28 Years Later: The Bone Temple

By Brian Eggert |

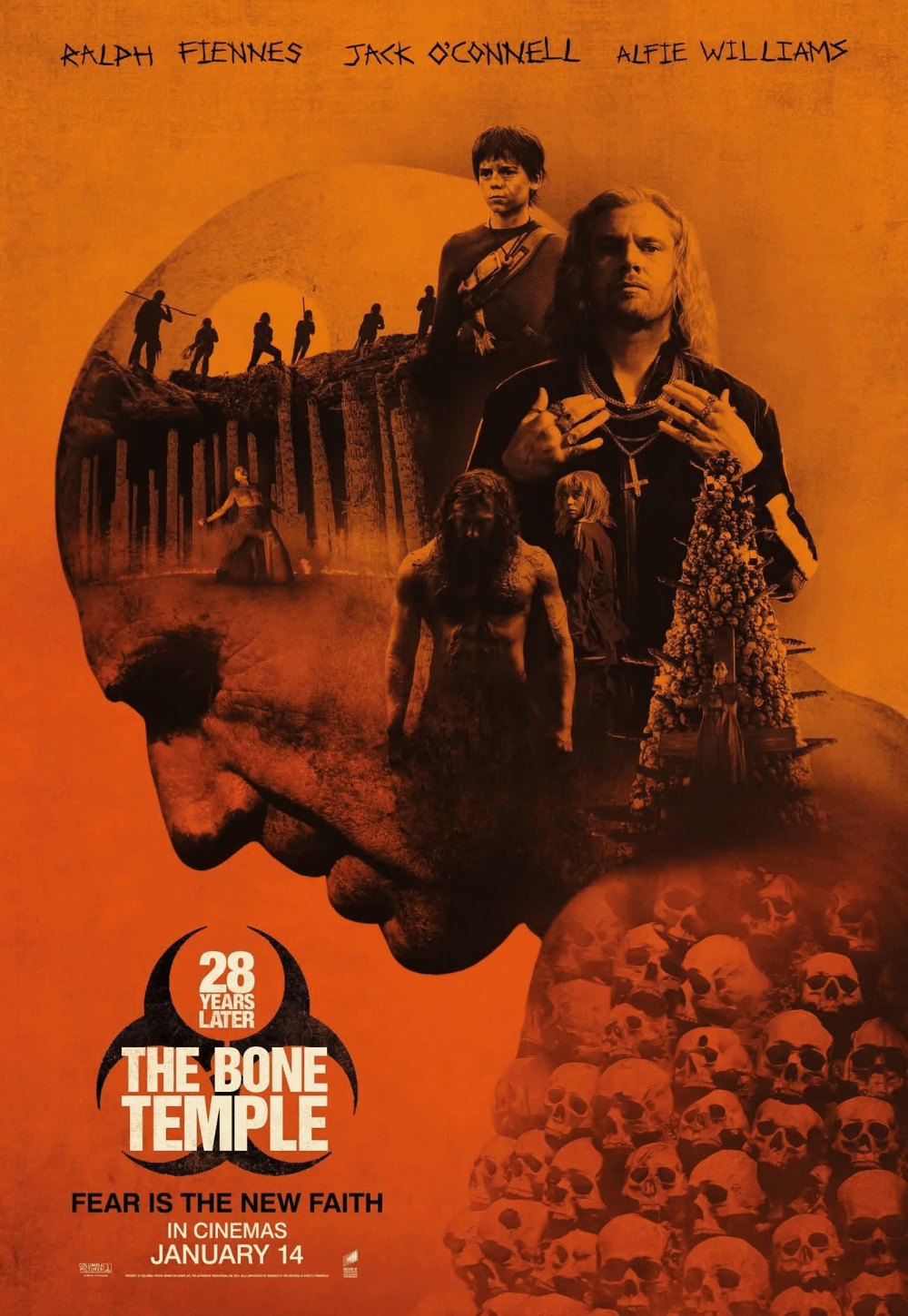

A scene in 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple finds Dr. Ian Kelson, superbly played by Ralph Fiennes, speaking about the world before the rage virus turned the UK into a post-apocalyptic nightmare. His memories have become foggy, but he recalls that the world had an order: “Its foundations unshakable.” That’s not the case anymore, neither in the film’s fictional hellscape nor in the real world. Kelson has spent over twenty years building a shrine to yesteryear in the English countryside, collecting the bones of humans and the infected for a vast memento mori of the fallen. It’s his way of remembering the departed and mourning the civilization of the past, when the world made sense. In the sociopolitical chaos of today, Kelson’s dark sentiments resonate with equal parts loss and curiosity—a yearning to understand where humanity came from, how it has descended into fanatical ideologies, and what it takes to change for the better. His approach isn’t to answer rage with rage—to wipe out the infected or even the bloodthirsty human gangs that roam the UK’s ruined landscape—but to understand the condition as a scientist and find a way of cutting through that extremism.

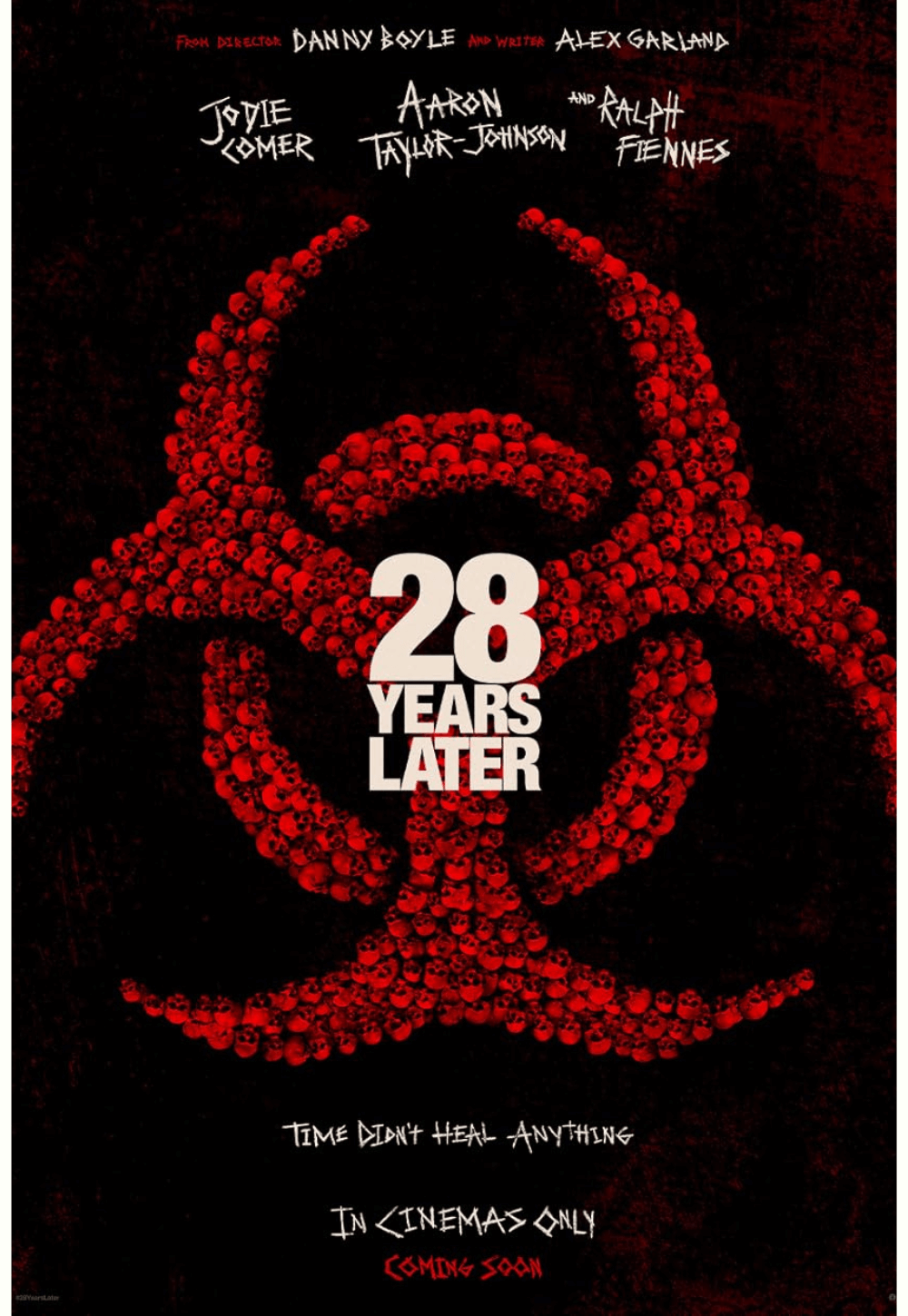

Screenwriter Alex Garland continues his meditation on humanity’s decline in this sequel to 28 Years Later (2025), which marked director Danny Boyle’s return to the series he started with Garland in 2002 with 28 Days Later. After last year’s tonally wild ride, the sequel, the second in a proposed trilogy set in the same timeframe, comes from director Nia DaCosta (Candyman, 2021). Although DaCosta’s style is more straightforward than Boyle’s signature kineticism, her regular cinematographer Sean Bobbitt employs enough disorienting camera techniques—body-mounted cameras, shaky-cam, etc.—that her film feels aligned with the earlier installments yet remains distinctive. The story in The Bone Temple, too, has fewer shifts in mood than its predecessor, which, depending on how you felt about 28 Years Later, could register as praise or a critique. But let’s consider this a mere observation of how DaCosta approaches Garland’s comparatively less turbulent material.

The previous entry leapt from Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s masculine father to his more sympathetic son, Spike (Alfie Williams), whose mission to save his sickly mother (Jodie Comer) ended in a soulful acceptance of death as a natural part of existence. It was part zombie action movie, part coming-of-age story, and part commentary on today’s cultural fragmentation. Following a long absence in the franchise since 2007’s 28 Weeks Later, it established a world where human groups have formed around hypermasculinity and religious extremism, while the infected, a culture thriving on rage, have evolved a social hierarchy. Boyle gave each of those divisions a distinct tonality in his filmmaking, and he bookended the film with a teaser of things to come—announced by a group of zippy, Teletubby wannabes donning multicolored track suits and mopish blonde wigs, led by Jack O’Connell’s charismatic but dangerous ringleader of his so-called “Fingers.”

DaCosta tells a story less dependent on mood fluctuations than Boyle’s. Picking up immediately after the events in 28 Years Later, Garland’s screenplay opens with Spike in the company of the “Jimmys.” Eight in all, they’re led by O’Connell’s self-described Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal, who also names his acolytes Jimmy, save for one of the two women in his posse, whom he calls Jimmima. It’s no arbitrary choice that they wear bleach-blonde wigs and repeat their leader’s refrain, “How’s that?” Their appearance and behavior, including a predatory tendency to ravage anyone they come in contact with, were based on Jimmy Savile. For the uninitiated, consider yourself lucky. Savile was a knighted oddball media personality and host of two BBC television shows, known widely throughout the UK. But after he died in 2011, an unthinkable number of people came forward to expose Savile as a pedophile with upwards of 300 victims; his alleged crimes even extended to necrophilia. Savile’s catchphrase—“How’s about that, then?”—was also the name of his biography. So the Jimmys’ extratextual creep factor is considerable. At the outset, their leader forces Spike into a fight to the death to prove his worth. Out of sheer luck, Spike survives, making him the latest Jimmy to join the fold.

Not far away, Kelson, who has discovered that covering his skin with iodine fights the rage virus, continues to collect the bodies of the fallen, clean them of their flesh, and add their bones to his ossuary. He also receives regular visits from Samson (Chi Lewis-Parry), the towering infected from the last film, who is stronger and more intelligent than the others. Curiously, Samson keeps returning to Kelson, as though welcoming the doctor’s neutralizing morphine blow-darts. Kelson believes Samson wants “peace and respite,” and perhaps he does too. One day, while Samson sits in an opium-induced daze, Kelson takes morphine and sleeps next to the giant, gambling with his life. After all, when Samson comes to, he might have ripped Kelson’s head and spinal column from his torso, as he tends to do. Instead, he leaves Kelson in peace, only to return for another dose. What develops is an unlikely bond between the two, with the good doctor attempting to treat the rage virus like a form of psychosis.

Inevitably, these two storylines collide. Erin Kellyman plays one of the Jimmys sympathetic to Spike, recognizing that he will never adopt their routine of trapping fellow human beings and sacrificing them—in a particularly gruesome way—to their god, Old Nick (aka Satan). She eventually alerts Jimmy Crystal to Kelson’s presence and describes him as Old Nick, complete with reddish skin and, from an outsider’s perspective, a hellish sepulchral compound. It quickly becomes apparent that their warped leader has brainwashed them with his half-delusion, half-consciously manipulative theology, and what’s more, he’s wary of being exposed. Kelson is quick to size up the situation, and, as with the rage virus, he looks for a logical solution. The climactic scene—where Kelson dances to Iron Maiden’s “The Number of the Beast” in a wild, performative deception—challenges Fiennes’ dance in A Bigger Splash (2015) for one of the actor’s most joyous and instantly iconic moments onscreen.

To be sure, Fiennes’ character grows beyond his limited screen time in last year’s 28 Years Later, adding a sense of loneliness and sly rebelliousness to the character. He’s the heart and mind of the film. Just look at his collection of vinyl or the photos on his bunker wall, and it’s apparent this is a multifaceted character the film just begins to explore. That said, Kelson is an atheistic, scientific mind in a world that has been overrun by unchecked negative emotion: fear, anger, hatred, delusion, and belief in place of facts. He’s everything that today’s unraveling culture, especially in America, lacks, from his rationality to his willingness to meet his potential enemies on diplomatic terms. Garland seems to present Kelson as the only sane man in an insane world. Later in the film, a familiar character teaches a lesson in world history and reminds us that this series of films has existed in an alternate universe since 2002. He remarks on how, after World War II, fascism and nationalism were no longer concerns; humanity had learned its lesson. If there’s one way in which this franchise presents a preferable world, it’s how the characters never had to deal with fascism returning.

The Bone Temple is the first great movie of 2026, a rarity for January. It’s a triumph of rich thematic storytelling and social reflection that beckons its audience to search for answers and solutions rather than act on the lizard-brained instincts and emotions that fuel humanity’s worst impulses. It’s also thrilling, with its horror aimed less at the infected and more at the disturbing things humans will do to each other for arbitrary reasons. Yet, it also has unlikely humor and heart in Kelson. What’s constantly surprising is how the film, despite occupying the well-worn zombie apocalypse genre, defies formulas and expectations at almost every turn. Fortunately, Boyle and Garland have announced that a third 28 Years Later could be next, assuming Sony sees a profit from The Bone Temple. And while the ending here allows a measure of closure, so that if it ends here, it has ended well, another installment cannot come soon enough. With each entry, this series has reinvented itself, and The Bone Temple is the best since the original.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review