The Matrix Revolutions

By Brian Eggert |

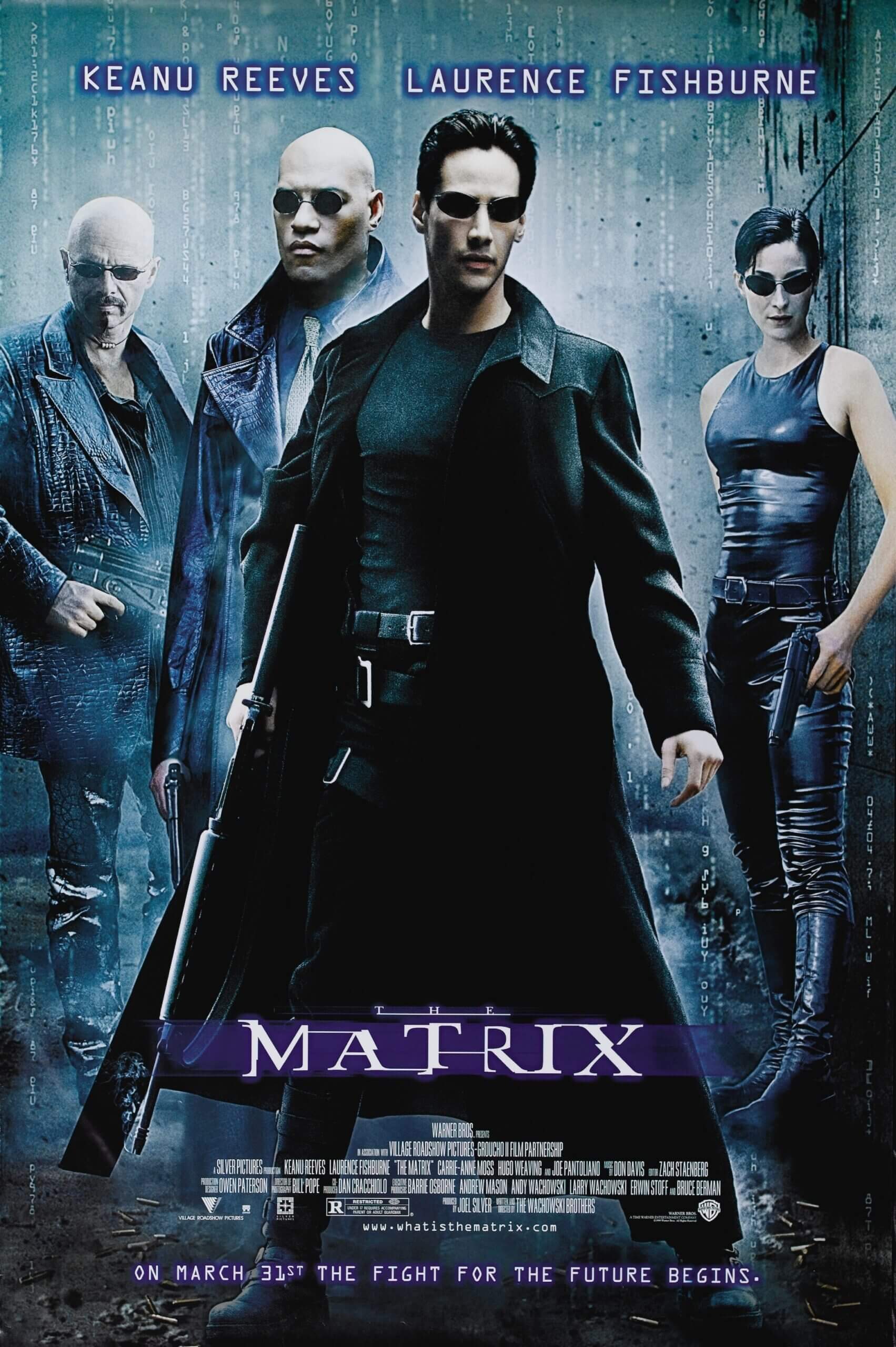

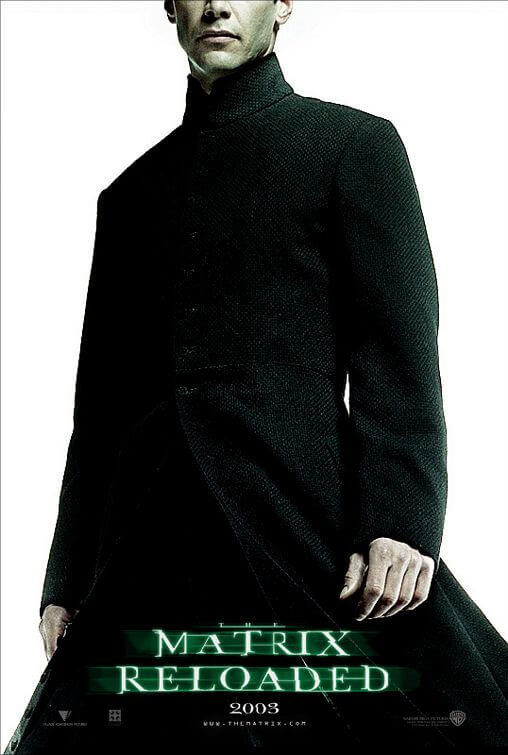

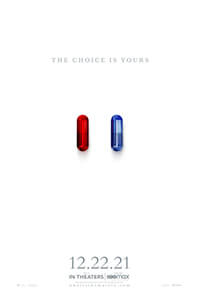

By the time The Matrix Revolutions arrived in theaters in November 2003, six months had passed since its predecessor, The Matrix Reloaded, received rampant negative word-of-mouth. The first sequel to 1999’s The Matrix made $278 million in domestic receipts and even more worldwide, but the general impression among audiences was dismissal and disappointment, if not outrage. A miasma floated over the final sequel going in, and as a result, this $150 million production earned back just $138 million in domestic receipts. And though its $427 million international haul ensured a hefty profit return on Warner Bros’ investment, the message was clear: audiences felt let down. Upon revisiting the film today, several individual sequences stand out as inspired action or well-composed visually, but the chaotic and overly complicated storytelling present in The Matrix Reloaded leads to a film that rushes toward a conclusion both anticlimactic and unsatisfactory. Although delivered through the Wachowski siblings’ expert technical execution, The Matrix Revolutions never lives up to its potential legacy.

The consensus among audiences and critics was that the series had begun as something new and original for blockbuster moviegoers, but beginning with Reloaded and even more so in Revolutions, the series ended as something predictable, overlong, and even hackneyed. In the New York Times, A.O. Scott observed, “There is very little that is tantalizing or suspenseful. The feeling of revelation is gone, and many of the teasing implications of ‘Reloaded’ have been abandoned.” Other critics remarked about the film’s excessive special FX and its attention on action over the thoughtful ideas of its predecessors. Carla Meyer wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle that the sequel was deadened by “computerized excess” and that “It’s as if the Wachowskis caught the George Lucas virus and decided that if it could be done with CGI, then by golly, it should be.” While it would be difficult to argue against such remarks, the sting of disappointment isn’t so sharp upon reflection.

Several plot strains (and subplots) were established in Reloaded and needed resolution in Revolutions. But while the Wachowskis forget several, two main conflicts take precedence: 1) The invasion of Zion by a robotic army of thousands, and 2) the emergence of a clone-crazed Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving) as a rogue program bent on the eradication of everything, real and virtual. In the second film, a Smith clone takes over the human Bane (Ian Bliss, doing an excellent impersonation of Weaving’s particular cadence), and through him, blinds the prophesied and now telekinetic hero Neo (Keanu Reeves). But at the end of The Matrix Reloaded, Neo encountered The Architect (Helmut Bakaitis), who told Neo that the savior myth is merely another elaborate means of control—a programmed reset button for The Matrix, less a genuine rebellion than a revolution in the orbital sense of the word. In those terms, The Matrix itself has been reloaded several times before. With each revolution, someone like Neo emerges as a hero, and each time, the machines wipe out Zion almost entirely.

However, this time, Smith’s maniacal, destructive presence allows Neo to negotiate a peace treaty with the machines’ baby-faced leader: Neo agrees to stop Smith if the machines agree to live in peace with humanity. In the end, the blind Neo engages Smith and his countless clones in a rainy Matrix cityscape, allows himself to be assimilated, and with some genuine Deus Ex Machina help from Babyface, destroys Smith and resets The Matrix. Through this conclusion, Neo becomes a Christ-like figure, carried off by machines as a revered martyr, and the human race and machines coexist in peace. Perhaps, then, the notion of a systematic process that has gone through several revolutions coincides with the film failing to explore the limitless possibilities of Neo’s power—a lasting complaint about both Reloaded and Revolutions. After all, Lawrence Fishburne’s Morpheus suggests in The Matrix that The One could do anything he put his mind to, so why doesn’t Neo simply crash the entire Matrix and release all humans by sheer force of will? Events in Reloaded and Revolutions infer that Neo was never meant to have true absolute power, thus negating the whole purpose of The Matrix.

Instead, Neo plays a role in a planned cycle compelling The One and his rebels to retaliate, only to be eliminated over and over throughout history. Any sense of freedom is an illusion. But still, at the end of Revolutions, Neo does indeed stop the cycle of revolutions and deliver peace, but this is less a result of his extraordinary power and more about the Smith situation providing the means for a peace treaty. Neo may not have lived up to the full potential hinted at during the first film. Still, that potential was an illusion—one audiences created for themselves—that any film could live up to the expectations set by The Matrix. If Neo was impervious to harm and could do anything he wanted, then there is no conflict. Philosophically speaking, Reloaded talks itself and Revolutions out of needing to live up to those expectations, but since that message is delivered in such an overly complex way, audiences missed it. Instead, viewers have only some impressive action sequences and neat ideas to cling to—propelled by characters who feel stripped of personality and exist on autopilot. Again, an argument could be made that this is by design, but it doesn’t act in service of the film’s legacy or ability to engage the emotions either.

Putting too much thought into Revolutions misses the point, which is to end the trilogy with a bang. Arguably, the Wachowskis deliver that bang through the two main conflicts mentioned above and their respective action setpieces. Unfortunately, this leaves Revolutions to be the least intelligent entry. The first significant action setpiece involves General Mifune (Nathaniel Lees, whose character is named after the legendary samurai actor Toshiro Mifune) and his small army of (very James Cameron-inspired) robotic gunner suits defending Zion from invading sentinels. It’s a long and involved sequence that spends too much time on a subplot about Kid (Clayton Watson), a gawky character desperate to prove himself. Meanwhile, Neo meets Smith in The Matrix and faces hundreds of Smith clones in a dark torrential downpour, but as he’s blind, Neo only sees in Matrix-vision, which amounts to a videogame view of the world. In concept, the sequence may have sounded neat, and it’s exciting stuff on a purely visceral level, but these are empty battles devoid of meaningful connections to the participating characters. Moreover, the sequel spends such little time inside The Matrix that you begin to wonder why “Matrix” was even in the title.

In the end, The Matrix Revolutions betrays its audience most not by failing to live up to the full potential of Neo’s prophecy or by dumbing down the finale into a battle film, but by stripping the experience of an emotional center that would give the series a meaningful climax. Reeves and Carrie-Ann Moss barely seem present in their flat performances, as they’re given few scenes through which their bond can affect the audience, despite their love being one that’s supposed to transcend the real and virtual worlds. Superficially, the Wachowskis deliver an impressive technical package, and the effects are, of course, a pleasure to watch in a mindless kind of way. But if there’s one thing a Matrix film should not be, it’s mindless. Some fascinating scenes and ideas exist within the latter two-thirds of the Wachowskis’ cinematic world, but they negate much of what made The Matrix special with their conclusion. Perhaps it’s wrong and narrow-minded to hope that the Wachowskis would only live up to their original film, but their brand of mythology expansion narrows the possibilities and limits the viewer’s enjoyment of this universe.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review