Bound

By Brian Eggert |

The Wachowski siblings, Andy and Lana, arrived on the cinematic map in 1996 with Bound, a thriller that contains many elements otherwise associated with exploitation fare. Though prior to this they had written material for Marvel Comics and collaborated on the (later heavily revised) screenplay for Assassins (1995), Bound was the Wachowskis’ first major project in which they maintained creative control. Leather, gangsters, harsh killings, and lesbian sexuality all play a role in this twisting neo-noir, yet those elements are elevated to considerable heights through the Wachowskis’ expert formal and clever narrative flourishes. Such components assemble to form an altogether surprising, titillating, and immersive experience rooted in the elemental notion of pure cinema. Certainly not within the mainstream, pointedly digital niche they have since carved out for themselves with The Matrix, Speed Racer, and Jupiter Ascending, their debut was smaller and in a way experimental. It was also carried along on a wave of playful, film-referential, and often humorous efforts to emerge in the mid-to-late 1990s, following the popularity and cultural explosion of Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction.

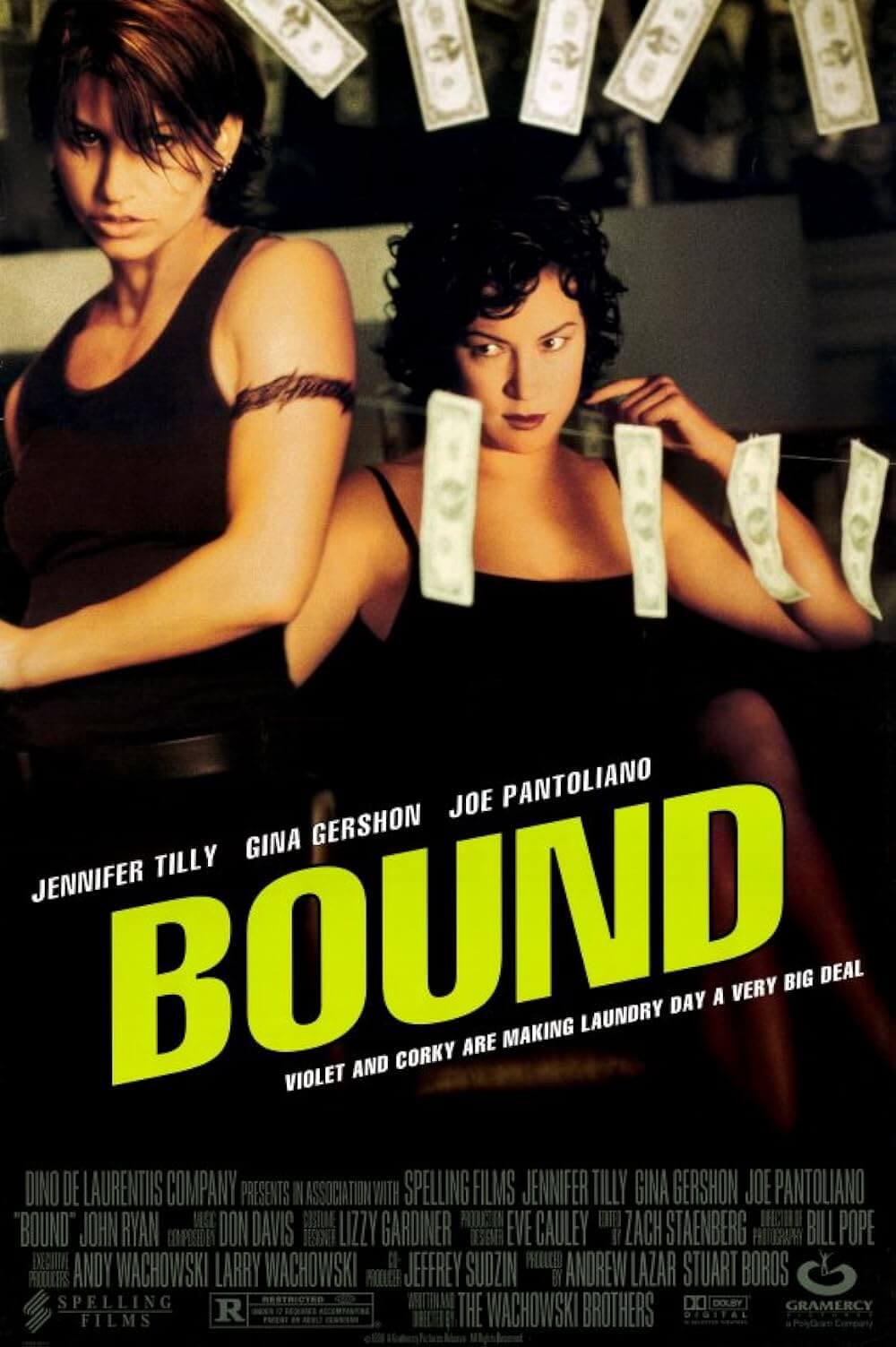

From the opening moments, the co-writers and directors show their film noir influence. The title appears in towering, stony letters that create deep and dramatic shadows. Then Gina Gershon appears, her face beaten, her mouth gagged, and her limbs tied. In an archetypal film noir structure, Gershon’s character, Corky, remembers back to how it all started: She’s in an elevator, hauling tools up to an apartment that she’s been hired to gut and restore. Clad in a leather jacket and tough expression, Corky watches as another woman enters the elevator. This is Violet (Jennifer Tilly), a more voluptuous and lusty woman whose Mafioso boyfriend, Caesar (Joe Pantoliano), follows behind her. But before Caesar enters the scene, Corky and Violet gaze at one another, the look long and penetrative, the moment deepened and almost humorous thanks to Don Davis’ jazzy score inflected with acoustic bass—recalling the comic juxtaposition of crime and jazz employed by David Lynch in Twin Peaks. Before long, Violet finds an excuse to visit and flirt with her new handyman neighbor, and in short order, they’re all over each other. All at once, Caesar enters and, despite the awkward scene, never suspects the two, lesbianism being so far outside of his norm, while he’s so blindly confident in his masculinity.

The film’s most knowing, tongue-in-cheek moments take advantage of the setup, delaying the homosexual coupling as long as possible through sexualized banter and imagery—just as film noirs from Double Indemnity (1944) to The Big Sleep (1946) had done in their heyday. Prior to their first embrace, Violet calls Corky over to extract a piece of jewelry she’s accidentally dropped down the sink (an old lonely housewife’s trick for seducing the local handyman). Confident, Corky smiles and says all she has to do is “open it up, tinker with it a bit, and fix it.” The Wachowskis’ frame shows Corky in the foreground, using her strong hands to manipulate the pipes and “find it,” while in the background we see only Violet’s legs and hips, the association unmistakable. Elsewhere, the Wachowskis incorporate sexuality into smaller details; for example, Corky plays the most vaginal looking of all instruments, the twanging mouth harp. After they finally bed one another, it’s almost disappointing that their comically erotic interplay lessens.

But there’s more going on in these scenes than just eroticism. Violet serves as Bound‘s resident femme fatale, who convinces Corky to assist her in ridding herself of Caesar, but not before stealing a pile of cash. The plan is that Corky and Violet will run away together. Corky is reluctant to give her trust, however; she just served a 5-year prison sentence for breaking and entering (the perfect crime for a lesbian criminal) after a previous double-cross. “I had a partner once,” Corky explains. “She fucked me.” And she’s even more hesitant to trust someone new when she learns Violet has been sleeping with one of Caesar’s associates, a man named Shelly (Barry Kivel), who has been skimming from the Chicago mob’s profits for years in a sum of over $2 million in cash—and most likely, it was Violet’s idea. When Caesar finds out, he and Johnnie (Christopher Meloni), the psychotic son of mob boss Gino Marzzone (Richard C. Sarafian), torture Shelly to find out where it’s been hidden. But in the process, Johnnie kills Shelly, getting the victim’s blood all over piles of cash. Caesar responds by socking Johnnie in the nose, a regretful decision that creates a potential rift between Caesar and Boss Marzzone.

Pantoliano is wonderful in Caesar’s frantic scenes of paranoia, tough but frightened and vulnerable, fretting over how to resolve his conflict with the boss’ son. Arriving home in a panic with stacks of blood-soaked cash, Caesar brings new meaning to the term “money launderer” when he washes and irons each bill individually, hanging them on strings with paper clips to dry. It’s unforgettable imagery. Meanwhile, Violet convinces Corky to steal the cash (her lockpick set hangs as earnings on her lobes) and make it look like Johnnie took the loot to set up Caesar, which would give Caesar no other option except to run. Because Caesar could never confront the boss’ son, right? But Violet underestimates how Caesar will react, how the strain has made him mad, and their carefully orchestrated plan falls apart to thrilling effect. Corky remains in the empty apartment next door, while Violet puts on for Caesar, who shockingly kills Johnnie and Marzzone in a fit of rage. Finally, Caesar and Violet must contend with suspicious cops and Marzonne’s top henchman, the sad and noble Micky (John Ryan), who carries a torch for Violet, as most men in the film do.

Tilly’s breathy, baby-talk voice served her well in Woody Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway (1994), where she earned an Oscar nomination in another role as a mobster’s girl. But she turns her signature sound into an almost Kathleen Turner-esque level of sultriness here. She’s incredibly convincing as a femme fatale, but it’s even more charming that the Wachowskis allow Violet and Corky to emerge from the film’s tense ordeal with a bag full of cash and no one to suspect them. Whereas Violet uses her sexuality as a weapon against men—Violet uses heterosexuality as a disguise—her only genuine affections are for Corky. Because we are familiar with the conventions of film noir, we cannot help but suspect Violet throughout. That she never double-crosses Corky is less a disappointment or failure to realize the character’s potential than a romantic jolt. This is where Bound becomes more than just a thriller, or a film that would exploit its lesbian characters; rather, it’s a sordid and violent love story. The Wachowskis present Corky as a strong woman who has been wounded by other women in the past, and rather than play out her repetitive and ill-fated lot, as so many film noir protagonists have, she finds true love. It’s a happy ending after all, where Tom Jones’ “She’s a Lady” blares on the soundtrack to comic, quirkily romantic effect.

More now than upon its initial release, the sexually exploitative element coursing through the film is reduced, as the credited Wachowski brother Larry underwent gender reassignment surgeries in the early 2000s and ultimately emerged as Lana Wachowski in 2008, just after the siblings’ release of Speed Racer. If nothing else, this suggests that Lana had some insight into female desire and could, therefore, relate to Corky and Violet in ways that another male filmmaker may not have been able to. Had Bound been the product of an exclusively heterosexual male pair of twentysomething college dropouts—which, on the surface, is what the Wachowskis appeared to be at the time—then the film might have reveled more in its kink, leather, and fringe sexuality. (Indeed, the Wachowskis seem to feel at home in the leathery lesbian bars of Bound, as a similar underground leather bar sequence occurs in The Matrix). Sex scenes between the two protagonists may have occurred more often throughout the picture, and perhaps without narrative purpose, if the Wachowskis were interested in exploiting lesbianism. And without Lana’s unique perspective, it’s worth hypothesizing that Bound simply would not have been as emotionally involving, passionate, and even endearing as it is.

On Bound, the Wachowskis also began their relationship with cinematographer Bill Pope, which lasted through The Matrix Revolutions. Pope’s fluid camera movements, angles, and framing impress throughout the picture, enhancing every moment. The whole film is shot within a small handful of interiors, yet Pope and the Wachowskis make excellent use of their space. Overhead angles that remind us of Hitchcock, tracking shots that zip along the length of a telephone cord to follow an important call, and body-mounted cameras augment Pope’s already slick, moody lighting and the Wachowskis’ stylish interiors. Even during the single lesbian sex scene, the viewer’s eyes are less concerned about the two nude lovers wrapped up in each other than the bravado way Pope’s camera moves in from a master shot, pans around them, and ends in close-up of their orgasmic faces. Bound is a story that would be fascinating even without an expert visual sense, but the Wachowskis take great care in their film’s visual luster. One of its most striking visuals is Caesar’s death scene, where he’s shot while standing in a pool of white paint, the red spatter dripping against the paint in a contrast that cannot help but recall the climax of Akira Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel.

In the boom of the postmodern and film-savvy cinema of the 1990s, the Wachowskis’ debut remains overlooked, if remembered fondly. Perhaps the sibling directors overshadowed their own film with their subsequent, decidedly larger efforts, beginning with The Matrix in 1999—a phenomenon that never would have happened without the enthusiastic response to their debut (although Bound wasn’t huge commercially, the independent release earned wide recognition within critical circles). Under the wrong circumstances or in another filmmaker’s hands, a film that employs passionate lesbian love and noir dialogue might have been corny and cheap. But with Bound, the Wachowskis use a gamut of filmic references and resources to tell a kind of cute, certainly romantic love story through graphic and violent neo-noir conventions. Brilliant as a skilled visual showcase worthy of Hitchcock or Brian De Palma, the film operates on several levels, from the emotional to the visceral. Today, the Wachowskis are known for delivering visual spectacles, but they often forget to build an adequate emotional foundation into their stories. Revisiting Bound, one cannot help but yearn for the Wachowskis to return to smaller-scale filmmaking, which applies pure cinema to limited locations and characters, and tests their considerable skill behind the camera.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review