The Definitives

In the Mood for Love

Essay by Brian Eggert |

Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love adopts the structure of a memory, where rapturous moments overcome the traditional flow of time, preserved by desire and accessed when longing calls upon the experience. A chimeric vision set in Hong Kong during the sixties, the film entails two neighbors who realize their spouses are having an affair, and then contemplate a romance themselves. The experience is phenomenological, rooted in consciousness and quieted erotic yearning, as very little actually happens in the film beyond its repetition of familiar gestures, sensations, locations, and musical patterns—an intangible immersion into the nimbus of emotion. Wong’s lyrical imagery conjures activity in the viewer’s mind, and what the director puts before us is just as significant as what we imagine happened in omitted scenes. That the film’s would-be lovers never realize their affections, at least not in the customary manner of cinematic representation, reinforces Wong’s emphasis on minimal plotting and distortions of time in the film, which would not be too pointed to describe as a mood piece. Wong, whose work is a genre unto itself, much as Hong Kong is outward from mainland China, explores an underground of persistent desire and inhibition. And though the film bears his postmodern interest in aesthetics of time and space, leading to larger questions about the intersections and corruptions of colonialism across cultural and historical lines, there are boundless delights in Wong’s exploration of the ephemeral, desirous chambers of the mind.

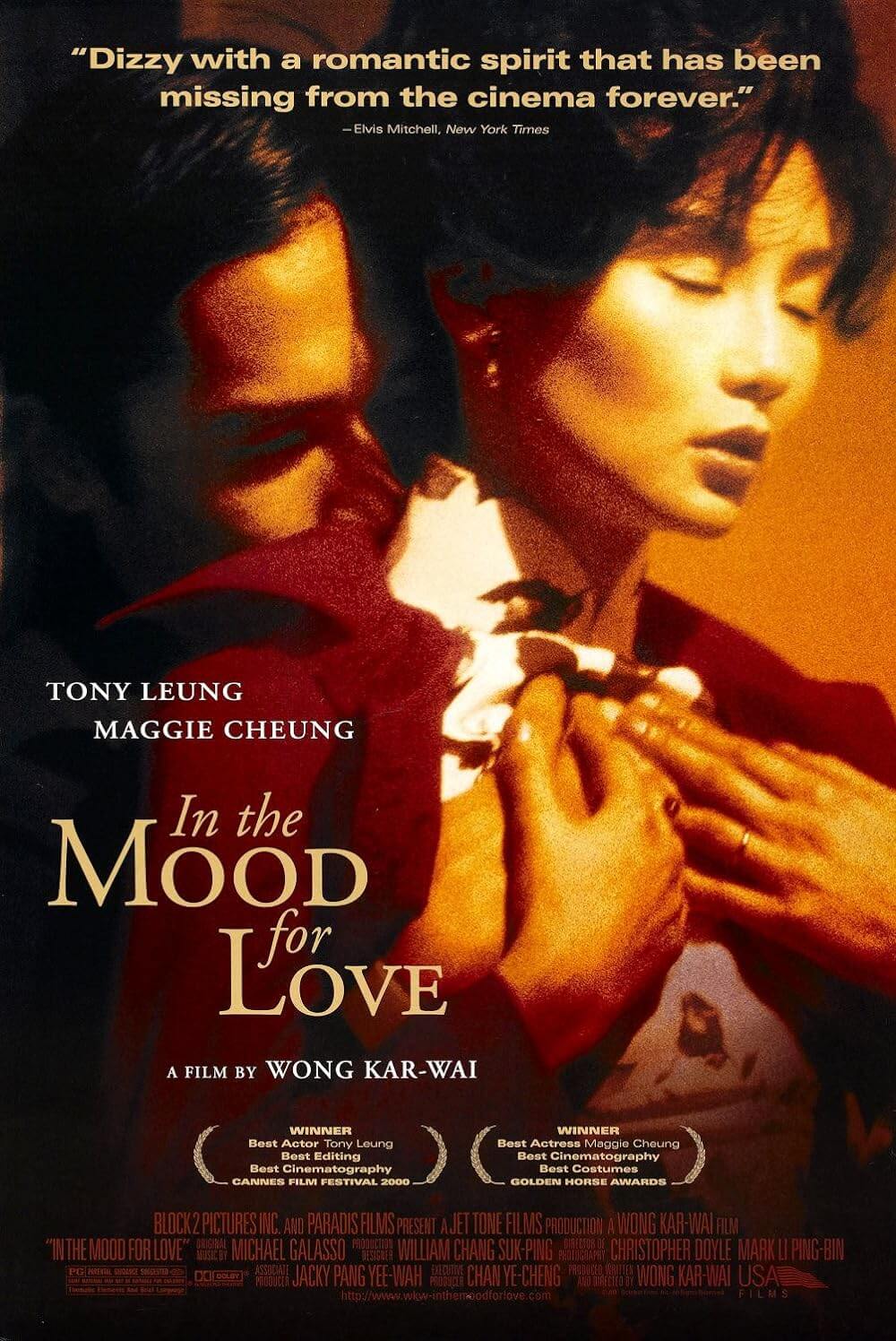

In the Mood for Love contains a depth and sophistication beyond other films, a masterful interweaving of texts, including a complex formal approach, an elusive story, historical references, and autobiographical touchpoints for its director. It demands investigation and, like the most venerable works, teases its meaning even as it invites the viewer back to obsess over its intimations and beauty. Yet, Wong often starts his productions without much more than a vague sketch of a script, using a trial-and-error technique that clashes with budgetary constraints and distributor deadlines. He took almost two years to make In the Mood for Love, completing the last edits the night before its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 2000. More than with his earlier features, such as Chungking Express (1994) and Happy Together (1997), Wong was forced to think about his use of the image while making In the Mood for Love. His previous cinematographer, Christopher Doyle, had always given him just what he wanted without the director having to ask. But Doyle had to be replaced when the production went over schedule. Mark Lee Ping-bing, known for his work with Hou Hsiao-hsien and Tran Anh-hung, took over for Doyle and created an alternative aesthetic to Wong’s earlier films. Whereas before his work could be described as kinetic and even discordant, In the Mood for Love bears the organized structure of a song or poem. How unlikely that the actual 15-month process of shooting the film involved trying things and then trying them again, much to the frustration of its stars, Maggie Cheung Man-yuk and Tony Leung Chiu-wai.

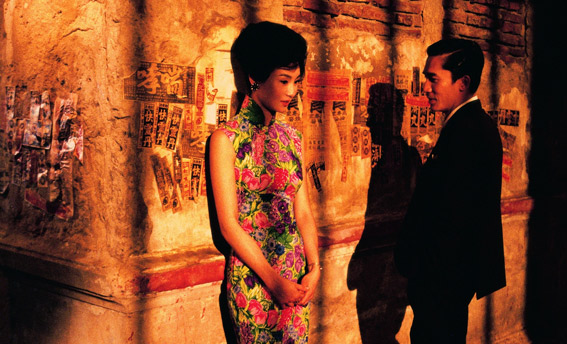

But Wong’s process, and the degree to which In the Mood for Love presents an aesthetic departure for the filmmaker, proves less compelling than the divinely arranged and considered result. Moreover, there’s only trivial value in the connections amid the earlier Days of Being Wild (1990) and the later 2046 (2004), which suggest a tenuous trilogy, perhaps even an extended Wong-verse, in which characters of the same name inform their behaviors from other films. Such vague implications diminish the singular movements, textures, and replays that emerge through In the Mood for Love’s constant negotiation of personal and historical consequence, where cultural gestures are inextricable from their emotional core. More than Wong’s other works, the film recalls Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993) in their meditation on time, longing, sensation, and repression. Each of these films explores an almost imperceptible blossoming of suppressed emotion, while at the same time, each applies sumptuous colors that contrast the hidden feelings of its characters. Wong takes his approach further by ensnaring his characters’ romantic appetites within symbolically cramped interiors, tight hallways, and narrow stairways—even outside, characters are trapped by the rain or framed behind bars in an alleyway, figuratively imprisoned—to reflect the internalization of desire.

No plot summary of In the Mood for Love could adequately capture the information withheld by Wong, as he communicates in subtle motions and impressions that must be observed and interpreted. At its core, the film explores, through a restrained and tender narrative, the subdued romance between Hong Kong newspaper journalist Chow Mo-wan (Leung) and a shipping company secretary Su Li-zhen (Cheung). Set against a period of Cold War strife unfolding in the background almost without notice, the story opens as, on the same day in 1962, Mo-wan and his wife and Li-zhen and her husband make a disorderly move into a crowded apartment building, which is owned by Mrs. Suen (Rebecca Pan). They join a neighborhood of people who have escaped Communist Shanghai for Hong Kong, though the urban sprawl of their new haven will be no less isolating. At first, Mo-wan and Li-zhen encounter each other in brief and polite exchanges—he borrows her paper, she borrows his martial arts books, they pass each other on the stairs and share a pregnant gaze—but the nature of their behavior changes when they discover that their spouses are having an affair. As their partners remain heard but unseen, either altogether absent or their faces never spied by the camera, Mo-wan and Li-zhen spend time together, dodging their mutual desire for one another out of their need to appear respectable. “We can’t be like them,” they vow, feeling pressed upon by their nosy neighbors and wounded pride.

No plot summary of In the Mood for Love could adequately capture the information withheld by Wong, as he communicates in subtle motions and impressions that must be observed and interpreted. At its core, the film explores, through a restrained and tender narrative, the subdued romance between Hong Kong newspaper journalist Chow Mo-wan (Leung) and a shipping company secretary Su Li-zhen (Cheung). Set against a period of Cold War strife unfolding in the background almost without notice, the story opens as, on the same day in 1962, Mo-wan and his wife and Li-zhen and her husband make a disorderly move into a crowded apartment building, which is owned by Mrs. Suen (Rebecca Pan). They join a neighborhood of people who have escaped Communist Shanghai for Hong Kong, though the urban sprawl of their new haven will be no less isolating. At first, Mo-wan and Li-zhen encounter each other in brief and polite exchanges—he borrows her paper, she borrows his martial arts books, they pass each other on the stairs and share a pregnant gaze—but the nature of their behavior changes when they discover that their spouses are having an affair. As their partners remain heard but unseen, either altogether absent or their faces never spied by the camera, Mo-wan and Li-zhen spend time together, dodging their mutual desire for one another out of their need to appear respectable. “We can’t be like them,” they vow, feeling pressed upon by their nosy neighbors and wounded pride.

As Jacqui Sadashige observes in The American Historical Review, Mo-wan and Li-zhen’s dance around their love mirrors how many world powers, from the British empire to China, maneuvered around Hong Kong, a colonized region where both the Eastern and Western influences were unmistakable. Wong’s family was among the emigrants who fled communist-controlled Shanghai for the relative freedoms of Hong Kong, a move that occurred when he was just five. He told The New York Times, “We were always prepared, as kids, that we would move on, to someplace else or back to Shanghai. There was no sense that you belonged to this place or city.” The exodus from Shanghai to Hong Kong mirrored the trajectory of Hong Kong cinema, whose roots in Shanghai were disordered and broadened after the Japanese captured the city in 1937 and the Chinese revolution of 1949, resulting in separate Cantonese and Mandarin industries in the territory. Scholar David Bordwell argues in favor of the rich postmodern tradition of Hong Kong cinema, most of which involves martial arts and thrilling gunplay, suggesting that Wong is characteristic of Hong Kong cinema in that he recycles visual and genre-based motifs to achieve something familiar albeit unique. However, Wong’s approach rarely falls into the category of the genre films with which Hong Kong cinema is most often associated—works by Jackie Chan, Johnnie To, or Stephen Chow. Instead, Wong combines Hong Kong sensibilities with the European arthouse aesthetic of Robert Bresson and Michelangelo Antonioni.

The tentative nature of Hong Kong created a lasting sense of detachment, a failed commitment and temporariness that Wong instills in Mo-wan and Li-zhen. The untried lovers never feel like they belong to each other; there’s no sense of permanence or finality between them, just a feeling that their stations are provisional. As Mo-wan and Li-zhen’s hesitant romance could be seen as a metaphor for the impermanence and displacement of Hong Kong identity, Wong avoids narrative certainties. In the Mood for Love is a film of secrets and self-deceptions, not only the spouses’ affair in their so-called business trips to Japan but in the way the abandoned Mo-wan and Li-zhen react. They are drawn together by a shared secret that they cannot discuss with anyone else, which they must protect to preserve their pride and respectability, yet they struggle to conquer their reticence. Mo-wan resolves to occupy his time as a writer of wuxia books, as many Shanghai émigrés did, and he rents another room, numbered 2046, under the pretense of writing space to complete his martial arts story. Li-zhen agrees to help him write the book, but their close proximity to one another heightens their moral pressure. Mo-wan’s more voracious colleague and friend, Ping (Siu Ping-lam), admonishes him for his cloistered behavior: “I don’t have secrets like you, I just go get laid.” But even in a sequence when Li-zhen finds herself trapped in Mo-wan’s room overnight for fear of being discovered by Mrs. Suen, they do not act, not even the temptation of a kiss. Instead, their relationship consists of hypothetical fantasies and conversations about their spouse’s tastes in food; when they dine together at a restaurant, they order what their spouses would order. Rather than break down their inhibitions toward one another, they ask questions such as “What are they doing now?” They also act-out painful little scenes that suppose how their spouses met or who made the first move.

Wong finds a dramatic undercurrent in these skits, implanting every gesture of their play-acting with a double-meaning; as their performances cast their spouses into imagined roles, they could also stand for their own affair. What’s more, Wong does not announce their performances, he drops the viewer into a scene where Mo-wan seems to seduce Li-zhen, except he’s pretending to be her husband seducing his wife. Later, Li-zhen seems to be confronting her husband about his affair in an excruciating scene (“Do you have a mistress?”), and Wong allows the scene to carry on, until he reveals it is Mo-wan acting as her husband in another rehearsal. “I didn’t know it would hurt so much,” she confesses afterward. Despite the performative quality of their relationship, their actual feelings for one another emerge through these rehearsals, through their role-playing, making it impossible to distinguish between the real and the performed. Then again, perhaps this is the point Wong hopes to make—that relationships, to some extent, consist of two partners committing themselves to prescribed roles out of social obligation. Even so, the real-life impact of their play-acting cannot be denied. Mo-wan admits, “I was only curious to know how it started, and now I know. Feelings can creep up just like that.”

Straightforward as these proceedings may seem by their description, In the Mood for Love unfolds in elliptical form, caught within the vague temporal and memory space of Mo-wan and Li-zhen’s encounters. There are no establishing shots that sweep across Hong Kong, just a series of cramped interior spaces and claustrophobic exteriors. Outside, Mo-wan and Li-zhen find themselves caught in the rain, passing by each other to buy food from the same vendor, or exploring empty city streets that nonetheless feel restricted. There are no vivid street scenes of the highly populated neighborhood, and rarely do we see superfluous characters or extras filling the frame. Shots of Li-zhen at work feature only her boss; Mo-wan’s scenes at work seem to take place when nobody else is around, except for Ping. Wong intended his film to function as a recollection, with scenes that enhance the connection between Mo-wan and Li-zhen from their focus on one another. There are no reverse shots nor cameras peering over the shoulder in conversations, just stationary images and a straightforward, often symmetrical perspective held for an immersive intimacy, as if we experience their scenes together first-hand. Critic Tony Rayns compares the approach to Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), a film that is set almost entirely on the faces of those involved. Wong’s unconventional chronology is further indicated by Cheung’s cheong-sam wardrobe, where the attentive viewer will notice that, despite the same form-fitting, high-necked dresses worn throughout the story, the patterns sometimes change within a scene, suggesting that such encounters occurred repeatedly and blended together in Mo-wan and Li-zhen’s memories.

Wong’s concentration on memory builds what French theorist Gilles Deleuze called “crystal-images” that evoke an imagined past through the actual present, until the two periods are indistinguishable, creating a vague impression of the “transcendental form of time.” The key to this approach is Wong’s subjective frame, which eschews objectivity to tell a story that exists outside of the screen and in some combination of Mo-wan and Li-zhen’s memories. He uses mental images that go beyond the documentation of a story with a camera and instill a more abundant experience. Deleuze, too, believes that the structure of cinematic narratives no longer depends on what appears onscreen, that films were actually enhanced as directors such as Bresson, Antonioni, and Andrei Tarkovsky—all influences on Wong—explored the subjective camera and crystal-images. These filmmakers, and Wong, argues scholar Flannery Wilson, represent “a certain type of cinema, one that is powerful enough to shock the film viewer out of a lazy state of mind and toward a world in which human movement does not always map directly onto time.” Watching In the Mood for Love, it becomes apparent that the audience remains unsure about whether the events before us happen in real-time or in a memory. In effect, the film moves away from the image proper and into a realm where the image is something far more ambiguous and suggestive: a subjective perception of enigmatic time and space—a memory.

Wong gives these delicate and uncertain recollections structure not through temporal linearity but through his repetition of visual and aural motifs, which act as a conglomeration of experiences and emotions that have formed into an elegy. He considers and reconsiders the same angles, the same hallways, the same stairways, the same clock, and the same colors. Most pronounced among the film’s rhythms are the musical interludes, above all the valse triste called “Yumeji’s Theme,” written by Japanese composer Shigeru Umebayashi for the final entry in Seijun Suzuki’s Taisho Trilogy, called Yumeji (1991). Wong’s use of “Yumeji’s Theme” is often accompanied by slow-motion actions to highlight the mood of this sad waltz film. In place of ambient sound, Michael Galasso plucks strings in a woefully romantic score that not only works in unison with the film’s patterned structure and memory images, but it emphasizes them and, as critic and historian Peter Brunette writes, “actually ‘activates’ much of what is visually brilliant in them.” Along with “Yumeji’s Theme,” Wong also uses Nat King Cole’s version of the Spanish song “Quizàs, Quizàs, Quizàs,” whose translated lyrical refrain of “perhaps” offers a more literal take on the vacillation between Mo-wan and Li-zhen. Wong uses the music to conjure images of the two dancing in the viewer’s mind, and he extends the concept of “perhaps” to the unseen and imagined, leaving the audience to consider what the leads might do together when they meet off-screen.

Wong gives these delicate and uncertain recollections structure not through temporal linearity but through his repetition of visual and aural motifs, which act as a conglomeration of experiences and emotions that have formed into an elegy. He considers and reconsiders the same angles, the same hallways, the same stairways, the same clock, and the same colors. Most pronounced among the film’s rhythms are the musical interludes, above all the valse triste called “Yumeji’s Theme,” written by Japanese composer Shigeru Umebayashi for the final entry in Seijun Suzuki’s Taisho Trilogy, called Yumeji (1991). Wong’s use of “Yumeji’s Theme” is often accompanied by slow-motion actions to highlight the mood of this sad waltz film. In place of ambient sound, Michael Galasso plucks strings in a woefully romantic score that not only works in unison with the film’s patterned structure and memory images, but it emphasizes them and, as critic and historian Peter Brunette writes, “actually ‘activates’ much of what is visually brilliant in them.” Along with “Yumeji’s Theme,” Wong also uses Nat King Cole’s version of the Spanish song “Quizàs, Quizàs, Quizàs,” whose translated lyrical refrain of “perhaps” offers a more literal take on the vacillation between Mo-wan and Li-zhen. Wong uses the music to conjure images of the two dancing in the viewer’s mind, and he extends the concept of “perhaps” to the unseen and imagined, leaving the audience to consider what the leads might do together when they meet off-screen.

Wong has stated in interviews that he intended the audience’s perspective to be that of a neighbor, always obscured or peering out from the door frame, never with a full view of the interior scenes. This notion contrasts what critics and scholars have observed as Wong’s subjective camera, his film’s immersion into fleeting images from Mo-wan and Li-zhen’s memories. In the Mood for Love seems to operate on both levels at once—both within and outside of a subjective perspective that avoids tying images together in an orderly fashion, just as our distant memories might materialize in our minds like cinema, not with the coherence of time but their emotional significance. As a result, the viewer’s imagination must interpret and make connections between what is outside of the frame’s boundaries, like an astrophysicist who knows black matter is there but cannot see it. Wong hints at this very idea when Li-zhen remarks on her boss’ new tie, and he is surprised that she noticed. “You notice things if you pay attention,” she remarks. It’s a statement that refers to the literal tie, but also the state of affairs of Mo-wan, Li-zhen, and their spouses. The notion can be applied to the entire experience of watching In the Mood for Love, as Wong demands that his audience interpret characters and situations that do not express themselves through exposition but through body language and film form. Wong’s approach in this regard is unquestionably postmodern in how he liberates the viewer from traditional cinematic comprehensions.

With the film situated in memories, Wong develops an interiority to his style, where everything onscreen—at least until the final coda—seems to come from within his characters, specifically Mo-wan. In an interview for City Entertainment magazine, translated by Rayns, Wong described his characters as having “closed off lives and can’t reveal themselves; they’re afraid to get hurt.” This represents a sharp contrast to his other, more outward displays in films such as Days of Being Wild or Fallen Angels, which adopt an uninhibited expressivity. In the Mood for Love has a phantom quality, where sensations of taste, touch, and smell arrive from the experiences of Mo-wan, Li-zhen, and their surroundings. Wong’s production designer and editor William Chang selects various wallpapers and prints, color motifs, and frequent fades to black that reflect the inner lives of the characters, as if everything onscreen has been pressed through the filter of memory. It’s a filter that draws allusive connections between scenes and implies that, in-between them, there lies a secret to discover. “It’s not a case of style over substance,” writes scholar Curtis K. Tsui of the technique, “rather, it’s style as substance.” Every intangible meaning arrived at through the film’s style of reminiscence is thus intensified like details preserved in our selective memory. As the end titles read, “He remembers those vanished years. As though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.”

All at once, In the Mood for Love breaks its pattern and emerges from Mo-wan’s memory in the last few scenes, and Wong reinforces his film as a political allegory for the ever-shifting, never-materializing identity of Hong Kong. “That era is past,” titles read. “Nothing that belonged to it exists anymore.” Archival footage of Charles de Gaulle’s visit to Phnom Penh in Cambodia in 1966 breaks the rhythms of the film. The 1966 scenes unfold in a period of cultural revolution and anti-British mainland riots, when the colonization of Western powers came to an end in Southeast Asia. Mo-wan has taken a post in Singapore. The riots have compelled Mrs. Suen and the Koo family to leave their apartments. Li-zhen comes looking for him at the apartment, and Mo-wan does the same, just missing her. He eventually appears at the ruins of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the twelfth-century structure designed like a microcosm of the entire world. Where better for Mo-wan to hide a secret? Wong shoots these scenes in the opposite manner of his Hong Kong scenes, offering open spaces and capturing the full breadth of the historical site—we are no longer looking back into Mo-wan’s memories. Following a tradition, he whispers his secret, presumably about Li-zhen, into a notch and covers it with mud for all time. The Buddhist temple could stand as the love affair that never was, now in shambles; it’s also a symbol of historical permanence, whereas untold histories, transitions of power, and fleeting romances remain forgotten to time. After all, Wong has tied his romance on a historical frame, from Angkor Wat to room 2046, which references the fifty-year deadline—as promised by Deng Xiaoping before his death—on which Hong Kong would earn its sovereignty after it became a region of China in 1997.

Rayns describes Wong’s political context as “a requiem for the end of the colonial period,” as Mo-wan and Li-zhen’s relationship mourns the brief pairing of two cultures, for better or worse. But their would-be romance may not have been unproductive, as hinted by the film’s suggestions that they slept together off-screen. Note the line “I don’t want to go home tonight” when they embrace in a taxi, which marks the only break in their inhibitions. Or what about the scenes set in 1962, in Mo-wan’s Singapore hotel room, where Li-zhen appears without a wedding ring, steals his slippers as a memento, and leaves her lipstick on a cigarette butt as a sign she’s been there? Later, in the 1966 scenes, Li-zhen appears with a child, prompting questions about whether Mo-wan is the father. These scenes remain so indefinite and tenuous, it’s impossible to know. Our suspicions might be justified by the existence of a deleted scene where Mo-wan and Li-zhen sleep together, which Wong removed at the last minute, just before the film’s Cannes premiere. Knowledge of the deleted scene—available on various DVD and Blu-ray releases—betrays the enchanted secrets of In the Mood for Love. Unlike, say, a classic Hollywood film that fades to black when the couple closes the curtains or sets their shoes outside of the bedroom door, implying what will happen next, the viewer can only assume what occurred between Mo-wan and Li-zhen based on the text. It’s speculation about a presumption, and it’s never confirmed, except through the extra-textual existence of a deleted scene. What appears onscreen remains uncertain and filled with desire.

Through its aching lack of resolution, In the Mood for Love ruminates on history and memory, leaving unanswered questions about the documented and the experienced. Wong had never before and would never again cast such a spell of melancholy and mystery over his audience, as his subsequent films would prove disappointments by comparison, while his career has since entered a retrospective phase. In the Mood for Love has been ranked among the greatest films ever made by Sight & Sound and other film institutions. This is not surprising, as its seductive effect only grows with consideration of its intertextuality, and the process of interpretation required to assemble its full potential. The film’s web of time and place and emotion ensnares, provoking an urgent need to disentangle oneself from its sensory immersion. At the same time, this is uncommonly lavish filmmaking, with Wong’s intoxicating and hypnotic application of form, the stunningly nuanced and sad performances, and the seductiveness of the story leaving us in a state of rapture. In the Mood for Love feels like an extravagant valentine from Wong that alerts every receptor, engaging the intellectual and elemental in an experience that, not unlike the romance between Mo-wan and Li-zhen, occupies a permanent space in our memory.

Bibliography:

Arthur, Paul. Cinéaste, vol. 26, no. 3, 2001, pp. 40–41. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41689368. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Bear, Liza, and Wong Kar-wai. “Wong Kar-Wai.” BOMB, no. 75, 2001, pp. 48–52. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40426765. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Bordwell, David. Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. Harvard University Press, 2000.

Brown, Andrew M. J. “Directing Hong-Kong: the political cinema of John Woo and Wong Kar-wai”. Political Communications in Greater China: The construction and reflection of Identity. Rawnsley, Gary D. & Rawnsely, Ming Yeh T. New York: Routledge, 2003, pp. 215-235.

Brunette, Peter. Wong Kar-wai. University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986.

—. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Sadashige, Jacqui. The American Historical Review, vol. 106, no. 4, 2001, pp. 1513–1514. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2693166. Accessed 25 Feb. 2020.

Tsui, Curtis K. “Subjective Culture and History: The Ethnographic Cinema of Wong Kar-Wai.” Asian Cinema, 7.2, 1995, pp. 93-124.

Wilson, Flannery. “Viewing Sinophone Cinema Through a French Theoretical Lens: Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood For Love and 2046 and Deleuze’s Cinema.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, vol. 21, no. 1, 2009, pp. 141–173. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41491002. Accessed 24 Feb. 2020.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review