Hedda

By Brian Eggert |

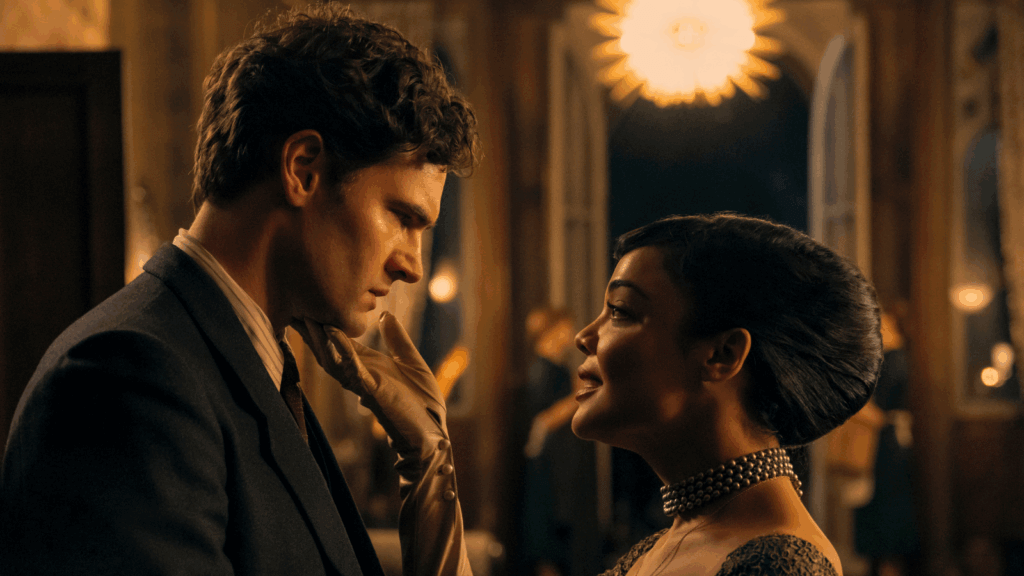

“The best time to leave a party is after something terrible happens but before the police come,” quips Hedda, a bored, married socialite played by Tessa Thompson. Ironically, the first scene in Hedda finds the titular character being questioned about what happened at a party she hosted alongside her husband, George (Tom Bateman), a distracted academic. Someone was shot, and the authorities want answers. What unfolds is an evening of drinking, ill-advised flirtations, intricate personal histories, and emotional fallout—many of them masterminded by Hedda, who yearns to wield some measure of control over her life and delights in manipulating those around her to achieve those ends. Aside from an uneven, mannered, and exaggerated English accent, Thompson does well in this role, which has been previously played by Ingrid Bergman, Diana Rigg, and Glenda Jackson onscreen. However, some of the film’s more brash stylistic choices feel like they’re unnecessarily trying to overcompensate for dialogue-driven material.

Written and directed by Nia DaCosta, this new adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s 1891 play Hedda Gabler marks her third collaboration with Thompson, after her rural noir debut Little Woods (2019) and fine-but-forgettable MCU venture with The Marvels (2023). DaCosta’s version rethinks the play from the perspective of a bisexual woman of color in twentieth-century England, where society prevents her from living freely outside of the boundaries it sets on her gender, race, and sexuality. Whereas Ibsen primarily concerned himself with the limitations put on women a hundred years earlier, DaCosta shows that time hasn’t changed things all that much. It’s easy to admire this lovely production; however, some of DaCosta’s choices prove unsubtle, suggesting she didn’t trust that Ibsen’s scenario alone could grab the audience. For instance, she adds double entendres to juice things up: When George remarks at dinner that he conducted research during their six-month honeymoon, apart from eating out at nice restaurants, a friend remarks that Hedda does “love to eat out.”

Hedda, an insatiable aristocrat who yearns to have everyone wrapped around her finger, despite having little power at her disposal, organizes a party she and George cannot afford, hoping the evening will land him a professorship to resolve their financial troubles. “Nothing can go wrong tonight, Hedda,” George explains. “Oh, and keep those guns out of sight.” Hedda has a penchant for guns, and sure enough, Chekhov’s gun reappears later in the proceedings. But until then, it’s a vaguely upstairs-downstairs affair inside an enormous estate, with more attention paid to the posh guests than the full staff of cooks and servants—save for a few choice lines from Kathryn Hunter, playing the main servant. Hedda oversees every detail, from the tablecloths to the flowers. And once their guests begin to arrive, it’s evident that she has a complicated history with most of them. She’s flirty and mischievous with almost everyone she encounters, offering desirous glances exchanged across drawing rooms and reflected in mirrors.

While George concerns himself with impressing Professor Greenwood (Finbar Lynch) and his much younger wife Tabitha (Mirren Mack), Hedda’s attention remains on her friends and long list of former lovers. Chief among them is Eileen Lovborg (Nina Hoss, playing a gender-swapped role), a newly sober academic and Hedda’s ex-lover, whose presence draws Hedda near in a double dolly shot straight out of a Spike Lee joint. Eileen’s lover and collaborator, Thea (Imogen Poots), arrives as well, having done much to get her sober. Hedda went to school with Thea and bullied her, and she intends to unravel any progress Thea made in helping Eileen for reasons that become clear later. At the same time, another of Hedda’s former lovers, a judge, Roland Brack (Nicholas Pinnock), schemes to take her for himself, drawn to her irresistible blend of sexuality and danger.

In many ways, Hedda is DaCosta’s most formally accomplished work to date, next to her Candyman remake from 2021. It’s filled with luxuriant details compiled by production designer Cara Brower’s team and stunning costume designs by Lindsay Pugh. Cinematographer Sean Bobbitt employs long, elaborate takes of this sumptuous home, lit in amber hues, to create an ornamented presentation worthy of Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993). But Hildur Guðnadóttir’s distracting, jazzy score—comparable to the one in Birdman (2014) for its propulsiveness—represents an overstylized flourish. It’s as though DaCosta doesn’t trust the material, or worse, her audience’s ability to connect with the drama, so she relies on visual or aural punctuation. Most distracting are the breathy vocalizations in the music, reminiscent of the score in last year’s Babygirl and many other films of late, that articulate how tense Hedda remains beneath the surface throughout the evening.

The film can feel like a whirlwind, racing from one moment to the next with little spatial awareness of the estate or the evening’s program. “Sometimes I can’t help myself,” admits Hedda. “I just do things on a whim. I don’t know why.” DaCosta’s approach can feel like that too, with swing-dancing interludes to “It’s Oh So Quiet” and illicit lovers sneaking off into the hedge maze to make love, only to be discovered. But Hedda’s best moments spring from quiet drama, such as an exchange between Thompson and Hoss where both speak honestly, soberly, and without that oppressive score. DaCosta is more interested in how she has changed Ibsen to fit her needs than in the roots of the play. Of course, Hedda is supposed to be a challenge to understand and resistant to all manner of labels, which should draw the viewer into her world with a pressing desire to learn more. Instead, the film feels less contingent on the emotions driving the story than the director pushing it forward with overt stylization.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review