Margin Call

By Brian Eggert |

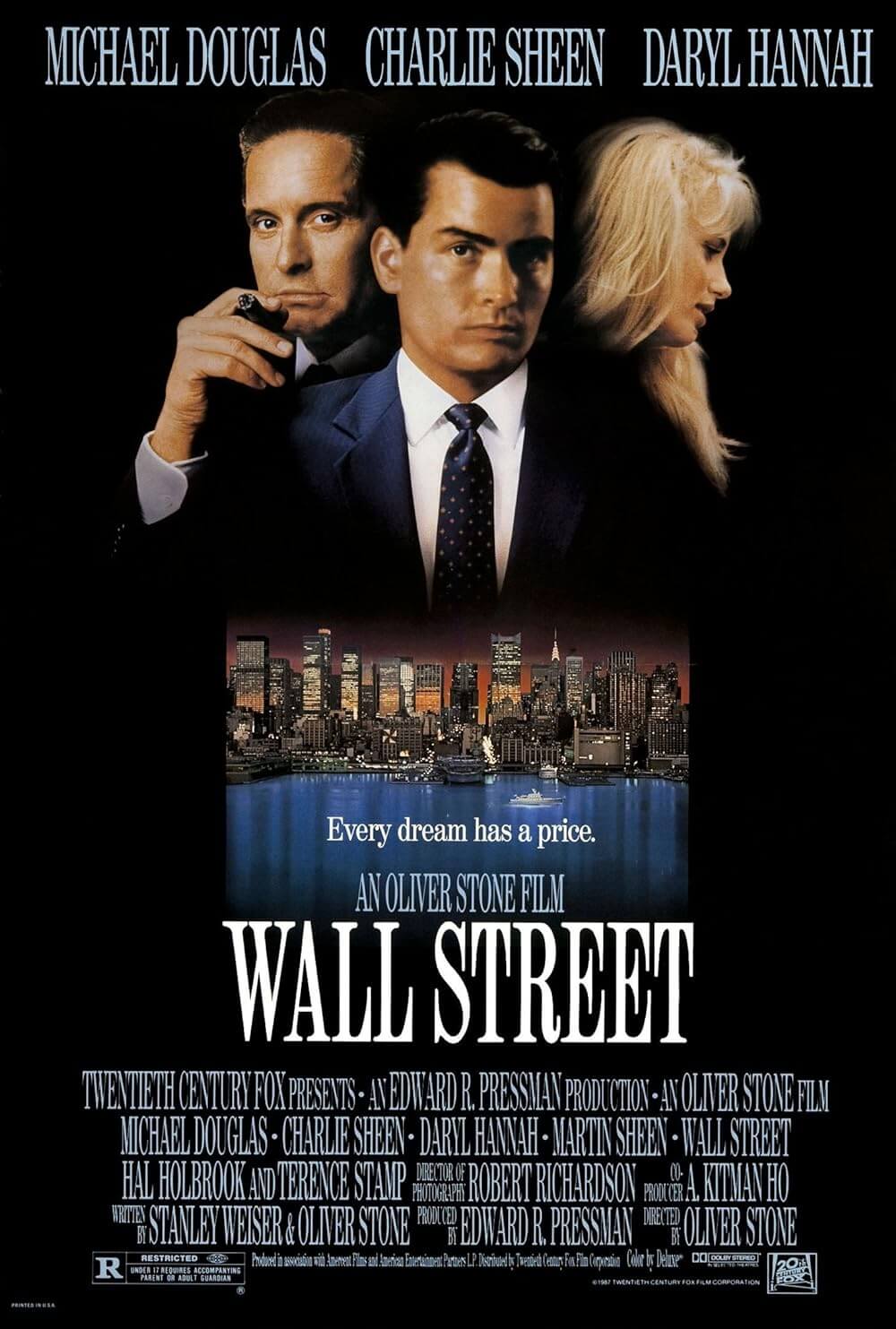

Margin Call takes place in 2008, as our economy dangles on the edge of a volcano. Written and directed by first-timer J.C. Chandor, the independently produced film does not tell a “true story” about what happened; rather, it fictionalizes a believable behind-the-scenes scenario without directly pointing fingers. The story concerns an analyst who discovers his brokerage firm’s upcoming losses go beyond their total market value. To save their butts, the company decides to unload their inventory of sub-prime mortgage holdings before their worthlessness becomes public knowledge, making a fortune as they betray their customers. Filled with convincing financial jargon delivered by the best ensemble cast you’re likely to see in 2011, the film belongs on a short list of good financial thrillers, including Oliver Stone’s Wall Street and James Foley’s film of David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross.

Referenced only as “The Firm,” the corporation at the film’s center begins its day by dropping eighty percent of its brokers in a mass layoff. The day is a stressful one, at the end of which the “survivors” celebrate. Earlier, longtime risk manager Eric Dale (Stanley Tucci) is walked out the door and, on his way, tells young analyst Peter Sullivan (Zachary Quinto) to look over his current project, and to “be careful” with what he finds. Sullivan stays late to review the numbers. When he realizes what he’s found, he calls his colleague Seth (Penn Badgley) and their boss Emerson (Paul Bettany) to look at the calculations. Before long, it’s midnight and Emerson’s boss Sam Rogers (Kevin Spacey) has been called in. Another couple of hours and Sam’s bosses (Simon Baker and Demi Moore) arrive and concur the numbers are correct. By four in the morning, CEO John Tuld (Jeremy Irons) lands on the roof via helicopter and asks Sullivan to explain what’s going on. “Speak to me as you would a child,” Tuld says, reminding audiences that executives are rarely as smart as their title suggests. And thus, finally, the audience can understand what everyone’s been talking about until now.

At this point, you’ll feel the sudden desire to purchase a Guy Fawkes mask and join those Wall Street protesters. Some consider the protesters anti-American or at least anti-Capitalism, but these days the two seem inseparable. They’re not angry about The American Way; they’re enraged by the greed fueling Wall Street, the inhumanity. This is a place where corporations service themselves for a profit, regardless of how it affects the world at large. Even in the face of disaster, Tuld (no doubt inspired by Lehman Brothers CEO Richard Fuld) thinks first about how to make as much money from what’s happening. Granted, it’s every business’ right to turn a profit, but there comes a point when your pursuit of revenue begins to destroy everything around you and, in the long term, means corporate (if not national) suicide. You’d think that with all the expensive education in attendance at these companies, someone would have been smart enough to grasp this. Alas, Gordon Gekko’s enduring motto, “Greed is good,” meant as an overstated but honest axiom in Wall Street, has been taken literally since its pronouncement, and Margin Call shows the result.

But I digress. Chandor’s onscreen assessment of these characters may feel more even-handed than one expects in troubled economic times. It’s quite realistic, thanks to the all-around strong performers who give human faces to businessmen who want nothing more than to make a buck (or a few million of them), fearing their superiors enough to suppress their reservations about company policy. Much like other financial thrillers of this sort, Chandor uses the illusory nature of money—that artificial thing that our society created to make our lives easier but instead dominates it—as an invisible device that drives all decisions. Quinto’s naïve young analyst questions whether or not his company has made the right choice, but it doesn’t matter, since the paychecks are good. Only Spacey’s 34-years-in character shows any true regret about the situation. Spacey’s character is further humanized by a subplot about his dying dog; we can’t help but feel sympathy for a man who cries at the idea of losing his best friend. Irons’ two or three scenes steal the film, however, as he’s so composed and cold; it’s his best performance in years. The cast overall is staggeringly good. Has a first-time director ever assembled such an impressive roster of talent?

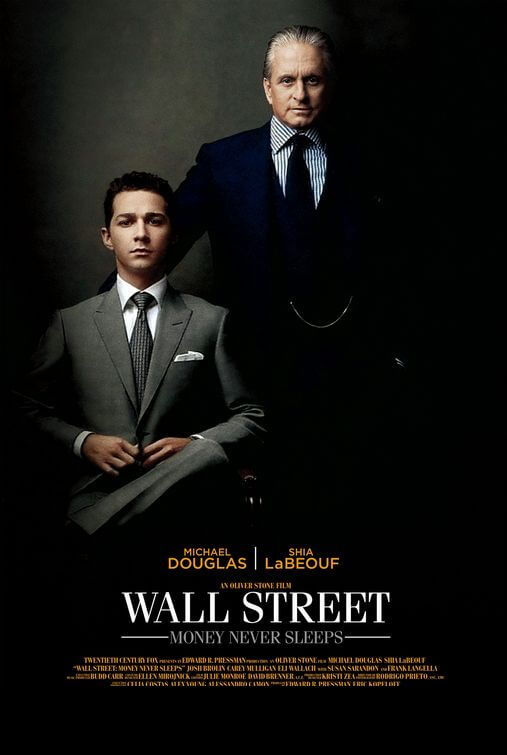

Though fuelled by compelling dialogue—in particular two monologues, a cynical one from Bettany and a chilly one from Irons—Margin Call doesn’t have a style in the language itself. It’s not a film “about” dialogue, nor is it “about” the characters, strange as that sounds. Information is presented matter-of-factly, without involving backstories to artificially enhance what’s happening. This isn’t Money Never Sleeps, where the numbers are a device propelling a melodrama. Chandor instead lays out a potboiler where things look bad, get worse, and then boil over, giving way to a poignant and somber aftermath. It’s a wonderfully acted story that puts what happened in the fall of 2008 into perspective, taking us behind corporate walls where everything hums with computer monitors and the chatter of desperate brokers, and then into board rooms where suits find themselves speechless at their company’s forecast. And afterward, we have a better understanding of the apathy that permeated our economy’s ongoing crisis, which, depending on your outlook, either focuses or alleviates your anger over the situation.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review