the City‘s manic intensity through Widmark’s performance. Although, unlike Dmytryk (the sole member of the Hollywood Ten to give evidence to HUAC and admit his Communist standing), Dassin never returned to the U.S. for punishment. Fabian, however, clearly regrets and laments his crimes when, on the run, he stops for a brief reprieve at Anna O’Leary’s ramshackle boathouse. “Oh, Anna, the things I did,” he bemoans. Regardless of the initially parallel trajectories of Dassin and Fabian, they seem coincidental, superficial, and most certainly unplanned.

The climactic chase and death of Fabian cannot help but remind us of the chase in The Third Man. Whereas Orson Welles’ Harry Lime raced through Vienna’s sewers to evade capture in a bravado sequence of high-contrast shadows and tilted angles, Fabian is hunted down by Kristo’s henchman with similar virtuosity. Green and Dassin unleash an impressive array of visual techniques and tension. Shots of Fabian on the run fuel paranoia as his shadows splash against walls and stretch along streets. We follow his silhouette and the sound of his footsteps, so desperate to escape as Widmark’s frantic motions show an uneasy loss of control. Dassin combined these expressive shots with a cinéma vérité style by setting up multiple cameras, allowing the editors to keep Widmark’s movements fluid and unbroken, even if such realism could be argued as incongruous next to the film noir expressionism of Night and the City. And yet, it never feels unnatural within the context of the film. Meanwhile, Kristo’s henchman drives around Picadilly Circus in shots reminiscent of the pre-robbery sequence from Gun Crazy (1950), complete with a car-mounted camera watching as Kristo’s man tells the underworld to keep a lookout for Fabian. Fabian meets his demise at the moment of dawn, which gave Dassin a small window in which to shoot. The director used six cameras to capture the scene from each angle. And despite many cuts throughout the scene, the moment was shot in one take. It’s a bleak scene, unforgivably violent.

Night and the City has that quality throughout—unforgiving, harsh, laden with the anticipation of ugly violence. Years later, when Dassin and Widmark died in the same month in 2008, Gilbert Adair used Night and the City to cover both artists in his obituary for The Independent, writing, “a notoriously un-cinegenic city… was transformed by warped angles and expressionistic light into a sinister chequerboard of villainy and terror.” Dassin transformed London in the same way David Lynch mutated Lumberton into a frightening underworld in Blue Velvet (1986). Dassin shot the Soho landscape and perverted it into a new cinematic topography. To draw another comparison between The Third Man and Night and the City, both Reed and Dassin filmed in otherwise unconnected locations in Vienna and London, and then edited together the most dynamic of them to create a more visually expressive cityscape. Though British critics faulted Dassin for not cataloging an accurate geographic map of London, he selected areas of the city that enhanced his film’s seediness. His choices would lead to Night and the City being widely praised. The BFI Companion to Crime, the Village Voice, the Guardian, Colin McArthur’s book Underworld USA, Foster Hirsch’s The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir, and countless other publications have named it Dassin’s finest work, even above Rififi, and perhaps the ultimate example of film noir.

Night and the City has that quality throughout—unforgiving, harsh, laden with the anticipation of ugly violence. Years later, when Dassin and Widmark died in the same month in 2008, Gilbert Adair used Night and the City to cover both artists in his obituary for The Independent, writing, “a notoriously un-cinegenic city… was transformed by warped angles and expressionistic light into a sinister chequerboard of villainy and terror.” Dassin transformed London in the same way David Lynch mutated Lumberton into a frightening underworld in Blue Velvet (1986). Dassin shot the Soho landscape and perverted it into a new cinematic topography. To draw another comparison between The Third Man and Night and the City, both Reed and Dassin filmed in otherwise unconnected locations in Vienna and London, and then edited together the most dynamic of them to create a more visually expressive cityscape. Though British critics faulted Dassin for not cataloging an accurate geographic map of London, he selected areas of the city that enhanced his film’s seediness. His choices would lead to Night and the City being widely praised. The BFI Companion to Crime, the Village Voice, the Guardian, Colin McArthur’s book Underworld USA, Foster Hirsch’s The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir, and countless other publications have named it Dassin’s finest work, even above Rififi, and perhaps the ultimate example of film noir.

Dassin’s status as an artist forced into isolation may have gained him, and Night and the City, sympathy after the film’s release—especially among his French admirers and devoted followers of the auteur theory. But no such association matters today. Of course, Dassin’s blacklisted status may have leaked into the film in unconscious ways; moments where Fabian scampers through reconstruction sites and hides in shadowy doorways cannot help but evoke the Red Scare paranoia in Hollywood, and the burning momentum that sent Dassin over the pond to film this picture. Even without those associations, Night and the City still explodes with the ferocity of Widmark’s urgent presence, his ruthless gloating and nervous laughter, and the way he grows enraged when not taken seriously. Dassin’s likewise urgent direction propels the film into an underworld that could only exist in cinema. Like Carol Reed before him, Dassin explores a postwar climate where desperate characters scrape by with unsavory deeds and sell their souls for a few bucks on the promise of a bigger payday. Fabian navigates that ever-enclosing film noir device of the city, which is truly an invented character in Dassin’s hands. Narrow passages, claustrophobic back alleys, and the pressure of someday making something of himself finally enclose on Harry Fabian, leaving him to carry out a final act of rare selflessness, though such an act could scarcely redeem him.

Bibliography:

Erickson, Glenn. “Expressionist Doom in Night and the City”, in Alain Silver and James Ursini (eds), Film Noir Reader. New York: Limelight, 1996.

McGilligan, Patrick (ed.). Tender Comrades: The Backstory of the Hollywood Blacklist. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Pulver, Andrew. Night and the City. (BFI Modern Classics). British Film Institute, London: 2010.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review