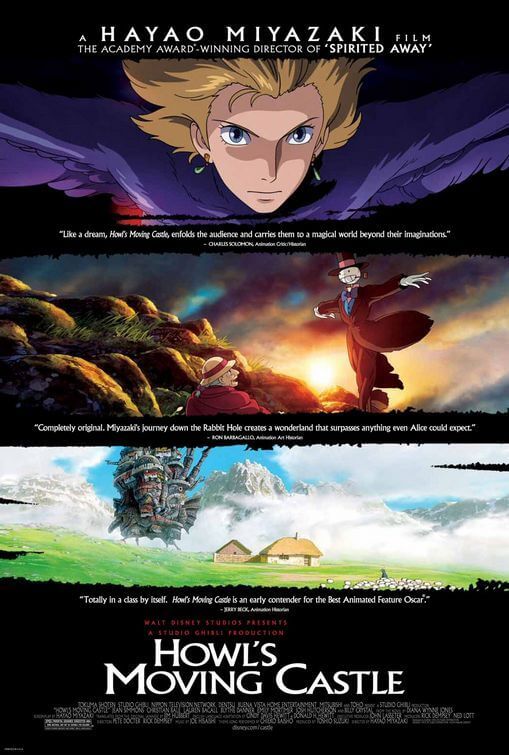

Howl’s Moving Castle

By Brian Eggert |

Based on the 1986 fantasy book by British author Diana Wynne Jones, Howl’s Moving Castle was adapted by director Hayao Miyazaki in 2004. However divergent and unfaithful an adaptation, Miyazaki brings his own sense of magic to this tale of destiny and wizard curses, underscoring the story with his own recurrent themes and imagery. And yet, amid the Japanese director’s treatment of the material and his pronounced ability to make the story feel like his own, the advanced animation style used on the picture may spoil the experience for purists. A combination of hand-drawn animation and Miyazaki’s most obvious use of computers appears onscreen, dispelling some of the film’s magic through the excessive presence of the medium’s needless modernization.

A long-time admirer of Wynn Jones and her novels, Miyazaki makes a natural move by bringing her book to film, though strangely the setting and the characters’ motivations were altered in the process of adaptation. When placed beside her story, his previous work contains similar settings and plot devices, all of which are augmented through Miyazaki’s own additions to the material. In the vein of Miyazaki’s Castle in the Sky, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Porco Rosso, and others, the setting is an ambiguous European waterfront town. The villages are quaint yet rich with markets. The architecture and clothing look reminiscent of an early 1900s backdrop, and yet there exists technology in this world that is impossible today. Eerily flying overhead, warships flap their metal wings and drop bombs on the towns below. Well into a disastrous, senseless war, the entire continent faces an indefinite political threat.

A matter-of-fact truth for this world is the presence of magic—wizards and witches who are forced by contract to support their war-mongering king. The king’s metal airships spit out winged monsters, former wizards who have transformed themselves into hideous creatures and attack without cause. Protecting innocents is a rogue wizard, named Howl, who has been summoned by the king, but, as he opposes this absurd war, he refuses to show. The audience meets him when he saves a young girl, Sophie, from harm. But her contact with Howl gets the attention of The Witch of the Waste, who curses Sophie into the twisted form of an old woman. Since part of her curse is that she’s unable to talk about it, the elderly yet spirited girl opts to run away and soon finds herself working as a cleaning lady in Howl’s castle. The plot meanders around her adventures in the castle, though there’s little direct sense of purpose behind the characters, except perhaps to showcase the involved world they inhabit.

An assemblage of scrap metal and wood, pieces of homes, and forgotten debris held together by a chummy fire demon named Calcifer, Howl’s castle looks like a junkyard come alive. Mobile on skinny metal legs, the castle walks through the Waste, an expanse of foggy hills, clanking and whistling as the magician’s ramshackle jalopy. From the inside, a dial on the door allows inhabitants to step out into various worlds; Howl keeps himself hidden from danger that way. Along with the wizard’s young boy assistant, Markl, and a living scarecrow dubbed “Turnip Head”, the castle presents a ragtag home of magic types, with Sophie as their makeshift mother and caretaker. She cleans away the dust and makes the interior hospitable, and in doing so she angers the very vain Howl when she rearranges his potions, leaving his hair color dyed like a ginger.

An assemblage of scrap metal and wood, pieces of homes, and forgotten debris held together by a chummy fire demon named Calcifer, Howl’s castle looks like a junkyard come alive. Mobile on skinny metal legs, the castle walks through the Waste, an expanse of foggy hills, clanking and whistling as the magician’s ramshackle jalopy. From the inside, a dial on the door allows inhabitants to step out into various worlds; Howl keeps himself hidden from danger that way. Along with the wizard’s young boy assistant, Markl, and a living scarecrow dubbed “Turnip Head”, the castle presents a ragtag home of magic types, with Sophie as their makeshift mother and caretaker. She cleans away the dust and makes the interior hospitable, and in doing so she angers the very vain Howl when she rearranges his potions, leaving his hair color dyed like a ginger.

Howl is a superficial wizard, preoccupied with his flamboyant appearance and needless trinkets because his heart was stolen, leaving him selfish. Of course, Sophie falls in love with Howl, because that’s what young girls do with attractive wizards. Her curse leaves her unable to express her feelings, however, and she’s forced to watch helplessly as Howl slowly destroys himself to stop the king’s war. These are the plot’s basics. Where Miyazaki falls back on his own creativity are the details: the cute chicken-footed dog that follows Sophie from the king’s castle; the massive airships that haunt the skies; the way in which Howl chooses to avoid conflict not because, as Wynne Jones wrote, he is a coward, but because he doesn’t believe in encouraging the ridiculous conflict. Indeed, the bombings themselves and the scope of the war are exaggerated by Miyazaki from the text, making them more irrational and horrific. In a promotional interview for the film, Miyazaki told Newsweek that his inspiration for the excessive and violent depiction of a senseless war was inspired by the United States attacking Iraq. The director has long been an anti-war advocate, with the notion of violent takeovers frequently depicted as meaningless atrocities in his films. His heroes so often stand between two opposing sides and hope for reconciliation, representing a basis for humanist understanding amid the violence. In this case, the political details of the war are unimportant. What matters is that someone stands against it.

Miyazaki places more fingerprints into the material by altering the look of the character descriptions, such as the morbidly obese Witch of the Waste, or the humorously childlike appearance of Calcifer. The art design of the film is immaculate, from the construction of Howl’s castle to the expansive rural European landscapes. The backgrounds, like the characters, are hand-painted, filled with detail and beauty, though they’re brought together through the sometimes distracting device of computer animation. In both Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away, Miyazaki tested making the animation process a simpler and more efficient task by implementing computer animation into his more traditional hand-drawn style, resulting in a successful interweaving of approaches.

The result is not as successful in Howl’s Moving Castle. Consider the animation of Howl’s living fortress, which moves as though Miyazaki’s style of art was combined with Terry Gilliam’s moving cutout animations from Monty Python. Instead of organic movement, we see a combination of still images being manipulated through computer technology. The more detailed the background or complicated the movement, the more obvious the reliance on computer animation becomes. The effect makes the royal castle’s marble floors shine and rapid movements seem unnatural in ways that defy Miyazaki’s traditional 2-D animation style. This type of artificiality, which removes the audience from the story to examine the effect, has a distracting presence in the Miyazaki oeuvre, the same way that CGI or 3-D would distract in an Orson Welles film. It remains the most common criticism of the film, the backlash against which may have inspired the director to return to a more obviously hand-drawn style on his next picture, Ponyo.

The result is not as successful in Howl’s Moving Castle. Consider the animation of Howl’s living fortress, which moves as though Miyazaki’s style of art was combined with Terry Gilliam’s moving cutout animations from Monty Python. Instead of organic movement, we see a combination of still images being manipulated through computer technology. The more detailed the background or complicated the movement, the more obvious the reliance on computer animation becomes. The effect makes the royal castle’s marble floors shine and rapid movements seem unnatural in ways that defy Miyazaki’s traditional 2-D animation style. This type of artificiality, which removes the audience from the story to examine the effect, has a distracting presence in the Miyazaki oeuvre, the same way that CGI or 3-D would distract in an Orson Welles film. It remains the most common criticism of the film, the backlash against which may have inspired the director to return to a more obviously hand-drawn style on his next picture, Ponyo.

The greatest appeal of any Miyazaki film dwells in its naturalism and the glorious sense that it offers an original world. For the first time in the director’s career, with Howl’s Moving Castle the audience is removed from that original world because of the animation’s unnatural appearance. And yet, the director’s talents as a storyteller are well intact. Those ever-present Miyazaki themes of destiny, pacifism, and true love saving the day are still present, and the characters are charming and the setting dynamic. In truth, the problems with computer animation only occur here and there. But that they exist at all, that we’re distracted by the artificiality of Miyazaki’s presentation even for a moment, stands as a disappointing first for this filmmaker.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review